The unique political genius of Abraham Lincoln was to navigate carefully and at times conservatively between abolition and the Southern cause until he knew the time was right for radical justice.

-

Spring 2022

Volume67Issue2

Editor's Note: David S. Reynolds is a Distinguished Professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and the author of 16 books. His latest, Abe: Abraham Lincoln in His Times, is an ambitious and wide-ranging biography relating Lincoln to his cultural environment in antebellum America. The book won both the Lincoln Prize and the Abraham Lincoln Institute Book Award. It was chosen among the Top 10 Books of the Year by the Wall Street Journal and was on the Best Books lists of the Washington Post, the Christian Science Monitor, and Kirkus. Prof. Reynolds adapted the following from Abe.

There are many things one can learn from America’s greatest president. In a deeply divided time, keep to the center while sticking with the nation’s core principles if you want to be an effective leader. Don’t insult your opponents. Make the center lively. And don’t forget young voters.

During the 1850s, Lincoln took a middle position on the “isms” of his day. He didn’t fully embrace any of them, but he didn’t distance himself from those who did. He kept his eye trained on the one ism that really counted. In September 1859, he urged the Ohio politician Salmon Chase to do all he could to stop “Douglasism” — the threatened westward spread of slavery. “That ism,” Lincoln wrote, “is all which now stands in the way of an early and complete success of Republicanism.”

Lincoln explained that “the chief effect of Douglasism” was to change the “moral tone and temper” of the American people by inviting them to become indifferent about human rights. All of Douglas’s “reasoning and sentiments,” Lincoln declared, “spring from the view that slavery is not wrong.”

But in arguing that slavery was wrong, Lincoln did not join those who gathered under the moralistic banner of New England Puritanism. He was notably absent from the grand ceremony for the laying of the cornerstone of the National Monument to the Forefathers in Plymouth, Massachusetts, on August 2, 1859. Completed in the 1880s, the eighty-one-foot monument, featuring symbolic statues of Faith, Morality, Liberty, and the like, rooted public morality in the Pilgrims.

“Our life is their life,” one speaker announced to the crowd of five thousand. “From their oppression springs our freedom.” Among the orators that day were the antislavery leaders Salmon Chase, Henry Ward Beecher, John Parker Hale, Henry Wilson, and Francis P. Blair. Letters of support came from other notables. But not from Lincoln.

Nor did he participate in the widespread celebration in the North of the quintessential latter-day Puritan, John Brown, who was executed in Virginia on December 2, 1859, after he and a band of followers raided Harpers Ferry in a bold but doomed effort to spark a slave rebellion that they hoped would lead to the collapse of American slavery.

Lincoln resisted overpraising John Brown because he saw that any violation of the Constitution, real or perceived, threatened the Union. He carefully honed the Republican Party’s argument that the Founders themselves realized the wrongness of slavery and had anticipated its ultimate extinction, and he presented this argument most fully in the landmark Cooper Union Address of February 1860, which Harold Holzer calls “the speech that made Abraham Lincoln president.”

See “The Speech That Made the Man,” by Harold Holzer

Often overlooked cultural factors also contributed to his election. The most important ones can be summed up in three words: Blondin, Barnum, and b’hoys. Charles Blondin was a tightrope performer to whom Lincoln was often compared. Just as Blondin symbolized Lincoln’s effort to remain centered between radicals and conservatives, so Barnum, the master showman of the age, represented the kind of theatrics which found a parallel in the proliferation of images of Lincoln as Abe, the folksy, axe-wielding frontiersman, which were key to his national popularity and election.

Another huge boost came from Lincoln’s success in winning over the b’hoys, a large group of young Americans who had formerly been loyal to his opponent, Stephen Douglas.

Remaining balanced over the falls

In the summer and fall of 1859, the touring thirty-five-year-old French acrobat Charles Blondin (né Jean-François Gravelet) dazzled Americans with his tightrope walks, the most famous of which were his repeated crossings of Niagara Falls. Poised on a hemp rope 200 feet above the roaring, mist-bellowing falls — five hundred thousand tons of water plunging per minute, Lincoln had once calculated — Blondin traversed the 1,100-foot span between the American and Canadian sides as thousands of spectators gasped and cheered. Advancing across the rope, which was steeply sloped because it sagged some 60 feet in the middle, he steadied himself with a balancing bar and performed amazing tricks: somersaults, flips, headstands, monkey crawls, and balancing on a chair. He walked backward, at night, blindfolded, in chains, and on four-foot stilts.

