Rush was a visionary writer and reformer, a confidant to John Adams, Washington's surgeon general, and opponent of slavery and prejudice, yet he's not a well-known founding father.

-

Fall 2019 - George Washington Prize Books

Volume64Issue5

Excerpted from the George Washington Book Prize finalist Rush: Revolution, Madness, and Benjamin Rush, the Visionary Doctor Who Became a Founding Father, by Stephen Fried.

In the late morning of August 29, 1774, a well-worn carriage made its way down dusty King’s Highway, along the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River just below Trenton.

In the carriage were the four members of the Massachusetts delegation to the first Continental Congress—including John Adams, a scruffy, gregarious thirty-eight-year-old lawyer, who was extremely anxious about the future of his country. He had written to his wife, Abigail, the evening before about how it would feel to finally arrive in Philadelphia at the “Theatre of Action,” where he hoped that “God Almighty” would grant him and his colleagues “Wisdom and Virtue sufficient for the high Trust that is devolved upon Us.”

But Adams also had some less lofty concerns. After more than two weeks on the road during the sultriest time of the year, he was sweaty and stinky and in desperate need of clean clothes. He had six shirts, five pairs of stockings, two caps, a pair of worsted stockings, and one silk handkerchief awaiting a laundress the moment they got to town.

Their carriage soon arrived in the farm town of Frankford, five miles north of the city, where Adams and his group were to be met by a local delegation. They presumed these would be like-minded Pennsylvanians who believed in the cause of freedom from England and would laud their bravery; Massachusetts was, so far, the primary place where colonists and British troops had clashed. The delegation also included John’s older cousin Samuel, a leader of the Sons of Liberty, who had instigated the recent Boston Tea Party.

Instead, the Philadelphians, after exchanging pleasantries and bringing the New Englanders to a nearby apartment for drinks in a private room, proceeded to tell their guests the last thing they expected to hear.

“You must not utter the word ‘Independence,’ nor give the least hint or insinuation of the idea, neither in Congress or any private conversation,” Adams would later recall being warned. “If you do, you are undone.” If they wanted this historic meeting of colonies to make any progress, the Philadelphians insisted, they needed to shut up with all their open talk about liberty.

Their hosts also lectured Adams and his colleagues about strategy. While they were “the representatives of the suffering state” and might reasonably expect to speak loudest, the Philadelphians advised that “you must not pretend to take the lead.” Virginia, the largest colony, would be the key actor in bringing the southern and middle colonies into a union, and the Virginians would need to feel they were in charge. Adams and his colleagues had to suck it up and defer to them.

Perhaps more unexpected than the bold advice was that one of its loudest and most energetic proponents was the youngest and least known member of the welcome party: a twenty-eight-year-old physician named Benjamin Rush. He was one of the only people in the room who hadn’t been selected as a delegate to the historic Continental Congress. And the closest he was going to get to that historic meeting in Carpenters’ Hall was that every Tuesday at ten a.m. he and another young doctor gave free smallpox inoculations at the nearby State House.

But Benjamin Rush made quite a first impression. He was tall, lean, and handsome with active blue-gray eyes and an aquiline nose. His long blond-brown hair, tied back in a loose ponytail, accentuated his most prominent feature: an uncommonly large head. To some, the size of his skull bespoke “strength and activity of intellect,” while others viewed him as having a head overfull of ideas he couldn’t keep to himself.

Unlike the pedigreed doctors who had trained him in America, Scotland, England, and France, Dr. Rush was a medical and political prodigy from a middle-class family on the humbler side of Philadelphia. He had lost his father, a gunsmith, at the age of five, leaving him and his five siblings to be raised by their mother, who opened a package goods store and tavern just down the street from Benjamin Franklin’s print shop and post office.

