Sixty years ago, Jack Ruby shot Kennedy assassin Lee Harvey Oswald. What was his motive? The Warren Commission lawyer who investigated Ruby reveals the killer’s state of mind.

-

Winter 2024

Volume69Issue1

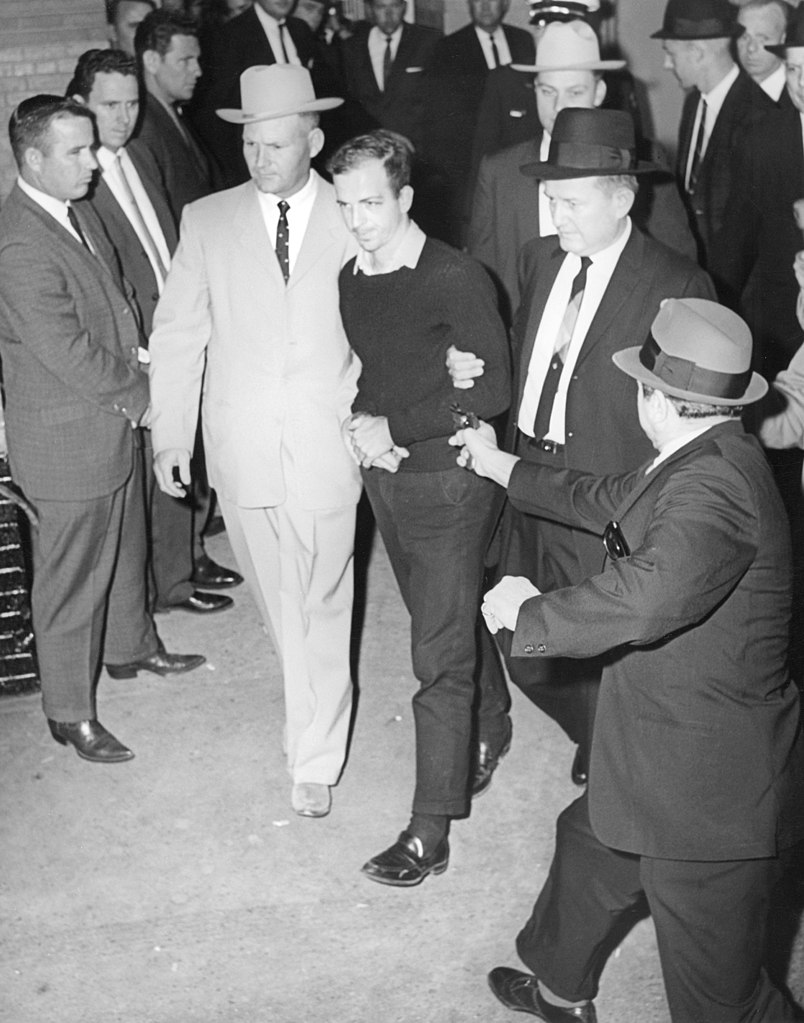

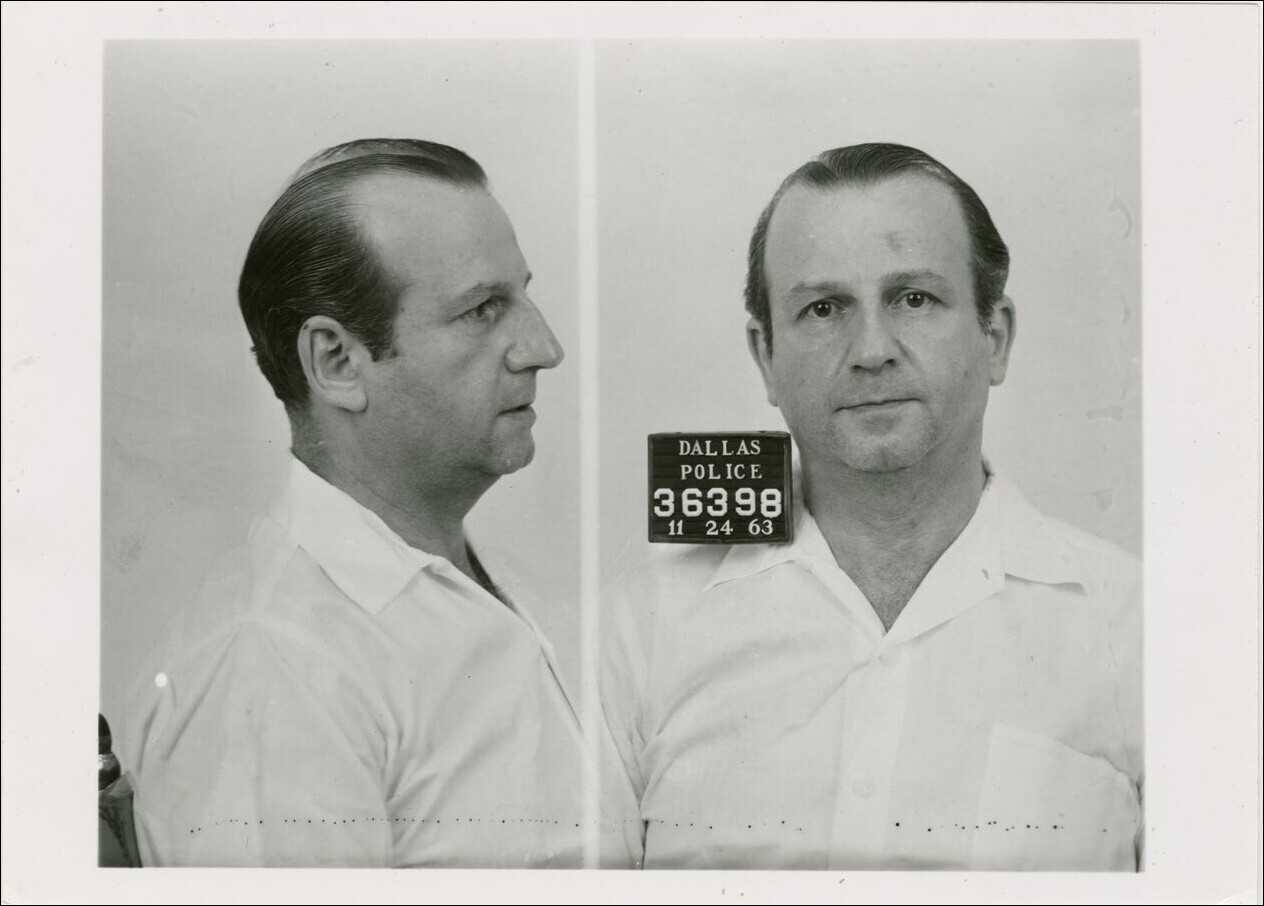

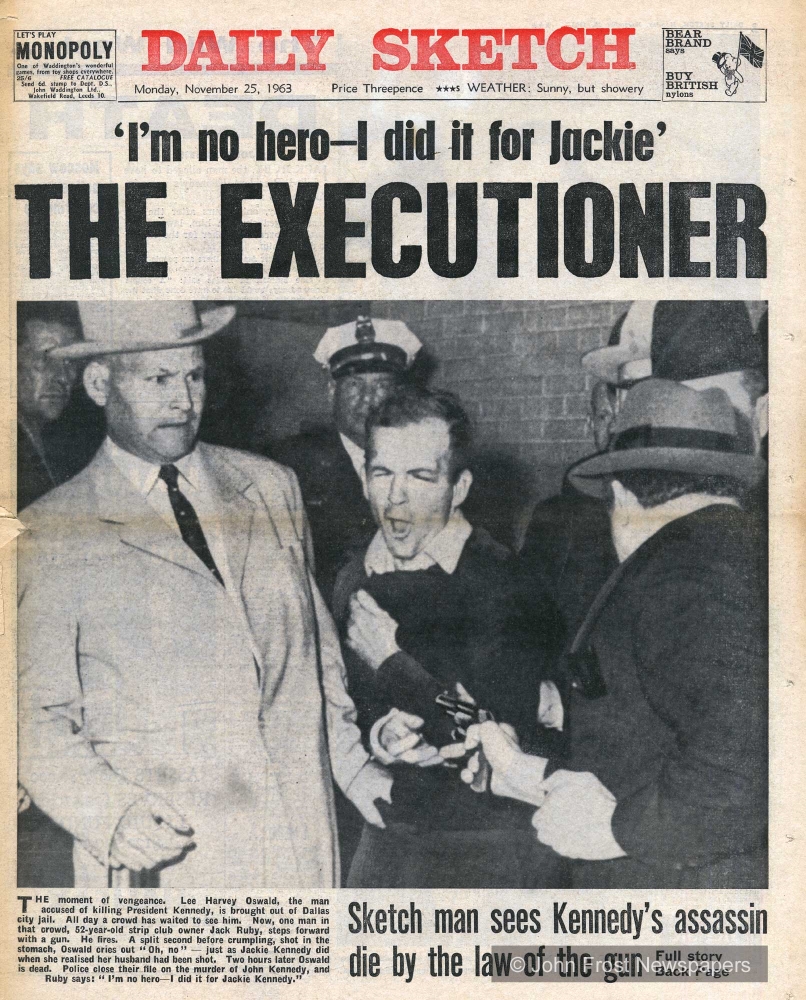

Editor’s Note: On November 22, 1963, 24-year-old Lee Harvey Oswald fired three shots from his sixth-floor perch in the Texas School Book Depository at John F. Kennedy as the president’s open-roof limousine was moving through Dealey Plaza in Dallas. The first shot missed. The second went through Kennedy’s upper back, then out his neck and into the body of Texas Governor John Connally. The third fatally hit the back of the president’s head. Two days later, as Oswald was being escorted through the basement of the Dallas police headquarters en route to the county jail, Jack Ruby, the 52-year-old owner of two local strip clubs, aimed his .38 Colt revolver point-blank at Oswald’s gut and killed him.

In the nearly 60 years since those two murders, a majority of Americans have believed that JFK and then Oswald were murdered as the result of a complex conspiracy, possibly involving the CIA, the Mafia, Cuban exiles in Miami, agents of Fidel Castro, and/or sundry other nefarious men in the shadows.

Who was Jack Ruby and why did he kill Oswald? We asked Burt Griffin, an investigator and legal counsel for the Warren Commission and a longtime judge in Ohio, to explain. The following material appears in his recent book, JFK, Oswald and Ruby: Politics, Prejudice and Truth.

