The author was a high school football player when a junior coach from West Point tried to recruit him. Years later, the player discovered who the now-famous coach was, and learned a valuable lesson.

-

Summer 2017

Volume62Issue1

This essay is part of a series of articles written by the readers of American Heritage entitled "My Brush with History" in which they recall meeting a famous personality or playing a small part of a momentous event. We invite our readers to continue to submit ideas to editor [at] americanheritage.com.

Early in the second month of 1953, I was summoned from study hall at White Plains High School. A college football coach wanted to see me.

Such recruiting visits were commonplace because the school’s football team had not lost a game during my three years there. Our quarterback, the high school coach’s son, was chosen as a high school All-American in his senior year. I played center and received my share of recruiting attention as a result of that reflected glory. One head coach, whose undefeated 1952 team was ranked number one, had offered to put me through a Baltimore law school if I would play for him. (I didn’t accept the offer and learned only years later that the law school was not accredited.)

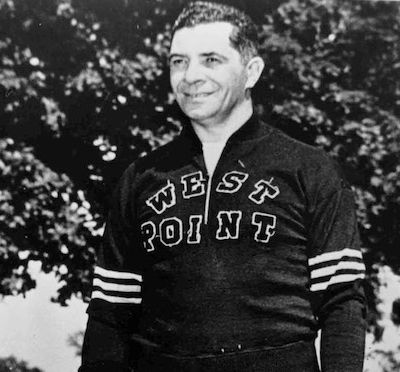

However, the coach I was summoned from study hall to meet that day in 1953 was different. He was not a head coach, and his team was a long way from a number-one ranking. The U.S. Military Academy at West Point (Army), where he was an assistant, had Columbia and Penn on its football schedule, and its team was not the powerhouse it had been in the forties.

But the coach I met that day was different in more important ways. Although he was obviously interested in me, he made no easy pledges of future help. Nor did he sugarcoat what West Point had to offer, or what it required. First and foremost, he told me, you were in the Army, and basic training was your initial obligation. Football would have to come later.

That coach, with thick glasses and black, curly hair, stood out over the years in my memory even though I soon forgot his name. He was the most honest person I met during that recruiting period. I had encountered a man of character, and even the obtuseness of adolescence could not hide that fact from me.

It took almost 30 years for me to realize who it was I had met that day. The revelation came by accident, and in some ways it was disturbing.

While watching a football game on television with my brother-in-law at my mother’s house, I told him about a kind letter I had received from the coach at USC when I sought a college transfer back in the fifties. In an effort to produce the letter, I searched a desk containing old correspondence; I never found the USC letter, but I stumbled on one from that Army assistant coach written days after our interview, inviting me to visit West Point.

The signature at the bottom was strong, careful (each letter was legible), and familiar:

VINCENT T. LOMBARDI

ASST. FOOTBALL COACH

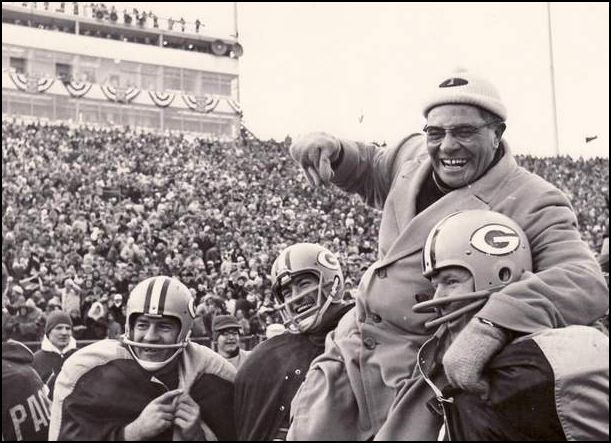

My 1953 interviewer was a football legend! He was the coach who led the fabled Green Bay Packers of the 1960s to victory in the first two Super Bowls, a man whose name had become synonymous with winning football.

I was impressed that I had harbored such a vivid memory of him without reference to his celebrity. The letter, discovered more than a decade after Coach Lombardi’s death, now hangs proudly in my offices.

But there were two troubling aspects to the discovery.

First, I could find no evidence that I ever answered the letter or its invitation. The ignorance of youth cannot be used to excuse that discourtesy.

Second, my memory of him did not seem to jibe with his celebrity image. The barrel-chested, gap-toothed martinet who prowled the sideline in a camels-hair coat could not have been the same thoughtful person who had interviewed me in 1953—a man who seemed more like a careful math teacher than a football coach. That person would not have believed that winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing—the quote famously associated with Lombardi.

While I could do nothing to dispel the first troubling aspect of my discovery, I was able to do something about the second. My pastor at the time, the late Msgr. Joseph P. Moore, had served as a West Point chaplain when Lombardi was there and knew him well. The coach had regularly attended 6:30 a.m. mass and had been a handball competitor of the priest. Monsignor Moore assured me that my memory was more accurate than the popular image. The coach had been a multifaceted person of high moral and ethical standards, he told me. Simply put, he was a man of character who knew there was more to life than winning.

This experience of discovery taught me important lessons about the difference between celebrity and character. It taught me not to take someone’s image as a definition of the whole person, and it taught me to pay attention to everyone I meet, because you never know where you will find the strength of character that inspires.