January 2011

No one likes recessions, but no one dislikes them more than the crooks who are an inevitable part of any financial market.

As the economy goes south, companies seeking to cut costs scrutinize their books more carefully and bring embezzlements to light. Investors take money out of higher-earning (and, therefore, inherently more risky) funds and put them into safer ones, and Ponzi schemes collapse as a result. Credit becomes tighter, and loan requests are more carefully investigated, so businesses with cooked books find their insolvency revealed.

The current recession brought to light one of the longest-running and biggest frauds in the history of Wall Street: Bernard Madoff’s fantastic $50 billion Ponzi scheme, which apparently ran for more than 20 years. Madoff’s fraud may be unmatched in scale and scope, but it’s just the latest of a long string of felonious schemes to hit Wall Street over the more than two centuries of its existence.

On September 3, 1609, Henry Hudson and the English and Dutch men on the 80-ton Halve Maen (Half Moon) came within sight of the coastline where New York meets New Jersey today. The view of the sandy white beach backed by forest must have appeared Edenic to the perhaps 20 gaunt and exhausted men, who had endured most of the past five months crammed inside the 85-foot vessel, savaged by storms, frigid weather, and an oppressive diet.

Four hundred years ago, at almost exactly the same historical moment, two intrepid European explorers came near to meeting in the wilderness of today’s New York State. Each left his name on the waters he visited, but the impact of their journeys left a far larger shadow on America’s history. This year, from New York City up the Hudson and along the shores of Lake Champlain, dozens of towns, cities, and museums will celebrate the quadricentennial of the arrival of Henry Hudson and Samuel de Champlain.

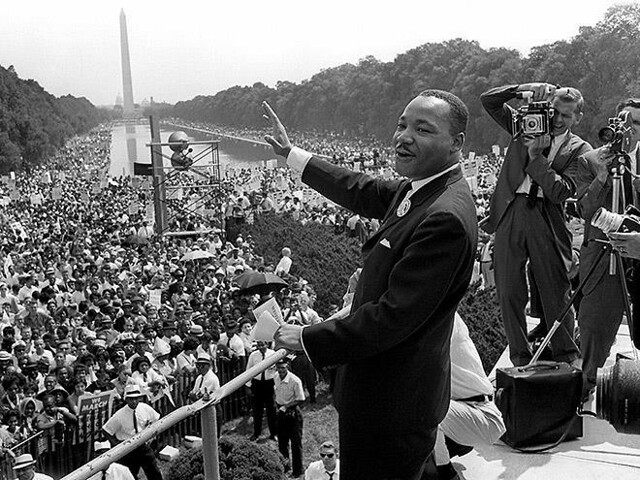

Standing in the cold with 2,000,000 others near the Capitol as Barack Obama delivered his inaugural address, I couldn’t help but recall another crowded day 45 years earlier, when I heard Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” oration at the other end of the National Mall, in front of the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

On January 25, 1859, a small wagon expedition of three whites and 13 blacks stole away from Lawrence, Kansas, on the first leg of a journey that would take the African Americans to the free state of Iowa, far from Kansas and the ever-present threat of kidnapping by slave traders. For the three white abolitionists it was a protest against those who would deny their deepest beliefs about freedom and human rights.

The wagons splashed across the Kansas River and left Lawrence behind. Twelve miles outside town, after the party had descended a small hill, about 20 armed and mounted men emerged from behind a bluff. Guns leveled, they forced the wagons to a stop and accused the white men of stealing slaves. The expedition’s white leader, John Doy, jumped from his horse and confronted a man he recognized. “Where’s your process?” Doy demanded. The man shoved his gun barrel into Doy’s head. “Here it is,” he growled.

The day after Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, while the actor-turned-murderer John Wilkes Booth fled into the Maryland countryside and the nation recoiled in outrage and shock, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton commissioned the famous photographer Mathew Brady to take pictures of the crime scene at Ford’s Theatre. A century later, curators used those images to mount a major reconstruction of the theater and bring it back to its exact 1865 appearance. This February, on the bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth, the Ford’s Theatre Society and the National Park Service completed a second major renovation. “All historical elements of the building have been preserved,” said the Ford’s Theatre Society director, Paul Tetreault, of the $50 million project. The theater’s walls, for instance, remain oddly white, although most theaters feature dark colors.

Last fall, Lake Champlain Maritime Museum’s master shipbuilder, Dale Henry, above, steers the oak-and-pine bateau he built for Fort Ticonderoga into the La Chute River. In the large roadless upstate New York of the 18th century, the scene of much fierce fighting during the French and Indian War and Revolution, the clumsy, flat-bottomed bateau became the vehicle of choice to transport troops. Henry based his replica on the remains of a bateau recovered from Lake Champlain, one of 1,000 bateaux that carried Gen. James Abercromby’s more than 15,000 soldiers on their disastrous offensive against French-held Carillon, later renamed Fort Ticonderoga, in 1758. (See “Battle for the Continent,” by John F. Ross, AH Spring/Summer 2008.) Easy to build and maneuver, even for green soldiers, the bateau slid easily over shallows and shoals, although its weight—at about 1,000 pounds—and two-dozen-foot length made portaging difficult. The bateau is on display at Fort Ticonderoga National Historic Monument,