Col. Harry Stewart downed three advanced Nazi fighter planes in one day, then surprised the Air Force when he and his Tuskegee teammates won the first "top gun" competition.

-

Summer 2023

Volume68Issue4

Editor’s Note: A longtime pilot and aviation historian, Philip Handleman is co-author with Lt. Col. Harry T. Stewart, Jr. of Soaring to Glory: A Tuskegee Airman’s Firsthand Account of World War II, from which he adapted portions of this article.

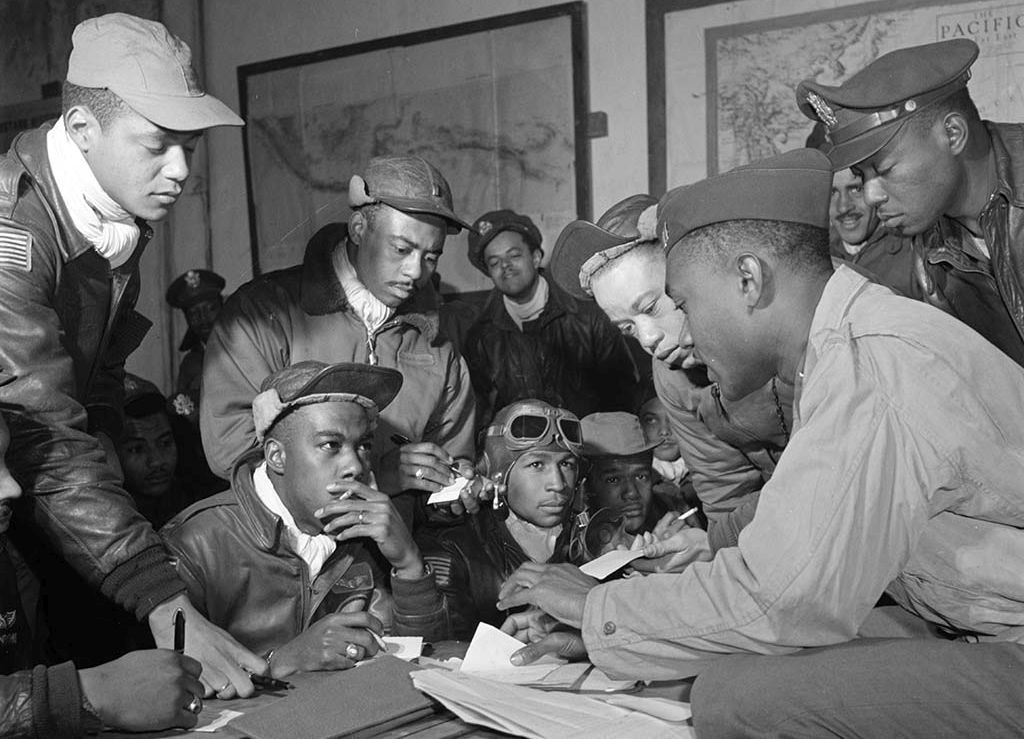

Lt. Harry Stewart was flying five thousand feet over the Luftwaffe base at Wels, Austria with six other Tuskegee airmen in their distinctive red-tailed P-51 Mustangs when someone in his squadron yelled that there were four German fighters below. The Americans should have been more than a match for them.

“Our seven Mustangs cranked over in a mass dive on the enemy aircraft,” Harry recalls. But, suddenly, the hunters turned into the hunted as “the sky filled with at least another dozen fighters bearing Luftwaffe insignia.”

The enemy planes they initially spotted were decoys. The Americans had been lured into an ambush. The irony of the date was not lost on Harry. It was April 1, 1945 – April Fool’s Day.

The confrontation was certain to end with some of the planes zooming down from the sky in spectacular crashes. Harry began breathing heavily. Everything was happening so fast now.

