When the Pentagon wanted a photographer to record the largest airborne assault in the Vietnam War, the most qualified candidate was a young French woman.

-

Fall 2023

Volume68Issue7

Editor’s Note: Elizabeth Becker is a respected war correspondent and award-winning author, having worked for The New York Times, National Public Radio and the Washington Post. Among her books is You Don't Belong Here: How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War, from which the following was adapted.

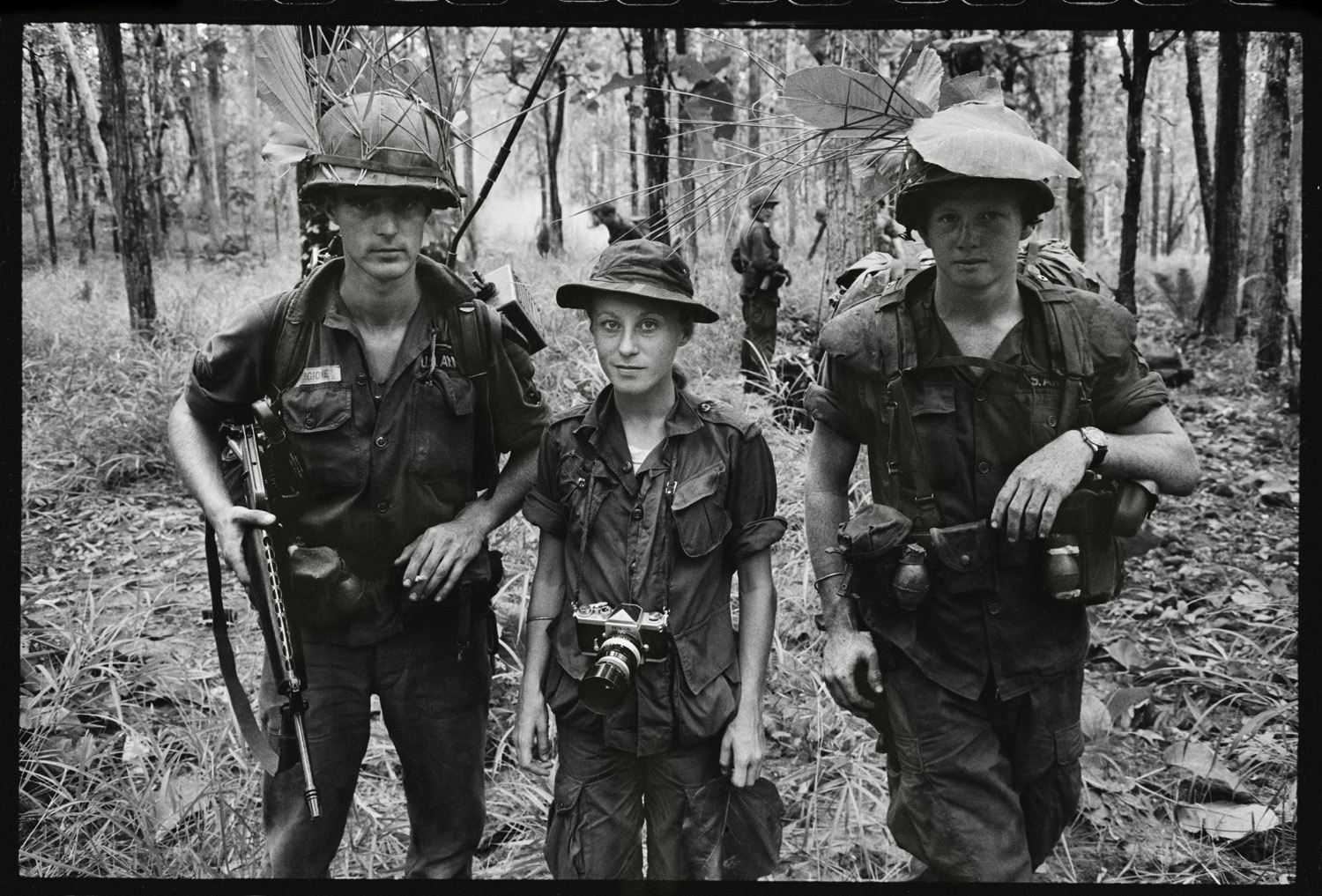

When they gave the twenty-minute warning, Catherine Leroy was waiting in her assigned seat on the left side of the C-130 cargo plane, the air thick with the heat of Vietnam’s dry season. She was quiet, trying to blend in. Leroy was the only journalist on the plane, the only photographer. She had two cameras draped around her neck, and she was the only civilian and the only woman. Her US Army-issued parachute nearly swallowed her. At five feet tall and weighing just 87 pounds, she was tiny compared to the dozens of US Army parachutists sitting alongside her.