One of Blondin’s most famous feats was walking across the falls with his agent, Henry Colcord, on his shoulders. Another involved his pushing a stove in a wheelbarrow to the middle of the rope, cooking an omelet, and lowering the meal to passengers on the Maid of the Mist observation boat below.

Lincoln found in Blondin a symbol for his centrist position on major issues. Before the Civil War and during it, Lincoln balanced himself between extremes: popular sovereignty and the demand for immediate abolition, Southern and Northern views, and between variegated higher laws and what he and other Republicans saw as the antislavery higher law within the Constitution. He thought that, if he leaned too far in any direction, the nation could fall into anarchy or despotism. With the political and cultural forces around him spinning toward the centrifugal, he provided a solid centripetal counterweight.

Lincoln identified strongly with Blondin. In the summer of 1862, a group of radical antislavery Bostonians visited him in the White House and urged him to aim the war more directly at the abolition of slavery. He greeted the group cordially and listened while its leader read an address that announced that “the government must have a policy” on slavery. After the speech, Lincoln sat back and threw a leg over the corner of a table. He thought for a moment, then asked, “Do you remember that, a few years ago, Blondin walked across a tight rope stretched over the falls of Niagara?” Suppose, he said, that all the nation’s goods and achievements were crammed into a wheelbarrow, and the security and safety of everyone’s home depended on Blondin’s guiding it successfully over the falls.

Lincoln continued, “As he was carefully feeling his way along and balancing his pole with all his most delicate skill over the thundering cataract, would you have shouted to him ‘Blondin, a step to the right!’ ‘Blondin, a step to the left!’ Or would you have stood there speechless, and held your breath and prayed to the Almighty to guide and help him safely through the trial?” The Bostonians got the point and left.

What Lincoln did not tell them was that he had in his drawer a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, which he would announce publicly in September in the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation and then issue in its final form the following January. He had already put into writing the sort of antislavery policy they called for.

The artist Francis Carpenter, who called the Emancipation Proclamation “an act unparalleled for moral grandeur in the history of mankind,” heard Lincoln make a similar remark to a delegation of westerners in 1864. Complaining hotly about the progress of the war, the westerners heard the same story the Bostonians had. Lincoln invited them to imagine all their property transformed into gold and given to Blondin to transport across the Niagara River. “Would you shake the cable,” he asked, “or keep shouting out to him, ‘Blondin, stand up a little straighter—Blondin, stoop a little more—go a little faster—lean a little more to the north—lean a little more to the south.’ No, you would hold your breath as well as your tongue, and keep your hands off until he was safe over.”

