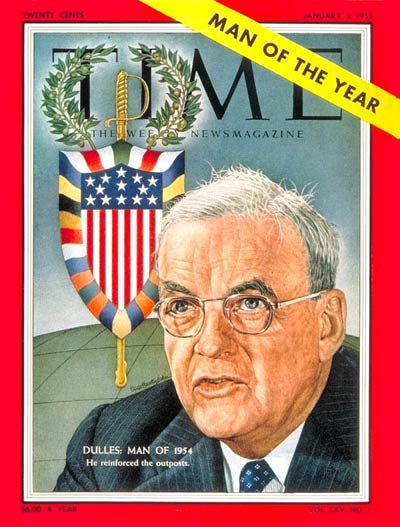

American foreign policy was a uniquely fraternal affair during Dwight Eisenhower’s presidency in the 1950s: John Foster Dulles served as Secretary of State, while his brother Allen led the Central Intelligence Agency.

-

July/August 2020

Volume65Issue4

David O. Stewart is the author of several histories and historical mysteries, including The Paris Deception, a novel set at the Paris Peace Conference that features both Dulles brothers as central characters. Previously, he previous wrote an essay for American Heritage on the 1807 trial of Aaron Burr.

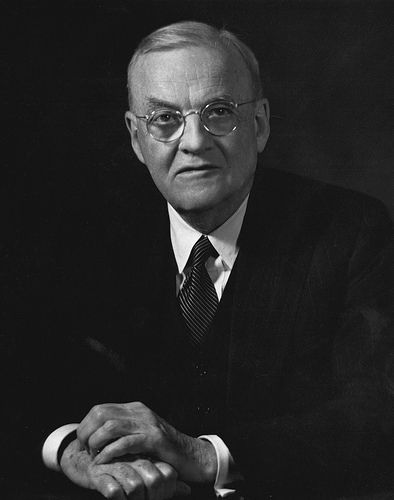

Secretary of State John Foster Dulles embraced a fervent anti-communism, pledging “massive retaliation” against communist aggression and “brinkmanship” in international confrontations. Often ponderous, the self-righteous diplomat was sometimes called the most boring man in America, spawning the inevitable gibe, “dull, duller, Dulles.” After a meeting with Dulles, a British prime minister observed, “His speech was slow, but it easily kept pace with his thoughts.” Comedienne Carol Burnett burst into prominence with the spoof tune, “I Made a Fool of Myself over John Foster Dulles.” Despite the mockery, Dulles’ deep convictions and mastery of diplomatic issues made him an unusually powerful Cabinet officer.

CIA Director Allen Welsh Dulles, four years younger and also a Princeton grad, delivered the family’s anti-communism in a very different package. He combined years of experience as a secret agent with a convivial manner and a restless eye for bed-partners. One Dulles sister numbered the ex-spy’s lovers in the triple digits. While Foster (as the elder brother was called in the family) cast rhetorical thunderbolts from rostrums in international conferences, Allen cheerily fancied himself a James Bond figure while plotting the overthrow of governments in Guatemala, Iran, and Cuba.

The brothers also had shared traits. Both logged prosperous years with New York’s premier corporate law firm, Sullivan & Cromwell, and each came to grief in electoral politics. In 1938, Allen ran for Congress in Manhattan’s Upper East Side but lost the Republican primary to an apostate Democrat. A 1949 appointment to a vacant Senate seat from New York gave Foster a running start on elective office, but four months later he lost a special election.

Yet their greatest shared quality, and greatest strength, was their family connection to international corridors of power. Their grandfather and their uncle each was secretary of state. Both men gave the brothers powerful shoves up the ladder of success, paving the way for the four of them to achieve a diplomatic prominence unmatched by any family in American history other than the Adamses of Massachusetts.

The Grandfather

The Dulles boys grew up in Watertown, New York, a remote community perched on the edge of Lake Ontario. Their father was a Presbyterian minister whose own minister-father spent five years preaching the gospel in India. Rev. Allen Macy Dulles required that his five children take notes on his Sunday sermons, and then explain the sermons at family dinner later that day.

Those early lessons took root in Foster’s heart, who would ever convey a rigid moralism and a mastery of scripture. Allen proved more resistant to Presbyterian discipline, becoming, in one observer’s phrase, “a genial satyr and an eternal dilettante.”