It was February 1967, and Leroy had been selected as the best person to capture on film the United States’ first airborne assault in the Vietnam War. The Pentagon hoped to repeat in the tropical jungles of Southeast Asia the success of World War II airborne operations that helped shift the course of that war. After more than a year of mixed results, the US military wanted a big win.

The day before, Leroy had been called to the Office of Public Information at the Military Assistance Command Vietnam or MACV, the headquarters of the US Armed Forces in Saigon. Not sure if she was in trouble, Leroy was relieved when she was asked just one question: Did she still want to jump?

Shortly after that, she was assigned to the 173rd Airborne Brigade and sworn to secrecy until the operation began. She barely slept, rose with the troops before dawn, and climbed onto the truck convoy to Bien Hoa Airport, 16 miles northwest of Saigon. She boarded the seventh plane to shouts of “Airborne all the way!”

The target was a battleground near the border with Cambodia. Leroy listened as the plane rose, excitement overwhelming her. Her stomach cramped.

The cavernous plane flew for more than an hour before the paratroopers heard the telltale drone of the engine slowing, signaling that the pilot was near the target zone. She photographed the game faces of the soldiers the moment the jumpmaster began the countdown. “Get ready! Stand up! Hook up! Check static lines!”

Soldier after soldier hooked onto the line of steel cable suspended above them, stamping their feet and shouting. The green light above the door lit up. “Go!”

Leroy fell in with the others. The jumpmaster grabbed the static lines, guiding each soldier out with a “go, go, go, go.” Like a controlled explosion, the men thundered down the long dark aisle toward the back of the airplane, Leroy keeping pace with them.

She jumped out the door, butterflies in her stomach, her dark blond pigtails lifting as she fell. Then: “Everything became light.” Her parachute opened into the cool air, with no trace of wind. From above, the menacing jungle was an undistinguished blur of deepening shades of green. Almost beautiful.

She grabbed the Leica, then the Nikon cameras around her neck, and photographed the hundreds of parachutes as they opened. She shot their images from above and below and sideways. Even in their helmets and heavy boots, the soldiers reminded her of flowers opening their petals. In no time, the lush earth raced up to meet her. “I landed in a drained rice paddy, lovely and springy and soft, rolling over in my easiest landing.”

Operation Junction City looked majestic in Leroy’s photographs that first day. Soldiers hit the ground running. This tropical assault was a search-and-destroy mission in Tay Ninh Province in southwest Vietnam. The soldiers dispersed over rice paddies and villages looking, sometimes blindly, for the elusive headquarters of Vietnamese communists.

Stunned villagers huddled near their empty huts, ordered out by towering American soldiers in a search-and-destroy mission. Their faces resigned, the villagers were rounded up and banished from their homes, leaving behind ancestor altars and pig stys. They cradled bedrolls and cooking pots; they were displaced to refugee camps.

With so much riding on the operation, other reporters had demanded to be on the ground with the paratroopers. Many were upset, some even disdainful, when they found out that Leroy would be the only accredited journalist to jump. For over a year, she had been the only woman combat photographer in Vietnam and had given up trying to change men's attitudes.

Even the great photographer Don McCullin, who admired her work, was taken aback seeing her on the battlefield. “She did not want to be a woman amongst men, but a man amongst men. Why would a woman want to be amongst the blood and carnage?… I did have that kind of issue with Cathy.”

After the initial landing, the rest of the press arrived by land and filed their stories. The next morning, Brig. Gen. John R. Deane showed up in the press tent with a surprise for Leroy. He pinned the master jump-wings badge, its gold star signifying a combat jump, onto her shirt.

“Wear this,” he said. “That was your eighty-fifth jump.”

She wore the badge permanently on her crumpled fatigues, an eloquent rejoinder to anyone who had questioned whether she was qualified to cover the war.

Catherine Leroy had lobbied to accompany the paratroopers ever since she arrived in Vietnam from Paris in 1966. Few other press photographers were remotely able to jump with the airborne troops. Leroy had earned first- and second-degree parachute licenses in France while still in secondary school, initially egged on by a boyfriend who had dared her to try it. She jumped 84 times over the vineyards and meadows of Burgundy.

