We've gotten one farce after another from the secretive judges at the Swedish Academy who confer the world's most prestigious prize for literature.

-

Spring 2019

Volume64Issue2

Last year’s scandal surrounding the Nobel Prize for Literature was only the latest in a history almost too farcical for Moliere. The Swedish Academy, the body that awards the literature prize, was embarrassed by credible allegations of financial misconduct, leaks of the names of winners, and sexual assault by the husband of one of the academy members.

So many judges resigned in disgust that the Academy was forced to cancel the 2018 prize altogether. It was such a royal mess that the executive director of the Nobel foundation – the body that oversees all of the prizes – said that the Academy “should get outside help” to sort out all their problems.

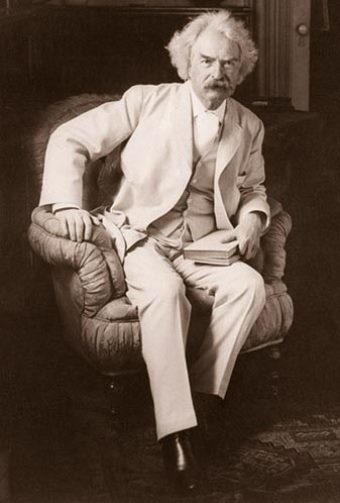

It turns out that last year’s scandal was far from being an aberration. From the beginning, the Nobel Prize for Literature has been a bit of a comedy of errors and omissions. The most frequently heard critique of the prize, particularly in America, is that it's perennially bestowed on obscure authors whom no one reads except their mother. Who, for instance, has ever heard of, much less read, the immortal words of Par Fabian Lagerkvist (1951), Ivo Andrik (1961), Odyssus Elytis (1979) or Wistawa Szymborska (1996)? Not to mention Bjornstjern Bjornson, Jose Echeragay, Henrik Sienkiewicz, Rudolph Christoph Euken, or Paul Heyse, all of whom won out over Mark Twain.

One explanation for the runic obscurity of many of the winners is that they were Scandinavians, mostly Swedes, whose works were not widely translated and whose fame never spread beyond their national borders. In this category we find Selma Lagerlof, the first woman to win the literature prize, in 1909; Henrik Pontoppidan, who wrote of peasant life in Denmark (1917); and the prolific Holldor Laxness (1955,) who wrote novels, plays, short stories, newspaper articles, and travelogues – all in Icelandic. Their words may be sublime, but we will never know.

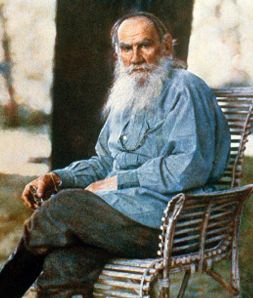

An even more serious criticism of the judges is their failure to acknowledge some of the greatest names in 20th century literature. We could start with Leo Tolstoy. The Academy began in 1901. It had years to award Tolstoy the prize before he died in 1910. But it didn’t. It was said that the conservative judges were troubled by his religious beliefs and increasingly radical political views as he grew older. But the real reason may have been the historic tensions between Sweden and Russia – a later Academician later claimed that one early judge so hated Russians that he prevented Tolstoy, Chekhov and Gorky from winning the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Then again Marcel Proust, Joseph Conrad, and Henry James – non-Russians all – never won either. All qualified before they died. In 1906, the Nobel Prize in Literature went to the Italian Giosuè Carducci, who was unanimously elected over the other nominees for that year – Mark Twain, Rainer Maria Rilke, George Meredith, and Henry James.

Later in the mid-20th century, those who were spurned included Franz Kafka, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, D.H. Lawrence, Vladimir Nabokov, W. H. Auden, George Orwell, Robert Frost, John Updike, Graham Greene, Arthur Miller, James Baldwin. The list of overlooked literary greats goes on and on, sealing the case that the Swedish Academy’s sins of omission virtually disqualify its choices as decisions to be taken seriously.

We can blame some of this on Alfred Nobel himself. Part of the problem in the early years was the selection committee’s faithful adherence to Nobel’s eligibility requirements, as laid out in his will. He decreed that the winners should exhibit “lofty and sound idealism.” A winner should have produced “the most outstanding body of work in an ideal direction.”

That apparently ruled out Twain and Henry James, who were passed over not once but numerous times before Twain died in 1910 and James in 1916. The same goes for Marcel Proust, who wrote more than 30 novels, some of them quite well remembered.

Another outstandingly egregious casualty of the philistine “ideal” standard was Henrik Ibsen, the author of Peer Gynt, A Doll’s House, Ghosts, An Enemy of the People, The Wild Duck, and Hedda Gabler. Some regard him as the most important playwright after Shakespeare, with an influence over countless later dramatists. Ibsen was passed over six times before his death in 1906, again amid arguments over whether his writings headed in a sufficiently “ideal direction.” Ibsen’s best-known heroine, Nora, on the contrary, was headed in the other direction, out the door of her stifling doll’s house.

James Joyce was never even a contender. Though some critics have called Ulysses the greatest novel ever written in any language, when Nobel Prize judge Sven Hedin was asked why Joyce wasn’t even nominated, he said: “Who?” And then of course there is that troublesome scene where Leopold Bloom masturbates on a park bench while watching a group of school girls. The book, published in 1918, was banned in the US until 1930, and one wonders how its hero would be received even today.

Virginia Woolf was also far too experimental and too intellectual for the upright gentlemen of the Swedish Academy. In 1938, at the height of Woolf’s career, 13 years after the publication of her stream of consciousness masterpiece Mrs. Dalloway, the prize went to Pearl Buck, a choice that critics still complain about.

