After the Revolution, Washington returned to farming at Mount Vernon but eventually called for that he wished a “Convention of the People” to establish a “Federal Constitution”

-

April 1969

Volume20Issue3

Washington had, during 1775, attended the Second Continental Congress as a delegate from what he then regarded as “my country,” Virginia. Virginia was considering a military alliance with the other twelve colonies, but to achieve this was no easy matter. During their long histories the colonies had been jealous of each other, with practically no political connection other than that which was now dissolving: their allegiance to the crown.

In the end, the Continental Congress achieved its alliance by electing George Washington to command the forces of all. Although chosen as the visible embodiment of continental co-operation, Washington, when he assumed the leadership of what was still an overwhelmingly New England army, reacted, upon occasion, like any commander of alien troops. The New Englanders, he wrote, were “an exceedingly dirty and nasty people.” But soon, as regiments came in from other parts of the alliance and he maneuvered them against a common foe, Washington’s allegiance to Virginia gave way to a truly continental point of view. This he brought home with him from the war.

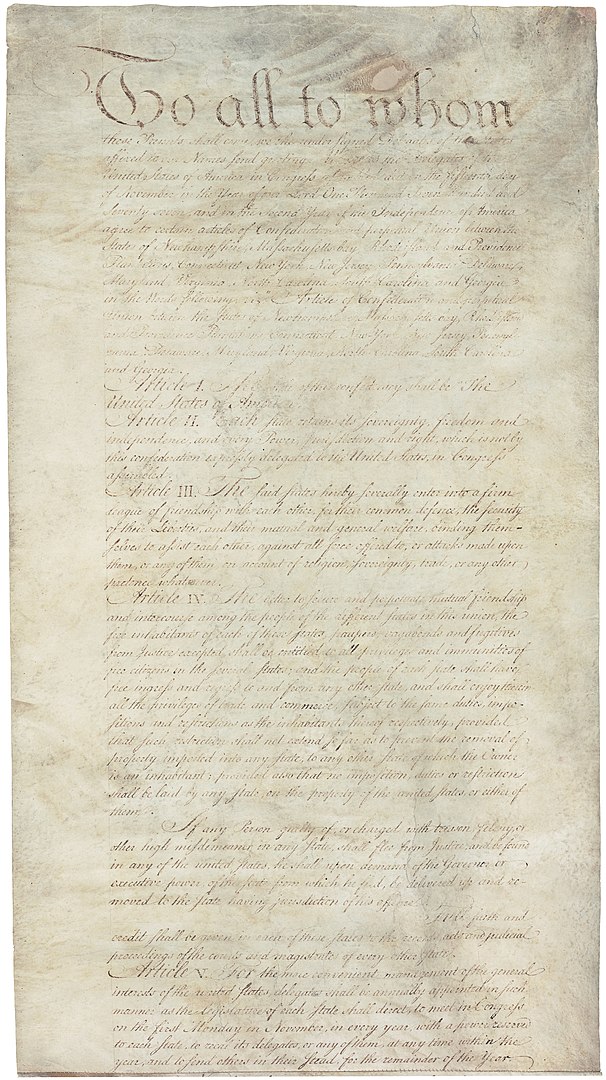

Although other men, including many of the soldiers who had shared Washington’s wartime experiences, had also become convinced during the conflict of the importance of close continental co-operation, the question of whether the United States was one nation or a loose alliance of thirteen had not been resolved. The Continental Congress remained an assembly of different sovereignties, and the Articles of Confederation provided little more than “a firm league of friendship.”

In the early stages of the Revolution, political cooperation had been close, but as the conflict dragged on, and particularly after victory seemed assured, the divisive forces had become increasingly powerful. The states not only failed to meet the expenses incurred by the central body that was directing the war, but refused the unanimous agreement necessary to allow the Continental Congress taxing powers of its own. The army could not be paid; businessmen who had lent money to the central government could not secure even their interest; and the combined dissatisfactions began to coalesce in a manner extremely dangerous to republican institutions. In 1783, Washington was offered the leadership of a movement that could easily have developed into what we would today call fascism.