At that same time, Leroy was becoming serious about photography. She found a job at a temporary hiring agency, abandoned any idea of finishing school, and in her free time roamed Paris, practicing with her camera. Working overtime, she saved enough francs to cover the costs of a Leica camera and a one-way ticket to Vietnam. After her twenty-first birthday, when a French person could legally leave home without parental consent, she told Jean and Denise Leroy that she was going to Vietnam on her own for three months.

In France, this was especially gutsy for a female, since the French were behind the times in gender equality. French women had only gained the right to vote in 1944. But Leroy told her parents a white lie: she would go only long enough to photograph a nice feature story on women in Vietnam. In fact, she was fully focused on being a war photographer, getting as close to the battle as she could.

“Photojournalists are my heroes. I want to be a photojournalist. The biggest story in the world right now is the Vietnam War,” she wrote to a friend.

Knowing next to nothing about Vietnam, she arrived in Saigon in February 1966.

During her first days there, she called on Vietnamese and French contacts — friends of friends whose names she had collected in Paris. She introduced herself to officials at the American military headquarters where she received press credentials based on a letter from Paris Match magazine promising to consider publishing her photographs. She called the press pass her “open-sesame card.”

After bouncing around Saigon, she rented a room for a few nights at the elegant Continental Palace Hotel, a French oasis in the heart of the city across from the ornate Opera House. She convinced Mr. Le, the hotel manager, to allow her to use the hotel as a mail drop once she found much cheaper lodgings.

Saigon still resembled a tropical provincial French city, as the colonialists had intended. Leroy send her mother reassuring letters that she had landed on her feet. Saigon, she said, “is a very pleasant town that you would like. People are insouciant and smiling. Many Americans in civilian dress. All this doesn’t give the impression of being in a country at war.”

Christian Simonpietri, a photographer who met Leroy in the early days, saw something else: a slight young woman distinctly out of place. “She was walking around the city center with only a few dollars in her pocket and a Leica camera strapped around her tiny neck. A tiny French person with a blond ponytail,” he said. “She looked lost, so helpless. That is why we became friends.”

Later that month, her confidence and wardrobe boosted, this petite woman with a long elfin face and piercing blue eyes walked into the Associated Press office in the Eden Building opposite the Continental Hotel. Unannounced, she introduced herself to Horst Faas, the editor of photography. Catherine Leroy had decided to jump-start her professional life.

Faas was a minor deity to photographers, especially freelancers. A talented photographer himself — he had won the Pulitzer the year before for his Vietnam War photographs — he was also an unusually gifted editor. His organizational skills, his grasp of history and photography’s influence on events, and his deft handling of photographers helped put the Associated Press at the top. Above all, he had an eye for the most expressive photographs. Under his watch, the AP was the source of the best war photographs in Vietnam.

He was also a kingmaker. He took one look at Leroy and, new wardrobe notwithstanding, was not impressed. “She was a timid, skinny, and very fragile young girl who certainly didn’t look like a press photographer,” he thought.

He told her as much. “I’m not used to a young woman photographer,” he said. “I don’t know how you’ll be perceived out there. Maybe you should concentrate on the Vietnamese and life in Saigon — pictures that war photographers normally wouldn’t like to take.”

Leroy would have none of it. “No, no,” she answered back. “I am a paratrooper.”

Faas laughed: “You — a paratrooper — I can’t believe it.”

Luckily for her, beneath his daunting facade, Faas had a distinctly open-minded attitude within his profession. A German born in Berlin in 1933 who had grown up with war’s sorrows, he worked easily with photographers from around the world. They all respected him, not only for his evident talent, but because he was fair, decisive, and exceedingly hardworking. And he gave them a chance to prove themselves.

But women? Faas’s policy as photo editor, then a rarity, was to buy good photographs, no matter who took them. Even, now, from a woman. During that first meeting, they spoke in French. Leroy barely remembered English from her party days in London, although she had already started to Americanize her name, introducing herself as Cathy.

Faas gave her several rolls of film, an essential gift, since freelancers couldn’t afford to buy their own. Then he delivered his routine conditions leavened with his dry humor. Once you’ve taken your photographs, bring back the film and AP will develop it in the bureau’s darkroom. Photographers receive $15 for every photo purchased by AP, and AP retains the copyright on all these photos. No discussion.

With Faas’s implicit encouragement, Leroy won a degree of legitimacy denied to other young women who had to spend months proving they were good enough to even be considered for freelance work.

Her first time under fire, Leroy instinctively ran for cover and joined a group of Vietnamese who had been chased from their homes. They gave her a bowl of soup and chopsticks. “This is delicious,” she said in French, and then ran further to avoid the fighting as it closed in.