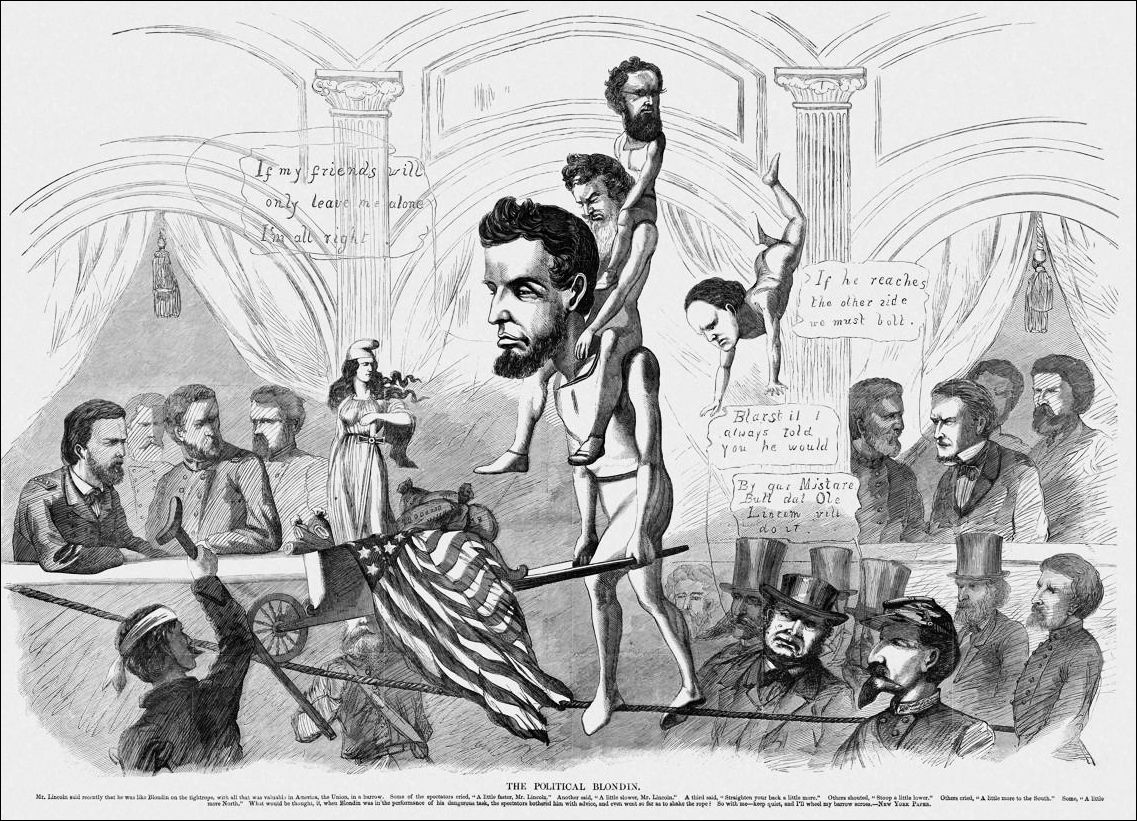

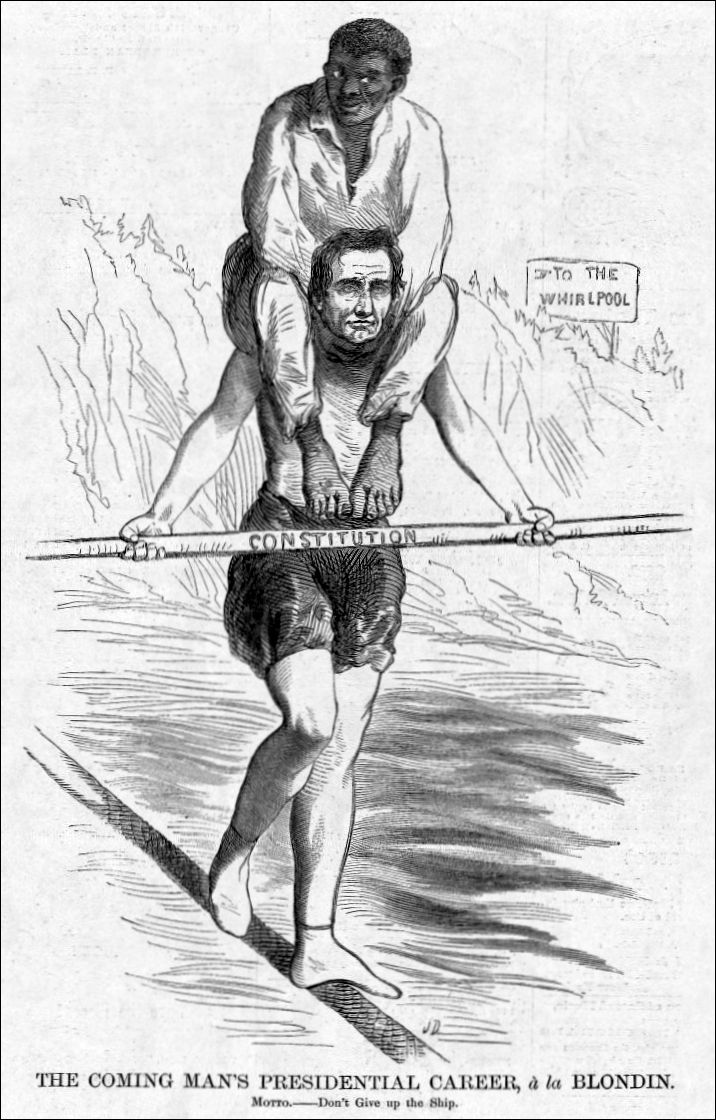

Political cartoonists often made the Blondin comparison. In June 1860, shortly after Lincoln was chosen as the Republican Party’s presidential candidate, the humor magazine Vanity Fair published “Shaky,” picturing a costumed, scared-looking “Mr. Abraham Blondin De Lave Lincoln” walking precariously on a narrow, crooked log, barely keeping his balance because he is holding a pole weighed down by a bag holding a black man in it and with Horace Greeley in the background yelling, “Don’t drop the carpet bag.” The message? Lincoln, as a Republican, faced the challenge of keeping centered on the controversial issues of race and slavery. The same theme informed the cartoon “The Coming Man’s Presidential Career, a la Blondin,” in which Lincoln crosses Niagara with an African American on his shoulders while holding a pole inscribed with the word “Constitution.”