It was with the greatest difficulty that he prevented the army from joining with the businessmen in terrorizing the governments. Promising to do everything he could, consistent “with the great duty I owe my country,” to procure eventual justice for the soldiers, Washington persuaded them, when they were no longer needed against the enemy, to go home with cruelly empty pockets. The civil creditors were also left in the lurch.

Washington had saved the American republican form of government; this he believed would profit the soldiers more than receiving their back pay. He had also turned his back on the possibility of achieving unlimited personal power. As Jefferson acknowledged, “The moderation and virtue of a single character has probably prevented this revolution from being closed as most others have been by a subversion of that liberty it was intended to establish.”

How much responsibility for making the government function effectively did Washington assume when he persuaded the army and forced the Congress’s civilian creditors to accept present injustice while placing their reliance for future redress on republican forms? His experience had taught him that the rightful debts could not be paid, that the glorious possibilities of republicanism could not be achieved, unless Americans pushed sectionalism aside and learned to act as one nation, not thirteen. While still serving as Commander in Chief, he had yearned for major reforms in the government. In July, 1783, he wrote privately that he wished a “Convention of the People” would establish a “Federal Constitution” that would leave the determination of local matters to the states but provide that, “when superior considerations preponderate in favor of the whole, their [the states’] Voices should be heard no more.”

However, Washington recognized that this conception was still far beyond the present reach of national opinion. In a circular letter to the states which he wrote in June of 1783, Washington publicly urged not the substitution of a new, stronger instrument for the Articles of Confederation, but rather an interpretation and amendment of the Articles that would give the federal government the strength to meet its obligations and establish any necessary central authority.

Eager to give his advice the greatest weight possible, and also anxious to defend himself from any suspicions that political ambitions had made him step outside his authorized military sphere, Washington announced that this, his only major political document to date, was also his last. Once he was released from his military duties, he would never again “take any share in public business.” His advice came to be known as “Washington’s legacy.”

To those who accused him, as disunion became more rife, of deserting a sinking cause, Washington replied that the nation would “work its own cure, as there is virtue at the bottom.” Thus he demonstrated acceptance of the Romantic doctrine that man was not basically evil and in need of restraint, but rather basically good and to be trusted. However, as was typical of his thinking, he gave the doctrine a twist. Repudiating the Romantic conclusion that, since man was naturally virtuous, the best government was that which imposed the fewest restraints, he believed that their virtue would make the American people impose upon themselves, through republican means, the governmental restraints that he considered necessary to secure a strong nation and a just and prosperous society.

Furthermore, Washington did not expect the people to find the right answers merely through inspiration supplied by their natural goodness. “I am Sure ” he explained, “the Mass of Citizens in these United States mean well , and I firmly believe they will always act well , whenever they can obtain a right understanding of matters.” His “legacy” had been an effort to supply such an understanding. However, he did not expect it or any other document to be instantaneously efficacious.

Sure that the people of America would ultimately act for the best, Washington could, after his return to Mount Vernon, watch without too much concern while the states went galloping off in several directions like thirteen half-broken colts. Thus he was consistently sanguine during the first two and a half years of his retirement, for it was only a matter of waiting for “the good sense of the people” to get the better of their prejudices.

Although unwilling to act, Washington kept himself well informed. He interrogated visitors. If newspapers were stolen before they reached Mount Vernon, he complained, and when they did arrive, he denounced them for being “too sterile, vague and contradictory, on which to form any opinion.” He secured from Thomas Jefferson and from Henry Knox, who was commander at West Point and secretary of the Society of the Cincinnati, full reports on what was going on in the East. In congratulating his friend David Humphreys on joining a commission to negotiate trade agreements in Europe, Washington added, “You will have it in your power to contribute much to my amusement and information.” He secured other foreign news through his correspondence with important Frenchmen whom he had become friends with during the war: Luzerne, Rochambeau, Chastellux, Lafayette. It was to Lafayette, in the summer of 1786, that Washington expressed his belief in the future importance of the United States in the councils of the world: “However unimportant America may be considered at present, and however Britain may affect to despise her trade, there will assuredly come a day when this country will have some weight in the scale of Empires.”

In July, 1786, Washington wrote Rochambeau of his belief that “as mankind are becoming more enlightened 8c humanized, I cannot but flatter myself with the pleasing prospect, that more liberal policies & more pacific systems will take place amongst them.”

