Representatives objected to Tyler’s vetoes, arguing that the president should be “dependent upon and responsible to” Congress.

-

February/March 2021

Volume66Issue2

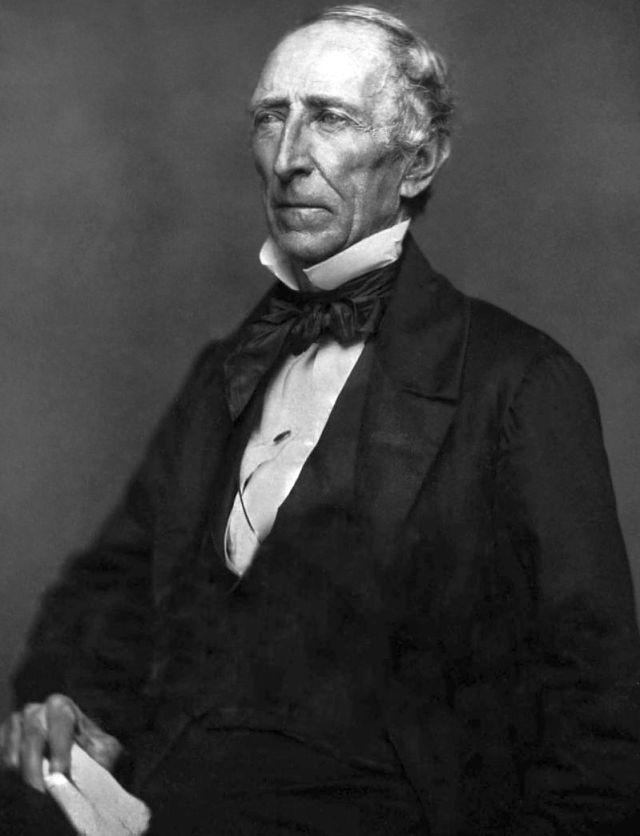

The Whig Party came to power in 1841 behind William Henry Harrison, but Harrison died one month after assuming office. He was succeeded by Vice President John Tyler of Virginia, who thereby became not only the first man to attain the office under those circumstances but also the nominal head of the Whig Party. He quickly broke with the party, however, by vetoing the heart of its economic program. In September, 1841, all but one member of his cabinet resigned in unison, and a congressional Whig caucus read him out of the party.

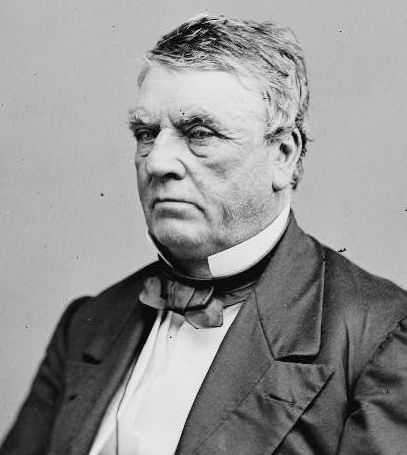

Over the next couple of years, Tyler had a contentious relation with Congress, sometimes refusing to cooperate. In 1842 Tyler returned his fourth veto of a major Whig economic measure. Rather than placing the veto message on the record, the House appointed a select committee headed by former president John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts and John Minor Botts of Virginia to report on the veto.

The committee’s majority report vented the accumulated frustration of the long-suffering Whigs. The Constitution, it insisted, made the president “dependent upon and responsible to” Congress, yet Tyler’s vetoes had nullified “the whole action of the Legislative authority of this Union.”

The committee charged that Tyler had formally pledged to a congressman that he would sign an earlier bill and then had violated the pledge by vetoing the measure. It criticized as “anomalies of character and conduct rarely seen upon earth” Tyler’s “effusions of temper and sentiment divulged at convivial festivities,” his obtrusion “upon the public eye by the fatal friendship of sycophant private correspondents,” and his usurpation of legislative and judicial power, by which it apparently meant the vetoes.

The committee’s majority, the report stated, thought Tyler’s actions merited invocation of the impeachment process, but they did not recommend it because impeachment would fail at that time. By a vote of 100-80, the House accepted this report with its implications that Tyler had indeed committed impeachable offenses.

Tyler responded with a formal protest to the House on August 30, 1842. Using language not found in the report itself, he accused the committee of “Arraign[ing]” his motives, “assail[ing] [his] whole official conduct,” and charging him with impeachable offenses without impeaching him. The House must impeach him, protested Tyler, if it was willing to vote him guilty of such offenses, so he could defend his honor in a Senate trial.

Denying the truth of any of the charges, Tyler seemed to concur with the committee that if they were true, he deserved both impeachment and removal from office:

Tyler, that is, agreed that duplicity, lying to Congress, was grounds for conviction.

To Tyler’s dismay, the House refused even to accept his protest and put it on the record. Instead, the House denounced the protest itself as a breach of House privileges. Nor had Tyler heard the last cry for impeachment.

The House vote in August to accept the critical Adams report provided the justification for John Minor Botts, a bitter foe of Tyler, to present in January nine formal articles of impeachment for “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Botts assailed as impeachable Tyler’s entire record in office.

His first six charges listed as abuses of power presidential prerogatives like appointments, removals, and the veto which had long been accepted as constitutional. The last three charges merit extensive quotation because they summarize so well what many congressmen considered misbehavior.

Little came of Botts’s articles of impeachment. On January 18, 1843, the House defeated his motion to appoint a committee to investigate them by a vote of 127-83. Tyler, therefore, never had to respond formally. But he did so indirectly in a message of January 31, 1843, when he finally answered the House request for information on War Department investigations of Cherokee frauds. While he sent in all the findings, he vigorously defended his earlier refusal to comply.

Tyler argued that his constitutional obligation to enforce the laws dictated his undertaking executive investigations, and those inquiries could succeed only if the information remained confidential. Citing the House’s previous acquiescence in his refusal to turn over patronage papers as implicit recognition of executive privilege, he specifically addressed the House resolutions limiting that privilege passed the previous August.

Tyler firmly denied that the House’s right to demand information meant that the president had to comply with such a demand or that any papers in the hands of the president or cabinet members “must necessarily be subject to the call of the House of Representatives merely because they related to a subject of the deliberations of the House.” “Certain communications” were “privileged,” and “the general authority to compel testimony must give way in certain cases to the paramount rights of individuals or of the Government.”

Tyler also took the opportunity to denounce the new law forbidding payment of presidential investigations without specific congressional authorization. That law, he protested, “virtually denied to the Executive” the power to undertake investigations of executive departments no matter how urgent the necessity or flagrant the abuse.”

Adapted from a longer essay which originally appeared in Presidential Misconduct: From George Washington to Today, edited by James M. Banner, Jr. Published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.