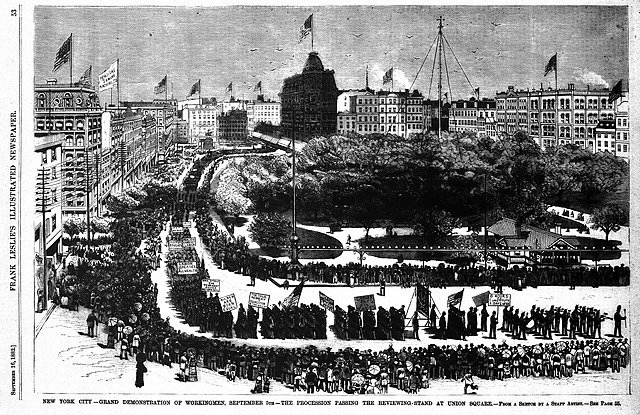

Despite the challenges facing a nascent labor movement, its historic 1882 parade was an obvious success.

-

August/September 1982

Volume33Issue5

On the morning of the first Labor Day, a century ago, William G. McCabe, who was riding downtown to lead a workmen’s parade through the streets of New York City, found himself in a philosophical frame of mind: he was prepared for the worst kind of failure and convinced that whatever happened could only be for the better. Although McCabe was the grand marshal, the preparations had been made by a committee, and he thought the arrangements were “almost a case of suicide.”

“Nevertheless,” he wrote fifteen years later, “I had determined there would be a parade even though I paraded alone.” McCabe had promised that the parade would begin at ten o’clock sharp, but when he dismounted from his horse at his grand marshal’s headquarters just across the street from City Hall at eight-thirty on the calm, clear Tuesday morning of September 5, 1882, he found nothing ready. Even his own union, Local No. 6 of the International Typographers, which had promised not only to march but to provide a band as well, had not managed to field a single member. McCabe had to go himself to the union office nearby and persuade twenty-five or thirty printers to turn out. By nine o’clock about thirty or forty men of the Advance Labor Club of Brooklyn had arrived, and McCabe mustered his first division, only eighty strong, in the shade of the post office, at the south end of City Hall Park.

“Hundreds of men who could find no work to do were standing about having great fun at our expense,” he recalled, “and some of the more serious-minded urged me to give the thing up. ” Instead he set some of his rank and file to haranguing the crowd on the sidewalks and eventually managed to coax another ten dozen recruits to fall in. Still there was no band, and McCabe resigned himself to leading “a straggling mob” of no more than two hundred men. Then, just as the hands of the City Hall clock approached the hour of ten, McCabe saw “faithful old Matt Maguire,” the secretary of the organizing committee, come running across the park. Two hundred members of the jewelers union were on their way from Newark, he said; they would arrive any minute.

For McCabe “it was the first gleam of light in what threatened to be an awful day to me.” In a few minutes he heard the sound of Voss’s Military Band of Newark playing “When I First Put This Uniform On,” from Patience , the latest Gilbert and Sullivan operetta. As McCabe recalled, “Never did music sound sweeter to me.” Soon the jewelers and their band rounded a corner onto Broadway; McCabe deployed his twoman staff and his escort of six mounted policemen. “I gave the order to move, and up Broadway we went.”

McCabe was not the only one who had his doubts about how the day would go. From the outset a number of skeptics within the nascent labor movement had questioned whether workingmen were capable of putting on a successful picnic, let alone a demonstration of several thousand marching men. The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions, which later became the American Federation of Labor, was less than a year old but already confirmed in its down-to-earth creed: higher wages and a shorter workday. Its rival, the Order of the Knights of Labor, was still more interested in Utopian visions of social reform. Around New York, members of the thirteen-year-old Knights of Labor refused to identify themselves for fear of losing their jobs. Both the Advance Labor Club and the Newark jewelers union, which marched in McCabe’s vanguard, were pseudonyms for local assemblies of the Knights. Nevertheless, the New York, Brooklyn, and New Jersey Knights wanted to be active leaders of the labor movement, so they formed an umbrella organization for workingmen of the metropolitan area, which they called the New York Central Labor Union.

McCabe, who was the delegate from his printers local, reported that one Sunday afternoon Matthew Maguire, the secretary of the Central Labor Union, suggested that all labor organizations in the vicinity of New York be invited to make “a public show of organized strength.” Indeed, the minutes of the meeting held on Sunday, May 14,1882, at Science Hall, 141 East Eighth Street, record that a plan was presented “by a delegate for holding a monster labor festival in which all workingmen could take part early in September, the proceeds to be devoted to the benefit of all unions taking part.”

