Recently declassified documents reveal that Alexander Haig and other White House staff actively worked to remove Richard Nixon — the president they worked for — from office.

-

October 2020

Volume65Issue6

Editor's Note: Ray Locker is the author of Haig's Coup: How Richard Nixon's Closest Aide Forced Him from Office and Nixon's Gamble: How a President’s Own Secret Government Destroyed His Administration.

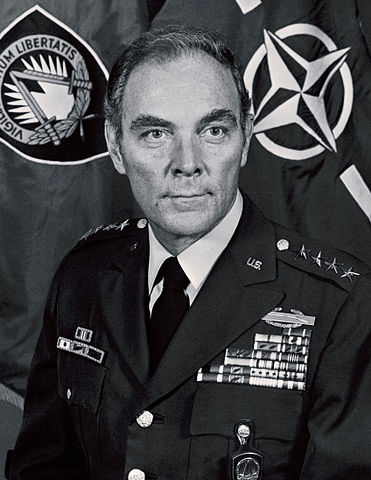

Emotional and breathless, Secretary of State Alexander Haig faced an anxious press corps in the White House briefing room at 4:14 p.m. on March 30, 1981. An assassination attempt had just been made on President Ronald Reagan, who lay anesthetized on an operating room at George Washington University Hospital. Haig had scrambled from the State Department to the White House to manage the crisis. A nervous, jittery nation needed to know someone was capable of making decisions in the White House.

“Constitutionally, gentlemen, you have the President, the Vice President, and the Secretary of State in that order,” Haig said. “As of now, I am in control here, in the White House, pending return of the Vice President.”

That brief moment in the White House, when he strove to display calm, forever marked Al Haig as impulsive and unstable as he appeared to grab for power and fill the vacuum created by the attempt on Reagan’s life. But it was not the first time Haig had assumed authority that was not his to take. Haig believed he was in control that day in 1981 because he knew what it meant to be in charge at the White House. During the fifteen months from May 1973 to August 1974, when he served as President Richard Nixon’s chief of staff, Haig was, in the words of Watergate special prosecutor Leon Jaworski, the nation’s “thirty-seventh-and-a-half president.”

While the thought of an insider coup in the White House still seems like an exaggerated season of “House of Cards” or “Scandal,” it actually did happen. During his fifteen months as President Richard Nixon’s chief of staff in 1973 and 1974, Alexander Haig created the circumstances that led to Nixon’s eventual resignation. It was Haig who engineered the exposure of the secret White House taping system that recorded all of the president’s conversation in the Oval Office, on his telephone and in a series of other rooms throughout the White House, the Old Executive Office Building and the presidential retreat in Camp David, Maryland.

During the final months of the Nixon administration, as the president desperately tried to withstand the onslaught of negative press reports, congressional investigations, and federal prosecutions spurred by the Watergate scandal, it was Haig who controlled the president’s agenda and determined who met with the president and whether to even tell Nixon about many of the decisions made in his name.

Haig stacked the deck against Nixon’s legal defense, hiring both Nixon’s main Watergate defender and the special prosecutor. He also forced the resignation of Vice President Spiro Agnew, under investigation for bribery and corruption, and engineered the selection of his replacement. And as Nixon careened toward resignation, it was Haig who shaped that departure and the pardon Nixon eventually received from his successor, Gerald Ford.

The Reliable Military Aide

Alexander Meigs Haig Jr. was born on December 4, 1924 in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, a well-tended suburb eight miles from Philadelphia. In 1947 he graduated from West Point, then served in a series of military postings, including under Gen. Douglas MacArthur in Japan and Korea and later in Cambodia during the Vietnam War. He returned in 1968 to a post as commander at his alma mater, where he remained at the closing of the Johnson administration and the transition to a new president, Republican former vice president Richard Nixon, who had lost a razor-thin election to Kennedy in 1960.

