In an instant on November 22, 1963, morning in America became mourning in America.

-

Winter 2024

Volume69Issue1

If you are like me of a certain age, you remember exactly where you were, what you were doing, and how you felt when you heard the news 60 years ago: John F. Kennedy, our vibrant, young 35th president had been assassinated in Dallas, Texas.

If, like most Americans, you weren’t yet born, you may not even imagine what it felt like when, in one day, the soaring Sixties, a time of ascending, if cautious optimism–about progress in civil rights and other social issues, about America’s role in the world, its ambitious moon quest, its idealism reflected in the Peace Corps–instantly went into reverse.

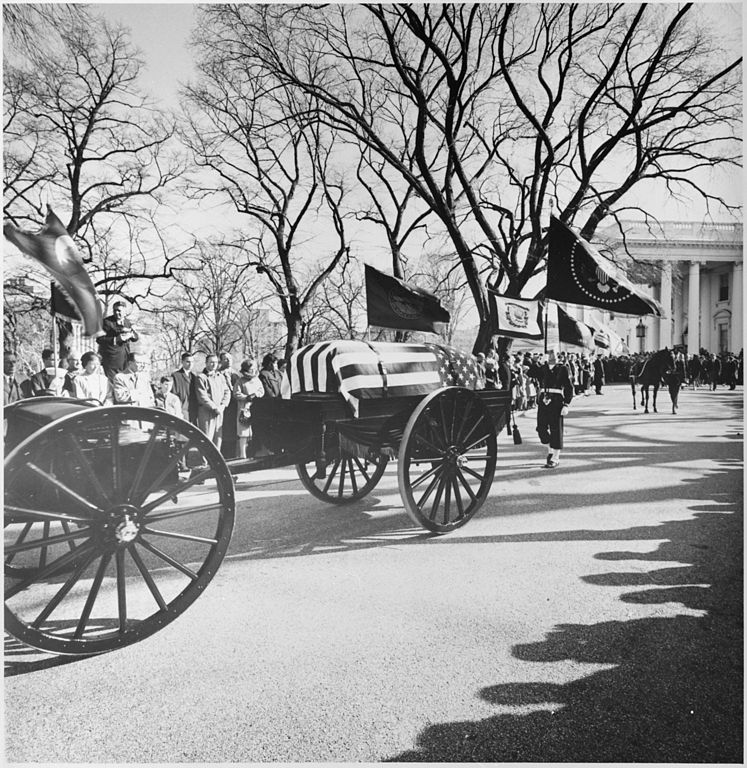

In an instant, morning in America became mourning in America. There were indelible images, seen mostly on black and white television sets: The horse-drawn caisson, carrying the flag-draped coffin moving quietly down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol. The barely three-year-old John F. Kennedy, Jr., standing at attention and saluting the coffin as it passed. The widow Jackie in black, a veil partially covering her face.

The closest similar occasion anyone could recall was 18 years earlier, when Franklin D. Roosevelt, the presidential hero of our parents’ generation, died suddenly of a stroke. There followed a similar, sad procession on Pennsylvania Avenue. I was not quite three. My parents venerated FDR, but I have no recollection. I can only imagine their reaction.

Of the days surrounding JFK’s assassination, I do not have to imagine. From my own perspective six decades later, this is what it was like for me on that day and that weekend, the first of many days in that terrible decade when, once again, hope died.

It was the fall of my senior year at Columbia. I had finally hit my stride academically, after struggling initially to compete academically with the better-prepared preppies. I was a normal 18-year old graduate of a public high school where I’d been a high-ranking honor student, but still woefully unprepared for the academic rigors of an Ivy League education.

It was a Friday at lunchtime when Kennedy was fatally shot while riding in the back seat of an open car in the presidential motorcade. I had just left class or the library when I heard the news. I’d recently been dumped by my college girlfriend, a Barnard sophomore, someone with whom I could no longer commiserate.

But I belonged to a fraternity and lived in the house, a brownstone at 538 114th Street, so that is where I went to share my shock and grief. What I found was itself shocking.

When I returned to my fraternity house, Phi Gamma Delta, across the street from the Columbia campus, I found my conservative brothers wearing Barry Goldwater buttons and holding an “LBJ inauguration party.” I was appalled.

That weekend, the keg party went on as usual, but without a live band, which the campus fraternity council had deemed inappropriate under the circumstances. The following day, a Sunday, I watched the television footage of alleged assassin Lee Harvey Oswald being gunned down by nightclub owner Jack Ruby, giving rise to lingering conspiracy theories.

See "Why Did Rudy Kill Oswald?" in this issue by the

Warren Commission lawyer who investigated Rudy

CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite brought it all to us, a nation not yet siloed by social media.

A regular chapter meeting of my fraternity was scheduled for Monday night, hours after the presidential funeral, which I also watched on a black and white television in my fourth-floor rear bedroom. I said that, if the meeting were held, I would not attend, and bowing to their better instincts, the brothers canceled it. That was my personal protest.

I was never a student activist, but I like to think I did have a social conscience, which asserted itself, if only briefly, after yet another date that should forever live in infamy: November 22, 1963.