Because of wartime gas-rationing, Congress and the administration debated cancelling the famous gridiron match-up between Army and Navy in 1942. President Roosevelt found a novel solution.

-

Spring 2018

Volume63Issue1

In the weeks after Pearl Harbor, the Japanese conquered most of the areas of Southeast Asia that produced rubber and cut off supply to the U.S. By the following year, the situation became so dire that the government formed 7500 tire ration boards each staffed by three volunteers to manage the allocation of scarce tires around the country.

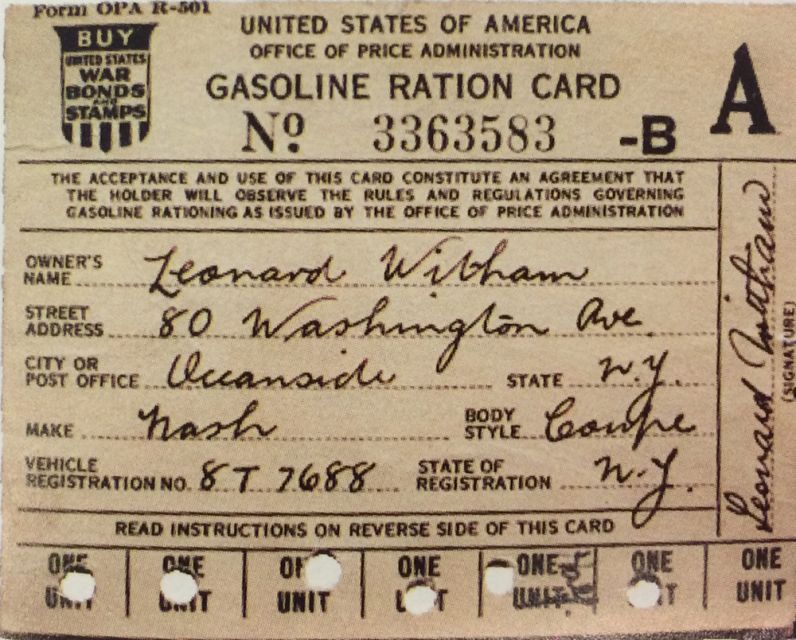

To help conserve gasoline and especially rubber tires, the government ordered gas rationing in 17 eastern states beginning in May and then nationally in December, and a speed limit of 35 miles per hour enforced nationwide. Drivers who used their cars for work essential to the war effort received additional gas ration stamps.

What should be done about the Army-Navy game, traditionally played in the “neutral ground” of Philadelphia, since neither West Point cadets nor Navy midshipmen could travel to the game?

Congress and the Cabinet debated cancelling the time-honored match. At the time, my father, Navy Commander Bill Mott, worked in the White House Map Room and often brought messages to President Roosevelt. Both men were avid fans of Navy football and discussed it on many occasions. Later, Naval Academy coach John “Billick” Whelchel and assistant coach Edgar “Rip” Miller generously credited Commander Mott with nudging the President’s decision, but he always insisted their gratitude was undeserved since Roosevelt had already made up his mind to order the game to be played. The Army-Navy face-off was key to morale at both academies, he declared, and good for the country, too.

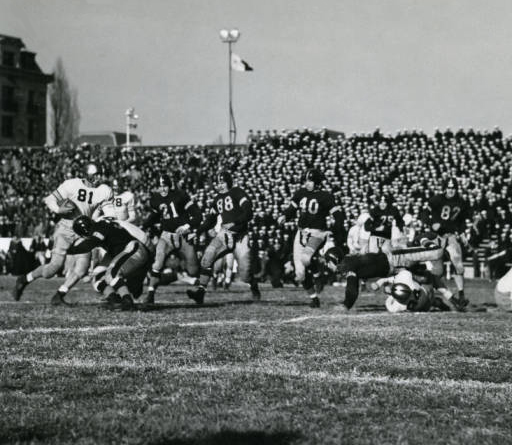

The game was relocated from Philadelphia to Thompson Stadium at Annapolis, but wartime travel restrictions would limit attendance to mostly local spectators. Since West Point’s Corps of Cadets, Army’s traditional cheering section, was not allowed to make the trip, another novel accommodation was made. The Naval Academy’s third- and fourth-year midshipmen were ordered to sit behind the Army bench and cheer for the visiting team. The 1942 match grew more unusual by the hour.

Newsmen in attendance wrote enthusiastically about Army’s Navy-populated cheering section. Midshipmen braying the Corps cheer was living proof of inter-service comity, they reported. Even the touchdown-starved Army players expressed gratitude to the cheerleaders, despite their 14-0 loss in a match they had been heavily favored to win. The 1942 game would be Navy’s fourth consecutive victory over West Point.

Game attendance may have been a tenth the size of the usual hundred thousand sellout in Philadelphia, but President Roosevelt had correctly gauged the national interest in the match. An unprecedented forty million Americans tuned in to the live radio broadcast. The defiant, patriotic fervor at Thompson Stadium compensated for the reduced spectator size. From the emotional opening remarks to the extra staccato in the last stanza of the Annapolis school song, “Navy Blue and Gold,” fans wept, cheered, and sang themselves hoarse on their country’s behalf.

Coach Rip Miller wrote my father after the game, thanking him for his “splendid work in keeping the navy football team before ‘the big head coach.’ I don’t know where we could do any better for our cause here than what you have made possible for us.”

Commander Mott continued to refuse credit, but was so pleased by the overall turn of events that he started advancing the idea of sending game reels to Admiral Halsey’s men in the Pacific. As it happened, the garrulous Admiral William “Windy” Calhoun, commander of the Service Force of the Pacific Fleet, was in town to meet with officials from the White House, State Department, and War Department in the days following the game. My father was assigned as his escort.

During their banter to and from the meetings, Bill mentioned that had seen the army-navy game films and casually suggested sending them out to the Pacific. Calhoun’s eyes widened. “Terrific idea, Commander! Great for morale!” He clapped Bill on the shoulder and asked for copies of the reels to take back to Pearl Harbor with him. Bill savored the fact of having a hand in dispatching the films to the war front, particularly given Navy’s shutout victory.