In September 1862, the South hoped to end the war by invading Maryland just before the mid-term elections. But its hopes were dashed after the bloodiest day in American history.

-

September 2022

Volume67Issue4

Editor’s Note: Justin Martin is the author of five books, including A Fierce Glory: Antietam —The Desperate Battle That Saved Lincoln and Doomed Slavery, from which he adapted this essay.

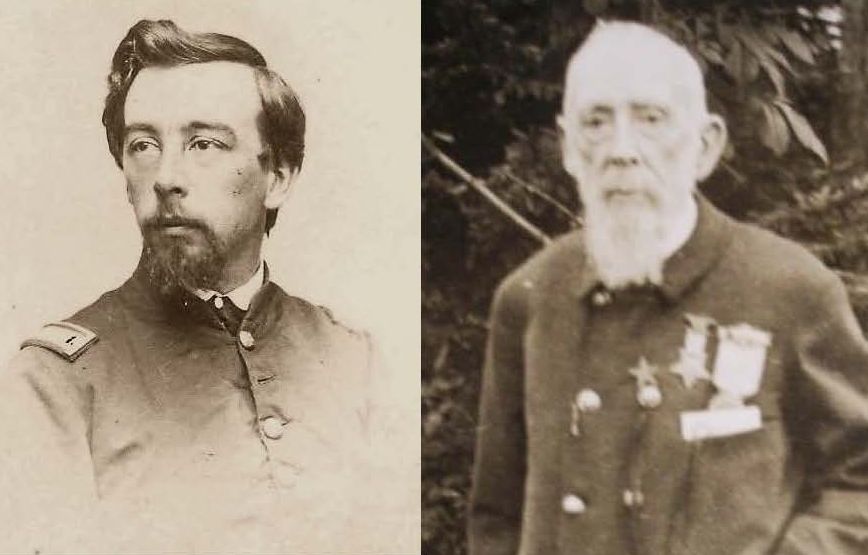

John Mead Gould spent a single day at Antietam. The battle consumed him for the rest of his life.

On September 17, 1862, Gould fought on the Union side as a lieutenant with the 10th Maine. Pandemonium reigned in the close confines of the Western Maryland valley where the battle took place.

So many soldiers fired so many weapons with such urgency that the field was soon thickly shrouded in smoke, and the air swam with projectiles, seemingly coming from all directions.

The sheer volume of noise was overwhelming. Cannon rumbled; bullets zinged. There were the shrieks of falling men, the whinnies of falling horses.

Antietam was more intense by far than anything Lt. Gould had ever experienced. It would continue to hold that grim distinction, though he’d fight in many subsequent battles until the end of the Civil War. Antietam was simply different from other contests: more heated, more savage, more consequential.

The battle occurred during an especially demoralizing stretch for the Union, filled with military losses, one coming fast on another. The Confederacy had grown increasingly bold, to the point of marauding into Maryland.

This was the war’s first Southern incursion into Northern territory. Achieve victory here, and the Rebel army could storm across Union territory and strike who-knows-where — Philadelphia, Baltimore, even Washington, D.C. No place would be safe. “Jeff Davis will proclaim himself Pres’t of the U.S.,” wrote a panicked New Yorker. “…The last days of the Republic are near.”

Even if an attack on a major city didn’t immediately follow, a Confederate victory promised to spark a political disaster. The Southern plan was to sow chaos and more chaos, and some of the ploys were remarkably subtle. For example, a Union loss at Antietam might prompt skittish Northerners to vote Lincoln’s Republican party out of Congress. In would sweep the Democrats, a politically conservative party at the time that might be more amenable to a negotiated settlement of the war. Perhaps a Democrat-controlled Congress would bypass Lincoln, recognizing the Confederacy’s independence.

Or maybe the states that had seceded would be invited to re-enter the Union with slavery intact. It’s no accident that Antietam happened in September. A primary goal was to disrupt the Union’s mid-term elections, only weeks away.

The Northern invasion had other enticements, as well. There was the possibility of luring Maryland into the Confederacy, That’s why it had been targeted in the first place. Maryland was a border state, one that had remained in the Union but with slavery intact. Southern sympathy ran high there. Score a victory not only on Union soil, but in Maryland, and perhaps it would unleash that pent-up Rebel sentiment. Maybe other teetering border states (Missouri, Kentucky, Delaware) would follow. The Confederacy’s territory would increase, as would its chances of winning the war.