The world needed to know why the charismatic president had been killed. But Jack Ruby’s murder of Oswald precluded a trial of Kennedy’s assassin. Normally, the question of why the crime occurred would have been pursued in a thorough examination of Oswald’s life in the days and months before Kennedy died. But Ruby’s action diverted public attention to a search for conspirators. The long-term consequence has been decades of public doubt as to whether the truth has been found.

I was one of the early searchers for the truth. Less than two months after President Kennedy’s death, I became a lawyer for the President’s Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy (popularly known as the Warren Commission). Ultimately, I was given primary responsibility for presenting evidence of whether Jack Ruby was part of a conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy, Lee Oswald, or both.

I made every effort to find evidence of Ruby’s involvement in a conspiracy. I found none.

I did find, however, considerable evidence of a motive that conspiracy theorists prefer to ignore — that Ruby, who was Jewish, killed Oswald because he feared that Jews would be blamed for Kennedy’s death. He hoped that, if a Jew killed Oswald, Jews would not be blamed for the Kennedy assassination.

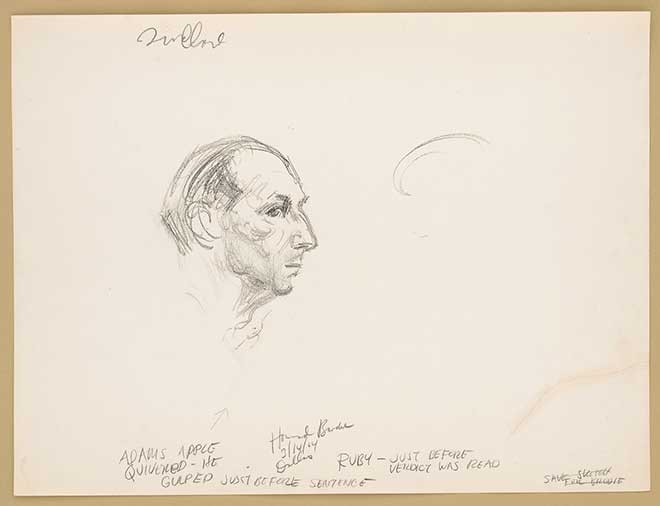

Jack Ruby’s family and his lawyers believed that Jack was psychotic — not only during his trial, but continuing until his death from cancer on January 3, 1967. As it happened, four days before Chief Justice Earl Warren heard Jack Ruby’s testimony in Dallas, my fellow Warren Commission investigator Leon Hubert and I took the testimony of Earl Ruby, Jack's brother. For Earl, there was no doubt that his brother became psychotic shortly after he shot Oswald, if he was not already psychotic at the time of the shooting.

