In his Second Inaugural Address, Abraham Lincoln embodied leading in a time of polarization, political disagreement, and differing understandings of reality.

-

Winter 2023

Volume68Issue1

Editor’s Note: Jon Meacham is a renowned presidential historian and Pulitzer Prize-winning author whose latest books include The Soul of America and And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle, from which this essay was adapted.

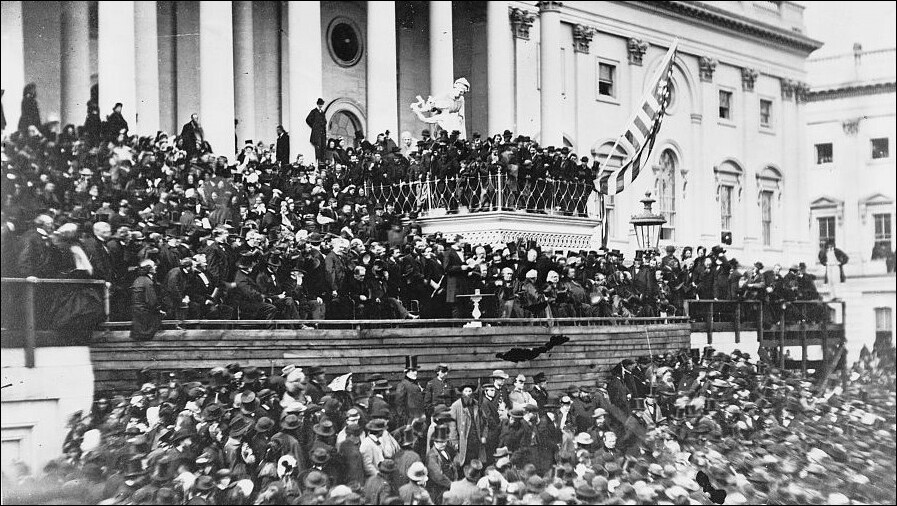

The day of Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration, gales of wind and sheets of rain roared across the Potomac and struck Washington, destroying trees and soaking the city. Pennsylvania Avenue was a sea of mud, thick and soggy. It had already been raining for two days running; the Army Corps of Engineers considered constructing pontoon bridges to make the city’s main thoroughfare passable. A foot could sink as deep as a knee in the ooze.

The wet wartime capital was at once festive and solemn. Willard’s Hotel, next door to the Treasury Building, was packed with 1,008 guests, and The Daily National Republican reported that twelve hundred inauguration-goers had swarmed the hotel’s dining tables. “The other hotels in the city were also full, not being able to accommodate another boarder,” the newspaper wrote.

What the journalist Noah Brooks, an intimate of President Lincoln’s, recalled as the “dark and dismal” weather improved slightly as the crowds slogged to the Capitol for the inaugural ceremonies. Completed in the war years, the building’s cast-iron dome loomed above Washington. The president had made sure that the project continued even as the struggle unfolded. Workers, many of them enslaved until Lincoln had signed the bill for emancipation in the District of Columbia in 1862, stayed on the job.

“It seemed a strange contradiction to see the workmen...going on with their labor,” The New York Times had written, “the click of the chisel, the stroke of the hammer” amid “the tramp of the battalions drilling in the corridors.” Lincoln understood the significance of perseverance. “If people see the Capitol going on,” he had said, “it is a sign we intend the Union shall go on.”

And it had. Now, Lincoln stood again where he had stood four years before, at the East Front of the Capitol. Hundreds of thousands of Americans who had been alive on March 4, 1861 were dead, slain by one another’s hands. Innumerable others were wounded and maimed in body and in spirit. Everything had hung in the balance since Fort Sumter. “We are now on the brink of destruction,” Lincoln had said after the late 1862 Union defeat at Fredericksburg. “It appears to me the Almighty is against us, and I can hardly see a ray of hope.”

