January 2011

Gazing up at the Texas night sky from his ranch, Senator Lyndon B. Johnson did not know what to make of Sputnik I, the first artificial Earth satellite launched into orbit by a Soviet missile on October 4, 1957. But an aide’s memorandum stoked his political juices. “The issue is one which, if properly handled, would blast the Republicans out of the water, unify the Democratic party, and elect you President.” Back in Washington Johnson chaired blue-ribbon hearings to determine how the United States had fallen behind in “the race to control the universe.” Whether or not Sputniks were a threat, they were a “technological Pearl Harbor” and a terrible blow to U.S. prestige because “in the eyes of the world first in space means first, period; second in space is second in everything.”

On the evening of July 8, 1959, six of the eight American advisers stationed at a camp serving as the headquarters of a South Vietnamese army division 20 miles northeast of Saigon had settled down after supper in their mess to watch a movie, The Tattered Dress, starring Jeanne Crain. One of them had switched on the lights to change a reel when it happened. Guerrillas poked their weapons through the windows and raked the room with automatic fire—killing Major Dale R. Buis, Master Sergeant Chester M. Ovnand, two South Vietnamese guards, and an eight-year-old Vietnamese boy outright.

On April 26, 1954, six-year-old Randy Kerr stood first in line at his elementary school gymnasium in McLean, Virginia, sporting a crew cut and a smile. With assembly-line precision, a nurse rolled up his left sleeve, a doctor administered the injection, a clerk recorded the details, and the next child stepped into place. “I could hardly feel it,” boasted Kerr, America’s first polio pioneer. “It hurt less than a penicillin shot.”

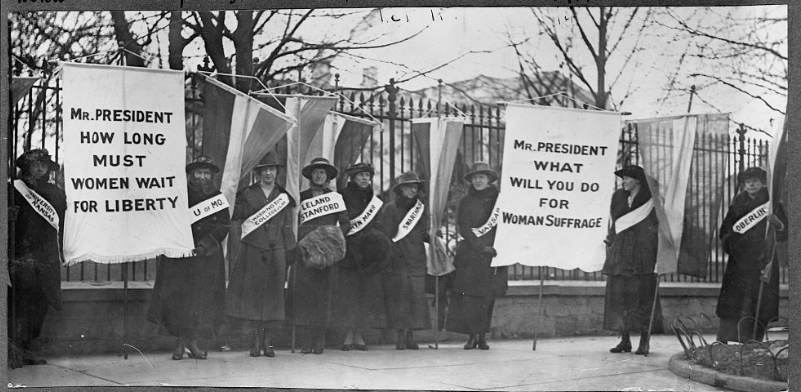

By New Year’s Day 1917, Alice Paul, leader and founder of the National Woman’s Party, had made up her mind. Ever since coming home from studying abroad in 1910, the University of Pennsylvania PhD in political science had observed the ineffective American women’s suffrage movement with increasing impatience. She believed that for women to gain the vote—no matter how radical such a step might seem, no matter the reaction of conservative suffrage organizations—her dedicated followers in the Woman’s Party must picket the White House.

On the morning of October 5, 1905, Amos Stauffer and a field hand were cutting corn when the distinctive clatter and pop of an engine and propellers drifted over from the neighboring pasture. The Wright boys, Stauffer knew, were at it again. Glancing up, he saw the flying machine rise above the heads of the dozen or so spectators gathered along the fence separating the two fields. The machine drifted toward the crowd, then sank back to earth in a gentle arc. The first flight of the day was over in less than 40 seconds.

By the time Stauffer and his helper had worked their way up to the fence line, the airplane was back in the air and had already completed four or five elliptical sweeps around the field, flying just above the level of the treetops to the north and west. “The durned thing was still going around,” Stauffer recalled later. “I thought it would never stop.” It finally landed 40 minutes after takeoff, having flown some 24 miles and circled the field 29 times.

On February 5, 1895, the Jupiter of American banking, J. P. Morgan, took the train from New York to Washington to see the president. He had no appointment but came to discuss matters of grave national interest. The crash of 1893 had thrown the country into deep depression, exposed a schizophrenic monetary policy, and now the nation’s gold standard stood on the brink of collapse.

The origin of the crisis lay more than two decades earlier, when Congress had decreed a return to the gold standard, which had been abandoned during the Civil War. (The gold standard effectively restrains inflation by requiring that a nation anchors its currency to gold at a set price.) In 1878, Congress passed the Bland-Allison Act, which ordered the Treasury to buy the silver then pouring out of Western mines in ever increasing amounts, at market price and to coin it at a ratio to gold of 16 to 1.

On May 24, 1844, Samuel F.B. Morse, a professor at the University of the City of New York, was seated in the chambers of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington when he tapped a message into a device of cogs and coiled wires, employing a code that he had recently devised, to send a biblical text: “What hath God wrought?” Forty miles away in Baltimore, Morse’s associate Alfred Vail received the electric signals and returned the message. As those who witnessed it understood, this demonstration would change the world.

For thousands of years, messages had been limited by the speed messengers could travel and the distance eyes could make out signals, such as flags or smoke. Neither Alexander the Great nor Benjamin Franklin, 2000 years later, had known anything faster than a galloping horse. Now, instant long-distance communication was possible for the first time.

As mayor of New York City and later as governor of New York State, De Witt Clinton crusaded so zealously for a canal connecting Albany to Buffalo that the project became known as “Clinton’s Ditch.” It was a dream of pharaonic proportions—a 363-mile-long artificial waterway that most people considered impossible.

President Thomas Jefferson called it “little short of madness.” Clinton’s Tammany Hall opponents denounced it as a costly folly and depicted it—not incorrectly—as a vehicle for his political ambitions.

On May 5, 1787, James Madison arrived in Philadelphia. He was a diminutive young Virginian—about five feet three inches tall, 130 pounds, 36 years old—who, it so happened, had thought more deeply about the political problems posed by the current government under the Articles of Confederation than any other American.