Jack Ruby’s family believed he was psychotic and feared that Jews would be blamed for Kennedy’s assassination.

Earl believed that the dominant factor in Jack’s decision to kill Oswald was his fear that Jews would be blamed for the killing of the president. In support of that belief, Earl submitted a thirty-page memorandum prepared by Sol Dann, a Detroit lawyer who served as co-counsel on Jack’s appeal of his criminal conviction.

In that memo, Dann described the man who killed Lee Harvey Oswald as “an insane Jack Rubenstein, the son of pious Jewish parents who had suffered a lifetime of persecution as Jews.” Dann concluded that, when Ruby shot Oswald, he believed he would be acclaimed a hero. But, months later, by the time he was ready to testify to Chief Justice Warren, Ruby’s feelings had changed. He “now believes,” Dann wrote, that “he brought disgrace and shame upon all the Jewish people for all time . . . .”

Sol Dann cited a series of details from the trial — shocking to many readers today — that support his contention that Ruby had been victimized by anti–Semitism in Dallas in the early 1960s. Dann claimed that the prosecutor had inflamed the jury by referring to Jack Ruby as a “Jew boy from Chicago,” a “money-grubber,” and a “Jewish Messiah.” Dann’s memo confirmed for Ruby his belief that the death penalty was imposed because he was Jewish and that other Jews were being persecuted and executed for his behavior.

In 2015, fifty-one years after Leon Hubert and I took Earl Ruby’s testimony and read Sol Dann’s memo, a forensic psychiatrist from Australia, Dr. Robert M. Kaplan, offered his appraisal of what motivated Jack Ruby to kill Oswald. Considering Ruby’s personal and family history, his conduct beginning on November 22, 1963, and his medical history, Kaplan concluded, “Ruby’s behavior was driven by a belief that there was an anti–Jewish conspiracy behind the killing of the president. In addition, his use of amphetamines increased.... Ruby’s killing of Oswald reflected aspects of the American Jewish-immigrant experience, his dysfunctional personality, abuse of amphetamines, and the probable effects of a slight brain tumor.”

Friends, Employees, and Truth-Telling

The evidence was strong that Jack Ruby was mentally ill during his trial and at the time he testified before the Warren Commission. From the beginning of our investigation, however, my co-investigator and I believed that, whatever Jack Ruby said and whatever his mental state was, we had to seek information from other sources before accepting his credibility on any issue. Our assignment was to determine whether Ruby was part of a conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy and/or Lee Harvey Oswald.

Five witnesses — Ralph Paul, George Senator, Curtis Laverne (Larry) Crafard, Lawrence Meyers, and Alex Gruber — seemed especially important. Paul was Ruby’s business partner. Senator was his housemate. Crafard was an employee, and Meyer and Gruber were out-of-town friends. They had been in contact with Ruby on November 21, 22, 23, or 24, 1963.

We interviewed people around Ruby to see if they had advance knowledge that he intended to shoot Oswald.

We recognized that each person could be affected by self-interest and a desire to protect their friend. Their closeness to Ruby raised the possibility that they might have encouraged or conspired with him to kill Lee Oswald. At a minimum, they might have had advance knowledge that he intended to shoot Oswald on Sunday morning, November 24. In either event, they might have been reluctant to tell us the whole truth.

The Close Friend and Business Associate

Telephone records showed that, at 1:51 p.m. on November 22, Ruby made a brief call to Ralph Paul, who testified to us that Ruby had informed him that he was closing his night clubs for three days. Ruby, in fact, did that. At about 9:00 p.m. that evening, Ruby asked Paul to accompany him to Friday-night religious services, but Paul declined.

Shortly after 11:00 p.m. on Saturday, Ruby was at his Carousel Club. He made five short telephone calls, of one to three minutes each, between 11:18 and 11:48 p.m. Four were to Paul, and one was to an entertainer, Breck Wall, who was affiliated with the American Guild of Variety Artists (AGVA), a union that represented Ruby’s employees. Paul and Wall said that the calls related to a dispute Ruby was having with AGVA concerning favorable treatment of his competitors, who had not closed their clubs after Kennedy’s death.

The Employee and Vagabond

We were also suspicious that Ruby’s employee Larry Crafard had withheld important information from us. Crafard was a twenty-two-year-old with limited education. He had been employed by Ruby for a short time as a night watchman and general handyman. For those services, Ruby gave him room, board, and money for incidental expenses. Before that, Crafard had roamed the country, picking crops, working in carnivals, and doing odd jobs. He had a wife and two children. Yet, by November 1963, he wasn’t living with them. Leon Hubert observed to me that if he, Crafard, and I were tossed onto the street of a small western town without jobs, it would be Crafard who’d survive. Hubert and I would starve.

At about 5:00 a.m. on Saturday, November 23, Ruby phoned Crafard from his apartment, telling him to secure a small flash camera from the Carousel Club and wait for him and George Senator to pick him up. They drove to a billboard overlooking a Dallas freeway that proclaimed “Impeach Earl Warren.” Ruby wanted to photograph it. He thought the billboard was somehow connected to a full-page ad attacking President Kennedy that had appeared that day in the Dallas Morning News. Ruby suspected that the billboard, the ad, and the assassination were connected. Ruby was going to solve the crime.

After photographing the billboard, Ruby’s investigation proceeded to the main Dallas post office. There, he tried, unsuccessfully, to inquire who had the post office box with the number that was on the billboard. Thereafter, the trio stopped for coffee and a brief conversation about the billboard, the advertisement, and the assassination. By about 5:45 a.m., Crafard was back at the Carousel Club. Ruby and Senator were on their way home.