Barely out of his teens and never before engaged in a dogfight, Harry was almost overwhelmed by the thoughts flashing through his mind. There was the anger at having been suckered into a trap. There was the terror of the high-stakes dueling about to transpire. Then, the instinct for survival kicked in. The young pilot’s fear and doubt, a sinking feeling in the pit of his stomach, gave way to a fierce determination, bolstered by his training.

Just days before, Harry had been promoted to first lieutenant. But matters of rank were the furthest thing from his mind as he locked eyes on the two enemy planes beneath him. He advanced toward his prospective quarry as individual skirmishes broke out among the other combatants.

As Harry bore down on the tails of the planes in front of him, he saw that they were the long-nosed Focke-Wulf Fw 190D-9s, known as the “Dora-Nines” and considered the finest piston-powered fighters in the Luftwaffe’s arsenal.

The Mustang’s speed brought Harry within firing range. He concentrated on the closer of the two German aircraft, then squeezed off a few short bursts from his six wing-mounted .50-caliber machine guns.

Smoke and flames suddenly sprouted from the Dora-Nine’s fuselage, imprinting a ghastly picture in Harry’s memory.

As events evolved in fractions of a second, Harry knew only to stay on the fighter’s tail. He contemplated another burst. But the plane in his gunsight had already started to break apart. An eagle’s wings had been clipped; the staff officers at Allied intelligence could scratch off one more Luftwaffe fighter.

But there was no time to relax and savor this victory. There was another enemy fighter dead ahead. When the second Luftwaffe pilot realized what had happened to his trailing wingman, he yanked his plane hard right in an attempt to shake Harry off his tail. But Harry turned just as tightly, pulling high Gs which stretched the Mustang to the limits and pressed him down in his seat.

The high-G maneuvering made Harry sweat like hell. In another fleeting second, he trained his sight on the tail of the bolting fighter and squeezed off a burst. An instant later – in a sight that would also be seared in Harry’s memory – the plane started to dissemble “in a cloud of black smoke and orange flame just like the first one.”

Harry had scored his second victory of the day. But, before he could even breathe a sigh of relief, he heard a squadron mate’s urgent call: “Bandit on your tail!” It was the voice of Carl Carey, another Red Tail who had scored against two of the Dora-Nines himself.

Just then, tracer rounds started to whiz past Harry’s cockpit. They were frightfully close. The sinking feeling in his stomach came back.

Harry used his fighter’s speed again, hoping to outrun his new opponent. But the pilot of the Focke-Wulf was tenacious. With the enemy glued to his tail in a sprint at treetop height, Harry made an extreme right turn. The German plane followed him, turning and turning in a test of strength and will, the G-forces almost unbearable.

Men and machines were ratcheted to the limits of their capacity. Something had to give. Then, in the next moment, Harry realized that he was free.

In the corner of his eye, he spotted the Focke-Wulf cartwheeling across the ground, curling up, and then exploding in a ball of fire. In the heat of the chase, somehow, the German fighter went from feared predator to smoldering cinders.

Afterwards, Harry and his fellow 301st Fighter Squadron pilots speculated that the enemy fighter had inadvertently stalled and snap-rolled in the high-stress maneuvering low to the ground. Perhaps the unlucky pilot became fixated on Harry’s Mustang and failed to pull up over the undulating terrain as the dogfighting planes skimmed fast and low. Or maybe the German fighter nicked a tree.

Another factor was the probable youth and lack of seasoning of the Luftwaffe pilot. By this late in the war – a few weeks before the Nazis’ surrender – the Germans had experienced horrendous attrition in their pilot ranks. Unlike the 332nd Fighter Group’s pilots, who generally flew 70 combat missions and then rotated home, the Germans operated on “You fly until you die.”

Harry was credited with three aerial victories for the day. He assiduously avoided asking for the third Focke-Wulf to be added to his score. With fellow pilot Carl Carey vouching for the downing (in the absence of gun-camera footage), Harry’s bosses chalked it up to his performance in the engagement.

