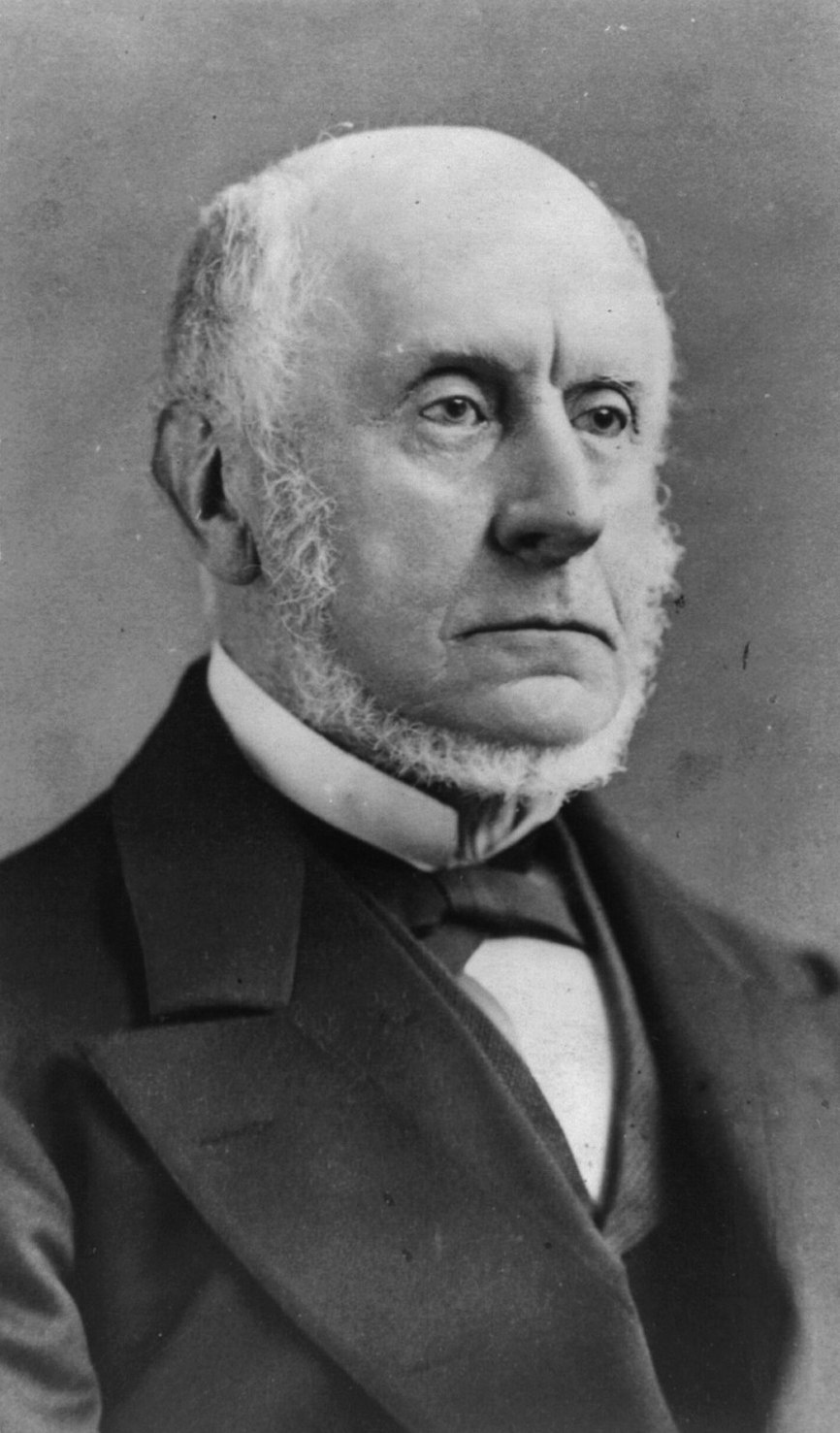

After his father's death in 1848, Charles Francis Adams, Sr. became the last great hope of America's first—and, at the time, only—political dynasty.

-

Fall 2020 George Washington Prize

Volume65Issue8

Excerpted from the George Washington Book Prize finalist Heirs of an Honored Name: The Decline of the Adams Family and the Rise of Modern America, by Douglas R. Egerton (Basic Books).

