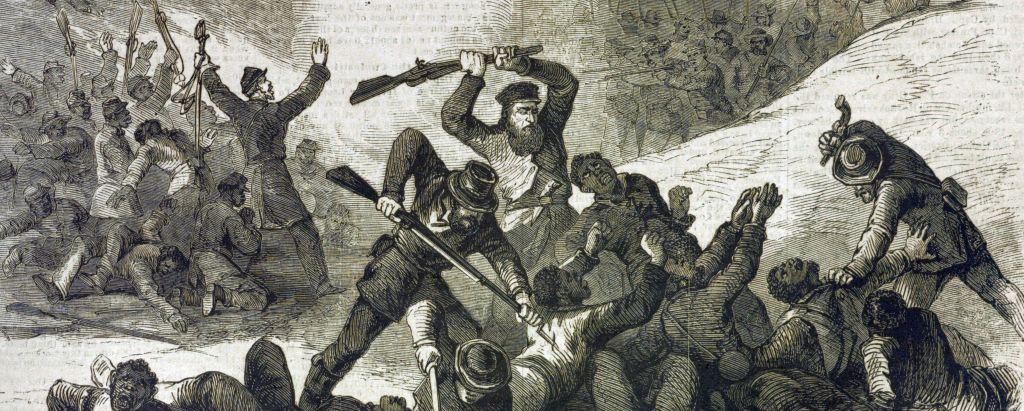

The brutal murder of hundreds of African-American soldiers at Fort Pillow had a profound effect on Northern sentiment during and after the Civil War.

-

November/December 2021

Volume66Issue7

Editor’s Note: Fergus M. Bordewich has written eight books of history. Portions of this essay were adapted by the author from his most recent book, Congress at War: How Republican Reformers Fought the Civil War, Defied Lincoln, Ended Slavery, and Remade America.

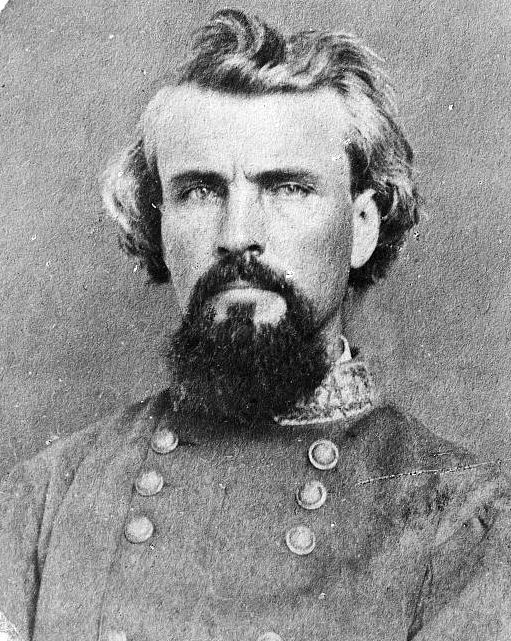

On April 12, 1864, a hard-riding Confederate force of between 1500 and 2000 cavalry under General Nathan Bedford Forrest, a wealthy prewar slave trader and the South’s most enterprising and skillful cavalry commander, surprised the garrison of Fort Pillow, 40 miles north of Memphis.

Forrest, goateed and gimlet-eyed, was known to Confederates and Federals alike for bold strikes and a knack for seizing decisive victories against overwhelming numbers of the enemy. At Fort Pillow, however, numbers were on Forrest’s side. The attack came at the climax of a daring raid that had taken Forrest’s men deep inside Union lines through Tennessee and Kentucky as far as Paducah, close enough to Illinois to stir panic north of the Ohio River.

ever perpetrated on American soil

outside of the Indian wars.

Fort Pillow was a complex of earthworks and gun emplacements sprawling along bluffs overlooking a bend in the Mississippi River, on the western edge of Tennessee across from Arkansas. Built by the Confederates in 1861, it was captured by the Union the following year. Its river-facing defenses were formidable, but the handful of poorly situated field guns and howitzers that were meant to protect the landward side overlooked a maze of deep gulches that blocked the defenders’ view. The garrison included a total of about 550 men from two black artillery units, and a white Unionist regiment of Tennessee Cavalry.

Forrest, whose reputation for ruthlessness preceded him, warned the defenders that he wouldn’t be responsible for what happened to them unless they surrendered immediately. Then, under the cover of a white flag, he infiltrated men through the gulches until they were immediately beneath the fort.

The attack was ferocious, the defense chaotic. The broken land made it difficult, and soon impossible, for men from one part of the garrison to help those who were overrun. A sniper’s bullet killed the fort’s commander, and the white Tennesseans broke and fled. Most of the blacks resisted spiritedly until they were overwhelmed. The end was swift and horrific.

Forrest’s Confederates cried, “No quarter!” and “Black flag!” — that is, take no prisoners. Soldiers, whites as well as blacks, who tried to surrender were shot, hacked with sabers, and beaten to death with rifle butts. Wounded men were murdered where they lay. Several were burned to death in huts. Others were thrown into pits with the dead and buried alive. Fleeing men slid, fell, and jumped over the edge of the bluff. Many threw themselves into the river in an attempt to save themselves. Some drowned, but many others were picked off by Confederate riflemen firing at leisure from shore.

Confederates had murdered black Union soldiers before, but nothing approached the scale of butchery at Fort Pillow. News of the slaughter reached the North within hours by telegraph. Four days after the massacre, the Senate voted to immediately dispatch Sen. Benjamin Wade of Ohio and Rep. Daniel Gooch of Massachusetts, who served on the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, to interview eyewitnesses.

