The Nazis had stolen many of the recovered works from prominent Jewish collectors, raising lingering questions of restitution.

-

September/October 2021

Volume66Issue6

Editor's note: Charles Dellheim teaches history at Boston University. His recent work has focused on the role of Jews in modern culture. In Brandeis University Press’s Belonging and Betrayal: How Jews Made the Art World Modern, excerpted here, Dellheim offers an historical perspective on Nazi art looting by telling the story of a circle of art dealers, collectors, and critics who became pivotal figures in the art world.

On May 3, 1945, a man stood outside the old Carthusian monastery of Buxheim, about 90 kilometers to the north of Munich. The white-walled and red-roofed structure dated back to the 15th century and later had been rebuilt in the Rococo style. The man was squarely built, though not tall. He may have had more heft and less hair than during his student days, but he was more intense, resourceful, and determined than ever. He had not come to the monastery to study its architectural forms or famous decorative carvings, although he would have been at home doing so. Nor had religious impulse driven the man there.

The man was on a mission rather than a pilgrimage. Cleveland-born, Harvard-educated, just shy of forty, Lieutenant James Rorimer was a “Jewish gentleman,” as army intelligence put it and the Curator of Medieval Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, whcre he was in charge of the new Cloisters museum. His first tour of Europe a quarter century before had been entirely different than the present one: before going off to college, he had studied art at the École Gory in Paris and traveled in Germany, the land of his paternal ancestors, although his interior designer father had changed the family name from Rohrheimer in 1917 as anti-German prejudice mounted with America’s belated entry into the First World War.

Rorimer recruited powerful supporters in the art world: among them were Paul Sachs, his Harvard mentor, director of the Fogg Museum and scion of the Goldman Sachs financial dynasty; Robert Lehman, another art-loving heir to a German-Jewish banking family (who later donated a magnificent wing to the Met); and John D. Rockefeller Jr., whose $10 million donation had made the Cloisters possible. Their combined clout pushed the Army into giving him another look. In May 1943, he was allowed to enlist as a private.

Rorimer was tapped soon after—with some help from Sachs, whose reach extended from Cambridge to New York to Washington, DC—for a more suitable task. He joined the newly constituted Monuments, Fine Art, and Archives (MFA & A) section of the US Army as a G-5 (Military Government) Specialist Officer. His comrades were mainly art historians or museum curators.

“Here I have the job of jobs as far as my background and desire are concerned,” Rorimer wrote to Sachs from liberated Paris on December 10, 1944. His mission was initially to safeguard historic structures threatened by, or damaged in, battle. In the wake of D-Day, though, the focus shifted to hunting down an unknown quantity of works of art that the Nazis had despoiled as they conquered, occupied, and ransacked one country after another on the Continent.

This was why Lieutenant Rorimer had come to the monastery of Buxheim. As the Monuments Specialist Officer for the US Seventh Army, he had followed the troops as they battled their way through German territory, vanquished the once formidable but now much weakened Wehrmacht, and took control of one village and town after another as the Third Reich collapsed around them.

When Lieutenant Rorimer arrived at Seventh Army Headquarters, he joined forces with Corporal John D. Skilton, aged 36, who was awaiting his own commission. Skilton was delighted to find that he would be working with an old friend he had known from the museum world and with whom he had been stationed, for a time, in England.

In an office at Military Government Headquarters, they affixed maps to the walls and employed colored pins to mark the known and suspected locations of German repositories of stolen art.

