Not given credit for their work and paid half a man's salary, women writers won a landmark suit against discrimination at the magazines of Time, Inc., but their success has been largely overlooked.

-

June 2020

Volume65Issue3

In 1967, Time Inc. was the biggest magazine publisher in the world, and highly profitable. Its founder, Henry Luce, was still alive.

Straight out of graduate school, I went to work as a researcher for Fortune Magazine, one of the most prestigious of the four magazines in the Time, Inc. empire, which included Time, Life and Sports Illustrated. Fortune had been founded shortly before the Depression as a celebration of American capitalism, energy, and enterprise by the best writers and photographers that money could buy. Among the early contributors were the poet Archibald MacLeish, the great photographer Margaret Bourke-White, economist John Kenneth Galbraith, and writer James Agee, who toured the South with photographer Walker Evans for a story that became the basis for his classic book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

Fortune was a monthly, and we had a mandate to do whatever it took to get the story, without regard for the travel and expense involved. One Fortune researcher told me that when she flew to Stockholm in the early 1970's she noticed a large American flag flying outside the building where she had an interview.

“Hum, Henry Kissinger must be in town,” she thought. When she entered the building she discovered that the flag was flying for her.

A two-person team of writer and researcher had two months on every story. This usually included a month of reporting and research, two weeks of writing and additional reporting, and two weeks of fact-checking, editing, and re-writing. After a story was finished we researchers were usually given a few additional days to “clean up,” a task that included writing thank-you notes to our most important sources.

All that time gave us an opportunity to dig deep, to get beyond the first level of a story, and often uncover a more complex truth. It was no accident that years later, it was a Fortune writer – Bethany McLean – who first exposed the accounting shell game known as Enron.

The clout and cachet of Fortune also gave us access. Everyone took Fortune’s call. One of our writers was a close friend and frequent bridge partner of Warren Buffet. Several staffers were close to Nelson Rockefeller; one was so close that she had an affair with him.

My own famous-men experiences were definitely less intimate, but still exotic. On my very first assignment, in 1967, I found myself at a dinner in Southern California with Milton Friedman and a group of wealthy Republican trucking executives who were plotting to get Richard Nixon back in the White House. I felt like a spy eavesdropping on a scene out of The Godfather.

Another assignment, on how Lyndon Johnson managed the White House as the country’s “CEO”, took me to the State Department early one evening to interview Dean Rusk, his Secretary of State. Over a glass of bourbon, Rusk explained that he “had no choice” but to keep pursuing the Vietnam War. I nodded, not mentioning that on the following morning, I planned to march with several hundred thousand other people who thought he had a very good alternative – to get out. After our interview, he offered to give me a ride to my hotel. As we glided through the dark streets of Washington in his long black limousine, I hoped that none of the protesters would recognize the car.

On that same assignment, I interviewed the writer Richard Goodwin in Cambridge and he proudly showed me a framed friendly note from Che Guevara, whom he had met at Punta del Este in 1961. A few days later I was in the West Wing interviewing the president’s adviser Walt Rostow, who entertained me with a pointy-stick lecture on all the things the government was accomplishing around the world despite the distractions of war in Vietnam. And HERE, he exclaimed, jabbing the stick at the map of Bolivia, “we got Che.” It was still a secret that the revolutionary guerrilla had been hunted down with the help of Americans.

For four years I had a fabulous job - in many ways, the best I ever had. But there was a fly in the ointment. I was a woman, and as such, very much a second-class citizen. At Time Inc. women were, with few exceptions, confined to a female ghetto, and given almost no opportunity to get out.

The researchers at Fortune were professionals. Many had graduate degrees, and the work involved tough reporting and often complex financial analysis. But we were not quite treated as professionals. The tone had been set by Henry Luce himself, back in the 1940’s, at Time magazine’s 20th anniversary dinner. Here is what Luce said about researchers: “The word ‘researcher’ is now a nation-wide symbol of serious endeavor...Little did we realize that...we were inaugurating a modern female priesthood, the veritable vestal virgins whom levitous writers cajole in vain, and managing editors learn humbly to please.”

When I found that quote, I looked up the word levitous. It means lack of gravity. But those fun-loving, cajoling male writers and editors made two and half times as much money as we did. They worked in offices with windows, doors, and space. Most of us worked in windowless cubicles. When a male writer did a good job he would be promoted to editor, and maybe go on to help run the magazine. When a researcher did a good job, she got a pat on the head and remained a researcher, with no hope of advancement. That was the paternalistic Time Inc. system.

