Hamilton's Other Half

Editor's Note: Bruce Watson is a writer, historian, and contributing editor at American Heritage. You can read more of his work on his blog, The Attic.

BROADWAY 2015 — As the musical winds down, the full cast returns. History, they sing, hinges on “who lives, who dies, who tells your story.” Washington shares his, then Jefferson, then Madison. But (SPOILER ALERT!) the final word falls to Eliza.

I put myself back in the narrative

I stopped wasting time on tears

I lived another fifty years. . .

Wait, what? We have watched her suffer the loss of a son and a husband. She must be in her mid-forties. Another fifty years? Who is this Eliza? “Hamilton” sings the praises of that “ten dollar scholar,” yet night after night Eliza steals the show. And without Hamilton’s other half, there would have been no show.

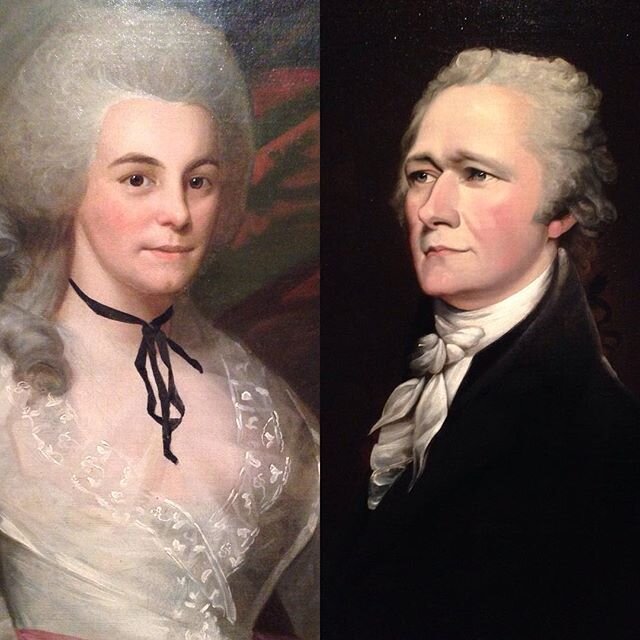

Elizabeth Schuyler was the middle daughter of a wealthy and landed general. Her older sister, Angelica, was also in love with the dashing Alexander, but Elizabeth won the “mind at work.” Meeting her in 1780, Hamilton wrote the third Schuyler sister, “She is most unmercifully handsome. . . so strange a creature that she possesses all the beauties, virtues, and graces of her sex without any of those amiable defects.” He would soon learn that her graces included a soul of silk and iron.

Married, Eliza did her duty — she bore children. She also charmed Jefferson, danced with Washington, put up with Aaron Burr, sir. When her husband publicly confessed to an affair, she left him — briefly. Returned and reconciled, she bore two more children, making eight. Then in 1801, darkness descended.

See also: The Boyhood Of Alexander Hamilton, by Dorothie Bobbe

Within three years Elizabeth lost her youngest sister, her eldest son in a duel, her mother, her father, and “my Hamilton.” He had kept his impending duel a secret. When borne back to Manhattan, he sent for her. He was suffering “spasms,” she was told, but upon entering his room, she saw the truth. She summoned seven surviving children. All were with him when he died, when iron replaced silk.

Working for Manhattan’s Society for Poor Widows with Children, she had already adopted an infant to add to their brood. In 1806, presented with six new orphans, Eliza co-founded the Orphan Asylum Society. For the next forty years, “Mrs. General Hamilton” ran the orphanage, tending to the care of 756 children. In her spare time, she tended to the orphaned reputation of her husband.

Without Hamilton’s other half, there would have been no show.

“After his death, his enemies were in power,” biographer Ron Chernow wrote. With Jefferson and Madison rising, Hamilton became “the evil genius of this country.” Tarred as a monarchist, a philanderer, Hamilton could not tell his story. So Eliza, after burning her own letters, took up the task. Death does not discriminate, as Aaron Burr sings. “It takes and it takes and it takes.” It was left to Eliza to give and give and give.

She interviewed veterans of the Revolution who had fought with her husband. She enlisted assistants to organize his papers. She corrected a myth — James Madison had not written Washington’s Farewell Address. Her husband had, reading it aloud to her. “Justice shall be done,” she insisted, “to the memory of my Hamilton.”

See also: The Fateful Encounter, by James R. Webb

Biographies of Founders poured forth, but none of her husband. She helped several scholars begin but each gave up. There were no papers — until Elizabeth lobbied Congress to publish them. Her youngest son finally began a bio, but before it came out, her own time approached.

In 1848, Elizabeth moved to D.C. where she raised funds for the Washington Monument. On July 4, she rode to the dedication ceremony in a carriage with President Polk, future president James Buchanan and a Congressman named Lincoln. The cordialities completed her presidential dance card. She had met every president from Washington to Lincoln.

On into her nineties, Mrs. General Hamilton lived in a townhouse near the White House. Dressed in black, she showed visitors her treasures. A locket containing a sonnet Hamilton had written her. A portrait of Washington plus the silver wine goblet he gave her during Hamilton’s scandal. But the highlight was the marble bust of her husband. “She gazed and gazed upon it,” one visitor remembered.

Ninety-seven year old Elizabeth Hamilton died in 1854, “another fifty years” after her husband’s death. His reputation had not been fully restored. Theodore Roosevelt called Hamilton “the most brilliant statesman who ever lived,” but it took a Broadway musical penned by the son of a Puerto Rican immigrant to bring up the house lights. “Immigrants — We get the job done.”

See also: The Self-Made Founder, by John Steele Gordon

Shortly before her death, Eliza sat back from a game of backgammon before the fire. “I am so tired,” she sighed. “It is so long. I want to see my Hamilton.”

On stage, as music swells, Lin-Manuel Miranda returns to lift Eliza’s hand, then vanishes into time. She steps to the front.

When my time is up

have I done enough?

Will they tell my story. . .

She clutches her chest, and sobs. The lights go out. The ovations begins.