At about 8:30 a.m., Crafard telephoned Ruby. Ruby had asked him to feed the six dogs that lived at the Club. Crafard was calling about the food. Ruby, forgetting that he had told Crafard he was not going to bed, responded with anger. Crafard told the FBI that Ruby’s anger caused him to make a decision. He fed the dogs, took five dollars that he believed Ruby owed him, left a note for Ruby, and set off hitchhiking to Michigan.

To Leon Hubert and me, this was strange behavior. The president had been assassinated.

Did Crafard know something that we did not know? Did he suspect that Ruby was about to commit a crime and that he — Larry Crafard — might be implicated? As Hubert had said, Crafard knew how to survive.

We were able to bring Crafard to Washington to testify. He repeated what he had previously told the FBI: Ruby was difficult to work for; Ruby’s behavior after the assassination was bizarre – my word, not Crafard’s; Crafard had been thinking about leaving Dallas for about a week; Ruby had mistreated him; and he wanted to be with relatives in Michigan. Ruby had not said anything about killing Oswald. Crafard had no information about a conspiracy.

The Housemate

Unusual behavior by Jack Ruby’s fifty-year-old, unmarried housemate, George Senator, also aroused suspicions in Hubert and me. He described Ruby on Sunday morning as “mumbling, which I didn’t understand.... Then, after he got dressed, he was pacing the floor from the living room to the bedroom, from the bathroom to the living room, and his lips were going. What he was jabbering, I don’t know.” When Ruby left the apartment a few minutes before 11:00 a.m., Senator did not go with him.

Instead, Senator called his friend, William Downey, and offered to visit and make breakfast for Downey and his wife. Downey declined. Senator then went to the Eatwell Restaurant in downtown Dallas for coffee. A waitress following the news suddenly shouted that Jack Ruby had shot Oswald. “My God,” Senator gasped. He gulped down his coffee, ran to a telephone, and quickly departed. He went directly to the home of his lawyer, James Martin. That was the move that troubled us.

From Martin’s home, the two men drove to the Dallas police department, where Senator gave a statement. Was Senator seeking help for himself? Did he fear he would be implicated? Or did he turn to Martin to secure help for Ruby? Martin told investigators that Senator’s concern was for Ruby, not for himself.

Two months after we took George Senator’s testimony, we learned more. On July 18, 1964, Jack Ruby — at his own request — submitted to a polygraph examination. To the polygraph examiner, he filled in an important detail: Before leaving Senator on that eventful Sunday morning, Ruby expressed a hope that someone would kill Oswald.

In the end, we decided that Senator was not involved in a conspiracy of any sort with Ruby. We concluded that, on November 24, he was a frightened man enveloped by two shocking crimes.

The Friend from the Old Days in Chicago

We were also concerned with two of Jack Ruby’s friends who had more successful backgrounds than Senator and Crafard. They were Alex Gruber, a childhood friend who lived in Los Angeles, and Lawrence Meyers, a friend from Chicago who had been with Ruby on the evening of November 21. Could Meyers or Gruber be links in a conspiracy to kill either Kennedy or Oswald?

Meyers told the Warren Commission that Ruby was very distressed about the assassination and was especially disturbed that his competitors, Abe and Barney Weinstein, had not closed their clubs. He accused them of being “money-hungry Jews.” Meyers recalled to the Commission that Ruby said he was “going to do something about it.” What did that mean?

Leon Hubert and I assumed that, if Meyers were a conduit or confederate to Ruby in a plot to kill Oswald, he would not reveal it. Even if he were only an innocent friend, he might, as a witness, want to avoid harming Ruby. Nothing, however, about Meyers’ conduct suggested that he was part of a conspiracy.

We were more skeptical about Meyers’ description of Ruby’s emotional distress in their phone conversation on Saturday night. Meyers believed that, when Ruby said he had “to do something about it,” he was referring to the conduct of his business competitors. Ultimately, we accepted Meyers’ interpretation.

Though we accepted as true the descriptions that Meyers, Paul, and Wall gave us about Ruby’s emotions and worries, Leon Hubert and I made sure to include in endnotes to the Warren Commission Report references to anything that might contradict our conclusions.

The Boyhood Friend

The last of the possibly conspiratorial conversations that Ruby might have had with friends was a phone call to Alex Gruber in Los Angeles. Gruber and Ruby had been friends since grammar school days in Chicago. In the intervening years, Gruber had developed a successful business in Los Angeles. How Ruby and Gruber had maintained contact over the years was not clear, but Gruber told the FBI that, on about November 10, 1963, he visited Ruby in Dallas after a trip to Joplin, Missouri.

Gruber never explained the reason for the visit; however, on Sunday, November 17, at 9:28 p.m., Ruby called Gruber in Los Angeles from Dallas. Robert Blakey, former chief counsel to the House Select Committee on Assassinations, was one who believed that Ruby might have been inspired by organized crime to kill Oswald. Blakey has suggested, nonetheless, that Ruby may have been simply seeking help with financial problems.

Whatever the reasons for Ruby’s call to Gruber on November 17, at the time the president was assassinated, Ruby felt that his relationship with Gruber was important. At 2:37 p.m. on November 22, Ruby again telephoned Gruber in Los Angeles. Gruber told the Warren Commission that Ruby had talked about the possibility of purchasing a carwash business, said he was sending Gruber a dog, and became so emotional about the president’s death that he ended the conversation abruptly, having lost emotional control.

As we examined Jack Ruby’s contacts with employees, friends, and acquaintances between November 21 and 24, we found no evidence of a plan to kill President Kennedy or Lee Oswald. We needed, however, to look at Ruby’s conduct in more detail.

Jack Ruby: The First Conspiracy Investigator

To understand why Jack Ruby killed Lee Oswald and whether he was part of a conspiracy—either to assassinate President Kennedy or to kill Oswald— Leon Hubert and I believed it was necessary to detail Ruby’s activities from the first time someone might have known of President Kennedy’s trip to Dallas until Ruby shot Oswald. We compiled an exhaustive account of Ruby’s activities in that period and obtained an extensive record of his earlier history, friends, employees, and associates. We checked the interests and activities of those friends, employees, and associates. We verified their claims of contact or lack thereof through telephone records and other witnesses. Nothing connected any of those people to Ruby entering the Dallas police garage or killing Oswald — or in any way to the president’s assassination.