A Southern victory at Antietam was also almost sure to invite foreign meddling. Across the Atlantic, both England and France were carefully monitoring the progress of the war. One more Union loss and they stood prepared to step in and serve as mediators to broker a separation between the warring parties. Some English leaders secretly thrilled at the notion that the former colony was so incapable of self-government that it had slipped into fratricidal warfare. From a more practical standpoint, both England and France had territorial ambitions that would be well served by replacing a single strong nation with a pair of smaller, weaker ones.

By invading Maryland, the Confederacy had cooked up a diabolically clever scheme. Victory at Antietam promised to open a number of different routes to the same outcome: an end to the war, substantially on Southern terms.

But Abraham Lincoln had a secret plan, shared only with a handful of his close associates and members of his cabinet: the Emancipation Proclamation. The document was filled with words like “aforesaid,” “thenceforward,” and “promulgated,” strange from a man who was capable of soaring rhetorical grandeur, a man who could summon “better angels” and sound “mystic chords of memory.” Lincoln was a lawyer by training; his proclamation was first and foremost a carefully crafted legal document, designed to grant freedom to the Confederacy’s slaves. He kept it in a pigeonhole in his desk at the White House, tinkering with it periodically, a work in progress.

Were it to be issued, Lincoln expected his proclamation to serve as a beacon, prompting enslaved people to escape, drawing them northward. Slaves worked the fields, growing the food that fed the Confederate army; they worked in factories, making the munitions essential to its success. The proclamation also included a first-ever invitation to African Americans to join the Union army.

Thus, the document promised to bolster the Union’s chances, even while it hobbled those of the Confederacy. As an additional draw, the proclamation promised to invest the Union war effort with a new and nobler purpose (ending slavery) at a time when Northern commitment had started to wane. Secreted away in that White House pigeonhole, Lincoln had a ready answer to the South’s invasion, one that promised to confer equal benefits on the North.

But victory was needed. After all, Lincoln couldn’t very well declare the Confederacy’s slaves free following another loss. William Seward, the Secretary of State, had counseled the president that such a gambit would merely be viewed as “our last shriek on the retreat.”

Clearly, the winning side at Antietam stood to transform its prospects. The stage was set for an epic showdown.

And now to the battlefield: Across a rolling valley, just east of the little town of Sharpsburg, Union commander George McClellan confronted his Confederate rival, Robert E. Lee. The Federals fielded a force of 55,000 versus about 35,000 Rebels, a near 2:1 advantage. For someone as wily as Lee, however, relative troop strength was just a number. He was content to be improvisational – very much his style. If McClellan overcommitted on some part of the field, Lee could exploit the mistake. A short way behind the Confederate battle line flowed the Potomac. If things became dire, the river would serve as the emergency exit. Lee’s troops could cross to the safety of Virginia.

Meanwhile, ever-cautious McClellan hatched an actual battle plan. He intended to simultaneously press the top and bottom of Lee’s battle line, squeezing his troops, as if in a vise. Once the Confederates were compacted and confounded, he’d strike the center. This would be like a hard punch to the nose, a knockout blow. McClellan’s plan would prove deceptively unsimple.

The battle commenced at 5:45 AM, first light. John Gould and his 10th Maine were involved in the opening action, attempting to press down on the Rebels at the Northern reaches of the battlefield. His regiment was part of the upper jaw of the vise. But things did not go as planned. In a matter of minutes, a quarter of Lt. Gould’s regiment (71 of 277 men) went down, wounded or killed. “It was very easy to die that day,” he would recall.

General Joseph Mansfield staggered past, his coat flapped open, revealing a crimson bloom spreading across his abdomen. Gould helped him from the field. The general soon slipped out of this world. He’d be one of six major generals killed at Antietam, three from each side.

McClellan’s battle plan was one of the day’s first casualties, felled by the reality, the chaos, of war. Federal forces struck the Confederate center, delivering that punch to the nose prematurely. As it happened, the Rebel center had one of the strongest positions on the field, a stretch of road worn down by wagon traffic, wind, and rain. In certain spots, this ancient byway ran four feet below the surrounding terrain. The graycoats had piled stones and broken fencing in front of this sunken road, fashioning a formidable redoubt.

Wave upon wave of Federals slammed into this position, attempting to dislodge the dug-in Rebs. One Union officer observed that the dead soon lay so thick that it would have been possible to walk for one hundred yards, stepping only on bodies, never touching the earth. For posterity, the sunken road would be rechristened the Bloody Lane.