Perhaps Haig’s army career would have ended there. But as his national security advisor Nixon chose Henry Kissinger, whom military adviser Fritz Kraemer had discovered during World War II. By late 1968 Kissinger had established an international reputation as a leading thinker on nuclear weapons policy as a member of the Harvard University faculty. As he assembled his national security staff with a host of national security bureaucrats and Johnson holdovers, Kissinger sought the advice of Kraemer and Joseph Califano for the name of a reliable officer to be his chief military aide. They both recommended Haig.

Nixon gave his National Security Council a different look from that of Johnson, who often made policy through ad hoc meetings and lunches with advisors. Nixon’s system focused almost all authority for policy in the national security advisor and the president. As established in the secret National Security Decision Memorandum 2, which Nixon signed shortly after being sworn in on January 20, 1969, the various agencies would receive policy questions from the White House. The agencies would supply their recommendations, and then the NSC staff and Kissinger would analyze them before presenting Nixon with a series of options from which he would make his decision.

Haig was in the middle of it, gathering information from the Pentagon and sifting through the flood of paper in Kissinger’s overflowing in-box. Haig’s twenty years as a military staff officer, starting with MacArthur in Japan, served him well. Even before Nixon took office, Haig was sending Kissinger memos about how to manage the paper flow into the White House. He stayed at work when others went home. He watched his peers carefully and slyly undercut them. Kissinger increased his reliance on Haig.

Tapped Phones and a Potential Spy Ring

Soon, however, Haig’s Pentagon allies saw signs that Nixon was not the hard-liner they wanted. Nixon’s proposals and other secrets quickly appeared in the press, often just days or hours after they developed. A March 31 New York Times article included details from a March 29 memo from the Joint Chiefs of Staff opposing Nixon’s plan to give Okinawa back to Japan, a mere hours after the memo was sent to the secretary of defense from Joint Chiefs chairman Gen. Earle Wheeler. Leaks about Nixon’s response to a North Korean attack on a military spy plane, troop withdrawal plans for South Vietnam, alternative Vietnam policies, and a potential sale of fighter planes to Jordan also drew anger from Nixon.

Who could be the source of these leaks? The President heard regularly from Attorney General John Mitchell and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover that he needed to place wiretaps on the phones of suspected leakers, starting with Kissinger’s nominal deputy, Morton Halperin.

Kissinger resisted until May 9, when the Times published a story that contained details of the still “secret” US bombing of targets in ostensibly neutral Cambodia. Nixon had approved the secret bombing campaign, called Menu, in March after military leaders said they needed the air strikes to wipe out the border sanctuaries and an alleged North Vietnamese command center along the border.

Kissinger erupted when he read the story by reporter William Beecher at breakfast in Key Biscayne, Florida, where he had traveled with the president and his team. Kissinger called Hoover, who had been steadily prodding him to do something, and asked for Hoover’s help. By day’s end, after three more calls from Kissinger, Hoover had already ordered the first wiretap on Halperin’s home telephone. With Haig’s help, Kissinger identified two more wiretap targets on the NSC staff, Daniel Davidson and Helmut Sonnenfeldt, and a surprising fourth target, Col. Robert Pursley, the military aide to Defense Secretary Melvin Laird.

Hoover approved the wiretaps, but only with the signed authorization from the attorney general, who agreed. While most experts considered the wiretaps legal under the current laws, they remained controversial, and Hoover realized public sentiment had turned against the FBI’s freewheeling tactics. Hoover delegated the wiretaps to William Sullivan, his trusted lieutenant and Haig’s friend. “After a lifetime of service under Hoover, he had the weary air of a man who has been sifting other people’s secrets all his life and finding them not particularly interesting,” Haig wrote of Sullivan.

By February 1971, when the program stopped, the FBI had tapped the phones of seventeen government officials and journalists.

The wiretaps, Haig claimed, generated proof that one leaker was Daniel Davidson, a protégé of longtime Democratic diplomat and politician Averell Harriman. Haig quietly told Davidson he had been discovered and had to leave, which he did. Beyond Davidson, however, the taps found nothing, leading Sullivan to tell Hoover they should stop. Hoover refused, saying he would maintain the taps as long as Nixon wanted them.