Leon and I were both satisfied that Jack Ruby was not part of any conspiracy. What became most important to our understanding Ruby’s conduct was the precise chronology of those activities and his attendant emotions from the time he heard the president had been shot until he was arrested for shooting Oswald. To us, what seemed most significant was Ruby’s distress over the president’s assassination, his fixation on Bernard Weissman’s anti–Kennedy ad that appeared in the Dallas Morning News on the day of the assassination, his fear that Jews would be blamed for the president’s death, and his effort to solve the crime of the century.

Ruby First Hears of the Assassination

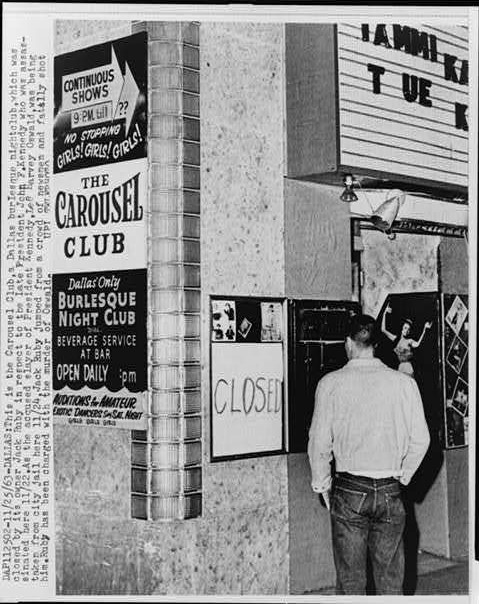

By 11:30 a.m. on November 22, 1963, Jack Ruby was at the advertising office of the Dallas Morning News placing ads for his two nightclubs, the Carousel Club and the Vegas Club. Newspaper employees recalled Ruby expressing concern about the financial condition of his businesses. They also recalled his complaining about a black-bordered advertisement attacking President Kennedy that the newspaper had run that day. It appeared to be signed by one Bernard Weissman as chairman of something called the American Fact-Finding Committee. As disrespectful as the ad seemed to Ruby, what troubled him more was that Weissman seemed to him a Jewish surname. He couldn’t believe that anyone Jewish would be associated with such an ad.

At approximately 12:45 p.m., while still at the Morning News, Ruby heard that the president had been shot. One newspaper employee recalled that Ruby appeared obviously shaken and “sat for a while with a dazed expression in his eyes.” It is a matter of dispute as to whether Ruby then went directly to his Carousel Club or first to Parkland Hospital, where the president had been taken.

Seth Kantor, an Associated Press reporter who knew Ruby, wrote on November 25, 1963 that Ruby had approached him at Parkland Hospital barely a minute before the president’s death was announced at 1:33 p.m. With tears in his eyes, according to Kantor, Ruby said, “This is horrible. I think I ought to close my places for three days because of this tragedy. What do you think?”

Yet Ruby denied to the FBI and the Warren Commission that he had gone to Parkland Hospital. The Commission failed to ask Ruby if he had talked to Kantor at Parkland Hospital or anywhere else on the day of the president’s death. Leon Hubert and I were satisfied that Ruby had spoken to Kantor that day, but we thought that, in the excitement of the November 22 weekend, Kantor was probably mistaken about the time and place. We checked possible driving times between Parkland Hospital and Ruby’s Carousel Club. We decided that it was more likely that the conversation had occurred elsewhere on Friday afternoon or evening.

Five decades later, I am less certain that our skepticism was well-placed and that Kantor’s memory was wrong. Kantor’s memory was fresh when he wrote his Associated Press article. The question exemplifies the problem of two eyewitnesses with contradictory memories and contradictory interests. Although difficult, it was possible for Ruby to drive from the Dallas Morning News to Parkland Hospital to his Carousel Club in the time available.

Ruby was an excitement hound. It would be characteristic of him to follow the news of the tragedy by driving to the hospital. But why should he have forgotten his trip to the hospital? And why should he later deny having made the trip?

In any event, Ruby arrived at his Carousel Club no later than 1:45 p.m. By then, he knew that the president had died. He made numerous calls to friends and family. He told his employees that the club would be closed for the next three nights.

Over a course of about six hours, Ruby shopped for weekend food and made at least ten phone calls to relatives and friends in Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, and Irving, Texas. He also called his synagogue twice to determine if Friday services would be held. He prepared signs to announce the temporary closing of his clubs and made arrangements with the Dallas afternoon newspaper, the Times-Herald, to place ads about the closings. He was described as grief-stricken by all who came in contact with him.

Friday Night, November 22

From about 5:30 p.m. to 7:30 p.m., Ruby was at his sister Eva Grant’s apartment for dinner. From there, he went to his own apartment and called his business partner, Ralph Paul, who said he wouldn’t go to temple with Jack. Arriving late at the services, Ruby spoke to Rabbi Silverman after his sermon in which he had lamented President Kennedy’s death. When interviewed by the FBI on November 27, 1963, the rabbi recalled that Ruby was not a regular at temple services and that he seemed in tears over the president’s death.

After the temple service, Ruby drove past some competitors’ night clubs to see if they had closed. They had not. That distressed him. When he heard on the radio that police officers were working late, he stopped at a delicatessen and purchased eight kosher sandwiches and ten bottles of soft drinks. He then called the police department and learned that the officers had already eaten.

Still, Ruby drove to the police station and ingratiated himself with out-of-state reporters. He told police that he was a translator for the Israeli press. At 11:30 p.m., prosecutor Henry Wade and Police Chief Jesse Curry held a press conference. Oswald was presented to the press. Ruby was there, pencil or pen and a small notebook in hand.

When Wade described Oswald as belonging to the “Free-Cuba Committee,” Ruby joined a few reporters in shouting to Wade that the committee’s proper name was the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC). It was not surprising that Ruby knew of the FPCC. From the time that Oswald was arrested, the airwaves had been filled with background on him, and the committee’s correct name was being bandied about by reporters at the police station.