“I ended up near a shop making headstones.” She took more pictures of Vietnamese civilians—children as well as adults “huddled under sniper fire behind gravestones in the stone mason’s yard.” It was a chaotic insurrection with no sign of communist propagandists or provocation.

Faas bought two of her photographs, haunting images of Vietnamese civilians hiding behind tombstones as they were fired on by their own government. When he sent Leroy’s first photos over the wire to New York for sale around the world, her excitement matched only her determination to continue photographing for him.

From that moment, the AP Saigon bureau became a second home to Leroy. Returning from the field, she walked up four flights of stairs because the elevator rarely worked. The familiar walls of the office were crowded with framed articles and photographs of reporters who had died covering the war; the floors were strewn with flak jackets, boots, and the gadgets photographers required, and the hallway permanently smelled of nuoc mam, the ubiquitous Vietnamese fish sauce, and urine. She slumped into an armchair, wrote her captions, and handed the negatives to Faas.

Just as familiar was her routine after leaving the AP office. She would return to her small rented room, shower off the dirt from working days in the field, and then crawl into bed, sleeping eighteen hours at a stretch, sometimes a whole day: “I slept as if I had no desire to ever wake up.”

She was driven to prove her worth. She won awards never before given to women, and changed the look of war photography. But her success bred resentment among the male reporters and photographers. They repeatedly pushed the military authorities to revoke her certification.

The reasons given were couched in personal terms. It was said Leroy was pushy, ambitious, shoving to get on a helicopter to the battlefield or back to Saigon with her film. She had no manners. In the field, she could be a hothead. When she didn’t get her way, she would flare up, sometimes using profanity. She swore.

It made no difference that male journalists also had tempers, also swore, also threw their weight around to get what they wanted, and also were ambitious. Leroy was expected to be lady-like. She was an interloper who had become an affront to the profession. It came down to her gender: she didn’t belong because she wasn’t a guy.

Alain Taieb, a French photographer, had briefly befriended her, seeing her as a lost soul, until he realized she was serious and was actually becoming a real war photographer. For him, this was impossible. She was strange and small; she tied her Leica camera around her neck with a shoelace. He told her that being a photographer in Vietnam was a boy’s job, not a girl’s job. He and other French journalists insisted that she wasn’t qualified: “She had no money, no job, no manners, no nothing.”

This was also absurd. Taieb himself had arrived in Vietnam with no experience, no money, and no job.

Catherine Leroy was astounded that her colleagues would betray her. She wrote her mother that Taieb and another photographer were acting like “real bastards.” Decades later, Taieb apologized to her and said he was “not very proud of the way we treated her.”

The worst was yet to come. Some reporters decided to lobby the authorities for Leroy’s official exclusion. Francois Pelou, bureau chief of Agence France-Presse — the equivalent of the dean of the French press corps — went behind Leroy’s back and denounced her in a complaint to the US military press office. He said her behavior “cast reflections upon the whole press corps to the extent that others are having difficulty winning the cooperation of troops after she leaves an area.”

Once Pelou broke the ice, others followed. Leroy became a target.

Peter Arnett, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his Vietnam coverage for the Associated Press, wrote in his memoir that he saw Leroy swear at an aircraft commander at Dang Ha when she was told there was no room for her in his helicopter. A male reporter engaging in such behavior would have generated no protest whatsoever.

One military spokesman wrote an unsigned note: “Isn’t the evidence sufficient to lift accreditation?”

That became the goal: create a thick secret file, nicknamed “the black book,” that would justify taking away Catherine Leroy’s press credentials so she couldn’t work.

Her colleagues did not stand up for her. As Peter Arnett wrote: “The Vietnam press corps was a male bastion that women entered only at the risk of being humiliated and patronized; the prevailing view was that the war was being fought by men against men, and women had no place there.”

Arnett explained that the men actively worked against the women: “We reporters tended to disparage the abilities of women, and gossip about them and their relationships, and were uninterested in helping them out with the authorities.”

But when the military moved to take away her press credentials, they had a problem. Leroy had obeyed the basic rules. She had not violated security considerations endangering troops, written bad checks, assaulted military spokesmen, or fabricated her journalistic credentials. They had to make up an offense, and, in a wicked twist, the military said she was being suspended because her obnoxious behavior hurt her fellow journalists. “Her actions were such as to alienate working relationships with military personnel to such an extent as to make it difficult for newsmen to function effectively.”

On October 24, 1966, Colonel Rodger R. Bankson, chief of information at MACV, the US Armed Forces headquarters in Saigon, officially suspended her press credentials.