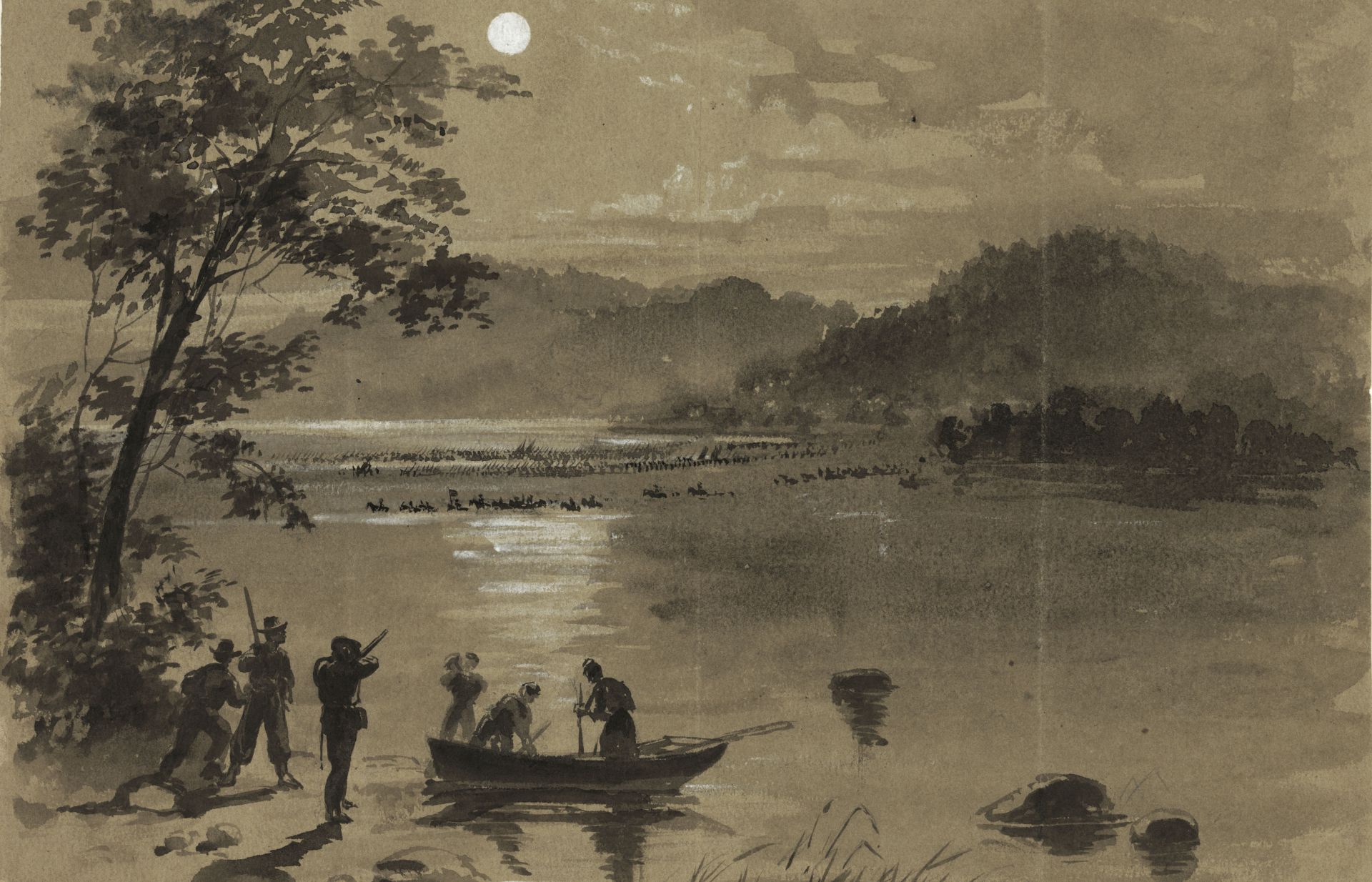

Meanwhile, Union forces at the Southern reaches remained at a standstill for hours. In other words, the vise’s bottom jaw, rather than relentlessly tightening, hung slack. But these troops had drawn an especially difficult assignment. They were tasked with crossing Antietam Creek under withering fire from the Rebs on the bluffs on the other side. When they finally got across, it was midday.

The Union forces regrouped. What was now required was climbing three-quarters of a mile up a steep hillside under a ceaseless, savage cannonade. If the Federals could reach the top, they could pour into Sharpsburg and cut off Lee’s vital exit route across the Potomac. Yes, it was still possible to destroy the Confederacy in time for dinner.

But just as the bluecoats began to reach the crest, as they prepared to spill into Sharpsburg, at the last available moment — in one of the most famous episodes of the war — A.P. Hill, one of Lee’s most trusted generals, arrived, 2,500 fresh soldiers in tow, following a seventeen-mile march from Harpers Ferry. These newcomers drove the Federals back down the hillside. All the way back to the banks of Antietam Creek.