Percy Sutton, the squadron’s intel officer debriefed Harry after the mission and recognized that what Harry had done would qualify for the Distinguished Flying Cross. Sutton put in the recommendation.

The public relations value of Harry’s three kills in a day was recognized by the higher-ups at group and command headquarters. The next day, he was posed in the cockpit of his P-51, nicknamed "Little Coquette," with three fingers raised, signifying his victories. Behind him, standing on the P-51’s wing, was his trusted crew chief, Jim Shipley.

Photos and press releases went out to the black press in hopes of favorable coverage in the pilot’s hometown and elsewhere. The New York Amsterdam News ran a laudatory article under the headline “Corona Flyer Shoots Down Three Planes.” The newspaper writer described the air battle as a “wild and vicious dogfight” and quoted Harry’s description of the action: “’It was a heck of a fight. It seemed as if Jerry was all over the sky that day … I guess I was just lucky.”

Harry Becomes One of the Red Tails

Harry T. Stewart, Jr. grew up in the Corona section of Queens, New York, and after school, he often hiked to nearby North Beach Municipal Airport to watch the airplanes take off and land. On October 15, 1939, the airport was rechristened LaGuardia Field in a celebration attended by 325,000 people.

On the day of the big event, fifteen-year-old Harry joined the crowd and was fascinated to see a silvery new Douglas DC-3 airliner, a pioneering design that was turning commercial air transport into a viable industry.

The next year, transoceanic service from New York began with majestic Boeing 314 Clippers. Harry loved to watch the long-range flying boats take to the air from LaGuardia’s new Marine Air Terminal, which connected the city to the faraway shores of Lisbon and Southampton.

Dreams of flight filled the teenager’s head. Flying these leviathans of the sky is what he wanted to do. But, when his history teacher and counselor, Grace McLaughlin, heard this career choice, she teared up. She didn’t have the heart to tell him that for a black kid in Depression-era America, a flying career, especially with an airline, was out of the question.

But the war was shaking things up, and Harry found a pathway to flying high-performance aircraft. He learned about the Tuskegee Airmen when he came across a magazine article in his school library on the first all-black fighter unit.

With America’s entry into the war, he bid his time until reaching enlistment age, and then promptly signed up for the blacks-only Army flying school in Alabama.

Harry’s train ride down South was an awakening for a young man who had seldom ventured beyond metropolitan New York. As soon as the train crossed the Mason-Dixon line, he was directed into a separate car for black passengers.

Such personal indignities were the price he paid in order to fly. Looking ahead, he understood that serving the country in uniform offered him the opportunity to achieve what the Pittsburgh Courier had described as the “Double V” – victory overseas in the war against totalitarianism and victory at home against racism.

Activated in early 1941 under pressure from civil rights advocates such as Walter White of the NAACP and A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the black flying program was one of the Roosevelt administration’s concessions to an important constituency.

Eleanor Roosevelt added her voice to the cause and famously showed support by going up for a ride in one of the training planes piloted by C. Alfred “Chief” Anderson, a record-setting black pilot and the Tuskegee Institute’s chief flight instructor.

By the time Harry arrived at Tuskegee in 1943, primary flight instruction was provided at Moton Field, and the classes were held on the Tuskegee Institute’s campus. Big-barreled AT-6 advanced trainer planes with their distinctive greenhouse canopies filled the sky above the Tuskegee Army Airfield where cadets received advanced flight training.”

For Harry, the atmosphere was intoxicating. The black cadets were preparing to defend the country and prove themselves as patriots and first-class combat pilots.

There was something more for Harry. His paternal grandfather had been born into slavery in Alabama during the Civil War. Accordingly, on each flight over the farmland of the heart of Dixie, he was acutely aware of his ancestors. In just a few generations, his family had traveled far. Soon, Harry would go even further.