Until victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in the summer of 1863, the war had seemed lost. Even afterward, the president had expected to lose reelection in 1864. Now, in the late winter of 1865, Union forces were poised for ultimate victory. And at last, slavery was in its final months of life in the United States.

Driven by the convictions that the Union was sacred, and that slavery was wrong, Lincoln was instrumental in saving one and in destroying the other, expanding freedom and preserving an experiment in popular government that nearly came to an end on his watch. In him we can engage not only the possibilities and the limitations of the presidency, but the possibilities and limitations of America itself.

All anyone knew of the second inaugural speech before its delivery was that it would be pithy. “The address will probably be the briefest one ever delivered,” The New York Herald reported in a preview. Lincoln, who had written every word of it himself, had had the speech printed in two columns. He would read it, with his spectacles, standing behind a small table fashioned from cast-iron pieces left over from the construction of the Capitol dome.

To Frederick Douglass, who braved the mud to hear the president in the open air, Lincoln’s ensuing address “sounded more like a sermon than a state paper.” In fact, it was both.

Lincoln rose to deliver his address in what observers thought was a “clear, resonant” voice. The previous year, in an unsettling military hour around the time of the Wilderness Campaign, Lincoln had wondered aloud: “Why do we suffer reverses after reverses? Could we have avoided this terrible, bloody war? Was it not forced upon us? Is it ever to end?”

Now, he would venture some answers to his own anguished questions.

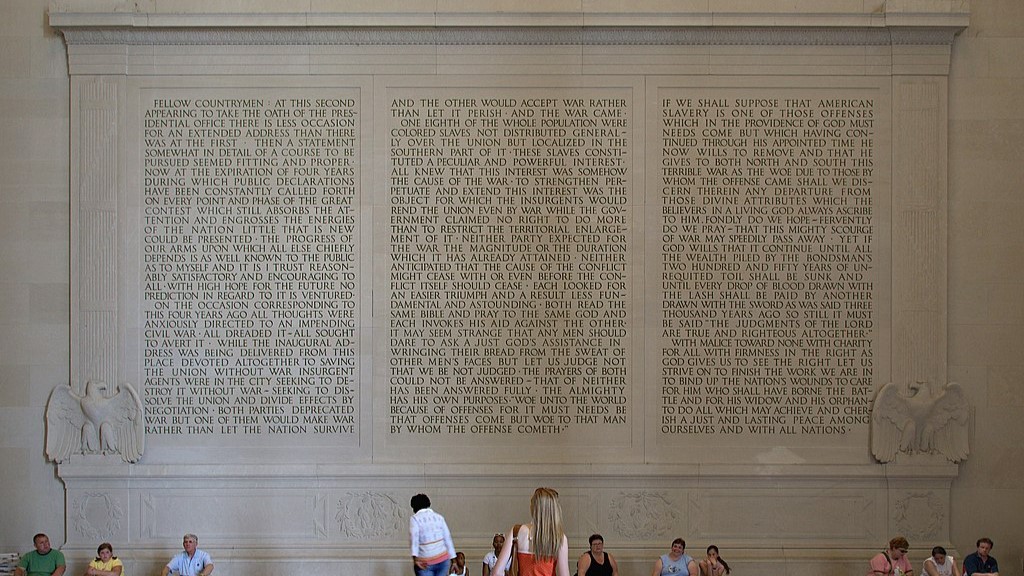

“Fellow countrymen,” Lincoln said, “at this second appearing to take the oath of the presidential office, there is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first. Then, a statement, somewhat in detail, of a course to be pursued, seemed fitting and proper.”

His task today was less about how the nation must move forward than about why he believed the war had been fought, and what it meant. He had begun his presidency with a brief on secession and Union — a brief that had included support for a constitutional amendment that would have banned the federal government from abolishing slavery where it existed at the time. He was opening his second term with a searching statement about human nature, the relationship between the temporal and the divine, and the possibilities of redemption and of renewal.