Occasional demeaning incidents came with the job. Once, hours before a story conference was to be held at the University Club, I received a phone call informing me that I – alone of all those working on the story – could not attend. The University Club did not admit women. Another time I accompanied a writer and a Wall St. executive to lunch at the Downtown Athletic Club. Then, as we sat down, I noticed a waiter busily erecting a screen around our table. He was shielding the other diners from the offending sight of me. For those of you who have never experienced such a thing, this hits you like a punch in the gut. You feel it physically. And it hurts.

I might add that sexual harassment was minimal. Fortune was not a garage or a factory floor. The worst that happened to most of us were occasional friendly passes by tipsy colleagues. Tipsy was not uncommon. Recently another former researcher told me about the time a writer she was working with downed 12 gin and tonics at a single sitting. “I don’t feel so well,” he whispered as he staggered to his feet. “I can’t handle the tonic anymore.”

I don’t think the Fortune writers were drunk when they conducted an informal poll on which researchers had the best bodies. The news was leaked to me that I had come in fourth. Out of 28. Far from being offended, I took this as a compliment. We all knew that a boys-will-be-boys attitude was an essential survival skill.

Besides, I thought I had a shot at becoming a writer, which a few women had achieved. I figured that the best way to do that was to — write! So after about three years at the magazine, I went to Central America for a vacation with my boyfriend. While there I spent some time reporting on the newly established Central American Common Market, and when I returned submitted an unsolicited piece to the editors. They liked it, and ran it. The acting managing editor then gave me another assignment – to go to Detroit and see what the city was doing to rebuild itself after the devastating riots. I produced an article and they ran that one as well.

The acting M.E. then called me in and said that as soon as the Managing Editor got back from a Neiman fellowship at Harvard, he was going to recommend that I be promoted to writer. I was ecstatic. But then the editor returned to work, and two or three months went by and ... nothing. I finally went to see my mentor again to see what was happening.

I will never forget the conversation. “Lou thinks you are too good a researcher,” he told me. “He doesn’t want to lose you as a researcher.”

For once I found the right words. It wasn’t a case of what the French call les pensées sur l’escalier, thinking of the appropriate response only as you’re going upstairs to bed.

“I guess I picked the right lifetime but the wrong year,” said I. And I quickly left, headed for the elevators, and went straight to the office of one of the women who were already planning to sue the company for sex discrimination..

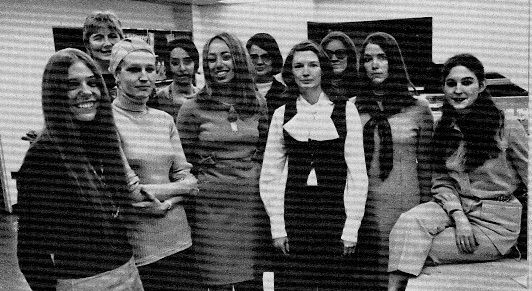

The plot had been inspired by Newsweek’s women, who had just filed a discrimination complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (Newsweek had the same system of female researchers, copied from Time Inc.). By the time I became involved a group of Time Inc. women had already met with a lawyer from the New York State Attorney General’s office, and he had told them that Louis Lefkowitz, the AG, would be happy to represent them. They were in the process of gathering signatures for the complaint and stories of clear-cut discrimination. When I told them my story, I immediately became one of the twelve named plaintiffs.

I later found out that another plaintiff, a more senior woman at Fortune, had a similar story to mine. On her first research assignment the writer with whom she was working had incorporated large blocks of her notes into his story verbatim. After this happened a second time, she went to the managing editor and said she wanted to write for the magazine.

“What magazine?” he asked.

“This magazine – Fortune!”

“Oh yes,” he said. “Of course we would like to give you a chance to write – if you’re between stories and you have some free time. But mechanically that’s going to be impossible because you’re a very good researcher and you’re never between stories.”

“Should I be a lousy researcher, then, to get a chance?” she asked.

She got a tryout. But she was never made a writer. She was later put in charge of story development, a job that hadn’t existed before.