In fact, at this very time Washington’s confidence was shredding away. Experience, instead of teaching the people effectively to govern themselves, seemed to be giving unpleasant lessons to optimists like Washington. Instead of raising a groundswell for national unity, the years were bringing ever more division. On August i, he meditated reluctantly and sadly: We have probably had too good an opinion of human nature in forming our confederation. Experience has taught us that men will not adopt and carry into execution measures the best calculated for their own good, without the intervention of a coercive power. I do not conceive we can exist long as a nation without having lodged some where a power, which will pervade the whole Union.

Washington was upset that Congress continued to be denied by the states the taxing power that would enable it to have funds of its own with which to operate and pay its debts, and that his soldiers had still not been paid. (The total income of the government in 1786 was less than one third of the interest due annually on the national debt.) Washington was disturbed when New York undermined Congress’s treaty-making power by holding her own land-buying conference at Fort Stanwix with the Six Nations. He was upset because Congress, afraid to take advantage of one of the few powers it actually had, bowed to the states on the question of regulating the settlement of western lands.∗

∗ Washington had long been concerned about the inability of Congress to act for the common good. In March of 1785, because of his interest in a series of canals that would link the Potomac and Ohio rivers, a conference had been held at Mount Vernon between commissioners from Virginia and Maryland to decide the many complicated matters involved in the common use of the Potomac waters. In ratifying the commissioners’ report, which called for delegates from Maryland and Virginia to meet annually, the Maryland legislature decided to invite Delaware and Pennsylvania to the next conference. At the same time, Virginia proposed a meeting of all the states “to consider how far a uniform system in their commercial regulations may be necessary to their common interest.” This led to the Annapolis Convention.

But by far the most serious problems under the Confederation were monetary. Having no mints or stocks of rare metals of her own, America had always been dependent on foreign coins for hard money—“specie.” At the end of the war there had been, as a result of the spending in America by the English and French armies, more specie available than at any other time in the history of the continent. However, there also existed a long-frustrated hunger for European goods. Specie flowed back across the ocean for luxuries; when money began to run out, American merchants bought on credit. The market became glutted, and bust followed boom. What specie did cross the ocean to America was instantly drawn abroad again to pay foreign debts. Practically no currency remained to serve the transaction of local business.

The shortage of money called the fiscal tune. It was particularly hard on debtors. Farmers in newly opened areas, who had borrowed to buy land and tools, often found it impossible, however hard they worked, to raise cash to meet their obligations. Taxes also became extremely difficult to pay. Honest as well as dishonest men lost their farms or were even jailed for debt. The natural reaction was a political protest, which often swung the pendulum too far the other way, wreaking as much injustice on creditors as the debtors had previously suffered.

The various state governments, dominated by directly elected legislatures, soon brought back into existence one of the curses of the War for Independence: paper money. By 1786, seven of the thirteen states had adopted some kind of paper currency.

Washington’s strongest conviction in the realm of finance was a horror of paper money born of his Revolutionary experiences. During the war, inflation had made it impossible to supply the army, had bankrupted the officers, and had brought great wealth to speculators. Furthermore, Washington’s own estate had grievously suffered, since many had paid off their debts to him with worthless paper while he had felt it dishonest and beneath his station similarly to take advantage of his own creditors. During April, 1786, Washington wrote: My opinion is that there is more wickedness than ignorance in the conduct of the States. … and until the curtain is withdrawn, and the private views and selfish principles upon which these men act, are exposed to public notice, I have litde hope of amendment without another convulsion.

The basic problem, so Washington and almost all his correspondents believed, was the irresponsibility of the state legislatures. They swayed like saplings to any breeze, and the prevailing wind seemed to be toward what the eighteenth century called “levelling”—taking away from the established and giving what was expropriated to the poor. Those who were being trampled on could not be expected to submit tamely. Thus the potential political fissure between conservatives and radicals, haves and have-nots, which Washington had spent so much of his energies during the war trying to keep closed, once more threatened to open wide. He had, as the war ended, stamped out a possible military insurrection of the right. Was the nation now endangered by a political insurrection of the left?