The proposal caught on quickly. On May 21 a committee of five was appointed to find a site for a picnic. Two weeks later the committee reported that it had reserved Elm Park, at Ninth Avenue and Ninety-second Street, for September 5. The biggest beer garden in the city, Elm Park was owned by Louis Wendel, a rising saloonkeeper and politician, who put up a sum of money to pay for printing fifty thousand 25-cent picnic tickets. These were distributed to the constituent unions on the understanding that they would keep the money from the tickets they sold, but that proceeds from sales at the gate would go to the Central Labor Union.

The parade preparations did not go so smoothly. McCabe complained that although “the dauntless Maguire” chose the route and specified where each organization was to assemble, nine-tenths of the units named in the order of march had never declared whether they would in fact appear. “The whole thing certainly looked dubious,” he wrote, “but I filled the reporters full of information, incubated in the recesses of my imagination, which they printed, giving out the impression that our parade was going to be a stupendous affair.”

With equal audacity the Central Labor Committee issued a last-minute proclamation, declaring the next day a holiday in the name of fifty-six member organizations representing almost one hundred thousand men. The program for the day was published in an eightpage newspaper called The Central Labor Journal . McCabe forecast a turnout of twenty thousand marchers and trumpeted a final call to arms: “We are entering a contest to recover the rights of the workingmen and secure henceforth to the producer the fruits of his industry. Our demonstration tomorrow is the review before the battle. … The greater it is the more thoroughly will the enemy be disheartened and the easier will our victory come. Let no man shirk, let none desert, let everyone be where his presence will contribute to the common purpose.”

It was sheer bravado. The plan was to form in three divisions, with the head of the parade more than a mile away from its tail. But when McCabe ordered the first division to march up Broadway, he still had not heard whether there was anybody to march in the second, which was supposed to join him at Fourth Street with organizations from the West Side, or in the third, which was to join at Waverly Place with East Side organizations. He could count on only his little vanguard of about four hundred men, and Voss’s thirty-five-piece band.

“What a march that was!” McCabe later said. “I think the driver of every vehicle that could possibly do so crossed our line.… Several times I protested to the officer in charge of the police squad, but he and his men seemed to regard the affair as a circus, and would or could do nothing …”

But it was not the obstructive teamsters or “the blue-coated humorists” who most bothered McCabe: “It was the heartless guying and insults of the working people on the sidewalks and the men and women workers in the windows of the factories along Broadway that cut me. The people whom the Central Labor Union wished to lift up; these factory workers with long hours or small wages; these men who were on the sidewalks looking at our parade because they had no work at any wages—their taunts and jibes and insults were unbearable.”

Then, after a mile of this, something happened. Four hundred members of the bricklayers union swung into the parade from a side street, and at their head marched a special squad of forty, dressed in white bricklayers’ aprons, who formed a protective screen around the head and flanks of the column. According to one account, each man carried a chunk of brick in his pocket. At this point, McCabe reported, Roundsman Gannon, the commander of the police escort, “became proportionately more respectful. ”

From then on, it seemed that every side street was filled with workingmen in rank and file, with bands and floats, waiting to join the parade.

While McCabe was marching up toward Union Square, the Sixth National Assembly of the Knights of Labor was meeting there, and Terence Powderly himself, the most distinguished labor leader in the country, stood ready to review the parade along with most of the 76 delegates who represented the union’s 42,517 members.

At eleven o’clock Grand Marshal McCabe came into view “on a fine horse,” saluted the assembled dignitaries, and then joined them on the stand to review his troops. “Nearly all were well clothed,” The New York Times reported, “and some wore attire of fashionable cut. The great majority smoked cigars …”

The decorative masons turned out in yellow aprons; the journeymen horseshoers wore “gold-fringed silk aprons of various colors, in which red horseshoes were woven”; most of the longshoremen were in checkered jumpers; and the German framemakers union arrived with “a number of tremendously tall fellows with clay pipes clenched in their teeth and beaver hats on their heads, huge axes on their shoulders and thick leather aprons over their thighs.” One spectator wrote that “the whole thing gave a faint suggestion of the gathering of guilds in past centuries.”

The bricklayers marched behind wagons bearing arches of brick, the pianomakers had a wagon with a piano, “upon which a pianomaker enthusiastically played,” and the framers brought a wagon with a desk and other furniture. At last there were enough bands to provoke the Herald into grumbling that if the working men could afford them all “just for a day’s fun they should reflect whether, after all, they are as badly off as they imagine. ”

It took about forty-five minutes for the parade to pass the reviewing stand. The Sun estimated the number of marchers at 12,500 men; the World , at 14,000; the Irish World , at between 15,000 and 20,000. McCabe put it at “nearly 4,000 men,” a body more likely to be able to pass in review in forty-five minutes.

