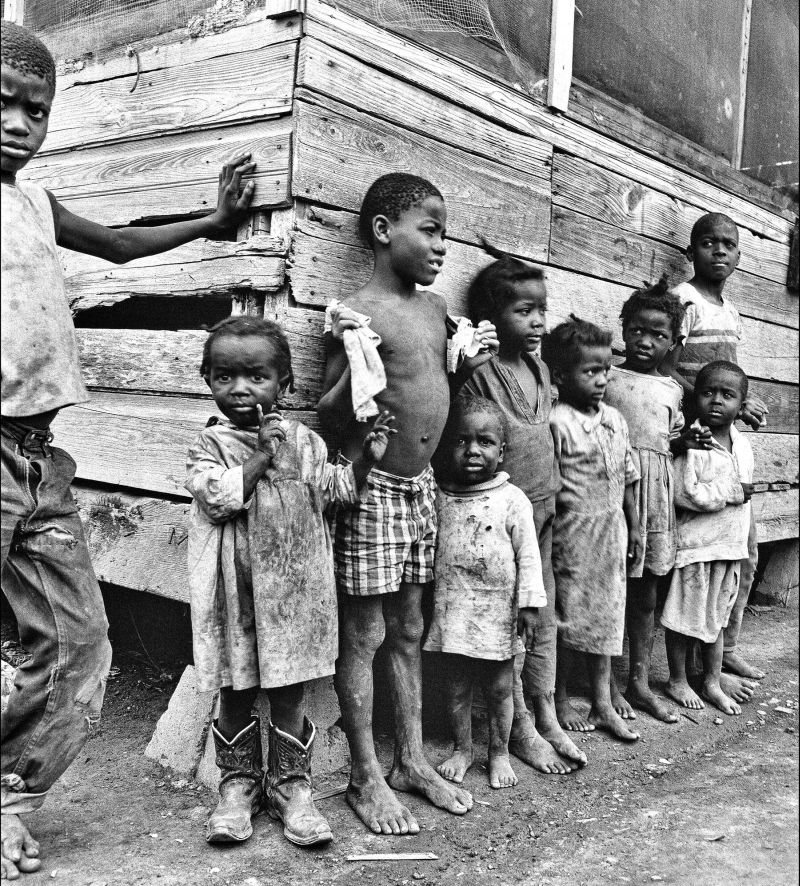

Senator Robert F. Kennedy, a son of America’s promise, power, and privilege, knelt in a crumbling shack in 1967 Mississippi, trying to coax a response from a child listless from hunger. After several minutes with little response, the senator, profoundly moved, walked out the back door to speak with reporters. He told them that America had to do better. What he was seeing, as he privately told an aide and a reporter, was worse than anything he had seen before in this country.