His father, Harry Stewart, Sr., had grown up in Hampton, Virginia and escaped from Jim Crow oppression in 1925 when he hired on as a galley cook with an East Coast shipping company. The next year, on his first port call in New York harbor, he walked off the passenger liner and kept going, never looking back. Soon after arriving, he sent for his wife, Florence, and their children. The Stewarts made their home on the top floor of a five-story tenement in Harlem. After jobs as a doorman and garment-industry worker, Harry, Sr. got a job at the Brooklyn General Post Office, which gave him a steady income and job security. Around the time of the stock market crash, the family moved to the Corona section of Queens for more space and better schools.

In June 1944, the Army’s coveted silver wings were pinned on Harry, Jr.’s uniform, signifying his new status as a pilot and second lieutenant in the world’s leading air force. He was one of not quite a thousand black American men who would complete the training at Tuskegee. The wartime performance of the segregated program’s graduates would prove to be a major step in breaking the color barrier in the sky.

After additional training on frontline fighters at Walterboro, South Carolina, Harry was shipped overseas to join the combat. He arrived as a replacement pilot at Ramitelli, Italy in January 1945, joining the 302nd Fighter Squadron of the 332nd Fighter Group, known as the Red Tails for the bright red markings on the tail sections of their P-51 Mustangs.

The pilots of the 302nd took him under their wing. They mentored him as only grizzled combat flyers could, filling in the gaps in his stateside flight training so that, when his time came to face fighter pilots of the vaunted Luftwaffe, he would be ready.

As things turned out, Harry’s affiliation with the 302nd was short-lived. He was moved into the 301st squadron.

Years later, when asked during a conference who his heroes were, Harry turned to the other Tuskegee Airmen on the panel with him and said in his quiet voice, “These gentlemen up here with me now. They were there for me; they are my heroes.”

Their missions centered on providing escorts for B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators, the heavy long-range bombers. Under the command of the legendary Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., who would become the Air Force’s first black general, these pilots were ordered with near messianic fervor by Davis to stay with the bombers.

The Red Tail pilots did not let their commander down. The 332nd Fighter Group lost fewer bombers under its protection than had any of the six other fighter groups of Fifteenth Air Force.

Hundreds of heavy bombers, sometimes as many as a thousand, each carrying a crew of 10, flew on raids against targets in cities with war-related industries. The aircraft were layered in massive formations that stretched for miles from front to end, the likes of which were never to be seen again.

Climbing higher than the bombers, typically at altitudes between 20,000 and 30,000 feet, the escort squadrons were stacked a thousand feet above each other, starting at a thousand feet on top of the bombers. Those squadrons flew an “S”-shaped pattern so as not to outrun the slower heavies below.

From his perch riding shotgun well above these flying armadas, Harry was stirred by the sheer magnitude of the assembly, especially on missions where he, as a junior member of his squadron, flew as Tail-end Charlie.

First Top Gun – “Best of the Best”

On July 26, 1948, President Truman signed Executive Order 9981, desegregating the armed forces. The performance of the Tuskegee Airmen and other black servicemen during World War II, such as the truck drivers of the Red Ball Express, the “Black Panthers” of the 761st Tank Battalion, and the “Buffalo Soldiers” of the 92nd Infantry Division contributed to the decision to end racial discrimination in an organization charged with defending freedom.