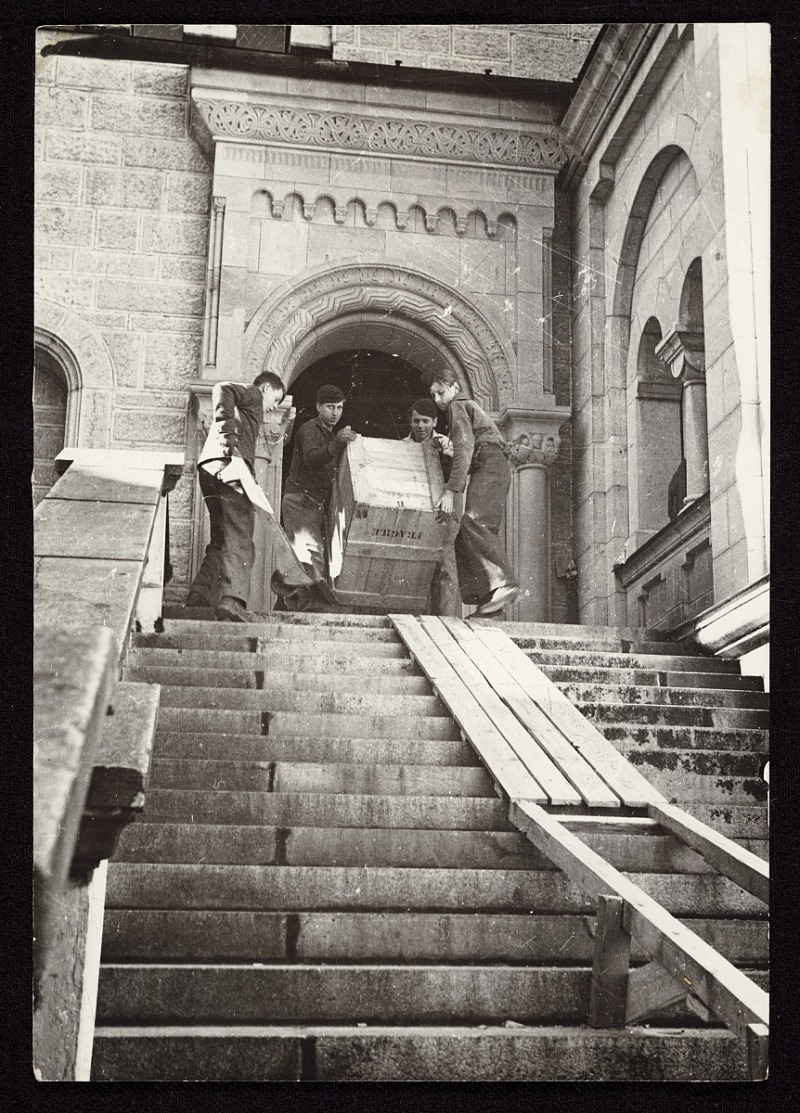

Rorimer and Skilton arrived at Buxheim to find American soldiers on guard at the side of the building. Local people, Germans desperately seeking dry goods that had been appropriated from France, had vandalized the room. Nothing in the one crate that they had pried open, though, had had an immediate use to the locals. They ignored or bypassed objects of extraordinary value that the American connoisseurs recognized immediately.

As Rorimer and Skilton entered the room, they saw rows of packing cases, seventy-two in all, stamped “Fragile.” The cases were crammed with beautiful paintings, including works by Watteau, Boucher, David, and Goya. On top of the vandalized crate were several pieces of bronze. Skilton picked up a gilt-bronze plaquette of Marie Antoinette. He turned it over and let out a tremendous yell when he saw that it had been marked in red with the official collection number of its former owner; just below, marked in black, he saw the letters “ERR” followed by a series of numbers.

The French shipping labels, which were still intact on the cases, told the story. They had been stamped “D-W,” an abbreviation that signified that they had belonged to M. David David-Weill, the eminent American-born, Parisian investment banker and art collector. When the Germans sacked Paris, he had been the Chairman of Lazard Frères and President of the National Museums of France.

For all the power and prestige these positions carried, David-Weill could not keep the art collection that he had chosen so scrupulously over decades from falling into Nazi hands. The black marking “ERR” on the cases confirmed what had happened to David-Weill’s art treasures: they had been acquired by peaceful means or even in an emergency sale dictated by the exigencies of war. A special unit of the Wehrmacht, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, had confiscated the collection.

This task force for cultural plunder was spearheaded by Nazi propaganda chief Alfred Rosenberg, who preached Aryan domination and practiced massive theft. From 1940 to 1944, fueled by racial fury and endless greed, ERR systematically stripped Jews of any and all prized cultural assets — fine and applied art, manuscripts, musical instruments, and sacred objects. Their aim, Skilton later wrote, was to “make Germany the greatest cultural center of Europe; in fact, of the world.” Unlike ordinary thieves, the ERR carefully numbered and cataloged every collection and object that they branded with their own stamp.