“Miss Le Roy,” he wrote, “Since my last letter to you, we have received additional reports concerning your conduct while associated with military units in the capacity of a correspondent. These incidents are of such a serious nature that a decision has been made not to renew your MACV accreditation. You are requested to turn in your present accreditation card to the Special Projects Division on 30 October. Sincerely yours.”

Without her press credentials, her photojournalism career in Vietnam would be over. The military even sent letters to her outlets in Paris to tell them that her behavior had led them to suspend her credentials. No stone was unturned to ruin her career just weeks after it had finally blossomed.

Leroy panicked. She “felt like jumping in the Mekong.” She had been shoved out the door by the military with the assistance of some of her colleagues. She was furious. If the ban was not lifted, she would be forced to return to Paris and work in a dreary “insurance office.” She was so humiliated that, for weeks, she couldn’t write her parents or anyone else. For the first time in her young life, she couldn’t resolve her difficulties by simply running away.

Instead, she had to learn to stand her ground and fight back, quickly. She was told that the most serious charge of bad behavior was made by officials from the hospital ship Repose. She got in touch with her host on the ship, and three days after MACV had revoked her press credentials, Lt. Paul E. Pedisich of the Navy’s Seventh Fleet’s information office sent a short, unequivocal message to MACV that rebutted the charge against Leroy. It read in full:

“Miss Leroy conducted herself in a complete, charming, and lady-like manner while on board the REPOSE. Left with warm invitation to return whenever she could.”

Her strongest supporter was the man whose opinion counted the most: Horst Faas at AP. He wrote a letter attesting to her professional standing and dispelling any hint that she was an unwelcome colleague or a fraud. Writing on Associated Press letterhead, Faas used the clear, commercial language of success: Leroy’s photographs were good enough to be published in the highly competitive world market. She had sold spot photographs and photographic series she had taken of combat operations in all of the US military corps areas in Vietnam, earning at least $1000 (the equivalent of over $9000 today) after only seven months in Vietnam.

In other words, Leroy was not the uncouth amateur undermining her colleagues, as portrayed in that black book of complaints, nor a vagabond who should be dismissed as a frivolous woman seeking adventure, as her male colleagues called women freelancers.

Bryce Miller, bureau manager of United Press International, followed Horst Faas with a more perfunctory note “to certify” that UPI had purchased photographs from Leroy and “will consider any pictures in the future she may have to submit.”

Leroy’s reputation, though, would never recover. From then on, she was branded a spitfire and a troublemaker, an uncouth, foul-mouthed woman. But MACV eventually relented, and she proved herself on the challenging campaign with the 173rd Airborne paratroopers.

Despite her success, Leroy’s press credentials were soon jeopardized again. In 1967, all female journalists in Vietnam were put on notice that the US military was planning to reimpose a lighter version of the World War II regulations prohibiting them from reporting on the front line. The military still didn’t believe women belonged in a war zone.

It was explained to one female journalist that Gen. Westmoreland feared women “might inconvenience or endanger soldiers who would rush to protect us.” He also worried that women correspondents would collapse emotionally when “faced with the horrors of war.” Westmoreland proposed a compromise edict that would prohibit women journalists from spending nights with troops in the field. It wasn’t a complete imposition of the World War II ban, but it might as well have been.

The handful of women journalists in Saigon recognized that their “livelihoods are being destroyed.” Five American women, largely strangers to one another, set up an ad hoc committee to fight the ban. Catherine Leroy was asked to be one of the women who signed a letter asking that the edict be nullified.

The American women then petitioned the Pentagon to drop the proposed Westmoreland ban. Their unofficial leader was Anne Morrissy, a young but seasoned field producer who had convinced ABC News to send her on assignment to Vietnam.

Defense Secretary Robert McNamara said he would listen to their argument and sent an assistant to meet with them. After an afternoon and evening of martinis, it became clear to Morrissy that the ban was unsustainable and that the Pentagon representative knew it. He told her that Westmoreland’s proposed ban “would be lifted and we could go back out in the field.”

No one publicized the near expulsion. The women never wrote stories about it or told their male colleagues. Women were still on a leash, even though the ban was effectively shelved.

Nonetheless, the impact of their pushback was profound. They had removed the American military’s biggest impediment to women war correspondents. The United States military never again attempted to prohibit women reporters en masse from the battlefield.

This was the only time the women journalists banded together, let alone as sisters or even friends. Afterward, they went their separate ways, cut off by their work, by the stress of proving their professionalism, and by the pace of war.

For Cathy Leroy, her career saved from a second near-collapse, the next step was simple: She informed her parents that, despite her promises to come home, she was staying on.