On May 4, 1970, after weeks of secretly accumulating signatures, we were ready. We filed our complaint with the New York City office of the State Division of Human Rights. It charged Time Inc. with discriminating against women in recruiting, hiring, promotion, and indirectly, pay. One hundred and forty-seven women eventually signed.

This was news. The complaint was a legal landmark – the biggest case of its kind since passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Title VII of which outlawed job discrimination on the basis of sex. Not a word about it ever appeared in Time magazine.

The night the complaint was filed, Andre Laguerre, the editor of Sports Illustrated, was at the Ho-Ho restaurant, his usual watering hole, next door to the Time-Life building. Two friends came up and asked if he’d heard the news, that 23 women at Sports Illustrated had filed a complaint.

“Do we have 23 women at Sports Illustrated?” responded Laguerre, who had been Charles de Gaulle’s press secretary.

We had pay data from our union, the Newspaper Guild. Senior researchers with a decade or more of experience, earned the same as beginning writers years their junior. No researcher at Fortune earned more than $18,000 a year. The most junior writer earned the same, while senior writers earned as much as $44,000 a year. The average for people doing a good job was roughly $15,000 for the women, $35,000 for the men.

In sex discrimination cases it is only necessary to prove that jobs for which sex is not a bone-fide occupational qualification (like modeling) have been restricted to one sex. First, we could show that women and men job applicants were sent to different recruiters and channeled into different jobs. And the mastheads told the tale. Time’s masthead listed 67 people as researchers, all female. Only six of the 56 staff writers in New York were women, and only two of those were writing on a regular basis. Of the 104 Time-Life correspondents, only seven were women. No senior editors or higher were women.

At Fortune, 28 women and no men were listed as researchers. Among the 39 editors and associate editors at Fortune, were four women who were writing – after spending six to twelve years as researchers.

At a preliminary meeting, our attorney explained that we would show “probable cause” that the company discriminated against women. One of the editors asked, “what is probable cause?” Our attorney replied, in a thick New York accent, that his masthead alone constituted probable cause.

Management’s rebuttal can only be described as half-hearted. In his statement Daniel Seligman, then senior staff editor for all Time Inc. magazines, said “I would not contend that researchers enjoy as much prestige and pay as writers, but it seems reasonable to point out that by the conventional standards of the marketplace, a Time Inc. researcher has a pretty good job...”

On June 10, the regional director of the New York state Human Rights Division announced that there was “probable cause” to believe that Time Inc. discriminated against women. The next step was for the two sides to try to work out a “conciliation agreement” which was satisfactory to the women. Each magazine was to reach an agreement separately, and if any one division failed to do so, we would then go to a public hearing, something management in particular wanted to avoid. That was our leverage.

At each magazine three representatives from each side got to work. I was one of the negotiators at Fortune, and for several weeks, I spent part of my afternoons sitting opposite our bosses, telling them how things needed to change.

The editors were receptive. Most were politically moderate. They had published dozens of stories supporting the civil rights movement, and now it had landed on their doorstep, in a new guise. They were clearly uncomfortable defending their privilege. Plus, it was an unnerving, almost revolutionary moment. Blacks had been rioting in the cities, students had occupied campuses and burned ROTC buildings, millions had taken to the streets to protest the war in Vietnam and the bombing of Cambodia, and on May 4, the very same day our complaint was filed, four student demonstrators had been shot and killed at Kent State. The times were ablaze, and the foundations were shaking.

This is an important point. Women’s advances have always ridden in on a wave of mass social and political upheavals, from the French Revolution to the 1960’s. What we now call second stage feminism was part of a broad movement for social change, propelled by blacks, students and the young, women, cultural dissidents, political reformers, even welfare recipients. We were not alone. Our demands and our gains were only possible in a climate where old constraints were already breaking down. Literally, for a moment, it seemed like anything was possible. It is hard to describe the heady feeling of sheer possibility that those times unleashed. It is almost inconceivable today to imagine how that feeling of being a part of something historic gave us the nerve to challenge the powers that be. Go see Hair!

And challenge it we did. Politely. There we were, in our suits and sweater sets and high heels, firmly but reasonably asking for a simple fair shake. One woman whose signature I solicited asked anxiously, as she prepared to sign the complaint, “This isn’t a feminist thing, is it?”

“Oh, no, not at all,” I assured her, wondering what on earth she thought feminism was if this wasn’t it.

