The recent discovery of the hull of the battleship Nevada recalls her dramatic action at Pearl Harbor and ultimate revenge on D-Day as the first ship to fire on the Nazis.

-

June 2021

Volume66Issue4

Editor's Note: Don't miss the first half of this essay, Two Hours in Hell at Pearl Harbor. Author Ed Offley, after serving in the Navy during Vietnam, reported on Naval issues for three decades for The Ledger-Star in Norfolk and The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. He was also Editor-in-Chief of DefenseWatch Magazine. Mr. Offley has written five books, including a favorite of ours, Scorpion Down: Sunk by the Soviets, Buried by the Pentagon. This is the second of a two-part essay on the dramatic history of the battleship USS Nevada (BB-36), which survived the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and went on to serve in the Aleutians, Atlantic convoy escort duty, the Allied liberation of Normandy and southern France, and the climactic battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

The mammoth warship steamed in darkness toward a new baptism of fire, its crew at General Quarters.

It was the early morning of D-Day, June 6, 1944. The aging battleship USS Nevada was heading for the coast of France to provide gunfire support for two of the American landing beaches at Normandy. In several hours, the U.S. Army’s 4th Infantry Division would go ashore at Utah Beach, aiming to link up with paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Division already dropped behind the German lines. Designated targets for Nevada and her two accompanying cruisers included 110 German artillery pieces spread throughout the inland area, as well as a twelve-foot concrete seawall. Their destruction was vital if the American soldiers were to survive and move inland.

Read the first part of this essay, Two Hours in Hell at Pearl Harbor, by Ed Offley

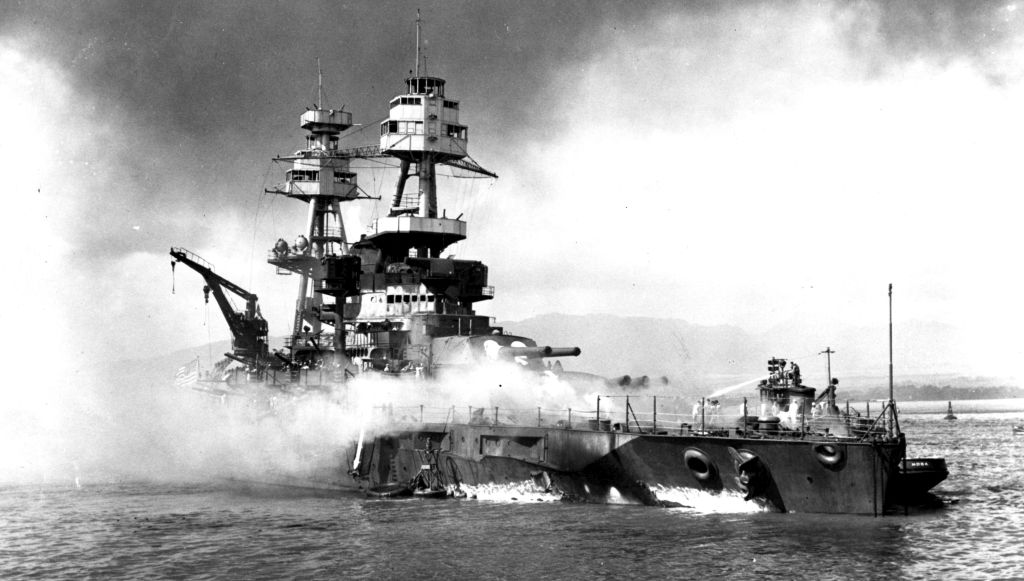

Few in the U.S. Navy would have imagined this scene thirty months before. During the deadly attack on Pearl Harbor, the Nevada was the only battleship able to get under way. She had been a dramatic sight as she steamed out from the smoke and flames. But then Japanese planes focused their deadly attack on Nevada, and she was soon broken and sinking near the harbor entrance.

Now the battleship was primed for combat halfway around the globe from where it had rested on December 7, 1941. She had already seen action against the Japanese in the Aleutians, but the test that her captain and crew now faced was far more deadly.

THE INITIAL assessment of damage to the Nevada after Pearl Harbor had been somber: Salvage crews and Navy divers inspecting the beached ship at Wapio Point in the days after confirmed that its hull was breached in two locations on the port bow where a torpedo had struck, and where a bomb from the second attack wave had caused a second immense hole. The entire forward part of the ship below decks had been gutted by fire, and the superstructure was likewise a shattered, burnt-out ruin.