Lincoln’s Blondin-like centeredness galled some radical abolitionists. In 1864, Wendell Phillips complained that Lincoln, who was slow to come out in support of the vote for black people, should be pushed off his tightrope (that is, he must not be reelected). Frustrated by the president’s public silence on African American suffrage, Phillips declared in a speech that “the franchise for the slave” was “indispensable” and “inevitable,” but “there is Blondin — don’t speak to him! He may go over—take care! Mr. Lincoln stands there balanced, with the pole, on a rope. Keep mum, nation!” Impersonating Lincoln, Phillips said, “‘Don’t think I shall go over! Oh, no; I am balanced — balanced even!’” “But the question,” Phillips continued, “is whether he is well balanced with his eye fixed upward. The Abolitionist says to Lincoln — ‘Look up — to justice, of God, to the rights of every man under the law!’ He is looking down at Kentucky, and I tremble for him.”

Phillips had a point. Lincoln focused on keeping border states like Kentucky in the Union, and he was publicly silent on black suffrage until after Appomattox, when he recommended it in a speech (to the disgust of the actor John Wilkes Booth, who was in the audience). Unbeknownst to Phillips, Lincoln had already promoted the black vote in a private letter to the Louisiana governor Michael Hahn. Also, he was waging a relentless war that would lead to a Union victory and the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, which emancipated and gave citizenship rights to black Americans.

Lincoln, therefore, was, to use Phillips’s words, looking up “to justice, . . . to the rights of every man under the law!” But he was cautious about expressing his abolitionist sympathies too strongly, which, he knew, could motivate the slave-holding border states to leave the Union and join the Confederacy. He explained, “I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we can not hold Missouri, nor, as I think, Maryland…. We would as well consent to separation at once, including the surrender of this capitol.”

He had been training for years to be a political Blondin, one who carefully fused progressive public statements with moderate ones. His 1837 announcement that slavery was unjust but that vituperative abolitionists used the wrong means of fighting it; his 1854 Peoria speech, which coupled abolitionism with colonization; his debates with Stephen Douglas, in which he repeated the common idea that blacks were not equal to whites, while also stressing that they merited fair treatment under the Constitution—these are a few of the many instances in which Lincoln tempered radical declarations with conservative ones.

This balanced, Blondin style drew criticism. In 1858, there appeared a pamphlet, Abraham Lincoln! And His Doctrines, Examined and Presented in a Concise Form, from His Own Speeches, which juxtaposed passages from various Lincoln addresses to suggest that he often contradicted himself. In the sarcastic words of the pamphleteer, his speeches revealed “Mr. Lincoln an Advocate of Negro Equality and Negro Citizenship,” and, simultaneously, “Mr. Lincoln Opposed to Negro Equality” and “Opposed to Negro Citizenship”; “Mr. Lincoln Will Not Vote to Admit a State with Slavery,” and he “Will Vote to Admit a State with Slavery”; he was “Not in Favor of Interfering with Slavery Where It Now Exists,” and he wants it “To Be Put on a Course of Ultimate Extinction.”

Such apparent incongruities in Lincoln’s thinking bring Walt Whitman to mind, who in 1855 wrote, “Do I contradict myself? / Very well then . . . I contradict myself; / I am large . . . I contain multitudes.” Whitman’s contradictions reflected a democratic poet’s expansive goal of putting all of American experience onto the page. Lincoln’s, in contrast, show him hovering around the center in an effort to keep himself and his nation in balance in a politically unstable time. Just as a tightrope artist, responding to natural conditions like wind, leans slightly one way or the other to keep on the rope, so Lincoln tilted right or left according to his sense of what would be most effective in advancing his progressive agenda. During the debates with Douglas, for instance, he made his most conservative statements on race and slavery while speaking in the Southern section of Illinois and his most forward-looking ones in the state’s Northern region.

His Blondin approach to politics helps explain his rise to the leadership of the Republican Party. In the jockeying among possible candidates for the party’s 1860 presidential run, he stood for moderation. When Ohio Republicans drafted a platform calling for the repeal of “the atrocious Fugitive Slave Law,” Lincoln advised Salmon Chase to oppose it, explaining that such a plank would “explode” the forthcoming Republican National Convention, where its supporters and its opponents would “quarrel irreconcilably.”