When the press conference ended, Ruby approached the prosecutor, saying, “Hi Henry.... Don’t you know me? ... I am Jack Ruby. I run the Vegas Club.” Ruby then began distributing cards to the Carousel Club—one to Justice of the Peace David Johnston and another to Ike Pappas, a reporter for New York radio station WNEW. When Pappas had difficulty getting Wade’s attention, Ruby directed Wade to Pappas. Thereafter, Ruby brought Wade to a telephone line he’d opened to radio station KLIF, and directed KLIF reporter Russ Knight to Wade.

Ruby had succeeded in building his relationships with the press and police and telling them about his night clubs. From the police station, he went to KLIF, arriving at about 1:45 a.m., with his sandwiches and soft drinks. During the 2:00 a.m. newscast, Russ Knight credited Jack Ruby with arranging the interview with Henry Wade.

By then, Ruby’s grief was not as pronounced, but his interest in being a sleuth had grown. He suggested to Knight that the assassination had been the consequence of Dallas radicals—meaning the right-wingers who hated Kennedy. From KLIF, Ruby’s next stop was the Dallas Times-Herald. He needed to look over the ads he had ordered for closing his clubs.

En route, he encountered one of his dancers, Kay Helen Coleman, and her fiancé, Dallas police officer Harry Olsen. Ruby told the Warren Commission that officer Olsen was very upset about Oswald. Ruby alleged that, in a lengthy conversation, Olsen told him, “They should cut this guy inch by inch into ribbons,” and Ms. Coleman added, “In England, they would drag him through the streets and would have hung him.”

At the Times-Herald, employees remembered Ruby as “pretty shaken up” but excited that he had attended Oswald’s press conference and had been able to arrange interviews for reporters. He also mentioned the Weissman ad, saying that it was an effort to discredit the Jews.

Ever the promoter, Ruby demonstrated a twist-board that he was selling. This was an exercise and weight-loss device consisting of two pieces of hardened materials joined together by a lazy-susan bearing so that one could twist back and forth while standing on it. Ruby got aboard and did his twist.

By this time, the Weissman ad and the possibility that Jews would be blamed for the murder of President Kennedy had become an obsession with Ruby. It was not an unfounded obsession. This was 1963. Anti-Semitism was pervasive in America. It was more evident in Dallas than in many other cities. In January, a Dallas segregationist had burned a cross on the lawn of Jack Oran, a Holocaust survivor. Oran had been speaking out against intolerance. The segregationist was fined ten dollars.

On the night before Easter Sunday in 1963, neo–Nazis put stickers reading “We are back” on the homes of Dallas Jews, including that of Dallas department-store magnate Stanley Marcus. A few homes were vandalized. The next day, swastikas were placed on the windows of retail stores owned by Jewish merchants in Dallas, among them the fashionable Neiman Marcus department store. The next week, vandals painted bright red swastikas on Temple Emanu-El, the oldest Jewish temple in Dallas. The vandals left a message claiming that a bomb was planted there, but the police found none.

Some of the vandalized stores were only a few blocks from Ruby’s Carousel Club. All of the incidents were the subject of articles in the Texas Jewish Post. Ruby must surely have been recalling incidents like these when he talked about the Weissman ad to Times-Herald employees in the early morning hours of November 23.

From the Times-Herald, Ruby drove to his apartment. He had not slept at all that night. Arriving at about 4:30 a.m., he wakened his housemate, George Senator, who later testified to the Warren Commission that Ruby began discussing the Weissman ad. Ruby, he said, recalled seeing a billboard on a Dallas roadway urging the impeachment of Earl Warren, and wondered if the same people had sponsored both the billboard and the Weissman ad.

After a few minutes, Ruby made his call to Larry Crafard, telling him to get the Polaroid camera at the club, and wait for him and George Senator. The three men drove to the Impeach Earl Warren billboard near Hall Avenue and the Central Expressway. Ruby copied the name and post office box number on the sign. They photographed the billboard.

Senator told the Commission, “I heard him say, ‘This (meaning the sign and the Weissman ad) is the work of the John Birch Society or the Communist Party or maybe a combination of both.’”

The three men drove next to the main post office. There, Ruby tried and failed to secure from a postal worker the names of those who had rented the post office boxes for the billboard and the Weissman ad. After that, they drove to a coffee shop, where a thirty-minute conversation ensued about the two political advertisements.

After returning to his apartment, Ruby seems to have got some sleep, although he was wakened by a call from Larry Crafard. Later that morning, he received a telephone call from Marjorie Richey, a Carousel Club waitress. To the Commission, Ms. Richey described Ruby as talking in a shaking voice. She believed it was over the assassination.

Saturday Afternoon, November 23

Ruby recalled to the Commission that, sometime between noon and 1:30 p.m. on Saturday, November 23, he drove to inspect the wreaths at Dealey Plaza, then returned home, went back downtown, and called KLIF announcer Ken Dowe. A police officer at Dealey Plaza remembered Ruby as having been choked-up, almost in tears. At about 3:00 p.m., Ruby arrived at Sol’s Turf Bar. There, he talked with Frank Bellochio, a jeweler. Bellochio remembered an impassioned Ruby pointing to a copy of the Weissman ad and showing him the photo he had taken that morning of the Impeach Earl Warren billboard. Linking the billboard and the ad to anti–Semitism in Dallas, Ruby said he regarded the photos as a news scoop.

Without saying goodbye, Ruby left Bellochio abruptly. He then called his attorney, Stanley Kaufman, at about 4:00 p.m. The Weissman ad was very much on Ruby’s mind. By this time, Ruby had checked the Dallas phone directory, but had not found Weissman’s name. Kaufman recalled, “Jack was particularly impressed with the black border as being a tipoff of some sort—that this man knew the president was going to be assassinated.” Ruby told Kaufman that he had taken a photo of the Impeach Earl Warren billboard and had gone to the post office to be helpful to the police. At Kaufman’s suggestion, Ruby checked a Dallas street directory, but couldn’t find Weissman’s name.

When Ruby arrived at Eva Grant’s apartment an hour or two after leaving the Turf Bar, he continued to be obsessed with the Weissman ad. He told Eva that he had not been able to find Weissman’s name in the city directory. Both Eva and Jack believed that the inability to find Weissman’s name confirmed that the ad, the billboard, and the assassination were connected and were an effort to implicate the Jews. Ruby then called Russ Knight at KLIF and asked who Earl Warren was.