All but 300 of Nevada’s crew were hastily reassigned to other ships as a salvage team began a herculean effort to patch up the hull and get the battleship refloated.

Working around the clock, shipwrights at Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard constructed massive patches to close the gaping holes in her hull. Eight weeks after the attack Nevada rose off the harbor seabed. Towed to Drydock 2, she received more rugged hull patches, replacement machinery and equipment during a sixty-five-day refit.

On April 22, 1942, a skeleton crew got the ship underway for Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Washington state, where Nevada underwent a major modernization that transformed her silhouette and significantly increased her combat power. The two tripod masts – long a defining feature on American battleships – were removed, replaced by a single foremast. A large SK-2 air-defense radar atop the new mast replaced the previous manned fire control stations.

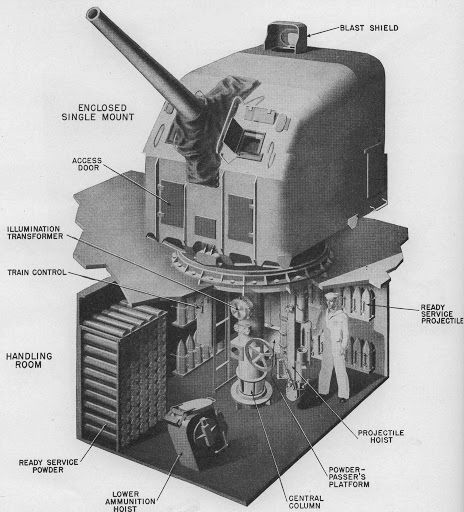

That new technology was part of a major upgrade to the ship’s anti-aircraft capability: Its old 5”/25-cal. AA guns and 5”/51-cal. secondary guns were removed and replaced by sixteen powerful 5”/38-cal. guns mounted in twin turrets, eight to a side. Eight quad-barrel 40-mm Bofors anti-aircraft guns and forty 20-mm. Oerlikon automatic cannons further increased the ship’s formidable defenses against air attack.

Since each of the 5”/38-cal. guns took about fifteen sailors to operate, and each gun had four complete teams standing rotating watches, the new secondary battery and Bofors/Oerlikon stations added more than 800 additional sailors to the crew, raising it from 1400 to over 2220 officers and men.

The Nevada’s original mission had been to fight as part of a fleet of battleships against an enemy force comprised of the same massive gunnery ships. Two factors transformed the ship’s combat role: the advent of carrier air power as the U.S. Navy’s predominant striking arm, and a radically different geostrategic situation.

The Navy now employed aircraft carriers capable of 30 knots at maximum speed in the leading role in offensive task forces. Battleships and cruisers would provide the flattops with air defense. But because the Nevada and the other older ships could only make 21 knots, they could not keep up. The air defense role would go to three classes of newer “fast battleships” that joined the fleet during 1941-44, which were also capable of 30 knots.

With the entry of the United States into the war against the Axis powers of Germany, Italy and Japan, the U.S. Navy now found itself forced to plan for a prolonged “island hopping” campaign in the Pacific to roll back the Japanese, and a series of landings in Europe to take the fight to the Germans and Italians. The role of the older battleships would now focus on gunfire support during these amphibious assaults.

The Nevada, in fact, would go down in U.S. naval history as the only battleship to fight in six major campaigns across the globe: the recapture of the Aleutians, Atlantic convoy escort duty, the D-Day invasion of Normandy, the subsequent Allied landings in southern France, the seizure of Iwo Jima, and the invasion of Okinawa.

When Nevada left Long Beach, California, on its first wartime mission on April 7, 1943, all but a handful of Pearl Harbor survivors in its 1400-man crew had joined the battleship since the major overhaul and modernization at Bremerton. But the crew had worked hard on their gunnery skills off Southern California for several months, and girded themselves for their first wartime mission. On May 11, Nevada two other battleships and twenty-seven destroyers escorted five troopships carrying over 10,000 soldiers from the 7th Infantry Division to Attu island in the far western Aleutians.

The Japanese had occupied Attu with over 2000 soldiers in June 1942, ostensibly to block any American military campaign against the home islands using that ersatz land route. Both the Japanese invasion and the American recapture mission were plagued by the island’s mountainous topography, frozen tundra and near-permanent gale-force winds and heavy clouds.

Nevertheless, Nevada during a three-day period fired nearly 250 rounds from its main battery and another 46 from the 5”/38-cal. secondary, giving its untested crew some valuable experience under wartime conditions.

