After her death, Dickey Chapelle’s editor at National Geographic paid tribute to the gutsy war correspondent he knew.

-

Fall 2023

Volume68Issue7

Editor's Note: Bill Garrett was Dickey Chapelle's primary contact at National Geographic and often worked with her on assignments in the field. He wrote these observations about his friend and colleague shortly after her death. Garrett later became the Editor of National Geographic.

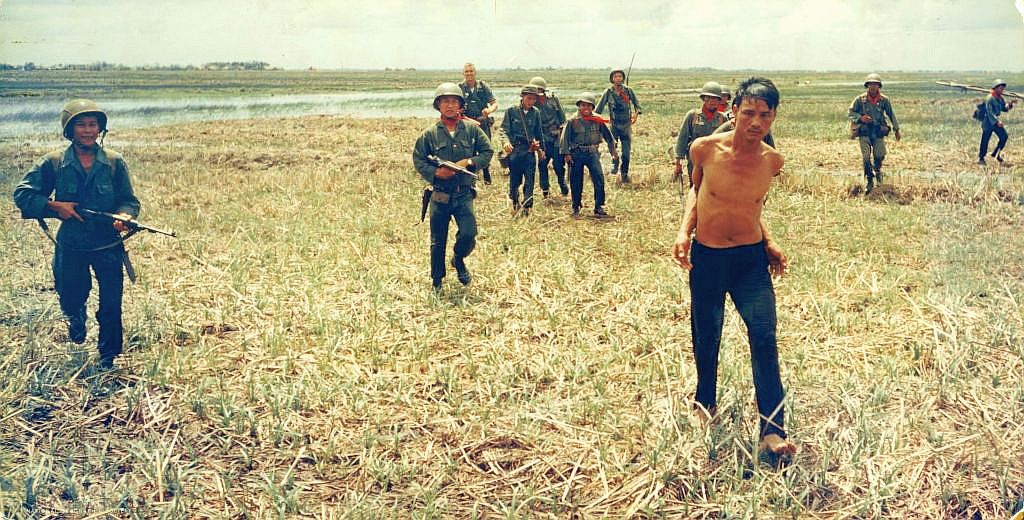

A rainbow decorated the western sky that early morning of November 4 — the second day of Operation Black Ferret. Action began at 0745 when American Marines moved toward a cane field surrounding a village held by the Viet Cong near Chu Lai, South Viet Nam.

A foot brushed a concealed nylon fishing line, a booby trap roared, and shrapnel shredded the damp foliage, felling six Marines and a lady from Milwaukee, Georgette Louise (“Dickey”) Chapelle. She died moments later, half a world from home.

What, you might ask, was she doing there? Dickey, a veteran war correspondent, had asked that same question in her autobiography, What’s a Woman Doing Here? Her mother had taught her that “violence in any form is unthinkable.” But she came to believe we could have peace only by being strong.

She became a correspondent in World War II to be near her husband, Navy photographer Anthony Chapelle. Perhaps it was the shock of photographing the death and horror of Iwo Jima and Okinawa that led her to dedicate her life to “telling the folks back home” how cruel war can be. Almost a quarter of a century later, her byline now famous, this remarkable woman is mourned in a dozen languages.

Because I knew and loved Dickey from working beside her in Cuba, Viet Nam, northeast India, and Ladakh near Kashmir, word of her death shocked and sorrowed me — but it did not surprise. Dickey and danger were never far apart.

The evening before her death, she dug her own foxhole and huddled under a poncho as a light rain fell through the glare of aerial flares. Though I wasn’t there, I’m sure she opened her breakfast of cold C-rations with the Swiss Army knife she always carried.

Staff Sergeant Albert P. Miville told me later what had happened next:

“She asked if she could go with us. I said, `Sure, Dickey; fall in behind me.’ Five seconds later, she was hit. I was only a step away. Some brush saved me. I yelled for a corpsman. He looked at her and told me, ‘Sergeant, there is nothing I can do.’“

The sounds of the violence she had been raised to abhor became the siren song that lured Dickey to every scene of political mayhem since World War II: Korea, Cuba, Quemoy, India, Algeria, Lebanon, Laos, Viet Nam, and the Dominican Republic. While helping smuggle penicillin to Hungarian freedom fighters, Dickey was captured and spent six weeks in solitary confinement, being subjected to terrifying interrogations, before the United States consul was able to free her. “Thank God I’m an American,” she said.

Personal integrity forced Dickey to write only stories she had “eyeballed” — to use her phrase. Official government handouts, complained Dickey, “have all the authenticity of patent-medicine ads.”

Never did Dickey tolerate favors in the field because of her sex. She hid her figure in loose khakis and bandoliers of cameras and film cans. Her long blonde hair, rolled into a bun, nestled in a floppy Australian bush hat. Makeup was not part of her field kit.

To keep in condition and not be a burden to the men she photographed and wrote about, Dickey ran two miles a day when in New York between assignments.

In 1962, after five weeks with the Indian Army on the Chinese front, Dickey and I were flown directly to Calcutta, still in field gear. She excused herself at the airport, but returned almost immediately, laughing as she told me, in her gravelly drill-sergeant voice, how successful her disguise had been: “I just got thrown out of the ladies’ room.”

In the field, her only jewelry was the military insignia presented to her by fighting units. She fell wearing the globe and anchor of the Marine Corps Commandant, Gen. Wallace M. Greene, Jr., who took the insignia from his own uniform and gave it to Dickey before her departure for Viet Nam the previous fall.

Of her many honors, I suppose Dickey most treasured the Overseas Press Club’s award for “reporting requiring exceptional courage and enterprise.” When she wasn’t with her adopted military families, she worked for the club, serving on its Board of Governors.

Some who knew Dickey were ill at ease in the presence of her nervously loud voice and exuberant manner. But these characteristics stemmed from an enviable enthusiasm for life, and a dynamic mind and heart. Dickey found an identity and purpose in life we all envied. It freed her of inhibitions and fears.

She knew the odds against a moth that flies too close to the flame, but, for years, she beat those odds. She lived the hundreds of lives of the men she wrote about and photographed. Life was precious to her; her own was taken too soon. But she had used it well.

Excerpted from the February 1966, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC, "What Was a Woman Doing Here?" by Wilbur Garrett.