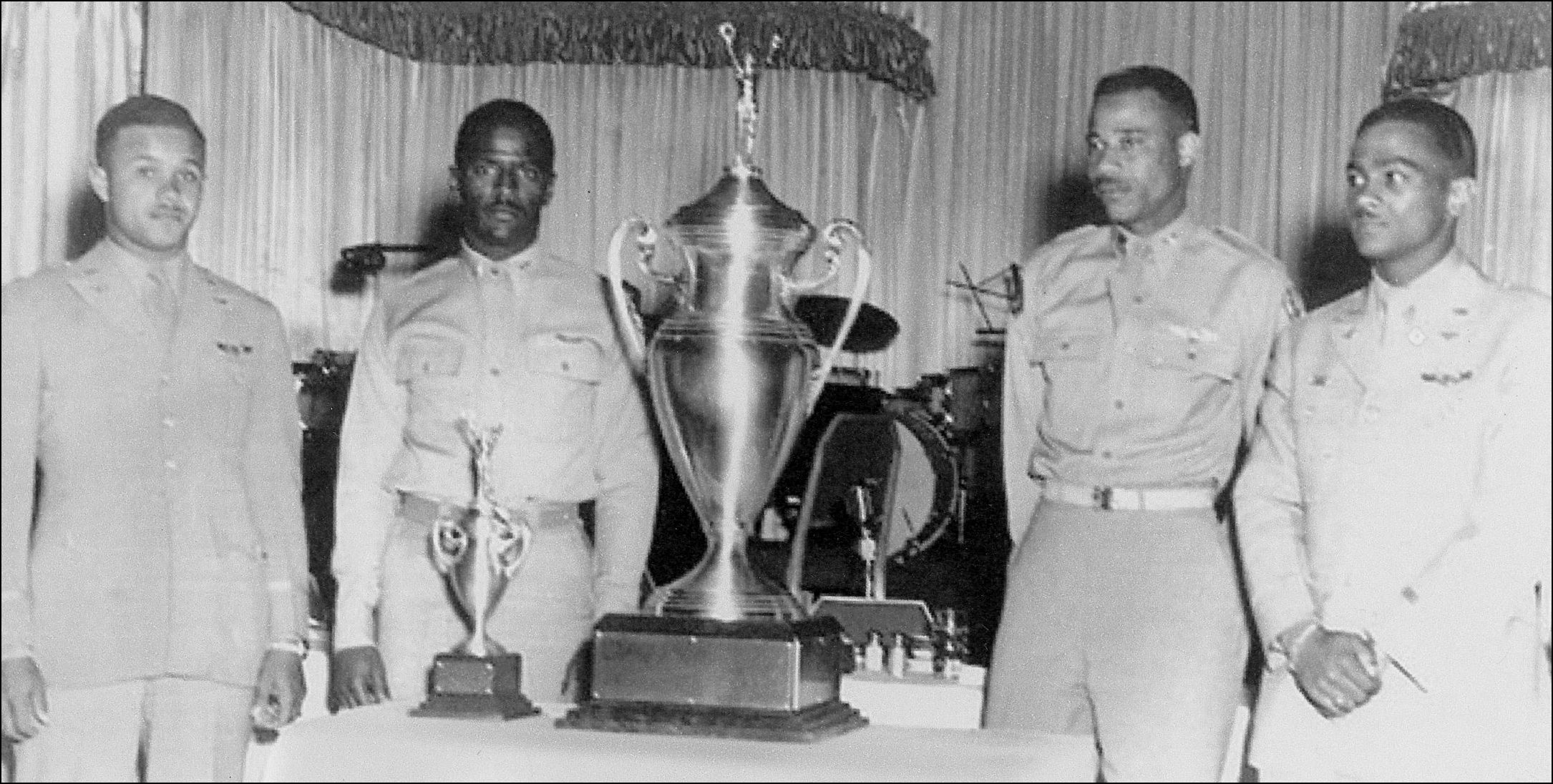

Harry looked forward to serving side-by-side with white service members. Shortly before the order was implemented in the summer of 1949, the Air Force staged its first postwar, nationwide aerial gunnery meet at its sprawling air base north of Las Vegas. In May, Harry and three fellow pilots of the 332nd set out from their home base near Columbus, Ohio to compete on behalf of their unit. Colonel Davis, with a wry grin, told his men not to come back unless they won.

The Continental Air Gunnery Meet pitted pilots and crews from 12 fighter groups across the United States against each other in five categories, from dive-bombing to aerial gunnery, with the competing groups split into two broad classes – jet-powered planes and propeller-driven planes. The 332nd’s team was part of the latter class, with its F-47N Thunderbolts. White pilots competing against them flew in faster P-51 Mustangs.