Returning to the “lower 48” in June, Nevada briefly underwent a maintenance and repair period, then served as a convoy escort task force leader for several trans-Atlantic crossings. This phase of her wartime service was uneventful, coming right after the German U-boat force abandoned the North Atlantic in late May following several massive defeats at the hands of the Allies’ convoy escort groups. But orders for a major wartime mission were not long in coming.

Arriving in the waters of Belfast Bay, Ireland, on April 27, 1944, Nevada and the other warships of the Western Naval Task Force conducted “intensive training in gunnery, bombardment procedure, communications and damage control” in advance of the D-Day landings.

The task force steamed south for the English Channel and in a carefully coordinated naval maneuver involving nearly 5,000 warships, troop transports and landing craft, closed in on its target zone at Utah Beach in the pre-dawn hours of June 6, 1944.

Firing from a position just four nautical miles offshore, Nevada and the other warships targeted German gun emplacements and troop formations inland to support the paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division who had landed several hours earlier; blasted holes on a massive German concrete seawall installed to thwart an amphibious landing. Airborne spotters provided the battleship gunners detailed firing instructions that made pinpoint accuracy possible against targets up to fifteen miles inland.

“At Normandy, we were at General Quarters for eighty hours nonstop,” said Richard Ramsey, then a 20-year-old gunner’s mate assigned to one of the 5”/38-cal. gun crews. “We had the honor of firing the first round at the Germans.”

On D-Day alone, Nevada fired 377 massive 1,500 lb shells from the 14”/45-cal. main battery guns and 2,693 rounds of five-inch ammunition. The heavy guns were capable of firing over thirty miles, and on June 6, Nevada succeeded in breaking up a German tank formation attempting to break through a vital 101st Airborne position.

The following day, Nevada’s gunners helped destroy several German artillery emplacements that were threatening the Allied beachhead, and broke up an enemy troop formation trying to close in on the paratroopers. On June 8, the battleship gunners were alerted to a major German armored column comprising 90 tanks and several dozen trucks near the main road to Cherbourg. The big guns destroyed the formation.

After returning to Plymouth for provisions and ammunition, the battleship returned to Normandy waters on June 15, with orders to bombard the German-held port of Cherbourg. This time, the Germans fired back with 11.2-inch shore batteries. Nearby battleship USS Texas took one German shell on her superstructure, but Nevada – though straddled thirty-two times – avoided any enemy damage during a gunfight where she fired another 1216 of her main battery and 3531 five-inch shells.

Once more returning the England for resupply, the battleship joined another naval task force, which passed through the Strait of Gibraltar and entered the Mediterranean on July 4. The assignment would be identical to Utah Beach: provide gunfire support for the planned Allied invasion of southern France in Operation Anvil at Marseilles and Toulon.

After three days shelling targets near Marseilles starting on August 15, Nevada was ordered to Toulon, where she engaged in a long-range artillery duel with the captured French battleship Strasbourg anchored in the harbor. The American naval gunners scored at least one direct hit on the enemy warship, and helped pulverize the fortified gun emplacements around the harbor. The Nevada continued bombarding German gun positions until August 24, when on its final day in the operation, the ship blasted six German gun batteries on several islands near Marseilles.

While heading back through the Strait of Gibraltar for the United States and a maintenance overhaul at New York Naval Shipyard, Nevada’s crew received a heartfelt message from its executive officer, Commander Howard A. Yeager: “Through the long days … you performed your duties in a seamanlike manner and proved conclusively that the ship that the [Japanese] had counted out at Pearl Harbor was far from finished. … After our baptism of fire at Normandy, we were a battle-hardened organization and ready for anything. At Cherbourg we received the acid test. … The Nevada’s participation in the invasion of southern France … again reflects the fighting organization of this fine ship.”

Yeager added, “You are about to go home on leave – have a good time – enjoy yourselves. Be proud of your uniform and your ship – you have a well-earned right to be.”

Their respite would be brief. Even before leaving the European theater, the Nevada received new orders. The Pacific War was still raging, and their gunnery would be needed in two battles that would prove even more challenging than the firefights along the coast of occupied France.

THE NEVADA GLIDED through the darkness, heading for yet another pre-dawn rendezvous with a hardened enemy. Its exterior lights extinguished, its decks and superstructure seemingly abandoned, only the faint murmuring of the boilers and steam turbines at work deep inside the hull, and the quiet rasp of exhaust fumes rising from its slanted stack, gave any sign of life. Nearly three-fourths of the battleship’s 2220-man crew lay asleep in their bunks below decks. The outward calm was deceptive: about 500 of the ship’s officers and enlisted men were standing the 0400-0800 watch – fighting fatigue and tension with black coffee and an occasional quick break on deck.