Buxheim was not Corporal Skilton’s first encounter with Nazi-stolen art. Not long after his arrival in Germany, he had been ordered to go to a unit near the front to examine eight paintings that had been found in a baggage car and bring them back to Seventh Army Headquarters if they were of sufficient value. One look had confirmed the aesthetic value of the recovered works, the most important of which was Tintoretto’s Holy Family. Skilton recognized that they had belonged to Jacques Goudstikker, the Dutch-Jewish art dealer whose entire collection had been looted after the Nazis overran Holland. Reichsmarschall Göring, who was particularly fond of getting his hands on art that he did not have to pay for, had plucked what he wanted for his own collection and sent the rest off to auction, the profits from which evidently went into his personal coffers.

Rescuing these old master paintings had been a challenge. None of the equipment that Skilton had at his disposal was remotely fit for transporting the works — always a delicate business — on the journey back to headquarters. He made do by wrapping them individually in blankets, which he put into the command car. Despite his precautions, his driver got lost deep in enemy territory as he struggled to find a bridge to cross the Rhine. “The driver was none too pleased,” Skilton recalled, “when I said that it really did not matter much what might happen to us, but that we must get the pictures to safety.”

Buxheim represented a different challenge. Corporal Skilton remained in the side room of the monastery to count and inspect the cases’ contents, while Lieutenant Rorimer directed his attention to the other parts of the monastery, which American military personnel had yet to enter.

He went round to the main doors, which were located in a courtyard behind a closed gate. He rang the bell and waited for a long while until the monastery’s resident director appeared and, later, returned with the repository’s superintendent. The two old Germans were neither openly hostile nor readily forthcoming. Finally, they grudgingly handed over the keys he needed to carry out his inspection.

Rorimer’s reconnaissance suggested that the ERR had converted the monastery into a repository for despoiled art. What he had not expected to find was that Buxheim also had become the ERR’s main center for art restoration. This is why he had encountered so many damaged objects as he conducted his inventory.

Lying perilously on one of the small tables that Lieutenant Rorimer spotted in the workshop was a small painting whose restoration was still in progress. He thought it was especially fine. He was right: the canvas was a Rembrandt. Its authorship was as clear as its provenance was murky. There was no record of who had owned the painting, but it evidently had come from a bank vault in Munich and been transported to Buxheim.

Buxheim’s restoration room astonished Rorimer. Nothing in his experience as a curator had prepared him for what he discovered within the monastery’s ancient walls. “There were few museums in the world that could boast a collection such as the one we found there,” he later wrote. “Works of art,” he continued, “could no longer be thought of in ordinary terms — a roomful, a car-load, a castle-full, were the quantities we had to reckon with.”

Even a partial list of the 158 paintings he had found at Buxheim underlined the aesthetic importance of the works of art the ERR had plundered. They included six Bouchers, four Watteaus (including the School of Watteau), seven Fragonards, one Vlaminck, two Delacroix, two Goyas, four Davids, two Reynoldses, two Gainsboroughs, one Greuze, one Guardi, and two Renoirs.

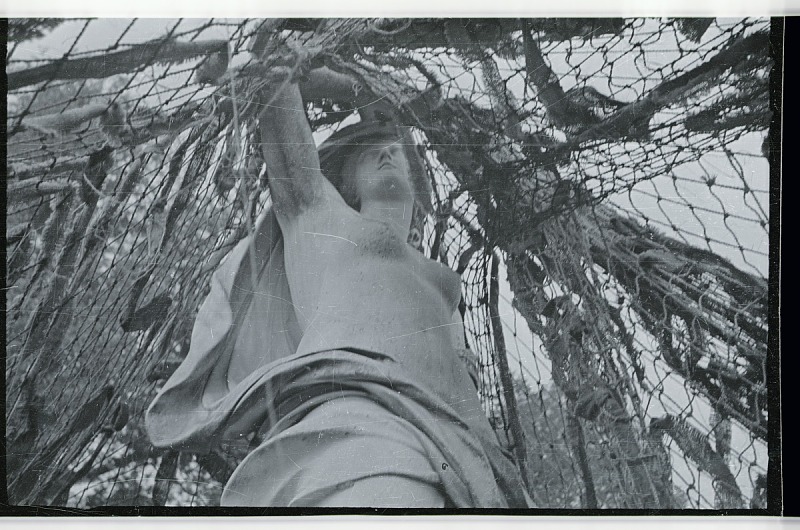

What they discovered in the famous Bavarian castle of Neuschwanstein, the neo-Gothic phantasmagoria conceived by “Mad King” Ludwig II who ruled Bavaria from 1864 to 1886 testified to both the range and quality of the works of art that certain Jewish collectors had acquired and to the depth and extent of Nazi art plunder.

