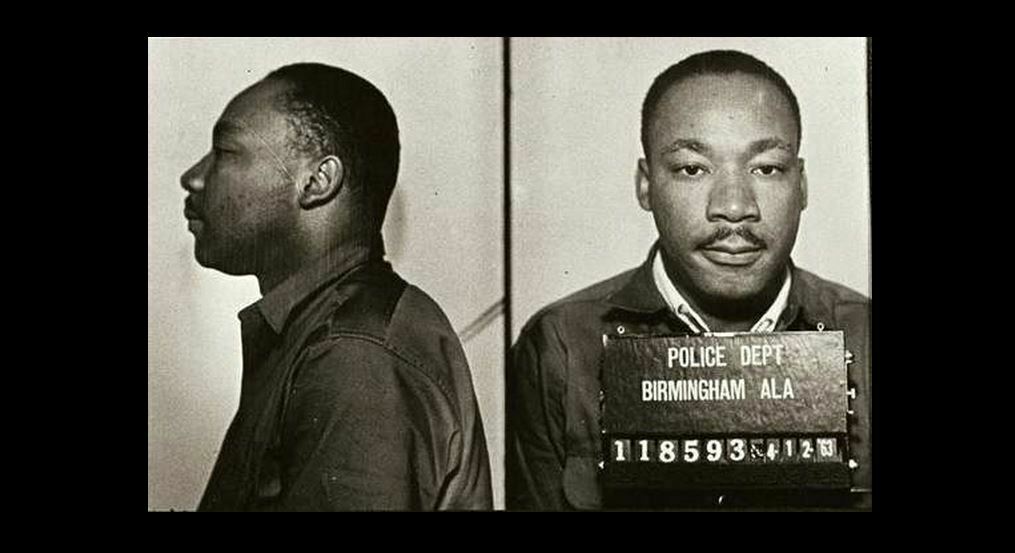

During demonstrations in Birmingham, Martin Luther King Jr. took perhaps the most fateful decision made during the civil rights era.

-

Winter 2010

Volume59Issue4

On April 12, 1963 in Birmingham, Alabama, Martin Luther King Jr., faced the prospect of failure in his most significant civil rights campaign. For all his generally acknowledged leadership in the escalating southern black protest movement, King had actually never initiated a major demonstration.

Depicted in the press as America’s Gandhi, he had disappointed some of his youthful admirers when he declined to join the May 1961 Freedom Rides, and when he left jail on bond after his arrest during the subsequent mass protests in Albany, Georgia. King admitted that the Albany campaign was a “partial victory” at best. “Our protest was so vague that we got nothing, and the people were left very depressed and in despair.”

Birmingham offered an opportunity for redemption, a chance for King and his colleagues in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to demonstrate that they could still give focus and direction to the freedom struggle. Considering the violent history of “Bombingham,” King knew that segregationist resistance would be fierce but a victory would “break the back of segregation all over the nation.”

Despite extensive planning and preparation, however, the campaign ran into a succession of setbacks. Its start was delayed to avoid inadvertently aiding the mayoral campaign of racist police commissioner Eugene “Bull” Conner, who, according to King, “prided himself on knowing how to handle the Negro and keep him in his ‘place.’” King saw Birmingham as “a police state, presided over by a governor—George Wallace—whose inauguration vow had been a pledge of ‘segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!’”

After Conner disputed the apparent victory of a more moderate segregationist in the April 2 runoff, the SCLC launched a series of sit-ins and mass meetings designed to encourage a boycott of downtown white-owned stores. The escalating protests, resulting in more than 400 arrests, discouraged normally brisk pre-Easter retail sales, putting pressure on business leaders and the local community. City officials responded by obtaining a court injunction against further protests.

King was prepared to violate the injunction (something he had never done before) by leading a march on April 12, Good Friday, but soon faced another obstacle when the bondsman announced that he would no longer continue to furnish bail for the demonstrators. King felt responsible for those who were waiting to be bailed, and realized that civil disobedience would be sharply reduced if volunteers knew they would have to endure long jail times until they were tried.

One of his colleagues warned him of the dilemma he faced: “We need a lot of money. We need it now. You are the only one who has the contacts to get it. If you go to jail, we are lost. The battle of Birmingham is lost.” But King knew that not going to jail also held considerable risks. “What would be the verdict of the country about a man who had encouraged hundreds of people to make a stunning sacrifice and then excused himself?”

King soon found himself in solitary confinement

Sitting in Birmingham’s Gaston Motel listening to his colleagues’ conflicting advice, King realized that he faced a crucial test of leadership. “I was alone in that crowded room,” he recalled. Excusing himself from the debate, he went off by himself. “I thought I was standing at the center of all that my life had brought me to be. I thought of the twenty-four people, waiting in the next room. I thought of the three hundred, waiting in prison . . . Then my tortured mind leaped beyond the Gaston Motel . . . and I thought of the twenty million black people who dream that someday they might be able to cross the Red Sea of injustice and find their way into the promised land of integration and freedom.”

When King reappeared wearing jeans, his colleagues immediately understood that he had decided to march. “I don’t know what will happen or what the outcome will be,” King admitted. “I don’t know where the money will come from.”

Rounded up with 50 other marchers by Connor’s police, King soon found himself in solitary confinement and left to endure “the longest, most frustrating and bewildering hours” of his life. Nor could he call his wife, Coretta, who had just given birth to their fourth child.

On Easter Monday King met with his attorney, Clarence Jones, and received news “that lifted a thousand pounds from my heart.” Entertainer Harry Belafonte had raised sufficient funds to sustain the campaign. “In the midst of deepest midnight, daybreak had come,” King marveled.

The Birmingham campaign would face other difficult days, but King’s decision on April 12 would be a decisive turning point. From jail he would write a letter that would become one of history’s most cogent and influential arguments for civil disobedience. After his release, internationally publicized confrontations between thousands of Birmingham teenagers and Connor’s police with dogs and fire hoses prompted President Kennedy to pressure Birmingham’s white leaders to negotiate with King and other civil rights organizers.

When Birmingham officials finally agreed to a settlement calling for desegregation, King achieved not only a local victory but ultimately a national initiative. In June, Kennedy announced that he would submit a comprehensive civil rights bill to Congress.

Civil rights reforms eventually would have been enacted even without King’s fateful decision in Birmingham, but his demonstration of the power of nonviolence undoubtedly shaped the course of America’s racial transformation.

Without King’s courageous action and ultimate triumph in Birmingham, it is unlikely that he would have had been given the chance to deliver his famous “I have a dream” speech. The march itself, if it had occurred at all that summer, would have been much less high-hearted and much more subdued if King had just suffered a major defeat. It is also unlikely that a defeated King would have been named Time magazine’s Man of the Year in December 1963 or would have received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

Of course, King’s moral leadership might have survived a setback in Birmingham, but, in 1963, there were other leaders, including Malcolm X, who were prepared to challenge King’s preeminence, and there was considerable black support for more militant alternatives. King’s current stature as one of his whole nation’s great leaders honored with a national holiday should not blind us to the possibility that the struggle for racial justice in America might well have taken a far more destructive course if King had failed in Birmingham.