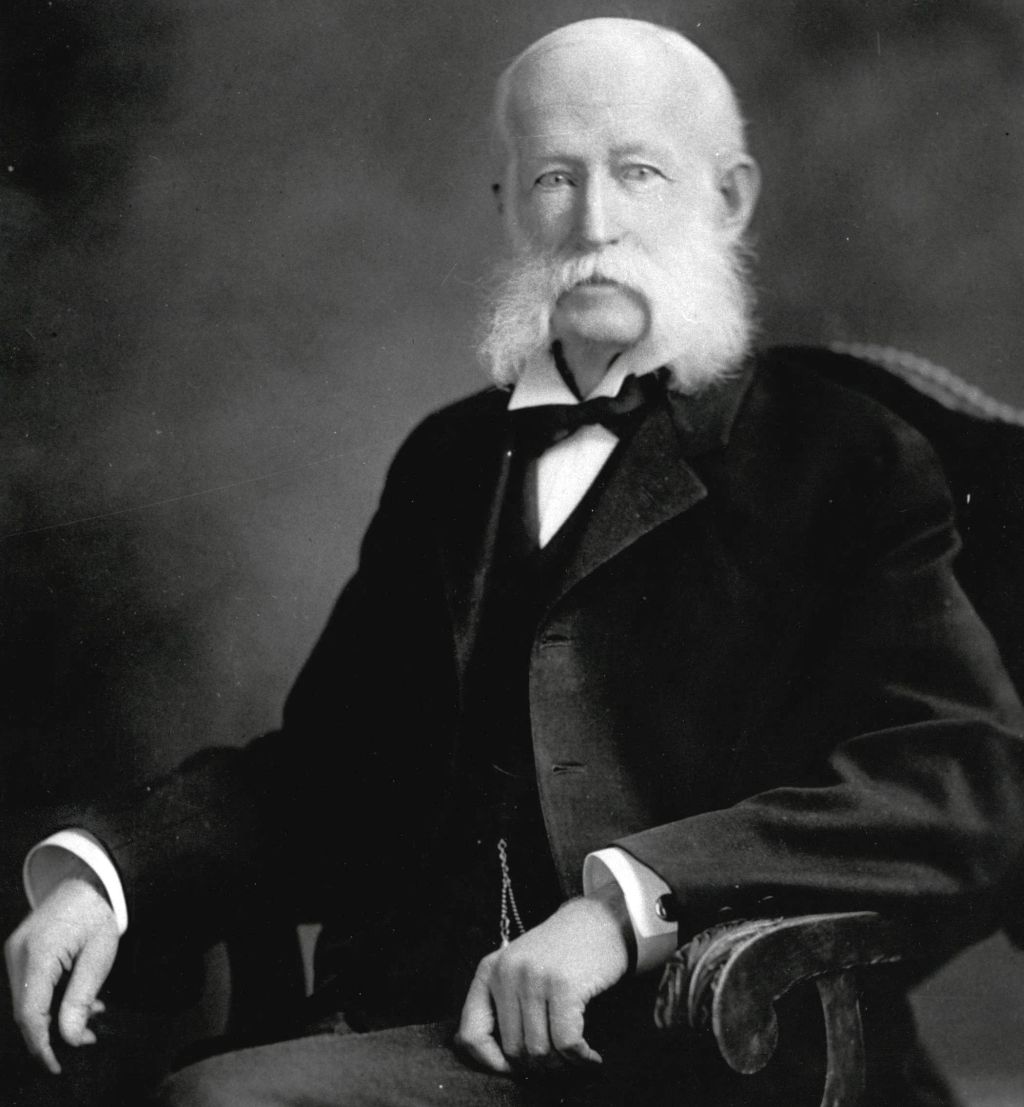

The lasting lessons for the Dulles brood came during summers spent with their maternal grandfather, John W. Foster, usually at his home in Washington, D.C. Originally from Indiana, John Foster rose in Republican circles after the Civil War and served as America’s minister to Mexico for seven years, to Russia for one, and to Spain for three. Nearing fifty, the urbane ex-diplomat built a high-octane law practice in Washington representing foreign governments, becoming something of an institution himself.

In an eight-month stint as secretary of state at the end of Benjamin Harrison’s presidency, Foster supported the 1893 overthrow of Hawaii’s Queen Liliuokalani and then negotiated a treaty to annex the island nation. Before the Senate could ratify Foster’s treaty, however, incoming president Grover Cleveland buried it, so annexation had to wait another five years.

One of the Dulles sisters breathlessly remembered the summer visits to Washington, where the Mexican ambassador lived next door and the Chinese ambassador was nearby. For their grandfather’s Monday evening receptions, young Foster and his sister pressed their faces to the windows to see the dignitaries arrive with “their coachmen and their footmen, and then somebody would get out all dressed in regalia.”

As the boys grew up, their grandfather included them in conversations with his high-powered guests and friends. At nineteen, Foster served as his grandfather’s aide at the Second Hague Peace Conference of 1907. Six years later, grandfather came to the rescue when Foster, fresh out of law school, had difficulty landing a suitable job. The old man asked the senior partner at New York’s Sullivan & Cromwell for the favor. His grandson started work there shortly thereafter.

When World War I erupted in 1914, the aging grandfather passed to his son-in-law, Robert Lansing, the responsibility of advancing the Dulles brothers. Lansing – Uncle Bert to the twenty-something brothers – had married John Foster’s other daughter. He combined law practice in little Watertown with diplomatic assignments that doubtless grew from his father-in-law’s sponsorship. A conservative Democrat, Uncle Bert joined the Woodrow Wilson’s State Department when war broke out. He succeeded William Jennings Bryan as secretary of state after Bryan could not reconcile his pacifism with Wilson’s escalating support for the Allies in the European war.