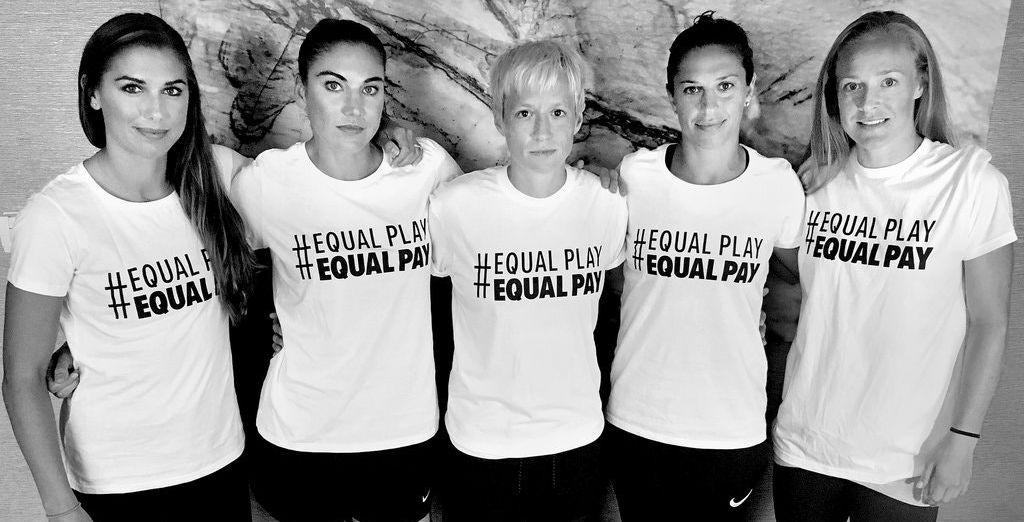

What were our demands? We wanted a chance to prove that we could be writers, through try-outs. We wanted credit lines on the stories we worked on. We wanted experienced researchers to get raises and better titles on the masthead. And we wanted an end to sex-segregated jobs, meaning that men should also be hired as researchers.

One of the editors scoffed at that one, sneering that no man would want a woman’s job. He was wrong. They did, and fifteen years later, a male researcher had risen to become Fortune’s managing editor.

After several months of negotiations, an overall agreement was reached, and at Fortune, management conceded to all of our demands. But I figured that after you sue your company your future probably lies elsewhere. So I went over to Newsweek, which was still under pressure from its own female employees. I was the first woman writer hired at the magazine in response. This was in January 1971.

I had wanted to keep my bomb-throwing past quiet, but a few months later, New York magazine came out with a story on our insurrection, featuring a full-page picture of our negotiators framed as a Time cover. The cover slash read “Man of the Year.” My new boss at Newsweek saw the story and joked that he had hired a bra-burner and a dangerous “women’s libber.” Ha-ha, he said, just kidding. But I’m sure that had the story come out sooner, I would have had a hard time finding a new job.

As a pioneer at Newsweek I soon learned that we still had a long way to go. I discovered that the young man who had previously occupied my new office overlooking Madison Avenue had been earning $26,000 a year. I had been hired at $15,000. Since I was doing the exact same job and seemed to be doing it well – I was complimented in my first weeks by a fellow writer who told me admiringly, “You write like a man.” I decided I deserved a raise. Two months after I started at Newsweek I went to see Lester Bernstein, one of the top editors, and told him that I thought I should have a raise.

He immediately agreed. “We are so happy this experiment has worked,” he enthused. Experiment? What experiment? A woman writing? What about Jane Austen, George Eliot, Virginia Woolf? This wasn’t a monkey playing chess. Did the Newsweek editors really believe that writing for Newsweek was that HARD for a female?

Apparently they did. Susan Brownmiller, who had been a Newsweek researcher in the 1960’s before quitting to become a successful free-lance writer, describes in her book In Our Time: Memoir of a Revolution how Bernstein and others had invited her to lunch after the Newsweek women’s uprising. “Won’t you come back and write for us,” they pleaded.

“We’re afraid that the researchers here can’t be promoted. They may have been too beaten down by the system to have the confidence to make it as writers.”

Brownmiller declined. A few years later she published Against Our Will, the feminist classic on rape, named by the New York Public Library in 1995 as one of the 100 most important books of the 20th century.