Washington and his friends believed that the best preventative of such a fissure and its possible consequence, a civil war, was a stronger federal government that would clip the wings of local demagogues, bring unity where there was chaos, and establish a solid economic base for the nation. The expedient nearest at hand was the convention at Annapolis called for September, 1786, to which all the states had been invited for a discussion of the improvement of commerce.

The Annapolis Convention presented no personal problems to Washington, since no effort was made to make him abandon his retirement and place his prestige behind the meeting as one of Virginia’s delegates. He was indeed too powerful a trump card for the advocates of union to risk on so doubtful a venture.

When from the quiet of Mount Vernon Washington expressed regret that “more objects were not embraced” at the Annapolis meeting than merely trade, back from John Jay came a suggestion that he must have found extremely disturbing. It was aimed at the realization of a strategy which he had long since urged but which threatened to carry him back into the public arena. Might it not be a good idea, Jay asked, to have the Annapolis meeting initiate a call for “a general Convention for revising the articles of Confederation. …”? Jay was “fervent in my wishes” that, should such a convention meet, Washington would, for that “important and single occasion,” return to public life as a delegate.

To Jay, Washington wrote emotionally, “We are certainly in a delicate situation, but my fear is that the people are not sufficiently misled to retract from error.” But while he was not convinced that the time was ripe for calling a convention to remake the government, he was close to despair over the state of the nation. “I think often of our situation, and view it with concern. From the high ground we stood upon, from the plain path which invited our footsteps, to be so fallen! so lost!” Washington made no comment on Jay’s suggestion that he himself get in harness again.

Anxiously interrogating visitors and sending for the mails, Washington awaited word from the Annapolis Convention. The first news was bad: only five of the thirteen states had sent delegations. Then came the electrifying announcement that the delegates had boldly called for a general convention to meet in Philadelphia and “render the constitution of the federal government adequate to the exigencies of the Union.”

Washington hardly had time to wonder whether this effort should not have waited, as he had advised, until some more serious crisis had developed, when there floated in across the autumn landscape reports of a situation so grievous that it seemed as if all effort to bring strength to the government might prove to be too late.

Washington’s first inkling of the new crisis probably reached Mount Vernon with the Pennsylvania Packet for September 23, 1786. A mob of some four hundred men, who were described as ragged, disreputable, and drunken, had threatened a court in western Massachusetts. One insurgent had cried, “I am going to give the court four hours to agree to our terms, and, if they do not, I and my party will force them to it.” The court had adjourned hastily “to prevent coercive measures.”

Soon the mail brought a letter Humphreys had written from Hartford: “Every thing is in a state of confusion in Massachusetts.” There were also “tumults” in New Hampshire, while “Rhode Island continues in a state of phrenzy and division on account of their paper currency.” Washington wrote in reply: … for God’s sake tell me what is the cause of all these commotions: do they proceed from licentiousness, British-influence disseminated by the Tories, or real grievances which admit of redress? If the latter, why were they delayed ’till the public mind had become so much agitated? If the former why are not the powers of Government tried at once?

The news of what came to be called Shays’ Rebellion (after its leader, Captain Daniel Shays) grew increasingly disturbing as the insurgents menaced the arsenal at Springfield, where there were ten to fifteen thousand stands of arms, more than enough to supply an army of rebellion. Congress was considering raising troops but feared that this would boomerang, since the central government lacked money, and, if unpaid, the federal soldiers might join the insurgents.

Secretary of War Knox, who had been sent into western Massachusetts by Congress to investigate, wrote Washington a hair-raising report on the insurgents: ”… they see the weakness of the government; they feel at once their own poverty compared with the opulent, and their own force; and they are determined to make use of the latter to remedy the former.”

The rebels, Knox continued, numbered about one fifth of several populous counties. By combining with people of similar sentiments in Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire, they could “constitute a body of twelve or fifteen thousand desperate, and unprincipled men” well adapted by youth and activity for fighting.