The Nevada was surrounded by dozens of other warships steaming in formation on a southeasterly course. Ahead, the first hint of morning twilight showed a faint brightness on the horizon. The destination of three separate U.S. Navy task forces totaling more than 800 warships, support vessels and large landing craft still lay hidden below the curve of the earth. A total of 220,000 American sailors and 100,000 marines were converging on the small Pacific volcanic rock the Japanese called Sulphur Island – in Japanese kangi: Iwo Jima.

It was nearly five months since Nevada had arrived at New York Naval Shipyard for a two-month overhaul and long-overdue R&R for her crew. When finished, the ship traveled south to the Caribbean, passed through the Panama Canal, and made the long trans-Pacific voyage to the vast American naval anchorage at Ulithi in the Caroline Islands. For two months, her crew conducted intense gunnery and communications drills for what would become the most intensive naval bombardment campaign to date in the war.

After three days of preliminary bombardment, the full invasion force arrived off Iwo Jima just prior to dawn on February 19, 1945. Task Force 54, the bombardment group, consisted of nine battleships, fourteen cruisers and several dozen destroyers. Because of the ship’s excellent record in the European theater, Nevada was selected as flagship for task force commander Rear Admiral Bertram J. Rodgers.

The bombardment plan for Iwo Jima was ambitious. In previous amphibious assaults, Navy and Marine Corps planners had become familiar with the Japanese tactic of placing their defenses deep underground, and carefully camouflaging gun emplacements. Pre-invasion reconnaissance of the four-and-two-third-mile island confirmed that Iwo Jima would prove the same case. Naval planners divided the island into more than seventy grids, and each warship had detailed topographical maps identifying its specific target area, including known caves, gun emplacements, pillboxes and other sites. Nevada’s grid comprised the landing beaches and immediate inland terrain on the southeastern coastline where the Fifth Marine Division was to come ashore.

At 0555 hours, the pre-dawn quiet abruptly ended. The 1MC loudspeaker sounded again with a loud blare of the ship’s klaxon, “This is not a drill! This is not a drill! All hands man your battle stations! General Quarters! General Quarters! Set Material Condition Zebra throughout the ship! General Quarters!”

Throughout the Nevada, the decks trembled as 2000 crewmen pounded to their battle stations. On the fantail, crewmen readied the thirty-foot hydraulic catapult that would launch the ship’s two OS2U Kingfisher spotter planes. Once aloft, each aircraft’s two-man crew would orbit above the target area, calling in adjustments to the ship’s gunfire.

The battleship was now in position under four miles offshore – point-blank range for her ten 14”/45-cal. main guns. Lookouts atop the superstructure peered through binoculars at the grey, featureless terrain, broken only by the towering slopes of Mount Suribachi off the port quarter at the island’s southern tip. Nevada’s four main gun turrets and port-side secondary mounts trained out to port until they were just a trigger pull away from blasting the Japanese defenses on the Fifth Marine Division beaches.

At 0654 hours, commanding officer Captain Homer L. Grosskopf seized the 1MC microphone. His voice echoed throughout Nevada’s compartments, passageways, and gun turrets: “Now commence transferring ammunition to Iwo Jima! Good luck, and commence firing!” Both the battleship and island disappeared behind walls of smoke and flame as the invasion of Iwo Jima began.

In three days of pre-invasion bombardment and prolonged gunfire prior to the actual landings, the Nevada had fired 870 of her 14-inch shells and 4,689 five-inch shells at assigned targets on Iwo Jima. As the Marines ashore would learn to their grief, much of the Japanese defenses survived the barrage simply because they were dug in so deeply.

After sunset on D-Day at Iwo Jima, the Nevada came to the rescue of the 28th Marine Regiment when a Japanese battalion counterattacked. In a moment of improvisation, Captain Grosskopf ordered his gunners to fire a blanket of starshells above Iwo Jima, which brightly illuminated the zone and helped the Marines thwart the attack. By the fourth day of the operation, enough Marine artillery units were ashore that they assumed the primary gunnery role against the Japanese.

By D-Day plus 10 on March 1, the bombardment force had been reduced from twenty-two battleships and cruisers to twelve, including Nevada. Apart from three fire missions on March 1, 6 and 7, the battleship – like the rest of the gunfire task force – remained on station in case of a major battlefield flareup or attack by the now-depleted Japanese navy. Its only casualties were the two-man crew of one of its spotter planes, killed when their Kingfisher was shot down by Japanese gunfire. But as the battleship departed on March 8 for the return trip to Ulithi anchorage for fuel, supplies and ammunition, the atmosphere on the ship remained tense. The crew had just three weeks to prepare for a larger, more prolonged, and far more dangerous mission: the invasion of Okinawa.