But because of young Rush’s astonishing mind—besides total recall, he had what he referred to as the “peculiar happiness” of being able to synthesize and humanize disparate ideas into searing rhetoric—he had finished school at thirteen, graduated from the College of New Jersey (now known as Princeton) at fourteen, finished medical training in Edinburgh and London at twenty-two, and begun practicing and teaching medicine at twenty-three. He was still single in his late twenties because his family had convinced him it would be bad for his career to marry before thirty.

All John Adams knew about Rush at that moment was that the lanky doctor was spellbindingly sure of himself. He talked a lot. Yet it wasn’t quite clear where this promiscuously opinionated young fellow fit into this group of established lawyers and business leaders.

As they left the tavern, Rush managed to switch carriages so he could ride back to town with Adams and another Massachusetts delegate. Without his fellow Philadelphians around, he proceeded to fill in Adams on the local political gossip, warning him about citizens he would meet who might seem friendly enough to his cause but would, ultimately, remain committed to the Crown—because they were loyalists, pacifists, or haters of change. Rush seemed to understand people unusually well for a man so young, and his analysis moved easily from politics to religion to medicine to the calculus of liberty.

Adams listened and carefully asked questions. He did not completely engage with Rush, and the young doctor could sense it. Rush later described their first conversation as “cold and reserved.” And when Adams mentioned Rush for the first time in his journal, it was several weeks later, and only to comment about how good the food was when the doctor had him and other congressmen over for dinner. The melons especially were “fine beyond description.”

When they met that August day in 1774, Adams could not have imagined how important Benjamin Rush would become to him, to the revolution, and to the new nation—how this headstrong young man would become a Founding Father; a transformative writer and lecturer; and the nation’s most famous, powerful, and controversial physician, who knew his fellow patriots as intimate friends, rivals, and patients. But Rush would surprise Adams, as he did so many others.

Before the Continental Congress met, Rush was already a protégé of Benjamin Franklin—who provided introductions, once Rush finished medical school in Scotland, for the young doctor to dine with Enlightenment luminaries, including Samuel Johnson and David Hume.

Rush returned to America as one of four professors at the first medical school in the colonies. As a young writer and inconvenient truth teller, he had already made his mark on some of the social and political causes he would wrestle with throughout his life. Between medical publications, he had penned one of the boldest abolitionist pamphlets ever published, and had quietly co-authored the Philadelphia anti-tax proclamation the Sons of Liberty had adopted to justify the Boston Tea Party.

Energized by the contagious spirit of the congress, Rush went on to serve the revolution as a doctor, a politician, a social reformer, an educational visionary, and even an activist editor—when, in 1775, he convinced an unknown writer named Thomas Paine to write “Common Sense,” which Rush then edited, titled, and brought to a publisher. The doctor went from gleaning political gossip from dinner guests in 1774 to, after being elected to the Second Continental Congress in 1776 at the age of thirty, signing the Declaration of Independence. (He also married, after falling in love with seventeen-year-old Julia Stockton, the daughter of a fellow signer.)

He treated patients throughout the war, taking time off from Congress to triage troops. He crossed the Delaware that cold December night along with General George Washington’s forces, patched up shot and bayonetted soldiers on the bloody battlefields of Trenton and Princeton, and survived being briefly captured during the Battle of Brandywine. He went on to serve as a surgeon general and adviser to Washington, but he would eventually leave the war—and the government—over a political showdown that led to the court martial of a former mentor.

Before leaving, he penned a pamphlet that would transform military medicine in America and become a standard guide for soldiers and officers in too many wars, its opening line still resonant today: “Fatal experience has taught the people of America the truth . . . that a greater proportion of men perish with sickness in all armies than fall by the sword.”

At the age of thirty-two, Rush retreated to Philadelphia to navigate the limbo years after British occupation and the successful end of the war. There, as he and Julia raised a growing family, he came to understand that the American Revolution was not over at all—that in fact it had barely begun. His new nation would need more than a Constitution to thrive: it would have to define and encourage a new form of active, responsible citizenship. While building his medical career at America’s first hospital and first medical school, Rush also recommitted to politics and made it his mission to identify and champion the causes the American people would have to embrace to become what he called “republican machines”—upholders of the new democracy.