Washington was in extreme agony as winter closed in over his quiet fields. The news that had previously reached him had in no way foreshadowed such a calamity. “After what I have heard,” he wrote, “I shall be surprized at nothing.” Had someone told him, when he retired from the army, “that at this day, I should see such a formidable rebellion against the laws and constitutions of our own making. … I should have thought him a bedlamite, a fit subject for a mad house.” Not doubting that what his friends wrote him was accurate, he found himself menaced by a conclusion to him as terrible as it was “unaccountable,” “that mankind when left to themselves are unfit for their own Government. I am mortified beyond expression when I view the clouds that have spread over the brightest morn that ever dawned upon any Country. In a word, I am lost in amazement when I behold what intrigue, [and] the interested views of desperate characters [could achieve].” Yet he still believed that the majority, even if they “will not act,” could not be “so shortsighted, or enveloped in darkness, as not to see rays of a distant sun thro” all this mist of intoxication and folly.”

Washington’s health, which had been excellent in his retirement, suddenly collapsed. He suffered from “a violent attack of the fever and ague succeeded by rheumatick pains (to which till of late I have been an entire stranger).”

It has become common for modern historians to view Shays’ Rebellion in a sympathetic light. Depression and the shortage of specie had combined, so the historians say, to make it impossible for back-country farmers to pay their taxes and their debts; appeals for relief had been turned down by the wealthier men around Boston who controlled the Massachusetts government; and finally, rather than have their farms expropriated and perhaps be themselves imprisoned, the western farmers were blocking the sessions of courts that might take such action. The insurgents hoped that the protest and the delay would result in their being accorded legal relief.

This, however, was not the story that penetrated by newspaper and letter to Virginia. After Washington had sent Knox’s inflammatory report to James Madison, then serving in the Virginia House of Delegates, Madison wrote back that Knox’s intelligence was not so black as what Madison had heard “from another channel.” In summarizing for his father the situation as it was viewed at the Virginia capital, Madison expressed fear of that violent seizure of property by the poorer classes, which skeptics had prophesied would be the eventual outcome of the democratic experiment.

The fact that Washington, as he rode about his own neighborhood, saw nothing menacing and could write that in Virginia “a perfect calm prevails” did not keep him from believing, as he wrote to Knox, that “there are combustibles in every State, which a spark might set fire to.” Were the Tories and Britains who had foreseen dreadful events, Washington asked, “wiser than others, or did they judge of us from the corruption and depravity of their own hearts?” And he went on, ”… when I reflect on the present posture of our affairs, it seems to me to be like the vision of a dream. My mind does not know how to realize it, as a thing in actual existence, so strange, so wonderful does it appear to me. … When this spirit first dawned, probably it might easily have been checked; but it is scarcely within the reach of human ken, at this moment, to say when, and where, or how it will end.”

A major danger of political life is that extremism, real or fancied, at one end of the spectrum stirs up extremism at the other end: many of Washington’s former officers saw the counterforce to Shays in the Society of the Cincinnati. And the time for the next “triennial General Meeting” of the society was coming around. As he was required to do, Washington summoned the meeting for the first Monday in May in Philadelphia. But he then announced that he would not himself attend or accept re-election as president general. In a circular letter to the various state societies, he blamed this on the pressure of affairs at Mount Vernon, and on failing health. However, he confided to Madison that he was disassociating himself because the state societies had refused to ratify the changes in the society’s charter that he had pushed through at die last meeting. These changes would have removed those clauses which made a potential antirepublican political force out of what he wished to be no more than a benevolent association of former fellow officers.

He had sent to Madison extracts from Knox’s alarming letter in order to prod the Virginia legislature into electing delegates to the convention that the Annapolis Convention had called to revise the federal government. In his covering letter he wrote: What stronger evidence can be given of the want of energy in our governments than these disorders? … If there exists not a power to check them, what security has a man for life, liberty, or property? … Thirteen sovereignties pulling against each other, & all tugging at the federal head, will soon bring ruin on the whole; whereas a liberal, and energetic Constitution, well guarded and closely watched, to orevent incroachments. mieht restore us to that degree of respectability and consequence, to which we had a fair claim, and the brightest prospect of attaining.

Even as Washington wrote these forceful words, he must have foreseen the likelihood of a personally disturbing result: the possibility that he might be called upon to save the nation he had done so much to bring to life. His fears were not long in being realized. Madison’s next letter contained the news that Virginia would probably be the first state to appoint a delegation and that “it has been thought advisable to give this subject a very solemn dress and all the weight that could be derived from a single State.” The legislature had therefore placed Washington’s name at the head of their delegation. Whether Washington ought in the end to accept the post, Madison added soothingly, did not require immediate decision.