Hoover also believed the taps gave him leverage, the reasons for which were detailed in a 1971 FBI memorandum: “It goes without saying that knowledge of this coverage represents a potential source of tremendous embarrassment to the Bureau and political disaster for the Nixon administration. Copies of the material itself could be used for political blackmail and the ruination of Nixon, Mitchell and others in the administration.”

The Pentagon Papers

By the middle of 1971 Haig’s rhythms at the White House were firmly established. He had a closer relationship with Nixon, who often tired of Kissinger’s emotional neediness and bypassed him to talk with Haig, who often fed some of Nixon’s more aggressive or paranoid instincts. Meanwhile, Haig and Kissinger talked behind Nixon’s back, often calling him “our drunken friend.”

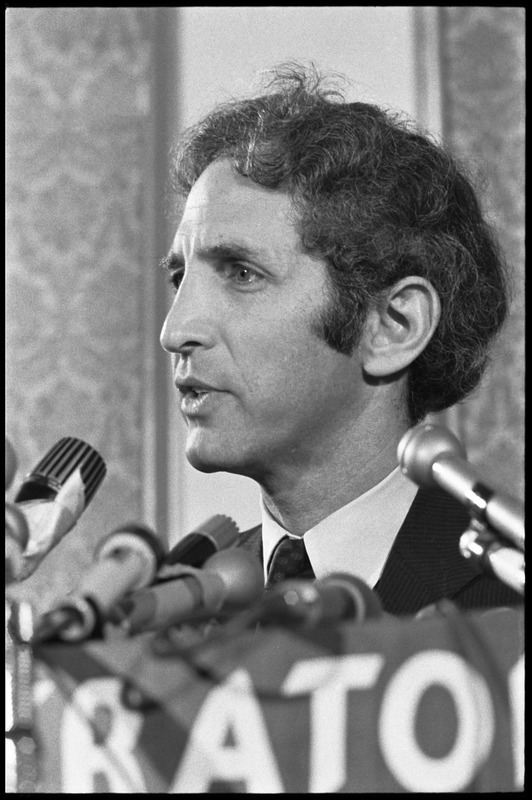

In June 1971 Haig inadvertently threw Nixon into a political crisis that would dog him for the remainder of his presidency. On June 12, the day after Nixon gave away his daughter Tricia at a glamorous wedding at the White House, a concerned Haig alerted Nixon to a story on the front page of that Sunday’s New York Times. The Times had obtained a copy of a massive history of the military’s involvement in the Vietnam War that was commissioned by Haig’s former boss, former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara.

Quickly dubbed the Pentagon Papers, the archive showed how successive administrations had lied and exaggerated about the Vietnam War despite their grave doubts. Daniel Ellsberg, a RAND analyst and former State and Defense Department assistant, had stolen the study and given it to the Times, which spent weeks assembling the documents into a narrative.

While Nixon had little to fear from the papers, which detailed previous administrations’ decisions and mistakes, Haig had greater risks. He had worked at McNamara’s side as the US involvement in Vietnam deepened, and Haig also had even deeper secrets that risked exposure, such as the long effort to subvert and overthrow Fidel Castro in Cuba. He told Nixon about “the goddamn New York Times exposé of the most highly classified documents of the war,” a story Nixon had not seen. “This is a devastating, uh, security break, of, of the greatest magnitude of anything I’ve ever seen,” Haig said.

Nixon wanted the FBI to investigate and destroy Ellsberg, just as the FBI had helped a young Nixon in the late 1940s when he went after Alger Hiss, a former State Department official accused of once being a communist. But this time, Hoover, stuck in a power struggle with Sullivan, declined to cooperate.

Nixon then authorized creating a White House team of investigators to do what Hoover would not and Sullivan could not do. Under the ostensible leadership of White House aide John Ehrlichman, the team consisted of longtime CIA operative E. Howard Hunt, former Treasury agent G. Gordon Liddy, and White House staffers Egil Krogh and David Young. Hunt tapped his former CIA colleagues for help, and Ehrlichman also sought aid from the agency’s deputy director, marine general Robert Cushman, who agreed to lend technology and assistance.