In a landmark speech delivered at the American Philosophical Society on February 27, 1786, Rush diagnosed the challenge of the newly united states. The struggle, he said, would be to balance “science, religion, liberty and good government.” He would spend the rest of his life trying to embody that balance, through writing, teaching, and the building of associations and institutions, amassing several careers’ worth of accomplishments.

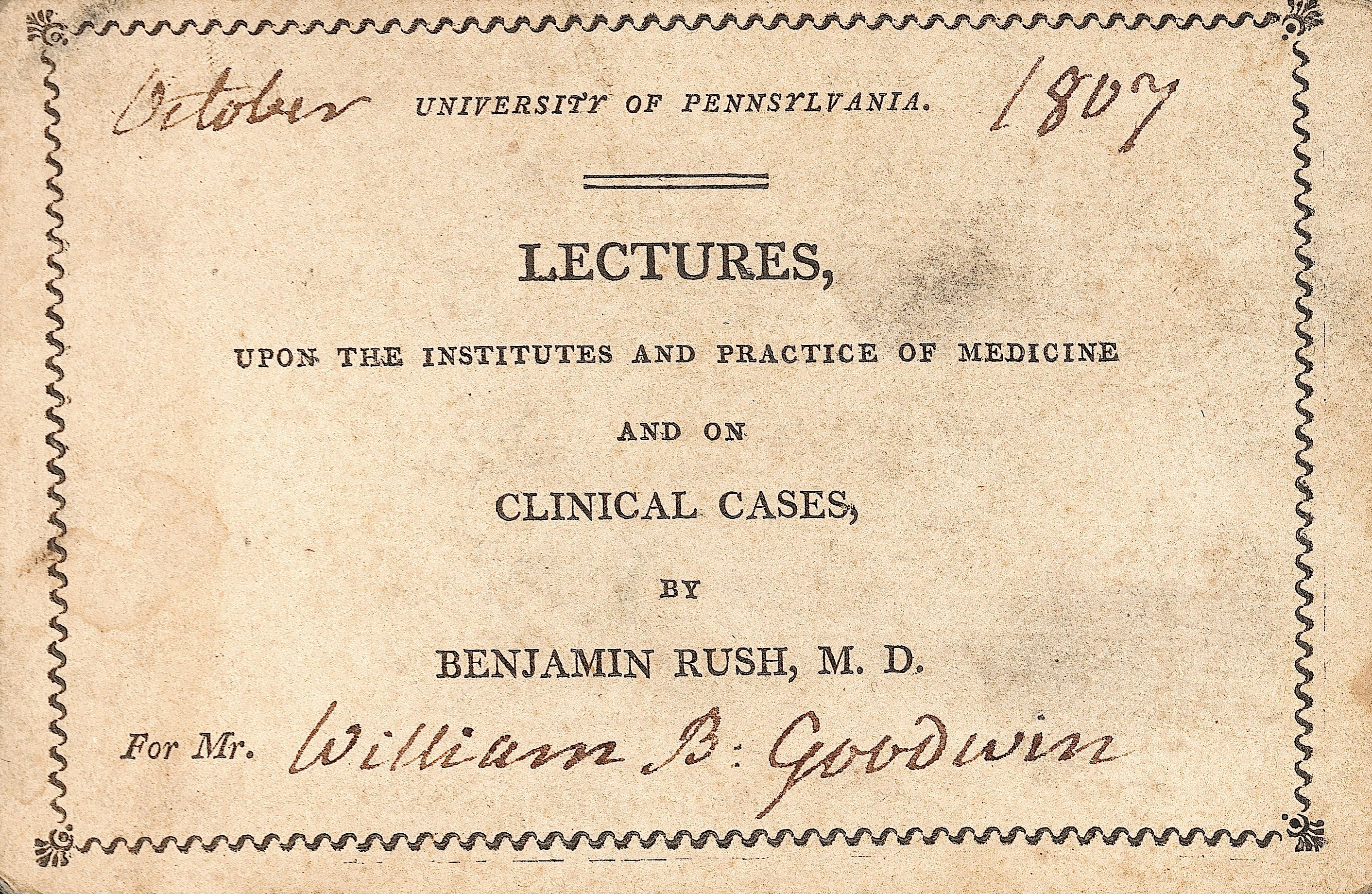

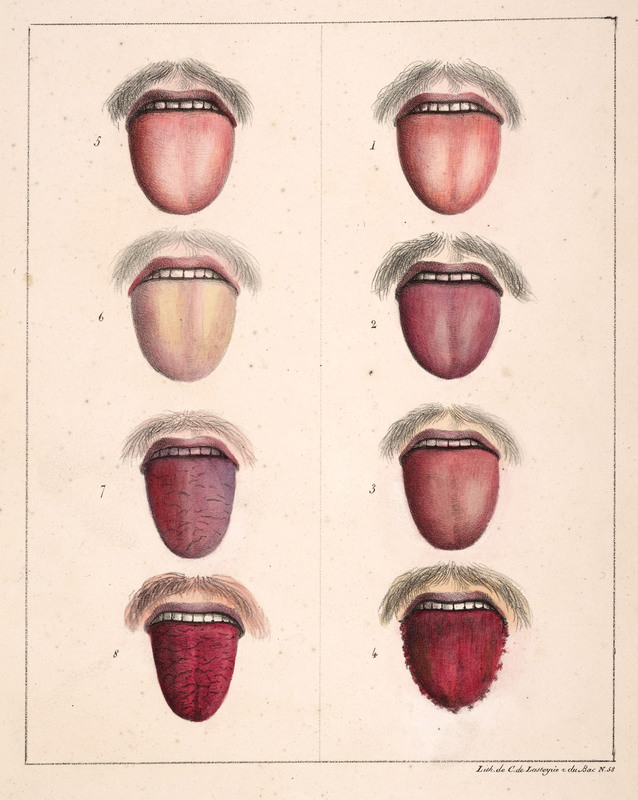

Over the next three decades Rush became the most prominent physician and public health advocate in America, and one of the few American public intellectuals whose writings were read in Europe. His 1786 speech also provided the groundwork for his most lasting contribution to medicine: fusing his ideas about equality and republicanism with clinical work, he declared that mental illness and addiction were medical conditions and deserved to be treated as such. At Pennsylvania Hospital he enacted this philosophy, laying the foundation for the development of psychiatry, clinical psychology, and addiction medicine.

Outside the hospital, Rush became the nation’s loudest advocate for public schooling, helping open education to women, to African Americans, and to non-English-speaking immigrants. He founded the nation’s first rural college, Dickinson, in far-off central Pennsylvania. He also rejoined the abolition movement and the battle against racial prejudice. Defying public opinion and Philadelphia’s religious establishment, he helped young African American clergymen found and fund two of the nation’s first churches led by and for black worshippers.

Rush played a key role in the ratification of the U.S. Constitution; though a man of deep faith himself, he was one of the nation’s first resonant voices to argue for the separation of church and state, and for the protection of religious liberty.

As the U.S. Capitol returned to Philadelphia in 1790, just after the death of its most beloved native son, Franklin, Rush did his best to become the nation’s next Benjamin.

In the following years, he grew closer to Presidents Adams and Jefferson, along with other founders in the new government, who came to rely on Rush for medical care, intellectual stimulation, and the best local gossip. In private and public he wrote with expanding breadth and sometimes humor. Adams loved Rush’s rants on issues such as American materialism (“We are indeed a bebanked, and a bewhiskied & a bedollared nation”) but also knew the doctor had been keeping notes for years about revolutionary personalities and intrigues, including spot-on sketches of every signer and important military leader. (Rush’s three-word assessment of himself in his founding father burn book: “He aimed well.”)