To the suggestions he had been receiving that he toss himself into the current crisis by personally going to Massachusetts and stilling the rebellion with his influence, Washington had a sound answer and one that allowed him to remain amid his fields and flocks: “Influence,” he wrote, “is no Government.” If the insurgents had legitimate grievances, either redress them or, if that were impossible, acknowledge the justice of the complaints (as he himself had often successfully done with the army) and explain why no remedy was immediately at hand. If the insurgents did not have legitimate grievances, “employ the force of government against them at once.” Should the force prove inadequate, “ all will be convinced that the superstructure is bad, or wants support.”

The request that he commit his prestige and abilities to the proposed convention menaced more severely his deep-laid plans “to view the solitary walk and tread the paths of private life … until I sleep with my fathers.” Washington was (or had been before Shays’ Rebellion) happier than in any previous period of his life. And he had no faith in the assurances he was being given that he could, after attending the convention, return uncommitted to Mount Vernon. Should he go, he would become again, as he had been during the Revolution, the standard-bearer of a vexed cause, to fall with its failure or be exalted with its success. If the convention failed, the failure would tarnish the shining image which was reflected in the eyes of neighbors and strangers, and which was the great reward he had won with his previous labors. If the convention succeeded, the success would mean—how could he doubt it?—demands for further service to strengthen the government he would have helped to create.

Washington’s immediate reply was that he could not attend the federal convention “with any degree of consistency” because the convention of the Cincinnati, which he had announced he would not attend, would be meeting in Philadelphia at almost the same time. He could not appear at one and not the other “without giving offence to a worthy and respectable part of the American community, the late Officers of the American army.” However, he did not slam the door. As he put it to the governor of Virginia, Edmund Randolph, “… it would be disingenuous not to express a wish that some other character, on whom greater reliance can be had, may be substituted in my place; the probability of my non-attendance being too great to continue my appointment.”

Washington’s perturbation about his own future course undoubtedly mingled with his perturbation about Shays’ Rebellion to raise his anxiety to the fever pitch and led him to write, “What, gracious God, is man! that there should be such inconsistency and perfidiousness in his conduct?” He wondered whether General Nathanael Greene, who had recently died, was not lucky to be dead rather than live to see such times. He held the newspapers that came to Mount Vernon with trembling hands, commenting that they “please one hour, only to make the moments of the next more bitter.”

To put down the rebellion, Massachusetts called out the militia under the command of Benjamin Lincoln, a general Washington himself had trained. There not being money in the treasury, rich citizens subscribed the cost. Lincoln marched, the Shaysites fled, and, with almost no fighting, the insurrection ended.

Although Washington was puzzled as to how a revolt which had been made to sound so ominous could have been extinguished “with so little bloodshed,” his anxiety was not eased. As long as the weakness of the government remained unremedied, the country lay vulnerable to another less controllable insurrection. Might it not, indeed, have been a misfortune that this premonitory disturbance had been stilled before the need for major reforms had been made clear to all? “I believe,” Washington wrote, “that the political machine will yet be much tumbled and tossed, and possibly wrecked altogether,” before the people would agree to such a strong central power as the partisans of the coming convention wished to establish. There were times when he wondered whether wisdom did not urge postponing the convention until there was more hope that it could succeed. Or perhaps the idea should be completely abandoned.

In order to understand Washington’s tribulations, it is necessary to forget everything that is now known about the success and importance of what came to be called the Constitutional Convention. As Washington debated with himself, the name itself could not have been coined; for no one knew that the meeting, if held, would try to write a new constitution. As far as anyone could foresee, the gathering might prove no more than another in the long series of futile efforts that had been made to strengthen federal unity, a series that stretched back into the days of Washington’s military service.

Underlying Washington’s confusion was a nightmarish feeling such as he had experienced during the Revolution when he needed to act but was blind because his intelligence network had failed. The fact that Shays’ Rebellion had come as such an utter surprise to him underlined his conviction that, “scarcely ever going off my own farm,” he was dangerously “little acquainted with the Sentiments of the great world.” He begged for information from those of his friends who had “the Wheels of the Political machine much more in view than I have.” To make up his mind in the manner that was characteristic of him, he needed to weigh the facts on both sides of a question, following in the end the side that tipped the beam.