OPERATION ICEBERG was the largest amphibious operation in World War II, and the most ferocious battle for the Marines and soldiers in the entire Pacific campaign. More than 500,000 American and allied servicemen aboard a naval force exceeding 1,500 ships took the fight to the last fortified island standing in the way of the Japanese home islands. This included three Marine divisions and four Army divisions.

More than 100,000 Japanese soldiers were dug in deep underground awaiting them. Offshore, Nevada was still part of Task Force 54, the bombardment force, now comprising ten battleships, ten cruisers and several dozen destroyers providing naval gunfire and air defense support to the landings. Over the span of a hellish twelve-week ground campaign, the Marines and soldiers would lose over 7163 killed and nearly 32,000 wounded, while over 107,000 Japanese and Okinawan military personnel and civilians died.

Unlike Iwo Jima, the Navy would also experience major casualties, primarily at the hand of kamikaze planes that had already drawn blood during the recapture of the Philippines four months earlier. With the military situation becoming untenable, Japan unleased massive suicide attacks by kamikaze aircraft that would ultimately sink 20 warships and auxiliaries. This included ten separate mass attacks by between 50 and 300 aircraft. At Okinawa, Nevada would have the dubious honor of being the first of five battleships to absorb a kamikaze strike.

The ship’s first combat fatalities since the Pearl Harbor attack occurred during a pre-invasion bombardment mission in the morning of March 27, five days before the actual landings were to begin. Aboard his flagship USS Tennessee, Task Force 54 commander Rear Admiral Morton L. Deyo watched the blow. The task force was heading toward its assigned gunfire location off the western beachfront facing the Kadena military airfield when seven Val dive bombers attacked the formation. Several planes were quickly shot down, but one Val got through and dove at the Nevada despite taking hits that set it afire.

“It staggers, pulls partly out, but then resumes the dive,” Deyo recalled years later. The dive bomber struck Nevada’s No. 3 turret aft, knocking out its three 14-inch guns, destroying three 20-mm. anti-aircraft gun mounts and wrecking the ship’s two Kingfisher spotter planes. The attack killed eleven crewmen and wounded another forty-nine. A second Val attacked at the same time but blew up from a direct hit from one of the ship’s five-inch guns. After the fight, all crewmen except for watchstanders attended a burial-at-sea service for their dead shipmates. The battleship remained fully operational, and for the next four days helped pound Japanese defense positions prior to the landings on April 1. During the twelve weeks that followed, as the American ground forces fought cave by cave to overcome their determined foes, Nevada’s crew stood at battle stations around the clock providing gunfire support while confronting the kamikaze threat.

A second – but far less serious – blow occurred on April 5, when a hidden gun emplacement ashore struck Nevada with five six-inch shells, killing two crewmen and wounding seventeen. In return, Nevada obliterated the Japanese gunners with a salvo of seventy-one 14-inch shells. For Gunner’s Mate 3rd Class Dick Ramsey, the incident was especially poignant: Just a few minutes after he rushed from his berthing compartment when General Quarters sounded, the fatal six-inch shell that struck the ship passed through several decks before blowing directly through his bunk. Ramsey vowed to shipmates he would be even faster to his GQ station the next time.

When the Okinawa campaign was finally declared over on June 22, Nevada and other battleships returned to sea for patrols in the East China Sea. The ship was provisioning at Leyte in the Philippines when the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima. It would take several weeks before word officially reached the crew that their long war was finally over at last.

ITS FINAL mission would confirm the battleship’s nickname, “Invincible Nevada.” It was a task that only a handful of her proud crew would get to witness.

The signing of the formal surrender by Japan on September 2, 1945 did more than bring an end to hostilities between the two nations. It also closed out the careers of the workhorse battleships that had formed the backbone of the Navy before Pearl Harbor. In a press conference shortly after V-J Day, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz was succinct: “Battleships are the ships of yesterday, aircraft carriers are the ships of today, but submarines are going to be the ships of tomorrow.”

Of the twenty-three battleships that saw combat after Pearl Harbor, all but the four newest Iowa-class ships effectively saw their service end with the Japanese surrender. Between 1946 and 1965, most were mothballed, then either sold for scrap or handed over to namesake states as museum ships. Nevada was one of four that went out with a bang.