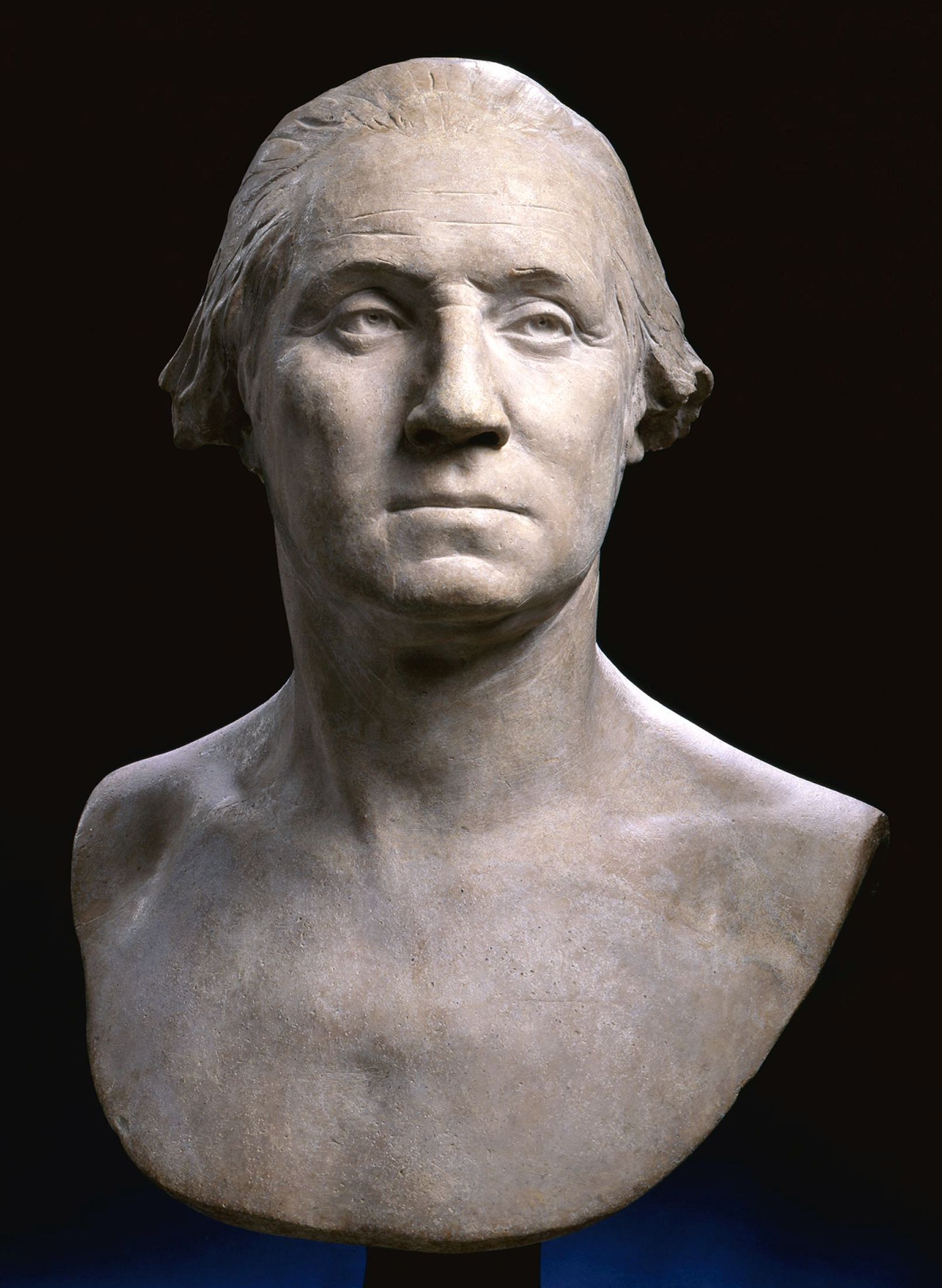

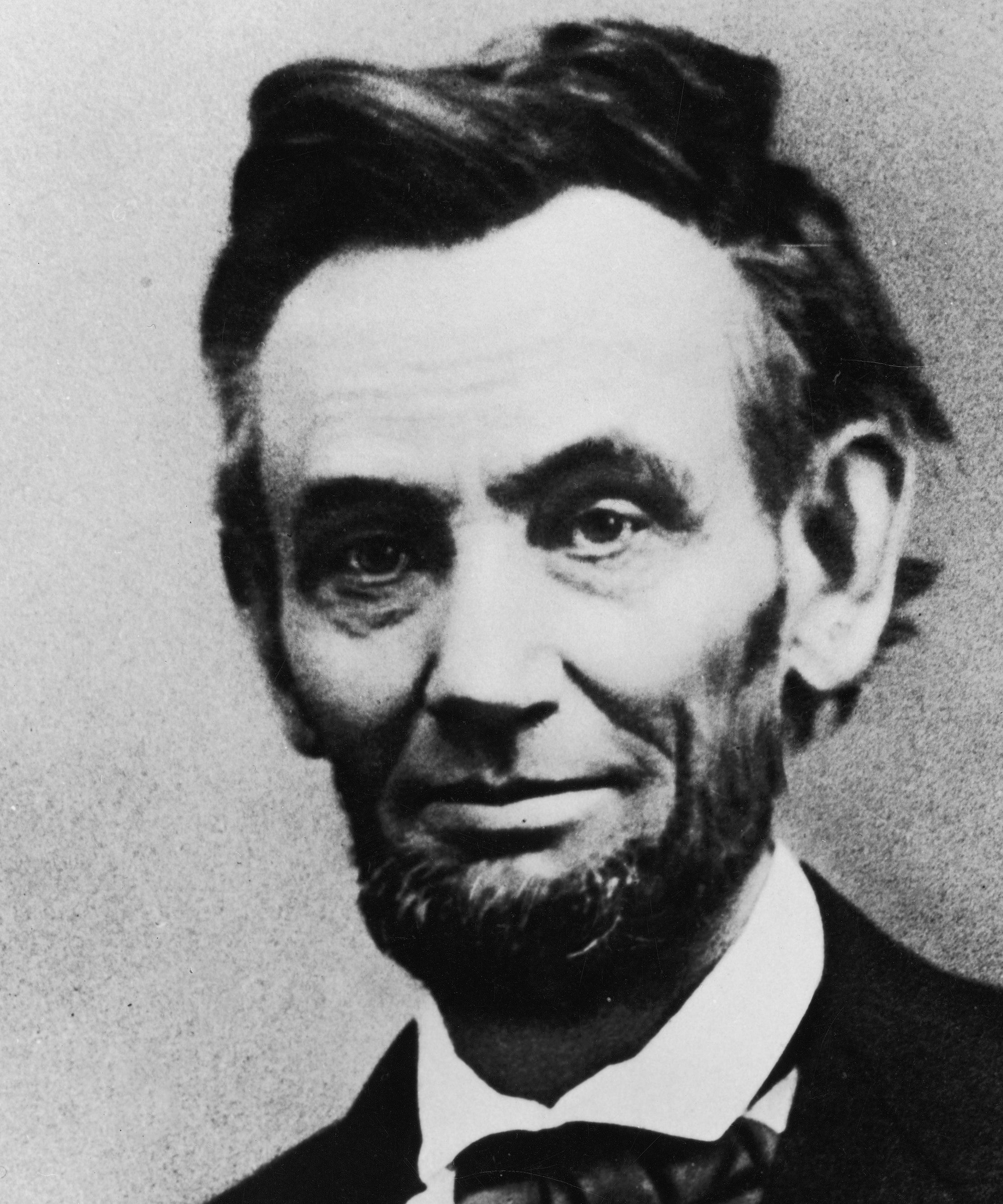

On February 19, 1862, with armies drilling for the spring Civil War campaigning season, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation. “It is recommended,” he wrote, “to the People of the United States that they assemble in their customary places for public solemnities on the twenty-second day of February instant, and celebrate the anniversary of the Birthday of the Father of his Country, by causing to be read to them his immortal Farewell address.” That was all.

On February 19, 1862, with armies drilling for the spring Civil War campaigning season, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation. “It is recommended,” he wrote, “to the People of the United States that they assemble in their customary places for public solemnities on the twenty-second day of February instant, and celebrate the anniversary of the Birthday of the Father of his Country, by causing to be read to them his immortal Farewell address.” That was all.