The sun began to set. A battle that had started at first light now came to a close — a draw.

The next night, Lee’s hard-used, bedraggled army crossed the Potomac into Virginia. This Northern invasion was over. Union cities were safe from the Rebel hordes — for now. Though a tactical draw in strict military terms, the battle was an optical victory from the standpoint of Northern sentiment.

Lincoln seized the opportunity. Five days after Antietam, he issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, giving the states in rebellion one hundred days to lay down their arms and rejoin the Union. When that didn’t happen, he would issue the final document on January 1, 1863, officially freeing the Confederacy’s slaves and changing the course of the war.

Antietam’s carnage was staggering. Over the course of a single day — still the most lethal in American history — the official combined death toll for Union and Confederate forces was 3650. This dwarfed everything that had come before. Such landmark Revolutionary War battles as Saratoga and Yorktown routinely resulted in fewer than 100 deaths among the Colonials. The entire War of 1812 (which, belying its name, stretched over nearly three years) involved 2,200 U.S. combat fatalities, a lower number than occurred during a mere twelve hours at Antietam. Even days of infamy such as Pearl Harbor and September 11 saw fewer Americans killed.

Antietam’s grim toll would have been even higher had it not been for Jonathan Letterman, the Union doctor-in-chief. The battle was the first genuine test of his ideas about how to deliver faster, better care to wounded soldiers. This was also the first engagement in which Clara Barton was able to realize her ambition of going directly to the treacherous front lines to treat soldiers. For her heroism at Antietam, she earned the sobriquet that would stick with her for the rest of her life: “Angel of the Battlefield.”

Meanwhile, Alexander Gardner took a series of photographs that was nothing short of revolutionary, expanding the art form, forever changing the way the public perceived warfare. Gardner’s photos of the dead at Antietam were widely circulated in the North. At a time when the public’s conception of warfare was mostly confined to romanticized magazine illustrations of brave soldiers in neat uniforms proudly flying the flag, Gardner’s images — stark, brutal, haunting — had the force of revelation. So, this was what was happening on those faraway fields? And with that realization came a corollary question: If men were dying, shouldn’t their sacrifice be in service of a worthy purpose, a truly glorious cause? In this way, Gardner’s photos worked in tandem with Lincoln’s proclamation.

Indeed, as America’s bloodiest day, as a battle with massive military and political stakes, as a crucible for bold new innovations, as a watershed event involving such towering figures of the age as Lincoln and Lee, as the occasion for the Emancipation Proclamation — for all these good reasons — Antietam was a more critical battle than Gettysburg. Yes, Gettysburg receives more glory. Lee’s second incursion into the North was a marathon three-day contest that broke the Confederacy. After Gettysburg, the Rebels never again posed a substantial offensive threat, never really recovered, though the Civil War would stagger on for another two years.

However, the case for Antietam is simple and irrefutable. Had its outcome been different, there would have been no Gettysburg.

As for Lt. Gould, after the war, he went back to his hometown of Portland, Maine. Before enlisting, he’d worked as a bank teller. He returned to his old job and remained in it for the rest of his working life, receiving a single promotion—to cashier. Along the way, Gould got married and raised three children. He taught in a Sunday school and amassed a curious collection of buttons. Antietam was never far from his thoughts.

He wrote letters to his fellow Union veterans, seeking to plumb their memories, hoping to resolve lingering mysteries. Which enemy regiments had fired on his Maine boys on that fateful day? What were the exact spots where his various comrades went down? Where did General Mansfield fall?

As the years passed, old hostilities faded away. Gould began to write to his one-time adversaries. Regarding Antietam, he found them even more expansive than his Union comrades. “Confederates were better correspondents,” he noted. Gould made repeated visits to the battlefield, sometimes even walking the grounds in the company of graying former Rebels. On one visit, he “snapped a little Kodak,” a testament to changing times, the passage of the years. On another visit, he stayed for an entire week, ceaselessly walking the field, trying to make sense of that now-distant day.

Some mysteries he did manage to solve. He grew confident that he had identified the precise spot (near a distinctive boulder) where General Mansfield fell. Other questions would dog him to his grave: “Those things make me lie awake at night.”

Gould passed away on January 1, 1930, aged ninety, at his house on Pearl Street, the same one where he’d lived as a boy. For nearly seven decades since the battle, the events of Antietam had never been far from his mind.

As we pause to reflect, during another September, 160 years later, perhaps the same holds true for our fractious nation. Antietam has never left us.