Lincoln acknowledged that mortal powers were limited. “Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish,” he said. “And the war came.”

The gulf between North and South was so profound, so unbridgeable, that only the clash of arms could decide the contest between freedom and bondage. In a speech that stipulated the ambiguity of the world, Lincoln was unambiguous about why the war had come: slavery. “One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it,” the president said. “These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war.” There was no escaping this central truth.

Lincoln turned to the perils of self-righteousness and self-certitude, North and South. “Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God,” he said, “and each invokes His aid against the other.” Then the president rendered a moral verdict: “It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged.”

In speaking of the strangeness of profiting from the labor of others — a subtle but unmistakable indictment of slave owners — the president drew on the third chapter of the Book of Genesis: “In the sweat of thy face,” the Lord commanded, “shalt thou eat bread.” Adam and Eve are being expelled from the Garden of Eden; the whole structure of the world as we know it was being formed in this moment. To work for one’s own wealth, rather than taking wealth from others, was the will of God.

Lincoln had come to believe that the Civil War might well be a divine punishment — a millstone — for a national sin. The president hoped the strife would soon be over, and the battle won. “Yet,” Lincoln said, “if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, ‘the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.'”

To Frederick Douglass, “these solemn words...struck me at the time, and have seemed to me ever since to contain more vital substance than I have ever seen compressed in a space so narrow.”

Lincoln once said that “the author of our being, whether called God or Nature (it mattered little which), would deal very mercifully with poor erring humanity in the other, and, he hoped, better world.” Until then, “poor erring humanity” was charged with making its words and work acceptable in the sight of a God who had enjoined humankind to love one another as they would be loved.

That is where Lincoln left the matter in his peroration on Saturday, March 4. “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations.”

His speech done, Lincoln turned to Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase for the oath of office. The sun came through the clouds. “It made my heart jump!” the president recalled of the breaking light.

The journalist and friend of Lincoln, Noah Brooks wrote that this “was just superstitious enough to consider it a happy omen.” A Black man who worked at the Washington Navy Yard, Michael Shiner, recorded the moment in his diary: “The wind ceas[ed] blowing, the rain ceased raining and the Sun came out and it was as clear as it could be.”

Hated and hailed, excoriated and revered, Abraham Lincoln served as president of the United States in an existential hour. Other presidents have been confronted with momentous decisions — of war and peace, of life and death, of freedom and power. It was Lincoln’s lot to adjudicate whether the nation would, in his phrase, remain “half slave and half free” – and whether the American experiment would survive the treason of a rebellious white South that put its own interests ahead of the Union itself.

The issue was not only political and economic. It was also religious and cultural. The slaveholding South believed it had God and history on its side. The face of the Union, the possibilities of democracy, and the future of slavery, then, were the stakes of a war that Abraham Lincoln chose to wage to total victory — or to defeat.

A president who led a divided country in which an implacable minority gave no quarter in a clash over power, race, identity, money, and faith has much to teach us in a twenty-first-century moment of polarization, passionate disagreement, and differing understandings of reality. For, while Lincoln cannot be wrenched from the context of his particular times, his story illuminates the ways and means of politics, the marshaling of power in a democracy, the durability of racism, and the capacity of conscience to help shape events.

For many Americans, to see Lincoln whole is to glimpse ourselves in part — our hours of triumph and of grace, and our centuries of failures and of derelictions. This is why his story is neither too old nor too familiar. For, so long as we are buffeted by the demands of democracy, for, so long as we struggle to become what we say we already are — the world’s last, best hope, in Lincoln’s phrase — we will fall short of the ideal more often than we meet the mark.

It is a fact of American history that we are not always good, but that goodness is possible. Not universal, nor ubiquitous, not inevitable — but possible.

Excerpted from AND THERE WAS LIGHT by Jon Meacham, published by Random House, a division of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2022 by Jon Meacham. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.