In 1946, the Navy assembled a large fleet of inactive warships at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands for the first in a series of atomic bomb tests in Operation Crossroads. For the nascent Air Force, the exercise was to test the effectiveness of nuclear weapons against an enemy fleet; for the Navy, the operation was to determine that modern warships could survive a nuclear attack. Future defense missions, operational priorities and funding were all at stake.

Despite her valiant service, Nevada had been deemed obsolete for the postwar era, and was one of four older battleships assigned to this “ghost fleet” of 95 warships, auxiliaries and landing craft. Planners chose her to be ground zero, so after four years of wearing various camouflage paint schemes, she sailed off with a diminished crew of 1,200 men on her final deployment, sporting a bright orange coat of paint.

Shot “Able,” the first test, was the air drop of a 23-kiloton plutonium-core atomic bomb from a B-29 flying at 30,000 feet. The general expectation was that the blast would sink the Nevada and four other ships anchored nearby. Witnesses on ships ten miles away saw the signature ball of fire erupt when the bomb went off at an altitude of 500 feet. A giant mushroom cloud soared 40,000 feet into the air. But when the cloud dissipated and the water calmed, Nevada was still afloat. Embarrassed Air Force officials learned the aircrew had missed their orange target by some 700 yards.

Three weeks later, shot “Bravo” went off. This time, the atomic bomb was suspended beneath a landing craft and detonated 90 feet underwater. In addition to damage from the supersonic shock wave of compressed seawater, the “ghost fleet” was saturated with high levels of radiation. The battleship USS Arkansas (BB-33) was the closest ship to the bomb. It was crushed, capsized and sank. One witness later recalled shouting, “This is incredible! You can see light under the entire length” of the Nevada. “She is actually up in the air!” Once again, the battleship declined to sink.

However, scientists after the blast found that Nevada was too dangerously radioactive to safely board. The battleship was left at anchor in Bikini Atoll for three months before being towed to a pier at Kwajelein. Formally decommissioned on August 29, 1946, the ship remained tied up at the pier for another two years before the Navy finally decided to sink her as a target.

In late July 1948, a task force of fourteen Navy warships – including a battleship, three cruisers and a destroyer squadron, supported by sixty naval aircraft – converged on the empty and still-radioactive Nevada where the ship slowly drifted in the open ocean some sixty-five miles southwest of Oahu. The pilots and naval gunners thought they would make quick work of the old warship. They were wrong.

The Navy first set off a large explosive device installed on board. This opened up several holes in her side and buckled the main deck, but Nevada showed no sign of sinking. The ships and aircraft then proceeded to testing a variety of new weapons on the old battleship. Aircraft struck her with several experimental radar-guided missiles. Alas, all missed.

Next, the task force commander ordered several destroyers to rake the ship with 5”/38-cal. gunfire. The battle rolled and pitched as she absorbed several dozen hits. When the dense cloud from the exploding ordnance cleared, it was clear from her battered superstructure that Nevada was in poor shape, but – once again – she refused to sink. Exasperated, the task force commander next ordered a swarm of aircraft to fire a swarm of aerial rockets.

The barrage knocked one fire control director off its mount; several more shredded the ship’s tall stack, while yet another penetrated the hull and exploded. The aircraft flew back to Pearl Harbor. The Nevada stubbornly refused to go down.

Frustrated and embarrassed, the task force commander then summoned the USS Iowa. The fast battleship fired salvo after salvo of her 16”/45-cal. main guns at the drifting orange target. The ship vanished in yet another cloud as several dozen 2000-pound armor-piercing rounds struck and detonated. Same result.

He then ordered the cruisers USS Astoria, USS Pasadena and USS Springfield to execute a massive fire mission. From a distance of twelve miles, then at point-blank range just five miles away, the three warships pummeled Nevada with a blizzard of armor-piercing shells from Astoria’s 8”/55-cal. main batters and the lighter, 6”/47-cal. guns of the two light cruisers. This sixth attempt to sink the battleship was no more successful than the others.

Having failed over a six-day period to send Nevada to her assigned grave on the Pacific seabed, the task force commander on July 31 summoned a Navy torpedo bomber, which struck Nevada amidships and opened up a hole similar to the one inflicted by the Japanese Kate at Pearl Harbor six and one-half years earlier. Thirty minutes later, the old battleship took a list to starboard and suddenly capsized and sank.

When news of the sinking appeared in newspapers across America, many of Nevada’s former crew wept.