Yet, after years in the new American spotlight, both Rush and Philadelphia were nearly destroyed by the most horrific medical crisis in the history of the new world: the 1793 yellow fever epidemic. Rush, among a handful of prominent doctors who didn’t flee the city, became a public health hero to many, though also a villain to those who considered his high-dose purges and bloodletting to be less heroic than extreme. While his wife and children were sent away for their safety, his sister, Rebecca, stayed to take care of him. She died of yellow fever, as did several of his apprentices and many of his friends. He narrowly escaped death himself.

In just three months, almost 10 percent of the capital’s population was lost. Neither the country nor Dr. Rush would be quite the same.

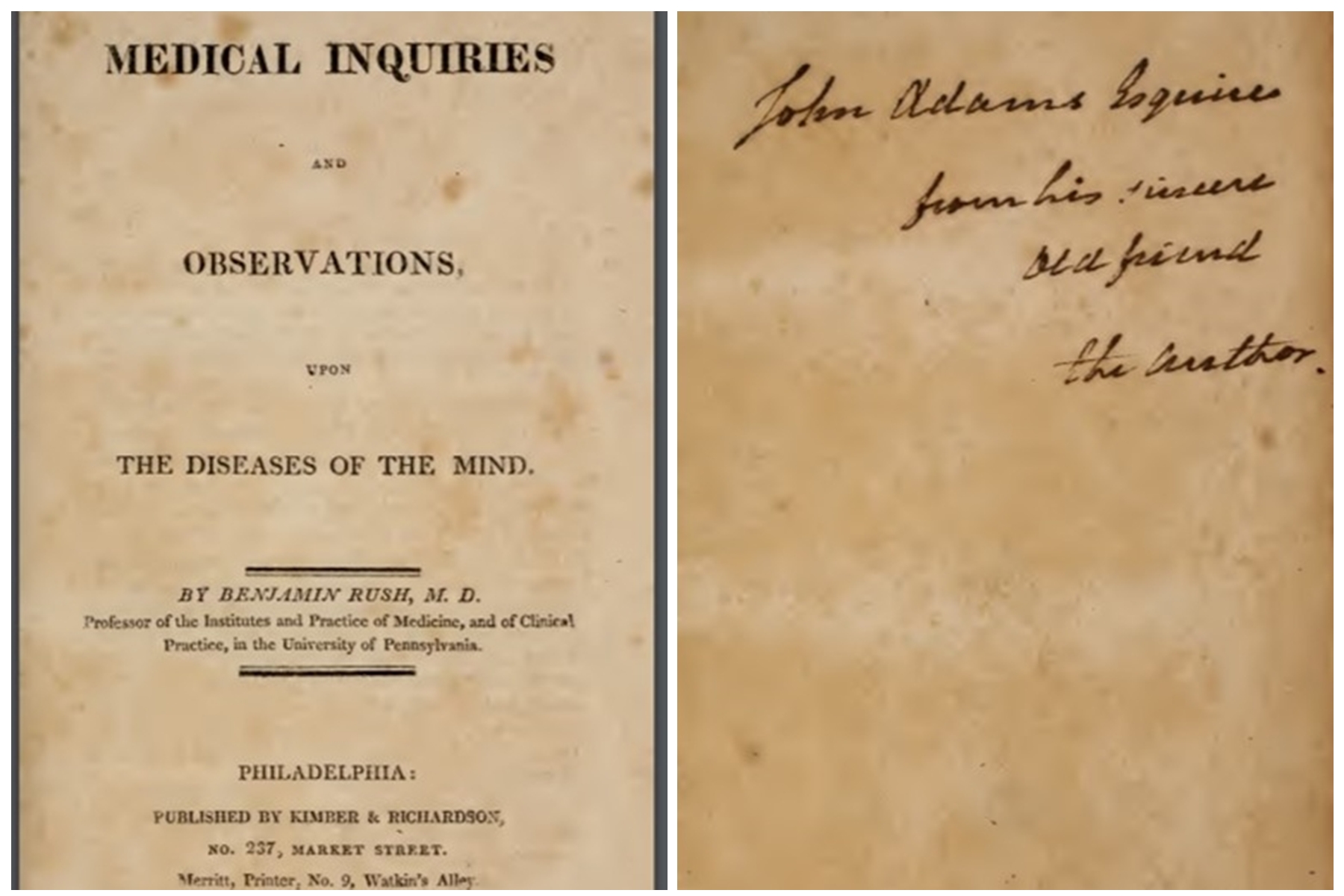

He held his life together, just barely, with the help of his wife and children, his colleagues and students, and the friendship of John and Abigail Adams. While Rush and President Adams developed political disagreements as the nation split into Federalists and Republicans, they had much in common personally. They were both married to strong, bright women they relied upon as reality checks. And among their broods of children, each had a son who was a rising star: Rush’s son Richard would become a cabinet member for three presidents, including Adams’s son John Quincy, whom he also served as a vice presidential running mate. Each also had an equally promising son overwhelmed by private struggles. Adams’s son Charles died from alcoholism at the age of thirty, just as Adams lost the presidential election of 1800 to Thomas Jefferson. Several years later, Rush’s eldest child, Lt. John Rush, a navy surgeon he had hoped would take over his practice, descended into mental illness, triggered in part by a tragic duel. He would spend the rest of his life in his father’s care, and his situation would inspire Rush’s last and most influential book, the first American volume on “diseases of the mind.”

Adams cut off all contact with Rush after his bitter defeat in the election of 1800. Rush remained in touch with Jefferson, who made him medical adviser to the Lewis & Clark expedition. But he didn’t hear from Adams for nearly five years, until the aging president decided to reach out, with one of the great first lines in American letters: “it seemeth unto me that you and I ought not to die without saying good-bye.”