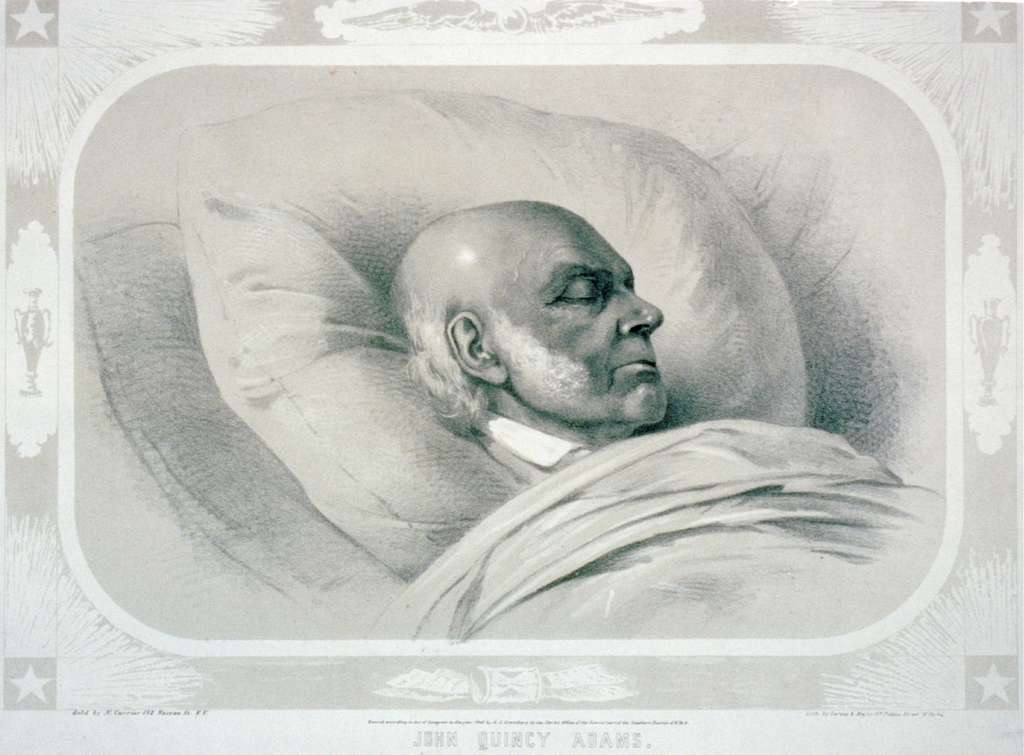

Henry Brewer Stanton was the first to notice. The United States House of Representatives had just wrapped up debate on a resolution to thank American officers and soldiers for their "splendid victories" in Mexico, and John Quincy Adams, who had long denounced the conflict as a "most unrighteous war," had cast one of the few nays, voicing his disgust in an "emphatic manner and an unusually loud tone." Stanton, a reporter for the antislavery Boston Emancipator and Republican and the husband of feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was sitting 20 feet from Adams when he observed the 80-year-old congressman suddenly make an "effort to rise," reaching out "with his right hand as if to take his pen from the inkstand."

Adams grew flushed, then paled and clutched the desk with a "convulsive effort" before sinking to the left side of his chair. Congressman David Fisher, an Ohio Whig, caught Adams as he fell, while Congressmen George Fries and Henry Nes, both of whom were physicians, rushed to his aid. "Mr. Adams is dying!" somebody shouted.

Both the House and Senate promptly adjourned, as did the Supreme Court, housed downstairs, but no one left the building. Many crowded in to see whether Adams yet lived. In a few "broken, disjointed and incoherent words," Adams mumbled something about his wife, and those in the chamber believed they heard him whisper, "My son, my son." Most of what he said next was hard to comprehend; some understood him to say, "This is the end of the earth. I am composed." Others thought him to murmur, "This is the last of the earth. I am content.”

The next morning, some four hundred miles to the north, Charles Francis Adams Sr., John Quincy's and Louisa's only surviving child, stopped by his Boston office at the Daily Whig and spied a telegraph sent by his friend, Congressman John Gorham Palfrey, dated the previous afternoon. "Here was a shock," Charles Francis scribbled into his diary. His father "was taken in another fit of paralysis and it was not thought he could survive the day."

Adams dashed home to inform his family and then caught the next train south. John Quincy had suffered a small stroke two years before but had quickly regained his health. "He has been the great landmark of my life," Charles Francis wrote. Although he was now forty-one and had been "accustoming myself to go alone," the son yet regarded his father as his "stay and companion."

Adams died that evening without uttering another sound, the speaker announcing his death to the assembled chamber on Thursday. Old John Adams had perished, fittingly, on the Fourth of July, but his son, one journalist marveled, "died in the Capitol itself, and almost upon the birthday of Washington." It was a "fit end for a career so glorious."

Charles Francis had reached Philadelphia on Wednesday evening and took a room at the Jones Hotel. He awoke on Thursday morning with "the dull, heavy sense of existing pain which comes with calamity." Seeing a man reading a newspaper with black borders, Adams purchased a copy at the depot but tucked it under his arm until the train was underway. "I threw open the paper I had bought, and the first thing I saw was the announcement that at a quarter past seven last night my father had ceased to breathe," he confided to his diary. "I have no longer a Father. The glory of the family is departed and I, a solitary and unworthy scion, remain overwhelmed with a sense of my responsibilities."