Another female writer, Edith Wharton, whose books are now well-read classics, was never in the running. Like her good friend Henry James, she barreled on to fame and fortune without the assistance of the secretive Nordic judges.

And yet, despite the obvious cluelessness of these judges, many of those passed over have nevertheless been exceedingly uncool about being rejected. You’d think they’d shrug and say, who cares, it’s all so absurd! What do those snowbound provincials know about literature anyway? I know what I’m worth! Or why not heed what Flaubert said: “Honors dishonor the writer.” But no. Robert Frost’s biographers say that he was obsessed with winning the Nobel Prize, even though he won the Pulitzer four times and was a household name to millions of Americans.

I had occasion to personally witness the bitterness of another “loser,” Jorge Luis Borges, who was a perennial also-ran for 20-something years. I was the chief correspondent in South America for Newsweek in 1973, and in that year we wanted to interview the great man, who was once again considered a front runner for the prize. He was living in a fairly modest apartment in Buenos Aires and by that time was completely blind.

I found a dyspeptic, embittered old man – he was 74 at the time – railing about the Argentines (he himself was Argentine). “They call themselves gauchos,” he grouched, “but the Uruguayans are the real gauchos.” He thought he knew what he was talking about, as his mother was from an old Uruguayan land-owning family.

And he should have won. His brilliant surrealist writings inspired the magical realism of later South American masters like Gabriel Garcia Marquez, who did win a Nobel in 1982. But the story was that Borges’ reactionary politics got in the way. He was a defender of the murderous seizure of power in Chile by General Pinochet – a bloody coup which I also covered in the same year that I met Borges. Interestingly, Pablo Neruda, the great Chilean poet, died during the first days of that military takeover, less than two years after he himself had won the big prize.

Neruda’s funeral in Santiago was the occasion for a massive public show of opposition against the junta, illustrating the enormous veneration both for him and for writers in that country. Hard to imagine an American writer having such a powerful political influence. In any event, Borges’ defense of the brutal military dictatorship in Chile was too much for the Swedes to stomach and he died without the ultimate writer’s accolade.

However, the Academy did have the stomach in 1964 to award the prize to Jean Paul Sartre, who had defended the Stalinist USSR. Sartre was the only laureate to voluntarily refuse the prize. (Boris Pasternak, who won in 1958, was forced by the Soviet Union to turn it down.)

A refusal is not a mere symbolic gesture. The prize is worth a good deal of money – today eight million Swedish kroner, or roughly $894,000. George Bernard Shaw accepted the prize but refused the money, telling the Swedes to use it to translate August Strindberg into English. Sartre during his lifetime refused to accept any literary awards, on the grounds that he didn’t want a prize to compromise his independence. He also specifically deplored the Academy’s tendency to offer the prize only to Western writers and anti-Communist emigres, rather than to revolutionary writers from the developing world; authors he described as spokespeople for the “least favored” and unjustly treated among us. (At that time only one person from the so-called Third World had ever won the prize: Rabindranath Tagore of India in 1913).

W H. Auden, one of the greatest 20th century poets in the English language was another also-ran. Auden was said to have been turned down by the committee because he made errors in a translation of a book by Dag Hammarskjold, a Nobel Peace prize winner. One of the “errors” may have been Auden’s suggestion that Hammarskjold was homosexual – like Auden himself.

But perhaps the ethical low point in the awards, until last year, came just a year after I interviewed Borges. In 1974, the finalists were Graham Greene, Vladimir Nabokov, and Saul Bellow. All were passed over for a joint award to Eyvind Johnson and Harry E. Martinson, both Swedes and both Nobel judges AT THE TIME. A professor at Uppsala University told a Stockholm newspaper that this was more than suspicious. “Mutual admiration is one thing,” he said, “but this smells almost like embezzlement.”

Greene and Nabokov never won though Bellow did, two years later. Nor did Orwell, or Roth, or Updike, or James Baldwin, or any number of other authors who have enthralled countless readers. They never got the call to make the trip to Stockholm. Poor Marguerite Yourcenor one year did get two telephone calls in the middle of the night from Sweden telling her that she did NOT receive the prize. Never did, either.

Some have seen in this list of snubs a pronounced anti-Americanism. In 1997, for example, Salman Rushdie and Arthur Miller were favored to win the Nobel Prize, but both were dismissed on the account that they would have been “too predictable, too popular.” Miller was never again considered. Now, of course, it’s too late, though his fatal popularity goes on being proven night after night on stages all over the globe.

The bias against Americans was actually made explicit in a 2008 statement by Nobel jurist Horace Engdahl. He sniffed that: “The US is too isolated, too insular. They don’t translate enough and don’t really participate in the big dialogue of literature. That ignorance is restraining.”

This seems an incredibly provincial statement. Who is truly insular when you realize that in 118 years the prize has been given to exactly 3 Japanese, 2 Chinese and 2 Indians (counting Naipaul, who never lived in India)? Seven people representing more than one-quarter of the human race. Who is participating in the big dialogue of literature when women, most of the readers and probably a majority of writers in the US and Europe, have won fewer than 10% of the Nobel prizes in literature? Who is out of touch when only 12 Americans, writing in the world’s largest book market, have ever been anointed?

And finally, how in the world did Bob Dylan overcome that peculiar American insularity, with songs and lyrics that maybe every sentient being on earth has heard?

So, perhaps we’d be wrong to take this particular literary distinction too seriously. I rather like this story told by Nadine Gordimer in her acceptance remarks in 1991: When the six-year-old daughter of a friend of hers overheard her father telling someone that Ms. Gordimer had been awarded the Nobel Prize, the little girl asked whether she had ever received it before. He replied that the Prize was something you could get only once. Whereupon the young girl thought a moment and said, “Oh, so it’s like chicken-pox.”