Saturday Evening

At about 8:30 p.m. on Saturday evening, Ruby called his friend, former Dallas police officer Tom O’Grady, who had once worked for Ruby as a bouncer. Ruby mentioned that he had closed his night clubs, criticized his competitors for remaining open, and mentioned the Impeach Earl Warren billboard.

By 9:30 p.m., Ruby was back at his own apartment. He received a phone call from one of his dancers, Karen Carlin, professionally known as Little Lynn. She had come to the Carousel Club expecting to be paid. Because she expected the club to be open, Ruby became angry, but he agreed to give her money.

In an apparently depressed mood, he called his sister Eva, who suggested that he call a friend. Ruby then telephoned Lawrence Meyers, the visiting friend from Chicago, with whom he’d had dinner two nights earlier. Meyers recalled to the Warren Commission that Ruby became highly critical of his competitors, Abe and Barney Weinstein, for not closing their clubs, and said, “I’ve got to do something about this.” Ruby and Meyers agreed to have dinner together the next evening.

A Flurry of Phone Calls

Ruby returned to his sister’s apartment. At 10:44 p.m., he called his business partner, Ralph Paul, who later remembered both Ruby and Eva Grant being in tears as they discussed the assassination. After that call, Ruby went to the Carousel Club, where, over the course of the next hour, he made the several brief calls to Paul and Breck Wall.

Our Suspicions

Ruby’s activities on Saturday aroused suspicions in Hubert and me. Officer Olsen and Kay Coleman had said that Oswald should be killed. Why had Ruby called Tom O’Grady, his ex-bouncer and former policeman? Ruby’s conversations with Ralph Paul and Lawrence Meyers also suggested the possibility that he was thinking about killing Oswald.

We asked the FBI to do background and telephone checks on those individuals. No leads were there. Our conclusions were that Ruby had called Breck Wall and Ralph Paul because he was genuinely concerned about the competition he was getting from the Weinsteins, the disrespect that their failing to close their business could bring upon Jews, and AGVA’s alleged mistreatment of him. Based on the multiple accounts describing his obsession over the Weisman ad and his photographing the Impeach Earl Warren billboard, we were satisfied that Jack Ruby’s distress over the Weissman ad was genuine, as was his belief that the ad, the billboard, and the assassination were connected.

Sunday Morning, November 24

Ruby got up sometime between 8:30 and 9:00 a.m. The cleaning lady at his apartment called him at about that time. She found him “terrible strange.” He seemed not to comprehend who she was, although it was her custom to clean on Sundays. George Senator confirmed Ruby’s disorientation that morning.

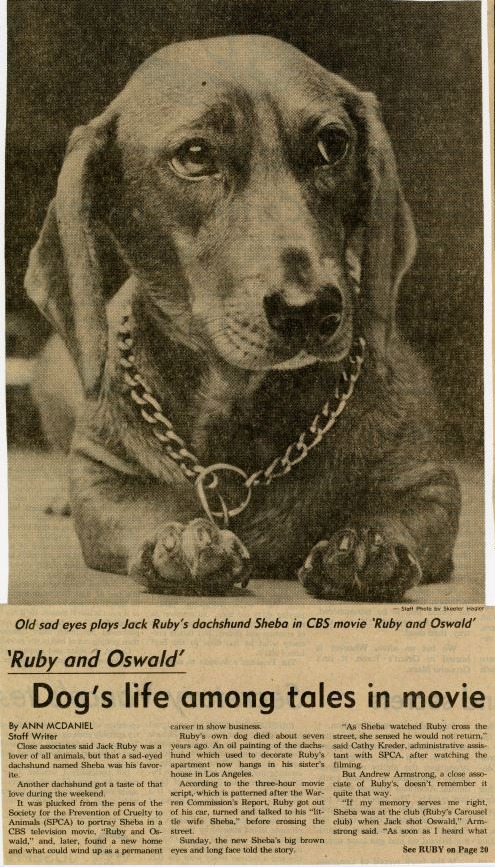

At 10:19 a.m., Little Lynn telephoned. She still needed money. She asked for twenty-five dollars because her rent was due and she needed to buy groceries. Ruby said he was going downtown, anyway. He would send her a money order from Western Union. A few minutes before 11 a.m., he left, taking his beloved dachshund, Sheba, along with a portable radio, a revolver, and $3,000 in cash. It was during that drive, Ruby told the Commission, that he first thought about killing Oswald, if he could. His priority for the moment was sending a money order to Little Lynn.

The Western Union office was on Main Street, one block from the police station where Oswald was being held. The normal driving time to Western Union was about fifteen minutes. Ruby parked his car in a lot across from money-transfer office. He left his billfold and car keys in the trunk, and locked the trunk. He left Sheba in the unlocked car, and placed the trunk key in the glove compartment. He took with him $2,000 in cash, leaving $1,000 in the car, and then walked across the street to Western Union.

Once there, he waited for another patron to complete a transaction. At 11:17 a.m., he finished sending a money order to Little Lynn. From there, he walked to the basement garage of the Dallas police station. At 11:21 a.m. C.S.T., surrounded by police officers, news reporters, and TV cameras, and in full view of a television audience of millions, Jack Ruby shot Lee Harvey Oswald.

Dallas police detective Thomas McMillon, who was standing nearby, would remember Ruby saying, “You rat son of a bitch! You shot the president.” A few minutes later, while guarding Ruby on the police department’s fifth floor, Detective Barnard Clardy would hear Ruby say, “If I had planned to kill Oswald, my timing could not have been more perfect,” and “Somebody had to do it. You all couldn’t do it.” Ruby later denied making any such statements. Secret Service Agent Sorrels did not report them. The words recalled by McMillon and Clardy may not have been accurate. The tone and meaning probably were.

Ruby and Organized Crime

To Leon Hubert and me, a brazen shooting amid dozens of police officers and media personnel did not have the earmarks of a planned conspiracy. What rational conspiracy would involve a killing in which the gunman — especially one who liked to talk — would be immediately captured? We were well aware, however, that many in the public suspected that Ruby had been a part of a plot by organized crime to kill the president and to kill Oswald. Our task was to seek evidence that might verify such a possibility.