Charles Francis at last arrived in Washington on February 24. For four decades, Charles Francis had looked to his father "for support and aid and encouragement." Now he "must walk alone and others must lean on" him. Two brothers and a sister had died young, leaving Charles Francis "alone in the generation." But one deceased brother left behind two children, and Charles Francis had five of his own, with a sixth due in four months. That realization "brought me to a sense of my duty," Adams wrote that evening in a sentiment his father would have admired. ''A tear or two was all," and then Charles Francis returned to the Committee Room to talk politics.

The capital descended into mourning. A hastily assembled committee of Congressman Abraham Lincoln and Senator Jefferson Davis, together with their future vice presidents, Hannibal Hamlin and Alexander Stephens, gathered to make arrangements for the first state funeral since President William Henry Harrison's death in 1841. President James K. Polk put aside his long-standing disdain for the antislavery congressman and ordered the executive mansion and all the departments draped with black cloth. Most private residences in Washington followed suit. Shops closed their doors and shuttered their windows. Within the House of Representatives, doorkeeper Robert Horner shrouded the statues in the chamber, with the exception of the white marble figure representing History.

The funeral was held the following Saturday, February 26. Pennsylvania Avenue was "dressed in mourning throughout," newspapers reported, and "flags everywhere floated at half mast." A long black pennant waved from atop the Capitol dome. The service itself was held in the House chamber. Louisa could not bring herself to attend, so Charles Francis and his sister-in-law, Mary Hellen Adams-the widow of his brother John-represented the family and sat facing the coffin, now covered with black velvet fringed with silver. Seated behind the family was Washington's elite, from Polk and his vice president, George Dallas, to his cabinet and members of the Supreme Court.

After a eulogy by House Chaplain Ralph Gurley, pallbearers loaded the casket aboard a carriage decorated with a gilt eagle and pulled by six white horses. Capitol bells rang out as the procession shuffled toward the Congressional Cemetery on the banks of the Anacostia River, from where Adams's remains would be shipped north to the family plot in Quincy, Massachusetts. Editors filled their columns with tributes to John Quincy, who had received his first public position in 1796, when President George Washington had nominated the twenty-six-year-old youth to serve as minister to the Netherlands.

As Charles Francis prepared to return north with his father's remains, a lengthy note of sympathy arrived from Henry Clay, who had known John Quincy since their days as peace negotiators in Ghent during the War of 1812. "No surviving friend of your father sympathizes and condoles with you all, with more sincerity and cordiality than I do," Clay insisted. Predictable hosannas to the former president's career as "patriotic, bright, and glorious" followed.

But then Clay signed off with a comment that surely gave Charles Francis - the son and grandson of presidents - a moment of pause. Since the 1770s, the name Adams had "shone out, with the brightest beams, at home and abroad," Clay observed. "May its lustre, in their descendants, continue undiminished." Whether Clay meant it as such, that was a daunting challenge.

It was also a challenge the son would have to face alone. Each time an American founder died, the nation debated what that loss meant for the present and what that statesman's legacy held for future generations. One newspaper editor pondered the math. The Constitution had been in effect since 1789, and in that "period of 59 years, we have had eleven Presidents. Eight of that number had "sunk into the tomb; and only one of them (Mr. Adams) leaves a son behind." Of the three living presidents, both Martin Van Buren and John Tyler (who sired fifteen children by two wives) had living sons.

But Charles Francis was unique among the group in that he could claim two of the eleven presidents as his lineage. Later generations would come to regard the Adams family as America's first political dynasty, but for those trying to take the measure of a man who had literally died within the Capitol's walls, Charles Francis represented the hopes of what was then American's only political dynasty. A decade later, on the eve of his own election to Congress, Charles Francis reflected on the almost crippling burden that this inheritance imposed on his family. "The heir of an honored name, and of men who have distinguished themselves in the most difficult of all careers, has a trying position anywhere, but most of all in America," he wrote. "Every act of his is contrasted, not with those of common men, but with those of persons whom all have united to produce very extraordinary specimens of the race."

Should he or his sons fail to obtain the status achieved by earlier generations, his countrymen might regard that as a tragic "moral about the degeneracy of families." But "if by some miracle he should happen to reach a still higher point" than his illustrious ancestors, residents of "all free countries," Charles Francis worried, could rightly grow concerned about one family's claim to govern on the grounds of "inherited abilities, or greatness." As a boy and then a young man, Adams had watched as his grandfather and father were not merely criticized but also bested by men they regarded as of lesser abilities, and throughout the remainder of his life, he would ever be ambivalent about taking up Clay's challenge.