I got my raise, to $17,000. I went on to become a foreign correspondent for Newsweek and then in 1975 a reporter for The New York Times, which had just been through its own women’s lawsuit. By then the Time Inc. sex segregation system had completely crumbled, and soon at least 30 percent of the writers at Time and Newsweek and many newspapers were women. I believed that women in journalism had truly made a revolution, and I was proud of having been part of it. I still am.

There is, however, a coda. A few years ago, when I started interviewing people with a view to reconstructing this history, I quickly discovered that not everyone cast the women’s revolt in the same heroic mold. One of the people I spoke with was a woman who at the time was the only female reporter in Time’s Washington bureau. “We didn’t have any researchers in the bureau,” she explained. “Well, we did have one who worked for Hugh Sidey [ Sidey covered the White House for almost 50 years] but she was also his secretary. I thought they were all like secretaries, or something like that. When I heard what was going on in New York, I thought, what IS their problem?”

She did not think we had made a revolution.

I also located the young lawyer and assistant attorney general in the Civil Rights Bureau who had represented us. Dominic Tuminaro confided that back in the day, he had been more than a liberal sympathizer. In fact, he had been a Communist. A Communist party member. An underground party member. Sitting there, over tea and doughnuts in his kitchen on the Upper West Side, I was stunned. What on earth would our bosses have made of THAT? Thank God he could keep a secret!

And there he was, sitting across the table, overlooking West 94th St., telling me HIS version of the story. We thought we were hard-working reporters just trying to get a fair deal, and all along our lawyer was a Red who thought deep down that we were privileged WASP daughters of the ruling class. Certainly we were not the noble and oppressed Norma Raes he would have preferred to champion. (I had a sudden memory of the moment when Tuminaro realized that some of us were actually making MORE money than he was making). But he had eventually rationalized that within the prevailing system, we were, in fact, being treated unfairly, so it was OK to put some energy into our case. Although in his view, we were in no sense a threat to the status quo. We were just rearranging the seats at the banquet.

Tuminaro clearly did not think we had made a real revolution. As I prepared to leave he recommended several books of radical legal analysis for me to study.

Even more stunning was the brief telephone conversation I had with Ralph Graves, who had been Managing Editor of Life during the women’s lawsuit. Graves, the only one of the four managing editors of the magazines at the time who was still alive, had actually negotiated with the rebels from Life. When I told him I was researching the women’s lawsuit of 1970 he said, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“You really don’t remember?” I asked, totally taken aback. “But you were quoted in the New York Magazine piece. You told the women that what they did was good for the magazine. You said “a lot of attitudes have changed, including mine.”

“I was probably just being polite,” Graves replied.

He went on to explain. “I had a lot bigger things to worry about then. Life was losing circulation, we were hemorrhaging money, about to fold....” Which of course it did, two years later, in 1972. So his version of our story was that we were harassing a beleaguered and glorious institution; gnats biting an antelope that had been wounded by a lion.

Except for that lone article in New York magazine, all trace of our – to us historic - civil rights action has been lost. I had assumed that since everyone involved was a writer of sorts, someone would write the history. But no one has. An official three volume history, The World of Time Inc., has been published, and in Volume Three, covering the years 1960 to 1980, there is not a single word about our successful uprising. The author, Curtis Prendergast, told a former Fortune researcher that his description of these events was completely edited out.

Gail Collins’ history of American women from 1960 to the present, When Everything Changed, mentions the Newsweek women’s case but not ours, though ours was a far larger case affecting four magazines, not one. Fifty years later, our excellent adventure has virtually been forgotten.

The case against Time, Inc. wasn't settled until a date for a public hearing was set for January 1971. The potentially embarrassing public exposure prompted management to agree to final terms, which were incorporated into a conciliation order signed by both parties on February 5. Changes that affected women's lives were already underway. Five senior researchers at Fortune were promoted on the masthead, others were given writing assignments, and all were credited with by-lines on their stories. One man was hired as a researcher At Time a woman was hired as a writer, and three men were recruited as researchers. The New York State Human Rights Division agreed to monitor hiring, salaries, and promotion on a quarterly basis.

And Joan Manley was named head of Time-Life Books that year, the first female publisher in Time Inc. history. On the masthead she was Joan D. Manley, but the promotional letters sent out by her office went out over the signature J. Daniels Manley.