As much as Lincoln hated the Fugitive Slave Act, he reminded Chase of Article IV, Section 2, the Constitution’s so-called Fugitive Slave Clause. Lincoln had similar advice for Schuyler Colfax of Indiana, whom he warned to avoid “apples of discord” that might disrupt the party. Lincoln counseled, “We should look beyond our noses; and at least say nothing on points where it is probable we shall disagree.”

The period between the fall of 1858, when he had the debates with Douglas, and November 1860, when he was elected president, saw him accomplishing an especially difficult Blondin feat. He was both self-reliant and, to use his own words, controlled by events. He exercised aggressive individual effort while responding sensitively to outside forces.

The strongest force was the nation’s response to the militant abolitionist John Brown, who had taken on mythic status in much of the North because of his antislavery activities in Kansas Territory, where in 1856, he and his small band of followers had defeated larger military units that tried to turn Kansas toward slavery. The Brown party’s slaying of five proslavery settlers on Pottawatomie Creek in May 1856, in response to numerous atrocities committed by the proslavery side, was part of the spiraling cycle of violence in Bleeding Kansas.

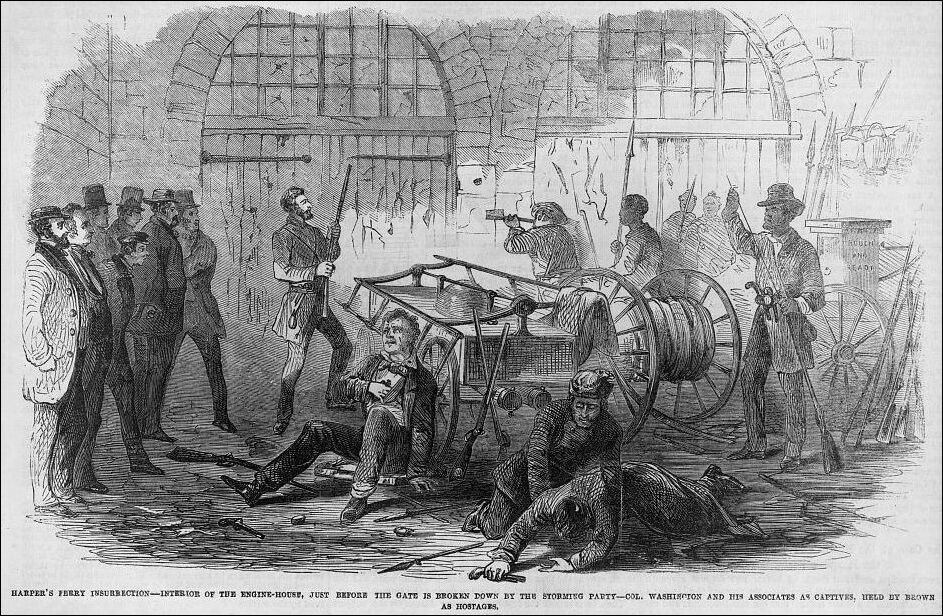

Among some antislavery Northerners, Brown rose to virtual sainthood after his October 1859 assault on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, when he and eighteen followers invaded the federal arsenal there in an attempt to spark a slave rebellion that he hoped would lead to the fall of slavery. After a battle in which seventeen were killed, Brown and six followers were captured, tried, and hanged. Though found guilty of treason, murder, and inciting a slave rebellion, Brown, during his weeks in jail while awaiting execution, exhibited a selfless devotion to the nation’s millions of enslaved blacks that won the admiration of many leading Northerners. Henry David Thoreau compared Brown to Jesus Christ.

Emerson, similarly, called him “that new saint” who would “make the gallows glorious like the cross.” William Herndon wrote that Brown “was good and great and is immortal—will live amidst the world’s gods and heroes through all the infinite ages.”

John Brown worship swept the North, leading to the stirring “John Brown’s Body,” the Union army’s favorite marching song, reworded by Julia Ward Howe as “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

The veneration of John Brown put Republicans in a tricky position. If they praised him without qualification, they laid themselves open to the charge of supporting an armed invader of the South who had implacably observed his own higher law. But to reject him altogether was to alienate the growing number of Northerners who followed intellectual leaders like Emerson and Thoreau in revering the martyr of Harpers Ferry. And so most Republicans took an ambivalent position, praising Brown’s antislavery motives but disapproving of his violent tactics.