At Cairo, Illinois, a shaken brigadier urged them to publish what they learned as quickly as possible before “bad men, who sympathize with the rebellion ... deny the facts.” His concerns were not exaggerated. He handed Wade a clipping from that day’s Cairo Daily Democrat, a Copperhead sheet, which claimed that no atrocities at all had occurred and scoffed at “extravagant stories” as government propaganda.

From Cairo, Wade and Gooch continued south via Columbus, Kentucky, to Fort Pillow. The testimony they recorded still makes harrowing reading. They found bodies with gaping wounds, some bayoneted through the eyes, some with skulls broken through, others with their bowels ripped out.

“We saw bodies still unburied of some sick men who had been fleeing from the hospital and beaten down and brutally murdered, and their bodies left where they had fallen. We could still see the faces, hands and feet of men, white and black, protruding out of the ground.”

A white hotel keeper told them that he saw the Confederates trap about one hundred soldiers at the bottom of the bluffs along the river. When they begged to be allowed to surrender, “The rebels would reply, ‘God damn you, why didn’t you surrender before?’ and shot them down like dogs.”

John Hogan, a Negro corporal, testified that he saw Forrest’s men confront a Captain Carson, a white officer: “They asked him how he come to be there, and then asked if he belonged to a nigger regiment, and then they shot him.”

Several witnesses saw Lieutenant Akerstrom of the 13th Tennessee crucified against the side of a building that afterward was set on fire. Several black soldiers were also nailed to the floor of the same building. Others were lined up and shot while holding white handkerchiefs in their hands as tokens of surrender. A white lieutenant testified that he saw several black soldiers murdered as they lay wounded: “As they were crawling around, the secesh would step out and blow their brains out.” Another white cavalryman, James Walls, testified, “I saw them make lots of niggers stand up, and then they shot them down like hogs.” At least two women and three small black boys were shot and then beaten to death.

Woodford Cooksey, a white soldier who had been shot while lying unarmed on the ground, watched the Confederates murder three whites and seven blacks the morning after battle. “I saw one of them shoot a black fellow in the head with three buck shot and a musket ball,” Cooksey said. “The man held up his head, and then the fellow took his pistol and fired that at his head. The black man still moved, and then the fellow took his saber and stuck it in the hole in the negro’s head and jammed it way down, and said, ‘Now, God damn you, die!’ The Negro did not say anything, but he moved, and the fellow took his carbine and beat his head soft with it.”

Forrest initially reported to his superiors that he had killed more than 450 of the enemy and suffered just twenty killed and sixty wounded from his own command. He wrote, “It is hoped that these facts will demonstrate to the Northern people that the Negro soldier cannot cope with Southerners.”

Of the 585 Union soldiers at the fort, at least 277 were killed, an astronomical death rate of 48 percent unmatched in any other battle of the war; of these, white soldiers were killed at a rate of 31 percent and blacks at a rate of 64 percent. Of the 269 black soldiers, 195 were killed, as well as an indeterminate number of black civilians.

Although the Confederate authorities later tried to play down the barbarism of what Forrest had done, the worst was corroborated by a Confederate cavalryman, Achilles V. Clark, who wrote to his sisters: “The poor deluded negroes would run up to our men fall upon their knees with uplifted hands scream for mercy but they were ordered to their feet and then shot down. The white men fared but little better. Blood, human blood stood about in pools and brains could have been gathered up in any quantity.”

The 128-page report that Wade penned in a feverish burst of anger on his return to Washington ranks among his most significant contributions to the entire war effort. Making the case that the rebels had clearly adopted a policy of systematic savagery against black troops, Wade wrote, “the testimony herewith submitted must convince even the most skeptical that it is the intention of the rebel authorities not to recognize the officers and men of our colored regiments as entitled to the treatment accorded by all civilized nations to prisoners of war.”

Distributed nationally in a print run of forty thousand copies, and widely cited in newspaper articles, the report helped build appreciation for the sacrifices of black volunteers and support for the vital legislation that would create civil rights for former slaves by awakening the Northern public to the unique risks that faced black volunteers, and more broadly to the barbarism that festered at the heart of racism. While the report was not sufficient by itself to transform Northern feelings toward blacks, it helped to create a constituency that would support the Radicals’ drive toward general emancipation and eventually full civil rights.

The Fort Pillow massacre in the spring of 1864 demonstrated beyond any argument the savagery that would be visited upon blacks who defied the South’s unforgiving strictures of race. It also underscored in blood the uncertain postwar fate of the South’s nearly four million slaves, if Union victory succeeded in freeing them. A problem that had once seemed the preserve of ideologues now needed to somehow be solved, practically and permanently.

For more than a year Congress had inconclusively debated what Reconstruction was to be. On what terms, and in what form, would seceded states be permitted to rejoin the Union? Should Reconstruction be punitive or forgiving? What role, if any, would government play? Who would decide? Congress? The president? Southern whites? How it was implemented would profoundly influence the lives not only of the freedmen, but also of many millions of Southern whites for whom the prospect of Negroes as anything but slaves was unimaginable.

The crafters of the platform the Republicans adopted at their national convention in 1864 in Baltimore tried hard to satisfy the Radicals. It was firmly emancipationist: no compromise with the rebels, no terms of peace except unconditional surrender, and the “utter and complete extirpation [ of slavery] from the soil of the American republic” by means of constitutional amendment. Clearly with the Fort Pillow massacre in mind, the platform also declared that the government owed every soldier “without regard to distinction of color” the full protection of the laws of war, and that any rebels who transgressed the “usages of civilized nations” must be appropriately punished. Not insignificantly, even within sight of the enemy.

Without the Congressional investigation, the Fort Pillow massacre — the worst war crime ever perpetrated on American soil outside the Indian wars — might well have been scrubbed from historical memory.