His letter reignited an impassioned correspondence that stretched over their remaining years and allowed two old founding friends to retell their own stories and the story of their nation with unique perspective, humor, and candor. Rush eventually used the correspondence to try and heal the broken friendship between Adams and Jefferson, which he considered his duty as a friend and a patriot. He worked on each of them for years, in what would be his final act as a Founding Father. Not long before his death, they reconnected.

Adams wrote that Rush had contributed more to the American Revolution than Franklin—beginning with what the doctor and his fellow Philadelphia Sons of Liberty told him the day they met in 1774. Adams once told a cabinet member that without that surprising advice, “Mr. Washington would never have commanded our armies, nor Mr. Jefferson have been the Author of the declaration of Independence. . . . This conversation and the principles facts and motives suggested in it . . . [gave] a colour complection and character to the whole policy of the United States.”

Through it all, Benjamin Rush contended openly and engagingly with the same challenge he had put to the new nation: how to be a man of science, a man of liberty, and a man of faith — all while striving to be a good friend, husband, and father of nine children. Rush was a medical pioneer and a political pathfinder, donating his time, his money, even, at times, his sanity for the causes he worried were beyond the reach of laws. His life and writings provide a guided tour through the most public and private moments of the Revolution and the creation of America, seen through the eyes — first awestruck, then frustrated, and finally worldly wise—of a physician and reformer who was, in every sense, revolutionary.

And yet, after Rush died in 1813 at the age of 68, those who loved him most, and best understood his achievements, took steps that prevented his full story from being told.

Rush had been controversial in many ways. He was referred to as “the American Hippocrates,” sometimes as a compliment but other times as an insult to his outsized ego. He openly criticized powerful slave owners — even during the ten years after the war when he owned an enslaved person himself. He had questioned George Washington’s leadership when the war was at its bleakest, for which the general, once his friend, never forgave him.