Crucial issues remained unanswered, however. Neither Lieutenant Rorimer nor Corporal Skilton had the opportunity to discuss, let alone the authority to resolve, the complex questions of restitution. Deciding what should happen to the despoiled art they had recovered — how, when, where, and to whom it should be returned — would have to wait for another day, if not another time.

Since the late 1990s — more than five decades since these crimes were perpetrated — there has been a dramatic resurgence of interest in the fate of Nazi-stolen art. We are now well aware that Nazis and collaborators plundered thousands of works of art (as well as rare books and musical instruments) from Jews. We know that the legendarily upright Swiss furnished Hitler with both an Alpine money laundry and a clearinghouse for plundered art.

During and after the Nazi era, ignorant or unscrupulous individuals, institutions, and governments acquired despoiled works of art. It evidently was difficult for dealers, collectors, museums, and European states to resist the sudden availability of a bonanza of old and modern masterpieces. If some knew or suspected that gaps in wartime provenance signaled that they might be buying looted objects, others had little or no idea that there was anything wrong with their purchases.

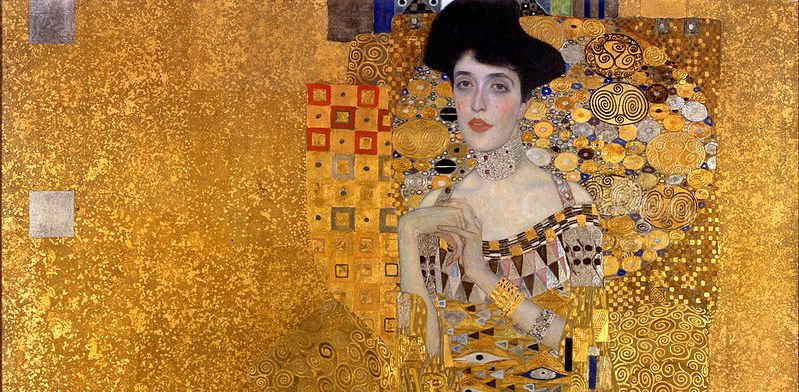

The fate of pillaged Nazi art has become a cause célèbre — a problem to be solved as well as a story to be told. The realization that countless paintings, drawings, sculptures, and objets d’art were never returned to their owners or their heirs provoked justified outrage. Rarely did months go by at the turn of the twenty-first century without articles in the press about the discovery of plundered art and bitter disputes about ownership. It seemed that no more major revelations would take place. Then, in February 2012, German authorities seized more than 1,400 objects valued at approximately $1.4 billion, including works by Matisse, Picasso, and Chagall that had been confiscated by the Nazis from the Munich apartment of eighty-year-old Cornelius Gurlitt. His father, Hildebrand Gurlitt, had been ousted by the Nazis from his position as a museum director because they considered him “one quarter Jewish,” but they had authorized him to buy and sell “degenerate” — which is to say, “modern” — art. long-delayed restitution of Nazi-stolen art, most famously the return of Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907) to its rightful heirs.

Even so, the danger of dwelling on the darkly enthralling story of theft and murder — how Nazis stole the art collections of Jews, along with many of their lives — is that it can obscure a compelling historical question: How did certain European Jews acquire so much great art in the first place, and what does this reveal about the Jewish encounter with modernity?

This book sets the protagonists’ stories against the backdrop of the broader changes that affected their fortunes and transformed art and society. Among them were the gradual opening of high culture; the dynamics of assimilation, acculturation, and antisemitism; the decline of the landed classes and ascent of a new capitalist elite; the cultural impact of the “Great War”; and the Nazi war against the Jews.

This is the untold story of Nazi-stolen art.