By September the investigations unit, nicknamed the Plumbers because they were supposed to plug leaks, had recruited a group of Cuban exiles with Bay of Pigs connections to travel to Los Angeles and help Hunt and Liddy break into the office of Dr. Lewis Fielding, a Beverly Hills psychiatrist who had treated Ellsberg.

The break-in yielded no dirt on Ellsberg, but it ensnared the White House in a criminal conspiracy.

A Break-in at Watergate

The year after the fall of the spy ring was one of triumph and budding tragedy for Nixon. His secrecy began to pay off as he traveled first to the China and then to the Soviet Union for summit conferences that opened diplomatic relations and cemented a significant arms control deal. In Vietnam, where Nixon had reduced the US presence to 24,000 troops by May, the South faced a spring offensive from the North that saw Nixon strike back with a bombing campaign led by B-52 bombers, which rained down 155,500 tons of bombs on targets across North Vietnam.

Then, early on the morning of June 17, 1972, a team of five burglars dressed in suits were caught by local police after they had broken into the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington’s Watergate office complex. The men included four Cuban exiles who had worked with E. Howard Hunt, the longtime CIA operative who worked with the White House Plumbers team. The fifth member of the break-in team was James McCord, another former CIA agent who was now the chief of security for Nixon’s reelection campaign. Hunt and fellow Plumber G. Gordon Liddy watched helplessly from a nearby hotel as police took away their partners, and they scrambled quickly to cover up the White House ties to the break-in.

Nixon had no advance notice of the break-in, but by June 23 he and Bob Haldeman, Ehrlichman, and White House counsel John Dean were eagerly working to cover up the White House connections, including the existence of the Plumbers team. Their main cover-up effort involved trying to use the CIA to block the FBI’s investigation into the Watergate break-in by claiming it would expose secret operations. Dean led these attempts through a series of meetings and calls with the agency’s deputy director, longtime army general Vernon Walters, who rebuffed him.

Haig had no involvement with any of the Watergate mess. He remained focused on Vietnam and the myriad other policy issues that dominated the administration. One of his former associates, the young navy officer Bob Woodward, was gaining a name for himself as a journalist covering the evolving Watergate story for the Washington Post. With his reporting partner, Carl Bernstein, Woodward had some of the first stories that tied the burglars to the White House and exposed the existence of a secret fund at the Nixon campaign that paid for political espionage and dirty tricks operations. Their reporting, along with that of reporters Seymour Hersh of the New York Times and Sandy Smith of TIME magazine, would begin to preoccupy the White House.

After leaving the White House for the military that year, Haig returned in May 1973. Between the Watergate burglary on June 17, 1972, and April 30, 1973, Nixon’s rigorously crafted White House had fallen apart. Not only did Haldeman and Ehrlichman resign that day, but so did Attorney General Richard Kleindienst; his Justice Department had repeatedly faltered in its attempts to prosecute Watergate cases.

Nixon also fired Dean, whose role in the break-in and subsequent cover-up were becoming appallingly clear to Nixon and his associates. Dean had started cooperating with prosecutors and Senate investigators earlier in April, swearing he would not be made the scapegoat for Watergate.

Haig’s Coup

Few presidents had ever confronted a month like May 1973. By rejoining Nixon, Haig entered a world of turmoil for which he was partly responsible. In Los Angeles, the administration’s case against Pentagon Papers leaker Daniel Ellsberg deteriorated each day. The series of FBI wiretaps that Haig and Kissinger oversaw with FBI official William Sullivan were about ready to burst into full view.

The White House would become collateral damage in the fight between Sullivan, jilted in his attempts to become the next FBI director, and Mark Felt, his rival at the FBI, who had initially revealed the existence of the wiretaps to TIME magazine. Another cover up — the spy ring inside the National Security Council run by the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff — also threatened to crumble.

By May 8, Nixon and Haig had already agreed to make Haig’s stay permanent, and Haig immediately affected the makeup of the government. In less than a week, Haig had put his stamp firmly on the White House. He brought in his former aide from Vietnam, Maj. George Joulwan, to start a series of early morning staff meetings “over which I presided for the purpose of making the president’s wishes on all pertinent issues plainly understood.” He had placed former CIA director James Schlesinger at the Department Defense, promoted former deputy director of operations Bill Colby to the head of the CIA, and made Pentagon official J. Frank Buzhardt the White House lawyer in charge of leading the Nixon defense.

