Paris is every day enlarging and beautifying,” Thomas Jefferson noted with satisfaction during his residence there as minister to France. The city under construction was a delight to Jefferson, the art patron and amateur architect. He had arrived in 1784, determined to commission the finest living artists to glorify the birth of the American republic. Lafayette, Washington, John Paul Jones, and other heroes of the Revolution were to be immortalized by David, or perhaps by Madame Vigée-Lebrun. The sculptor Houdon had already done a bust of Washington; now he was to execute a statue of the Commander in Chief influenced by the equestrian statue of Louis XV in the Place de la Concorde (then Place Louis XV)—“the best in the world” in Jefferson’s judgment.

January 2011

You can tell the difference with a single touch. The stone wall of the actual Alamo, in the center of downtown San Antonio, has a cool, clammy feel, due mostly to the surrounding skyscrapers and tourist attractions casting mountainous shadows over their new dominion. But the Brackettville “Alamo,” facing steady sun and wind-driven sand, is warm and gritty to the touch, and its solitude in the sandy prairie of South Texas gives a flavor that matches our expectations.

The faces of the "American Dead in Vietnam” was Life magazine’s cover story on June 27, 1969. Photographs and brief biographies of the 242 Americans killed in action during one week, from May 28 to June 3, marched on for pages. When the issue appeared, American troop strength in Vietnam was at an all-time high; Nixon had begun the secret bombing of Cambodia in March, and just days before press time he had announced plans to withdraw 25,000 troops from Southeast Asia.

The English writer G. K. Chesterton once observed that journalism largely consists of saying “Lord Jones is dead” to people who never knew Lord Jones was alive. So perhaps does telling the story of the Conway Cabal, a military-political convulsion of 1777 that might have sent George Washington home to Mount Vernon prematurely. It ended up accomplishing nothing, and historians tend to label the affair a nonevent. But a closer look at it provides, for those who find Washington not quite human, a visceral glimpse of him come down from Mount Rushmore as a wounded animal. And the episode has also brought out the beast in historians.

America. The industrial age. Machines, steam, and iron. The picture of progress. But also a nation in mourning. Mourning its Civil War dead, mourning its loss of innocence, and deeply ambivalent about the forces of change. Onto this stage stepped two dapper German cosmopolites—Gustave and Christian Herter—impresarios of interior design and cabinetmakers to the stars. In three centuries of American furniture, there has never been an artist or craftsman who so shaped the taste of the rich and aspiring or whose work so epitomized its age as Herter Brothers. Through its art, Herter Brothers helped America’s newly rich come to terms with their success and, indeed, to flaunt it. Herter’s legacy is one of startling achievement, and it vindicates what is perhaps the most maligned and misunderstood epoch in American art.

The Smithsonian Institution has taken a good deal of heat lately because of some sophomoric pieties formulated by the staff responsible for mounting an exhibit on the Enola Gay and the bomb it dropped on Hiroshima 50 years ago next summer. But the National Museum of American History bears ample witness to the fact that Smithsonian curators can do wonderful things with topics as diverse as bridge building and the great African-American migration from the rural South to the factories of the North after the First World War.

The military section is particularly impressive, containing as it does one of George Washington’s big campaign tents along with an honest-to-God gunboat that served his cause and plenty of muskets and swords and field guns. And of course military equipment always looks fine on display, since it tends to be made of durable material that ages prettily and is usually free of cloying ornamentation. But the most powerful exhibit in the whole section is what at first looks like a drift of incoherent rubbish sealed behind glass.

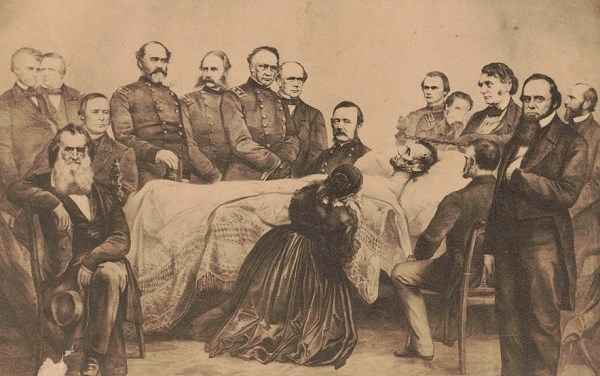

Threat of assassination may seem the greatest risk a president of the United States must take upon entering office, but history suggests that, until recently, a Chief Executive’s life was threatened more by his post-assault medical treatment than by his assassin’s bullet. There have been at least eleven attempts on the lives of American presidents, four of them successful. John F. Kennedy was shot with a high-velocity bullet that destroyed his brainstem, an instantly fatal injury that rendered any medical treatment useless. The three other victims did not immediately suffer fatal wounds.

In 1916, when Margaret Morris was a little girl living in Washington, D.C., she lost her family and they lost her. First her mother died at the age of 41. Then her father, uncles, aunts, sister, brothers, cousins, and even grandmother vanished. This family cleaving left in its turbulent wake a frightened four-year-old who would become my mother.

She was raised by some distant cousins on her mother’s side. And although she married into a vibrant, large, welcoming family, she grieved for the people she had known so briefly. Some of that sorrow she passed on to me. She also passed on all the questions that those who are abandoned or adopted have: Why me? What did I do? Wasn’t I good, beautiful, sweet, or smart enough?

On March 18, 1925, at 3:35 P.M. , I was in the thirdfloor classroom of the Crossville, Illinois, Community High School. As I opened the front door to leave for school that morning my mother called from the kitchen, “Wear your sweater.” When I protested that it was too hot for a sweater, she called back, “This is March. Anything can happen on a March day. Wear your sweater.” By the time I got to school, the air was still and heavy, and my sweater felt uncomfortable. In the afternoon Ol Reiling, the school custodian, burst into our classroom and, ignoring the teacher, said, “Boys, if you’ve never seen a tornado, you’re going to see one now.” In seconds we were crowded at the east windows, looking southward. The teacher was there too. So was Ol.