I am looking at an old photo of the Lacey twins sharing a chair. Lucy is at the left and Libby at the right. The stains along the picture’s edges are made not by age, but by blood. As R. Scott Jacob of Philadelphia explains it, “When I was a child, my grandmother told me stories of my great-great-grandmother Ida Goodman Wilson and her large family, who lived in a rural community not far from Niagara Falls, New York. One tale was about Ida’s older sister Libby, who my grandmother referred to as ‘the beautiful but tragic Goodman sister.’ She had married a neighbor, Daniel R. Lacey, around the beginning of the Civil War, and a year later, Libby gave birth to twin daughters.

January 2011

In 1937 I was a nine-year-old living on the fifth floor of a six-story walkup in the Bronx. One warm day I went to open the kitchen window and I heard a great deal of noise from the street below. When I looked down, I saw a crowd of people staring up at the sky and pointing.

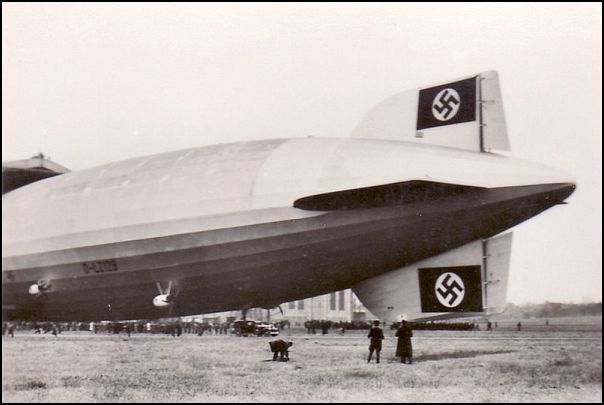

As I turned my gaze upward, I jumped back in horror, bumping my head on the window frame. Just above the rooftops of La Fontaine Avenue sailed the most gigantic behemoth I had ever seen, the dirigible Hindenburg .

It was so enormous and flying so low I felt I could reach up and touch it as it glided by. I called out to my mother to come to the kitchen, and we stood side by side at the window.

My Russian Jewish peasant mother was well aware of how Jews were being treated in Nazi Germany, and when she saw the swastikas on the zeppelin’s tail fins, she said in Yiddish, “Du zolst ontsindn vi a likht [May you burst into flame like a candle].”

I was 17 years old in the early 1940s, a graduate of Theodore Roosevelt High School in Chicago, when the University of Chicago accepted my application. Roosevelt, on the north side of the city, was highly structured with definite rules and regulations, but Chicago—wow!

The university was then operating under President Robert M. Hutchins’s Plan, which postulated that a student could absorb enough information in two years to graduate with a meaningless degree (at least, it was recognized by no other school) whose letters were PHB. We girls changed them in our minds to read MRS, because that was about all it would help us get.

Students were not required to attend classes as long as they passed the comprehensive examinations. These were part of the Plan. At the end of each year, there was one six-hour examination of study, both essay and multiple-choice questions in four subjects. There were no weekly exams, no midterms. One chance a year was all you had. Sink or swim.

It was the late spring of 1959, and my mother had just finished sewing nametags on all my clothes. That was great. It meant I was going to camp. Like most 13-year-old boys, I was impressionable, given to aspirational yearnings, and perhaps more trusting and less savvy than today’s kids. Then I met Gary Kaufman.

Pinelake Camp was in the Catskill Mountains, three hours north of my Brooklyn home. Bunk 16 contained ten campers and one counselor, Gary Kaufman. He was the coolest guy I had ever met. Besides being very nice, he was handsome and what people then called suave, and he had a limitless supply of girlfriends. If that wasn’t enough, he drove a brand-new red Corvette and was on the basketball team at his college. The fact that I’d never heard of that college did nothing to lessen the impact. It was in California, hence exotic and desirable. Two more exotic virtues completed the picture: Gary listened to jazz and was an excellent golfer. We campers worshiped Gary Kaufman.

In 1937, I was a nine-year-old living on the fifth floor of a six-story walkup in the Bronx. One warm day, I went to open the kitchen window and I heard a great deal of noise from the street below. When I looked down, I saw a crowd of people staring up at the sky and pointing.

As I turned my gaze to where they were pointing, I jumped back in horror, bumping my head on the window frame. Just above the rooftops of La Fontaine Avenue sailed the most gigantic behemoth I had ever seen, the dirigible Hindenburg.

It was so enormous and flying so low that I felt I could reach up and touch it as it glided by. I called out to my mother to come to the kitchen, and we stood side by side at the window.

Thank you for the enlightened interview with Ralph Peters by Fredric Smoler, '“The Shah Always Falls.'” I e-mailed my praise of Lieutenant Colonel (Ret.) Peters’s August/September 2002 article “Who We Fight,” but this historical perspective is even better.

Please publish more of his essays in future editions of American Heritage .

I predict you will be bombarded with letters about your Sinatra piece beginning, “How could you have overlooked his great but less ballyhooed, heart-rending poetic refrains of...,” which in my case —and Don Rickles’s too—is the haunting “Summer Winds.”

I’d like to thank David Lehman for his wonderfully written article “Frankophilia” (November/December 2002). Man, you got it! I’m just a punk kid, but reading your essay shone some light on a dreary day. A friend gave me this magazine and said, “Look, it’s Sinatra.” I spent the next hour reading and rereading it until I had it memorized. It’s comforting to know there are others who listen to his music as I do. I love that line “I jump out of bed in the morning singing ‘It All Depends on You’ and your voice comes out of my mouth.” That’s me, right there.

The article “Special Forces” in the November/December 2002 issue was excellent, but allow me to mention that the sidebar, “A Hard School,” was mistaken when it referred to Col. Jerry Sage as commanding the Special Forces School at Fort Bragg. He had a distinguished career in the OSS and became famous in the Army for his repeated efforts to escape from Nazi prison camps. He went on to command the 10th Special Forces Group in the 1960s, and although as commander of the school’s training element he oversaw the training that went on there, he was never its overall commander. His book Sage recounts his remarkable adventures. The character played by Steve McQueen in the film The Great Escape is reputed to be based on Colonel Sage.