And Haig steadily closed off access to the president.

“I knew that Haig was running the show,” said Len Garment, Nixon’s former law partner and one of his White House counsels. “Haig trusted Buzhardt and not me. My access was that I basically went in and talked to Haig. I was totally blocked. I mean there were times when I couldn’t get in to see” Nixon. And that, Garment said, undermined Nixon. “Obviously these are people who helped undo the vote of the people and who, in my theory, helped to grease the slippery slope.”

Meanwhile, to Haig, Nixon lamented how he had no surrogates to defend him against Dean and the growing number of critics and negative stories. Dean would soon bedevil Nixon with a series of interviews and claims about secret documents he had spirited from the White House on his departure.

Haig and Nixon would spend weeks trying to grasp the severity of Dean’s impending testimony before the Senate committee investigating the Watergate scandal. They needed to show that Dean was behind the cover-up, not the president.

That’s when Nixon made an admission that would alter his future and that of his presidency.

“I’ve got to tell you something you’re probably not aware of. There’s only one other person who’s aware of, and that’s Haldeman,” Nixon said. “[President] Johnson did this, and before him, Kennedy apparently did. Every conversation that’s ever been in this office or the Oval Office or Camp David has been recorded.”

Nixon knew the tapes could sort out the truth from the lies; now Haig knew it, too. Nixon’s admission meant Haig could now determine the truth for himself. Haig would say later that he suspected almost immediately after returning as chief of staff that Nixon was guilty. The tapes helped prove it. Haig would also spend the rest of his life lying about when he knew about the tapes, and those lies masked what Haig did to force Nixon from office.

In his memoirs, Inner Circles, Haig explicitly wrote that he learned about the tapes “on Monday, July 16,” when former Nixon aide Alexander Butterfield told the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, commonly known as the Watergate committee, about the taping system. “This was the first I had heard of the existence of an eavesdropping system that recorded every word uttered in the presence of Nixon, and it came as a total surprise to me.”

Haig also wrote that he advised Nixon to destroy the tapes once Haig learned they existed in July. However, the recorded conversations between Haig and Nixon from two months earlier reveal no such warning to the president. Nixon wanted to use the tapes, if necessary, to rebut his accusers. Haig, for reasons that would increasingly become apparent, wanted to keep them for his own purposes.

In the end, Haig eased Nixon out of office not to save the military or the presidency but to save himself. Nixon needed to go for many reasons. By his final year in office his mental condition alone justified his removal. He drank too much and was often absent during major crises. But Haig, in concert with Buzhardt, made it impossible for Nixon to stay, and then both men did everything to protect themselves.

By late June, Buzhardt was telling his friend, new White House aide and former Defense secretary Melvin Laird, that the tapes had revealed Nixon’s guilt in the Watergate cover-up. Anything that would put the tapes in front of the Senate committee or the special prosecutor would reveal Nixon’s guilt, and Haig knew it. By setting these events in motion, Haig had all but ensured Nixon’s demise.

In October 1973, Haig persuaded Nixon that he could fire special prosecutor Archibald Cox, and Attorney General Elliot Richardson would agree with it. That was a lie. Richardson had already told Haig that he would not agree to Cox’s firing. When Nixon acted, Richardson and his deputy, William Ruckelshaus, both resigned, a debacle that led the House to start impeachment proceedings against Nixon.

Haig needed Nixon to resign and be pardoned by Ford. A House impeachment and Senate trial would have exposed how Haig had leaked White House secrets, obstructed justice, and abused power. As Nixon’s deputy national security advisor, Haig led the White House campaign to have the FBI wiretap government officials and journalists to identify the leakers of White House secrets.

Those wiretaps were part of the surveillance techniques included in the impeachment articles, and both Haig and Kissinger had lied to cover their tracks. Haig had also cooperated with military leaders who were stealing secret documents from the White House and then leaking the details to derail his plans, an act the president had described as “a federal offense of the highest order.”