The recriminations over the 1793 yellow fever epidemic never really ended — including a fight between Rush and his neighbor, Alexander Hamilton, who claimed to have been cured by another doctor with a milder treatment (leading Jefferson to claim Hamilton had never been sick in the first place). As each summer ended, fear and loathing of yellow fever and its treatments returned in major American port cities. While this made Rush even more famous, his popular books and public persona made him an even riper target. He even got caught up in—and won—one of the nation’s first major libel trials to defend his reputation and treatments.

All his life, his capacious mind was paired with a fast, glib tongue, and he was sometimes caught rushing ideas into print before he had thought them through. Yet, in the end, it wasn’t so much what he had said and done that made his most powerful friends worry. It was what they had told him. Adams and Jefferson especially had shared years of confidences about their feelings, their politics, their religion—even their bathroom habits—with Dr. Rush: the kind of information men mindful of their legacies might not want entering the historical record. Rush was the founder who knew too much.

Only weeks after Rush’s death, Jefferson urged his family to return the most revealing letters he had sent the doctor. He feared how “bigots in religion, in politics, or in medicine” might react if they were ever allowed to read them. And when a writer approached Adams about publishing a collection of the great doctor’s correspondence with him, the former president admitted, “I shudder at the thought. A complete collection of Dr. Rushes letters never will be published, or if they should, they would excite as much surprise and as much learned controversy and more factious Fury, than if a collection of Hypocrates had been dug out of the Ruins of Herculaneium.”

Newspapers at the time compared the death of Benjamin Rush to the loss of Washington and Franklin, and he was mourned across the country. But beginning with Adams and Jefferson, and helped along by his own family—especially his politically ascendant son, Richard, who had his own reasons for suppressing his father’s writing—his legacy dimmed. He became a footnoted founder, a second-tier signer.

As a result, many Americans know very little about Benjamin Rush.

I think about this a lot while sitting on the small bench near his grave at Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia’s historic district. The original six-foot-high redbrick wall still surrounds the cemetery, guarding it from the present and separating it from the large buildings now nearby: the National Constitution Center and the U.S. Mint. The bench is near the oak tree under which Rush and his family are buried. His grave is the most prominent in the family plot, a large but simple sarcophagus. He is flanked by his wife and his mother. And nearby, marked by a headstone eerily eroded so only the tops of the letters are slightly visible, are two John Rushes who haunted him: his father, who died too soon, and his son, who was felled by mental illness.

The doctor spends eternity here with Benjamin Franklin and three other signers of the Declaration; with Dr. Thomas Bond, who started America’s first hospital with Franklin and helped mentor Rush; with Dr. Philip Syng Physick, one of Rush’s protégés who later became known as the “Father of American Surgery”; with Matthew Clarkson, who was mayor of Philadelphia during the three months that made and unmade Rush, the 1793 yellow fever epidemic; with John Dunlap, one of Rush’s publishers and the first printer of the Declaration; and with others of Rush’s friends and patients.

The bench is a peaceful place, a perfect spot to ponder the questions about life in America that Benjamin Rush was one of the first to ask — of himself and of his towering contemporaries, whose intentions we debate to this day. What all this questioning about liberty, morality, and equality came down to, for Rush, was health, in the broadest definition of the word. Physical health, mental health, spiritual health, economic health, political health, public and private health. He saw the American experiment through the prism of diagnosis; he saw everything that was wrong as something that could be treated; and he saw every lost patient as an opportunity to save the next.

He also understood, as a physician and scientist, how many things he knew for certain would later be proved wrong; how many diseases, medical and social, could appear to be cured but later recur. In this was the “peculiar happiness” of cautious optimism, the comfort and discomfort of the truly long view.

History would one day rediscover and appreciate Rush, he was certain of it. As he once wrote: “The most acceptable men in practical society, have been those who have never shocked their contemporaries, by opposing popular or common opinions. Men of opposite characters, like objects placed too near the eye, are seldom seen distinctly by the age in which they live. They must content themselves with the prospect of being useful to the distant and more enlightened generations which are to follow them.”