Lansing and the Dulles left behind the idealism of old John Foster. In a 1906 book, John Foster had applauded American foreign policy for eschewing espionage and deceit, “making it stand for the best ideals of mankind.” In office, Uncle Bert swiftly took a different road, establishing a Bureau of Secret Intelligence (BSI) and staffing it with secret agents authorized to investigate foreign saboteurs and gather intelligence. Ultimately, BSI sent agents overseas, as well.

Following family tradition, Lansing put his bright young nephews to work. In 1917, he sent Foster on a secret trip to Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panama to evaluate the risk of sabotage against the Panama Canal. He sent Allen, only twenty-four, to Vienna to try to entice Austria-Hungary to abandon the war. When the United States entered the fighting and closed its Vienna embassy, Allen moved to Bern, Switzerland, where he managed agents operating in the Austro-Hungarian empire.

In Bern, Allen acquired a tale he loved to tell later in life. One afternoon in 1917, eager to depart for a country weekend with two blonde “and spectacularly buxom” Swiss lasses, Allen made short work of a telephone call from a local Russian émigré named Ulyanov. Ulyanov – whose nom de guerre was Vladimir Lenin – demanded a meeting to deliver an urgent message to the United States government, but Allen couldn’t be bothered; he put off the tiresome Russian. On the next day, Lenin boarded a sealed German train that would take him to St. Petersburg for the purpose of undermining the Russia’s war effort, a mission that the Bolshevik leader performed admirably.

When peace came, the brothers seamlessly continued their advance in the world. Keeping a firm grip on Uncle Bert’s coattails, they landed plum positions with the American delegation to the half-year-long Paris Peace Conference. Shortly after the Armistice of November 1918, they settled in at Paris’ elegant Hôtel de Crillon, whose lobby was overrun with petitioners from across the globe – maharajahs, Zionists, Arab sheikhs in flowing robes, officials from China and Japan, and South Americans hawking their governments’ bonds.

Foster’s assignment covered the most critical issue before the victorious powers: what price should Germany pay for losing the war? Foster’s work on “reparations,” performed for the Central Bureau of Planning and Statistics, proved frustrating. The French especially, but also the British, insisted on recovering their military costs from four years of war. Foster argued forcefully that Germany should be treated no worse than criminals, who can be ordered to repay their victims but not the costs of hiring policemen. “The reparations made by the wrongdoers is made to the victim,” he insisted, “not to the guardian of the law.” His logic persuaded neither the French nor the British.

Allen had the better time of it in Paris, whose fleshpots he enjoyed to the fullest. Professionally, he began by briefing President Wilson on the exile groups clamoring to create new nations from the wreckage of the Austro-Hungarian, Turkish, and Russian empires. Winning the president’s trust, the twenty-six-year-old moved on to drawing the new boundaries for many of the emerging countries. Allen ultimately directed the steering committee that managed all of the conference’s business.

Pres. Herbert Hoover wrote about "The Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson" for American Heritage in 1958.

The precocious nephews were beginning to rival their Uncle Bert in influence. Indeed, relations between Lansing and President Wilson had turned sour, beginning with the secretary of state’s attempt to dissuade the president from attending the peace conference. Ignoring that advice, Wilson largely froze Lansing out of the conference deliberations. Wilson’s debilitating stroke in the autumn of 1919, while on a speaking tour to win support for his cherished League of Nations, led to a final rupture.

With Wilson largely disabled for months, Uncle Bert exercised greater control over foreign policy, but stumbled badly in a murky episode which may have involved Lansing suggesting that Vice President Thomas Marshall should assume the bedridden president’s duties. President Wilson, perhaps goaded by his wife, requested Lansing’s resignation in February 1920. Uncle Bert filled his last eight years with international law practice in Washington and the writing of two books about the peace conference.

From retirement, Lansing could take satisfaction in rising trajectories of Foster and Allen. For another 40 years, the Dulles brothers would hover near the apex of the American power structure, in private life and in high public office. Critics accused them of greater dedication to their clients’ corporate interests than to the nation’s needs, and of half-hearted opposition to Nazism. After another espionage stint in World War II, Allen recruited former Nazis to staff the security service of the new West German government. A few years later, the brothers became symbols of America’s iron-fisted opposition to what they deemed the world communist threat.

Foster would make the cleaner exit from public life, dying in office in 1959, after more than six years as the nation’s top diplomat. Washington’s international airport bears his name. Allen continued as CIA director beyond the Eisenhower years and into the Kennedy presidency, which led to the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in April 1961, masterminded by Dulles and the CIA. Six months after the debacle, President Kennedy eased Allen’s departure from the agency by presenting him with the National Security Medal.

The Dulles brothers combined plain talents with a vigorous cultivation of an Old Boy Network steeped in nepotism. A popular saying argues that people don’t remember how your opportunity arose, but what you made of it.

Actually, they remember both.