Although the FBI had systematically wiretapped members of organized crime in the northeastern United States, they had not tapped crime figures in Dallas, New Orleans, or other areas where Ruby was known to have friends. Nor did the agency suggest to us that they might tap such people as part of our investigation.

Our investigation depended, therefore, upon circumstantial evidence. We looked at Ruby’s history and the associations he made. As a young man growing up in Chicago, he had known people associated with organized crime. He had been arrested, himself, for ticket-scalping. We could find no indication that, as a ticket scalper, he was anything but a freelance entrepreneur. Between 1937 and 1940, he was employed through the help of an attorney friend by Local 20467 of the Scrap Iron and Junk-Handlers Union. In 1939, his friend was murdered in a union power struggle. Employers who negotiated with the union said they had no indication that the union was connected with organized crime during that period.

After moving to Dallas in 1947, Ruby developed friendships with numerous figures associated with criminal activities. The FBI was unable to link any of those friends to the shooting of President Kennedy or to Ruby’s actions on November 24, 1963. What was most important to us in 1964 was whether friends or friends of friends had contacted him after President Kennedy was shot.

In 1977, the House Select Committee on Assassinations expanded on the Warren Commission’s investigation of organized crime by identifying numerous suspected members and leaders of organized crime who might have wanted to influence Jack Ruby before and after Kennedy was killed. It found that, on the night of November 21, Ruby and his business partner, Ralph Paul, had dinner in Dallas at the Egyptian Lounge (owned by reputed organized crime leader Joseph Campisi). A week or so after being arrested, Ruby placed Campisi’s name on a list of people who he asked Sheriff Bill Decker to call and to request a visit. After that request, made by Decker by phone, Campisi visited Ruby in jail while a deputy sheriff was present. Later, Campisi attended part of a day of Ruby’s trial.

The Select Committee produced no evidence that those visits were other than social. After an extended investigation of Ruby’s friendships with participants in organized crime, the Committee could make no finding that Ruby was involved in a conspiracy either to assassinate the president or to kill Lee Oswald.

The best assessments of Ruby’s association with organized crime may come from law enforcement officials in Dallas who knew Ruby. One was given to the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1978 by Dallas Police Lt. Jack Revill. In 1963 and 1964, he was in charge of keeping a watch on organized crime in Dallas. He told the Select Committee that, “if Jack Ruby was a member of organized crime, then the personnel director of organized crime should be replaced.” Bill Alexander, the chief assistant prosecutor in the trial of Jack Ruby, had a personal view of how Ruby came to murder Oswald.

Through his prosecution of Ruby, Alexander had come to know Ruby well. Thirty years after securing Ruby’s conviction, Alexander told the author Gerald Posner, “People that didn’t know Jack Ruby will never understand this, but Ruby would never have taken that dog with him and left it in the car if he knew he was going to shoot Oswald and end up in jail. He would have made sure that dog was at home with (his roommate) and well taken care of.” Ruby’s own testimony to the Warren Commission seems to support Alexander’s contention of a sudden decision: “... Sunday morning ... I saw a letter to Caroline (the president’s daughter) ... The most heartbreaking letter ... alongside that letter ... it was stated that Mrs. Kennedy may have to come back for the trial of Lee Harvey Oswald.... I don’t know what bug got ahold of me.... I am taking a pill called Preludin.... I use it for dieting. ... I think that was a stimulus to give me an emotional feeling that suddenly I felt, which was so stupid, that I wanted to show my love for our faith, being of the Jewish faith ... suddenly the feeling, the emotional feeling came within me that someone owed this debt to our beloved president to save Caroline the ordeal of coming back. I don’t know why that came through my mind.”

That was the explanation Jack Ruby would have given if he had testified at his trial. It was the defense his first lawyer, Tom Howard, preferred. It was a human, emotional defense. Ruby told one of his subsequent lawyers, Joe Tonahill, “Joe, you should know this. Tom Howard told me to say that I shot Oswald so that Caroline and Mrs. Kennedy would not have to come to Dallas.” It was not a false defense, however, for Ruby had mentioned his concern for Mrs. Kennedy even before talking to Howard.

Ruby’s conduct after he left his apartment on Sunday morning seems to support prosecutor Alexander’s assessment. Besides his dog Sheba, Ruby had also taken his portable radio downtown. From that, he could learn whether Oswald had been moved to the county jail.

If he should shoot Oswald, Sheba could be rescued. At the same time, Ruby’s car could not be moved without a tow truck. If he succeeded, the $2,000 in his pocket might be enough for bond and release from jail. If he needed more, he could direct his lawyer to the additional cash in his trunk. Most important, he would be a hero.

But he might not gain access to Oswald. Killing Oswald at the police station was problematic. No one, except the law enforcement officers who were interviewing Oswald, knew when Oswald would be moved. As the prosecutor observed, Ruby’s first obligation would have been to Sheba. His next obligation was clearly to send a money order to Little Lynn. Shooting Oswald seemed to come third.

In any event, were those the actions of a grand conspirator—especially one recruited by organized crime? Indeed, was Ruby planning to shoot Oswald ever since Friday night, as Sergeant Dean had testified at the Ruby trial? Was it a last-minute decision based on an unplanned opportunity, as prosecutor Alexander suggested? Was it a thought that arose only when Oswald came into sight—a psychotic episode, as Ruby’s trial attorney Melvin Belli claimed? Or was it the result of emotions that had built up over two days and, as Ruby himself told the Warren Commission, a decision that was made Sunday morning in order to spare Mrs. Kennedy the emotional trauma of returning to Dallas—and to show the world that a Jew had guts, as he said when he was arrested?

None of us can be certain. I have never believed that his concern about Mrs. Kennedy was the driving force for Ruby. With the passage of time, the gathering of more information, and further reflection, I have become satisfied that his acute fear of anti–Semitism, his fury at Oswald for killing the president, and his desire for acclaim were Ruby’s primary motivators.

Every friend and stranger we interviewed gave remarkably similar descriptions of Ruby in those hours between when he learned that the president had been shot and when he gunned down Oswald. Consistently, those people described a general state of agitation and a growing obsession with the Weissman ad; a belief that the ad was connected to the shocking murder of the president; his fear that Jews would be blamed for the assassination; and a belief, as Ruby himself said, that, if the world saw that “a Jew had guts,” Jews would be absolved of blame for President Kennedy’s death.