If Nixon had discovered it, that cooperation would have cost Haig his job and possibly landed him in prison. If Colson and Haldeman had known about Haig’s betrayal, they never would have recommended that Haig succeed Haldeman as the White House chief of staff.

By late July 1974, as it became obvious that Nixon was going to be impeached by the House, Haig set up a series of secret meetings with Vice President Gerald Ford and spelled out how Nixon could resign with the expectation that Ford would grant him a presidential pardon. While Ford and Haig would claim there was no quid pro quo in such an arrangement, Nixon clearly expected a pardon. Nixon called Haig repeatedly from his exile in California after he resigned, and Haig surreptitiously worked to get the pardon, which Ford finally granted on September 8, 1974.

Haig's Cover-Up

Haig had betrayed the president he had sworn to protect, and then engineered his cover-up. Less than forty-eight hours after Ford pardoned Nixon and eliminated the threat of a nasty criminal trial, Haig repaired to the den of his home in northwest Washington DC and met with the two reporters who had caused much of Nixon’s problems: Woodward and Bernstein of the Washington Post. Together they would write the inside story of Nixon’s final days, aided and abetted by Haig’s early and enthusiastic guidance.

Haig’s story, like so much of what he would say or write in the remaining thirty-five years of his life, was a series of interconnected falsehoods designed to hide what he had done and shift the blame to others. Haig had known Woodward since at least 1969, when the reporter was a navy lieutenant tasked with delivering secret messages from the Pentagon to Haig at the National Security Council offices in the White House basement.

Woodward had briefed Haig on military developments and issues critical to the Pentagon, according to three of the people who either sent Woodward there or knew about it: Adm. Thomas Moorer, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Woodward’s boss; Defense Secretary Melvin Laird; and Jerry Friedheim, Laird’s spokesman. Both Haig and Woodward would deny the relationship at the time, but, as with Haig’s claims about The Final Days, that was a lie.

Not only did Haig know Woodward well enough to meet with him and Bernstein at his home, he knew Woodward well enough to guide him in putting together their new book, which, Haig told them, “can’t deal with only [the] last days, [but] must go back to the last 15 months” specifically Haig’s time as chief of staff. That time, Haig said, brought “one shock after another until nothing surprised us.”

After Ford’s pardon, Haig was replaced by Donald Rumsfield, then went on to serve as the commander of NATO forces in Europe. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter’s defeat by Republican Ronald Reagan presented him with a new opportunity. Haig joined Reagan’s cabinet as Secretary of State in January, serving until 1982.

For an ambitious and cunning man like Haig, seizing control of the moment at the White House after Reagan had been shot in 1981 was just another routine piece of business. But his breathless attempt to assure calm triggered troubling memories for many who remembered his work for Nixon.

Shortly after Nixon’s departure, author and reporter Jules Witcover watched Haig in the VIP section of the Capitol after Ford addressed Congress and observed that Haig was “in a sense applauding his own deft achievement of presidential transition never contemplated in quite that way by the Founding Fathers.” Witcover witnessed “a bloodless presidential coup engineered by an army general, a man who had gravitated to the very right hand of one president and who, when that president fell, saw to a swift removal of the body.”

During the last twenty-eight years of his life, Haig would make a failed attempt at the Republican nomination for president in 1988, dropping out before the New Hampshire primary. In the 1990s Haig ran his own consulting company in Washington, where he represented some of the world’s rogue regimes.

In 1992 he published his memoirs, Inner Circles: How America Changed the World. Haig tried to offer a glimpse into his career and the people who influenced him — Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Joseph Califano, Robert McNamara, Henry Kissinger, and Richard Nixon.

The book is stunning in its attempts to reshape history and mislead readers. Haig lied about when he knew about the White House tapes, how he first tried to help Spiro Agnew and then pushed him to resign, how he covered up what he knew about the FBI wiretaps, and finally his involvement in the military spy ring. Historians who use Inner Circles as a guide to what happened during the Nixon administration will be led into a maze of Haig’s making that leads far from the truth.