On the matter of whether it was wise to hold the convention at all, his thoughts ranged widely. If the meeting collapsed into complete failure, might that not be “the end of Federal Government”? Or, if the public proved “not matured” for important changes, the convention might patch up the Articles of Confederation just enough to enable that feeble instrument to stagger along until the situation was past remedy. On the other hand, this might be the final moment when a “peaceable” amendment of the government would be practicable.

Washington’s correspondents wrote him that there was serious talk of grouping the states into two or three separate nations, each unified in interests. There was also talk of abandoning political experimentation by reverting to that well-tried form, monarchy. Much as he disapproved of both of these possibilities, Washingon did not exclude them from his ratiocinations. He admitted that, should efforts to strengthen the federal government seem, on “full and dispassionate” examination, “impractical or unwise,” wisdom might dictate accepting a different form “to avoid, if possible, civil discord and other ills.” Having led one revolution, Washington had no desire to live through another.

His eventual conclusion about the convention was that it should be essayed, not because he thought it could solve all the problems facing the states, but because if the discussions were fruitful it could point the way to a solution. It should “adopt no temporizing expedient,” he wrote to Madison, “but probe the defects of the Constitution to the bottom, and provide radical cures; whether they are agreed to [by the states] or not; a conduct like this, will stamp wisdom and dignity on the proceedings, and be looked to as a luminary, which sooner or later will shed its influence.”

There remained the question whether, if the convention did meet, Washington himself should attend. “To see this Country happy whilst I am gliding down the stream of life in tranquil retirement is so much the wish of my Soul,” he wrote, “that nothing on this side of Elysium can be placed in competition with it.” But the two halves of the picture would no longer fit together. He could not be tranquil while his country was unsettled, yet what should he do?

He did not wish to accept his election as a delegate unless there was a good possibility that something useful could be achieved. His fear of being associated with failure, his belief that it would be more painful for him than for other delegates, has elicited criticism from some writers. Thus, his usually enthusiastic biographer, Douglas Southall Freeman, ruled that he was “too much the self-conscious hero and too little the daring patriot. … He never could have won the war in the spirit he displayed in this effort to secure the peace.”

This judgment would have amazed Washington’s contemporaries. The advice he received from his intimates tended, indeed, to be against his going. Jay, the lawyer, was worried that the convention had been called independently of the amending provisions in the Articles of Confederation: Washington should not countenance what was illegal. Humphreys wished him to stay away because he thought the attendance would surely be small and the meeting a failure. Knox wrote that if it were known that Washington was going to attend, the eastern states would be induced to send delegates, but “the principles of purest and most respectful friendship” made him add, “I do not wish you to be concerned in any political operations of which there are such various opinions.” And Madison, who had been urging Washington to serve, had second thoughts when notified that the General’s decision was tending in that direction. Might it not be best, he asked, if Washington should not appear at once so that, if the opening sessions portended failure, he need not appear at all? “It ought not to be wished by any of his friends that he should participate in any abortive undertaking.”

Everyone knew that if Washington did go to the convention, the greatness of his reputation would make him the most conspicuous member, and his eminence would give him the farthest to fall. In addition to being affectionate, the desire to spare him was both patriotic and pragmatic. Washington was the unsullied symbol of the glorious American Revolution; it would be disgusting to have him splattered with mud. And there was also the fact that his prestige, as long as it was not unwisely squandered, was a mighty lever lying in reserve that could be brought to bear at the right moment. As Knox put it, there might arise some solemn occasion, in which you may conceive it to be your duty again to exert your utmost talents to promote the happiness of your country. But this occasion must be of an unequivocal nature, in which the enlightened and virtuous citizens should generally concur.

Washington’s own reasoning continued to be inconclusive. He had promised in his legacy that he would never again accept public office: if he accepted election as a delegate would he not be accused, and rightly so, of having broken his word? And in early March a new fear formed in his mind: should he fail to attend, would his refusal be attributed to “a deriliction to republicanism”? Could he even be accused of wanting the government to collapse into a tyranny, perhaps one that he himself could lead?