Despite their caution, Republicans could not escape being accused for Harpers Ferry. Shortly after the raid, one of Lincoln’s advisers, Charles H. Ray, recognized the vulnerability of the Republicans. He wrote Lincoln, “We are damnably exercised here about the effect of Old Brown’s wretched fiasco in Virginia, upon the moral health of the Republican party! The old idiot—The quicker they hang him and get him out of the way, the better.”

Responding sensitively to the extreme reactions to Brown, Lincoln did another stellar tightrope walk. In December 1859, the month Brown was executed, Lincoln gave two speeches in Kansas in which he presented a mixed view of Brown. He said that the abolitionist warrior had shown “rare unselfishness, great courage,” and “he agreed with us in thinking slavery wrong.” But, he added, Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry had been futile and lawless, and nothing could “excuse violence, bloodshed, and treason.” When proslavery politicians continued to ramp up their accusation that the Republican Party was responsible for Harpers Ferry, Lincoln became even more guarded. In his February 1860 speech at Cooper Union in New York, he declared that the Republicans had nothing to do with Brown, who in fact had rejected politics and acted as a vigilante abolitionist with a quixotic plan for ending slavery.

Lincoln’s public distancing of himself from Brown prior to the election failed to impress Southerners. They sensed that he hated slavery just as much as John Brown did. They were right, although he wanted to fight it through the electoral process, not through violence. During the 1860 presidential race, a leading Southern magazine remarked sourly that, if Lincoln won the election, the White House would be soon occupied by “a vulgar partisan of John Brown.”

Early in his presidency, Lincoln continued to keep steady on his tightrope. Although he hated slavery and yearned for its abolition, his fear of losing the border states and enraging northern Democrats contributed to his early avoidance of waging a war for emancipation, which, he said, “would be equivalent to a John Brown raid, on a gigantic scale.”

During the Civil War, Lincoln was pressured from the left by abolitionists, who wanted him to move more speedily against slavery, and from the right by the border states and by Northern conservatives, who considered him too radical. And so, he stayed on his tightrope. For example, in the weeks just before September 22, 1862, when he issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which he knew would shock moderates, he used preparatory ploys to appease them. One was his proposal of voluntary emigration to a delegation of blacks who visited the White House in August. Another was a public letter to the editor Horace Greeley (who had complained about there being no emancipation proclamation) in which Lincoln said he wanted above all to save the Union, with or without slavery. A third was his comment to a group of Chicago ministers that an emancipation proclamation would have no effect in the South and would therefore be as futile as when a pope had once issued an edict against a comet.

By 1864, the third year of the war, he was prepared to shift to the left. Positive references to John Brown now appeared in his discussions of war strategy. On August 19, Lincoln met with Frederick Douglass in the White House and asked him to organize “a band of scouts, composed of colored men, whose business should be somewhat after the original plan of John Brown, to go into the rebel States, beyond the lines of our armies, and carry the news of emancipation, and urge the slaves to come within our boundaries.” This was Brown’s Subterranean Pass Way on a grand scale. Douglass eagerly accepted the assignment, which, as it turned out, was canceled after news of the Union victories came the next month.

In the Second Inaugural address, delivered on March 4, 1865, Lincoln used appeals to the Bible and righteous anti-slavery violence that were strongly reminiscent of the language of the Calvinistic Brown—so much so that a leading New York newspaper called the speech “a prose parody of ‘John Brown’s Hymn’ from the lips of its chosen Chief Magistrate.”

But even in this militant speech, Lincoln remained on his tightrope. Focused, elegantly balanced, suggestive in every phrase, the Second Inaugural assigned antislavery meaning to the war without sounding partial or smug. Lincoln avoided one-upmanship in his rhetoric. He did not speak for one side. He made no mention of South or North, Democrat or Republican. He talked about “all” and about the “parties” involved. Four years ago, “all thoughts” were turned toward war; “All dreaded it—all sought to avert it.” But “the war came,” like an inexorable force. Even in describing the war itself, Lincoln used the rhetoric of unity: both sides expected a short war, both sides prayed to the same God, and the prayers of neither were fully answered. His compassionate outreach culminated in the opening words of his closing paragraph: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right.” These flowing phrases, made resonant by the use of parallelism, are fixed in American memory and literature.

With his wisely calibrated rhetoric and his democratic expansiveness, President Blondin succeeded in shepherding the nation through its worst crisis. Lincoln’s expert balancing and firm devotion to principle stand as a master lesson in how political genius, combined with integrity, can be directed toward the advancement of justice and human rights.