None of the contemporary accounts used the expression Labor Day, nor did the Central Labor Union’s handbill, which described it as a “Demonstration of Labor, Mammoth Festival, Parade and Pic-Nic.” Powderly said he first heard the expression on the reviewing stand: “During the time that the various organizations were passing the Grand Stand at Union Square, Robert Price, of Lonaconing, Md., turned to the General Worthy Foreman of the Knights of Labor, Richard Griffiths, and said, ‘This is Labor Day in earnest, Uncle Dick.’ Whether that was the first time the term had been used is not known, but the event was afterwards referred to as the Labor Day parade. ”

The remainder of the march, across Seventeenth Street and up Fifth Avenue, symbolized the economic antipodes of the times. Hundreds of men who labored ten to twelve hours, six days a week, for the standard daily wage of two dollars, tramped through the most ostentatious corridor of wealth and power in America. They passed August Belmont’s house; they trudged on past the tonish Brunswick Hotel; past the uptown Delmonico restaurant; past the elegant new Union League Club; past the mansion of Vincent Astor. Mrs. Astor—along with many of her millionaire neighbors—was in Newport for the season. Nevertheless, if the consciousness of capitalism was not penetrated, its precinct was, by a procession that included a large delegation of the Progressive Cigarmakers Union, wearing red ribbons, bearing red banners, led by a red-sashed official, and accompanied by the Socialist Singing Society under a red flag.

The parade ended at Forty-second Street and Sixth Avenue, a little more than three miles from McCabe’s starting point at City Hall and just a step away from the nearby station of the Metropolitan Elevated Railway, which would carry the celebrants to the picnic grounds.

At Elm Park, women and children were admitted free. McCabe arrived shortly after one o’clock with his family, confident that there would “be no chance for the rowdies who sometimes disturb picnic parties to make any headway here, for, besides the engagement of ten policemen, there will be 400 policemen of our own people ready to assemble at any point at a given signal.”

Each union chose a picnic area and draped its banners and placards from the branches. Flagpoles of the park flew American, Irish, French, and German flags—but not the British Union Jack. There was a large pavilion with a band playing waltzes and polkas, two choral groups, a pianist, and a music-hall performer. “Swings, electric machines, singing, dancing, impromptu band concerts and many other attractions were in full blast,” wrote one observer, “while an expert drove a thriving trade cutting profiles out of black paper.” According to McCabe, twenty-five hundred people were in the park by two o’clock, twenty-five thousand by seven. “Our parade had awakened the city,” he wrote triumphantly. “What a brotherhood was formed that day! The young people danced and sang, the old people smilingly looked on, and augured on the grand future of labor as the outcome of the day’s good work.”

The picnic made a profit of $230 for the Central Labor Union, including the sum of $4.70 that was recovered from an unidentified member of the organizing committee, after an audit of the accounts at a delegates’ meeting the following Sunday. While that matter was settled peaceably, the meeting almost turned into a donnybrook when one of the printers demanded to know why the Central Labor Journal had been printed in a nonunion shop. Words like scab and lie were flung back and forth. Two delegates clinched, then were pulled apart. “There was great confusion for the next five minutes,” the Sun reported, “until McCabe, who was presiding, took the gavel and pounded loudly.”

But in spite of the bickering, the festival of labor was obviously a success, so much so that two years later, George K. Lloyd, then secretary of the Central Labor Union, offered a successful resolution: “Resolved that the Central Labor Union does herewith declare and will observe the first Monday in September of each year as Labor Day.”

In 1887 the New York State Legislature was still considering a bill to make Labor Day an official holiday when Massachusetts acted, the first state to do so. Twenty-five states were observing Labor Day on one date or another by 1893. The next year, President Cleveland signed an Act of Congress making the day a national holiday. He gave the pen to Rep. Amos J. Cummings of New York, who was the sponsor in the House; Cummings sent it to Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor. The Knights of Labor had long since gone into decline, and Gompers, not Powderly, was labor’s leading statesman.

When Cleveland flourished his pen, the dauntless Matthew Maguire was living in Paterson, New Jersey, where he had become a union organizer and the Socialist Labor party’s candidate for Vice President of the United States. His hometown paper, The Morning Call, loyally protested in an editorial that the pen should have gone to Maguire—he was, after all “the father of the Labor Day holiday.”