When the point totals were tabulated, the Tuskegee Airmen had the overall highest score, edging ahead of the team from the 82nd Fighter Group by a four percent margin to win in the propeller class.

At a celebratory banquet at Las Vegas’ Flamingo Hotel, trophies were awarded. It was a memorable moment when the 332nd’s four pilots stood together to be recognized for their accomplishment. In what was perhaps the last major interaction between Air Force personnel of mixed races before Executive Order 9981 went into effect, the Tuskegee Airmen had earned and received the respect of their peers.

Today, the main trophy is on permanent display at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, although it was hidden in storage for 49 years. It has the names of the winners of both aircraft classes from 1949 and 1950, after which the annual event was suspended, due to the outbreak of the Korean War.

LaGuardia Airport: Harry Stewart’s Field of Dreams

Harry’s dream was painfully deferred soon after his team’s trophy win in 1949. The massive post-World War II defense-spending cuts left no place for him in the active-duty Air Force, and, by early the next year, he was consigned to civilian life, though he retained a non-flying commission in the reserves and retired as a lieutenant colonel in the 1960s. The former gung-ho fighter pilot found himself relegated to the role of baggage handler at Penn Station in 1950 to support himself and Delphine, the sister of a squadron mate from Harlem whom he had married in 1947.

Attempts to secure a flight-deck position at Pan American Airways and TWA were futile. Facing the reality of the airline industry’s exclusionary employment practices, Harry turned to education to advance his prospects. After earning a mechanical engineering degree from New York University, he joined the construction firm, Bechtel Corporation in San Francisco and worked his way up to a managerial position. Later, he went to work for ANR Pipeline in Detroit, where he rose through the ranks, ultimately retiring as a vice president.

In retirement, Harry went back to flying. He flew disadvantaged youngsters in the bright yellow motor-gliders of the Youth Flight Academy of the Detroit-based Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Museum. He continued flying until 2005.

Belatedly, the achievements of our black fighter pilots began to receive recognition. In 2007, the Congressional Gold Medal was awarded collectively to the Tuskegee Airmen. Also, Delta Airlines and American Airlines, successor companies to the airlines that had blocked Harry’s commercial air-transport aspirations, made amends by granting him honorary captain’s wings.

Harry will turn 99 on July 4th. It seems only fitting that someone who gave so much to the country has the same birthday as America itself. He is one of only three living World War II air-combat veterans among the Tuskegee Airmen. Sometimes, he thinks about how much things have changed since he spent afternoons at the airport in Queens craving to fly.

It's common to see black airline captains walking through major airport terminals. A black astronaut, Victor J. Glover, Jr., is on the crew roster for NASA’s next Artemis mission, an orbital lunar flight. And the Air Force Chief of Staff, Charles Q. Brown, Jr., a former fighter pilot, is poised to become Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, pending Senate confirmation.

The leadership of the Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Museum has asked that the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey consider naming some part of LaGuardia’s impressive new infrastructure in honor of Harry, a hometown aviation hero. A precedent exists. In November 2022, the Port Authority named the new roadway to one of the terminals at Newark Airport in honor of the late Lawrence E. Roberts, a New Jersey native and Tuskegee Airman.

It has been over a year since the museum submitted its request, and it's still waiting for a reply. The museum would gladly facilitate Harry’s return with one of its rated pilots at the controls of its airworthy North American Aviation AT-6, a rare and historic relic now registered as N42608, which Harry piloted at Tuskegee as part of his training.

With the aged fighter pilot and Queens native seated in the restored military plane’s other seat, and piped into headset communications while cruising toward the airport where his trajectory first got lift, one can imagine how the radio chatter during the journey’s final leg might play out:

Prime mic – click, click.

“LaGuardia Tower, North American 42608, inbound for landing.”

“North American 42608, cleared to land. Nice to have you home, Colonel Stewart.”