As often happened with Washington, when his mind became more troubled, his health deteriorated. Although he continued trying to calm his nerves with his old panacea of riding restlessly over his land, his rheumatism was sometimes so afflicting that he could not lift his arm to his head or turn himself in bed.

As Washington looked out of Mount Vernon’s windows at the vistas he had so carefully planned and created, as he rode through the fields where he had started so many amusing projects which it would take a lifetime to finish, his beloved home seemed to dim before his eyes, receding again into the unattainable dream that it had become during his eight years of military exile. And the thought of a new exile was driving his wife almost frantic. Martha could not, she admitted sadly, “blame” Washington if, “by acting according to his ideals,” he again shattered their domesticity. But she added with great passion that she had little thought that, once the war was ended, “any circumstances could possibly have happened” which would call him “into public life again. I had anticipated that from that moment we should have been left to grow old in tranquillity and solitude together.”

The news that now came in from across the countryside was good from the point of view of the nation and republicanism, but it was bad for Washington’s hopes of remaining at Mount Vernon. Indications were multiplying that his faith in the people had not been so misplaced as it had for a time seemed. A realization of the need for self-discipline, for effective government, had been slowly augmenting like water swelling in subterranean streams. It had only been necessary to dig a well, and that is what Shays’ Rebellion had done. The nation had overreacted (as Washington himself had) to that small insurrection because tens of thousands of people had already come to feel that the nation was frighteningly vulnerable to chaos. Support for the coming convention grew amazingly. Congress gave the meeting a semblance of legality by endorsing it. And, in state after state, indications pointed to the election of influential delegations. Knox changed his advice, writing on April 9, “It is the general wish that you should attend.”

Washington had already, on March 28, written Governor Randolph that if his health permitted he would accept election to the Virginia delegation. This would require him, he added, to reach Philadelphia a week before the convention opened on May 14, so that he could “account, personally, for my conduct to the General Meeting of the Cincinnati.”

The Cincinnati situation added to Washington’s unhappiness. If he were there in person, he would have to disassociate himself from the decisions of his fellow officers for whom “I shall ever retain the most lively and affectionate regard.”

Washington soon wrote Randolph a second letter in which he repeated his fear that the delegates would arrive so “fettered” by provisos that “the great object” would be unobtainable. He added that he had given his consent “contrary to my judgment,” for his rheumatism had now become so painful that he was carrying his arm in a sling.

The day Washington finally established for his departure, May 8, 1787, moved inexorably nearer. However, “The Weather being squally with showers I defer’d setting off till the Morning.” When on the morrow he stepped into his coach by candlelight, Martha watched unhappily from Mount Vernon’s doorway. “Mrs. Washington,” he wrote down, not without irritation, “is become too domestick, and too attentive to two little Grand Children to leave home.”

Washington rode beyond Baltimore to spend the night at Montpelier, near Elk Ridge Landing, Maryland. He had traversed this region before when vainly seeking shipping that would carry his army and that of his French allies down the Chesapeake to attack Cornwallis at Yorktown. Old strains, old memories crowded in upon him, jostling away the vision of the quiet fields of Mount Vernon. Four days later, after being buffeted by much bad weather and delayed for a night because the Susquehanna River was too storm-agitated to cross, Washington reached Philadelphia. “On my arrival,” he noted, “the Bells were chimed.”

For further reading on Washington and Madison at the Constitutional Convention, see Madison’s Radical Agenda, by Joseph J. Ellis

That Washington set off so reluctantly and sadly to an event which was to be among the supreme ones in American history helped make that event important. Had he leapt to the constitutional call, like a war horse at the sound of the bugle, suspicion would have been raised that the Virginia landholder was serving his interests and those of his class. His long and painful hesitation not only absolved him of selfish motives but, when he felt he could no longer refuse, dramatized the significance of the meeting.

In a letter involving three future presidents of the United States, James Monroe wrote Thomas Jefferson about George Washington: “To forsake the honorable retreat to which he had retired and risk the reputation he had so deservedly acquired, manifested a zeal for the publick interest, that could after so many and illustrious services, and at this stage of his life, scarsely have been expected of him.” And Knox wrote Lafayette, “Secure as he was in his fame, he has again committed it to the mercy of events. Nothing but the critical situation of his country would have induced him to so hazardous a conduct.”