January 2011

|

Edwin S. Grosvenor, President and Editor-in-Chief |

|

Edwin Grosvenor has edited and managed four national magazines. Portfolio, launched in 1979, was the largest- circulation fine arts magazine in the United States for five years and was nominated for the National Magazine Award for General Excellence. It published writing by distinguished historians, curators, and critics, such as Lloyd Goodrich, Hilton Kramer, Theodore Stebbins, and John Wilmerding. He also published Current Books, a magazine of book excerpts and publications for Marriott and Hyatt Hotels. He is the author of Alexander Graham Bell (Henry N. Abrams, 1997). |

For many years this oil portrait of General Ulysses S. Grant hung in the lobby of the Grand Union Hotel at Saratoga Springs, New York. During all of those years, while the man and his war and his Presidency grew dimmer in the mist of a half-forgotten past, American citizens presumably lounged past the ornate frame, looked up, vaguely recognized the General, and passed on without remark. The painting was made by Ole Peter Hansen Balling, who became a good friend of the General during the time consumed by the sittings. It was painted to show Grant as he was during the siege of Vicksburg.

Iam writing about a subject which in the past has not ordinarily been discussed in public, but the time has come for a public airing of it. Many librarians, collectors, curators, and dealers are called upon in the normal course of day-to-day activities to place a value on a letter, a manuscript, or a book, or on a collection of such items. And on occasion they are required to prepare a document to satisfy the whims of Internal Revenue Service examiners.

This is simply “appraising,” but of late the word seems to indicate to many not the science of placing a true, current, acceptable value on an object, but part of a complex game of wits whose ultimate objective is to confuse, baffle, or outwit one or several exceedingly curious individuals in the Treasury Department. I shall cite a few dangerous examples.

OCTOBER, 1786: “Are your people … mad?” thundered the usually calm George Washington to a Massachusetts correspondent. Recent events in the Bay State had convinced the General, who was living the life of a country squire at Mount Vernon, that the United States was “last verging to anarchy and confusion!” Would the nation that had so recently humbled the British Empire now succumb to internal dissension and die in its infancy? To many Americans in the fall of 1786 it seemed quite possible, for while Washington was writing frantic notes to his friends, several thousand insurgents under the nominal leadership of a Revolutionary War veteran named Daniel Shays were closing courts with impunity, defying the slate militia, and threatening to revamp the state government.

There is something faintly exotic about them, like painted gypsy caravans or those circus carts of fifty years ago that delighted the heart and eye. Yet they were the most humble of vehicles, wagons to carry the ice which kept our grandparents’ meat and eggs from spoiling in the summer’s heat. The firm that built them, the Knickerbocker Ice Company of Philadelphia, announced in its catalogue for 1890-91 that because the ice wagon was the best advertisement for the dealer, “we take great pains in painting and lettering it to attract attention on the street.” What a nice, old-fashioned phrase “to take pains” is, and, as we look at their colors—the orange and red, the yellow and blue and green—we are reminded again of how once even utilitarian things were lovely. The refrigerator ice tray is convenient, but is it art?

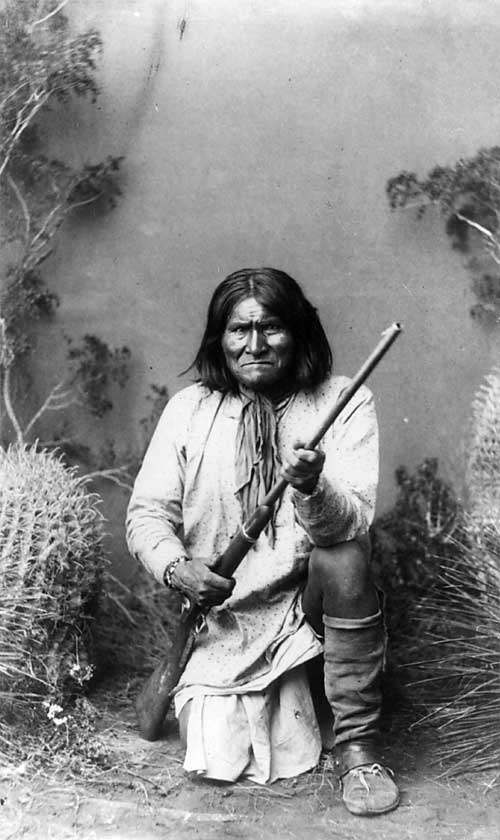

In the forest glade where usually, at this hour, only the dark trunks of great pines were to be seen, he was instantly aware of the shadowy figures of perhaps forty Indians, huddled silently before his tent. Among them Davis recognized the chiefs and subchiefs of the most dangerous Apache band on the reservation: the Chiricahuas.

Once upon a time there was a young republic and it Thought Big. It was located in a big new country which was almost empty of people except for a scattering of Noble Red Men. The government of the republic needed a capital, a place for its head man to live, a legislative hall for talking, and offices for the army, the navy, the treasury, and whatever else they thought of next, such as the Bureau of Urban Dislocation in the National Resources Division of the Department of Health, Wealth, and Wisdom (BUDNRDDHWW). But the government was suspicious of cities, especially old cities. Cities tend to have mobs. As a matter of fact, the government had just been chased out of the last capital by a mob of soldiers who wanted their back pay for winning the war that had made the place a republic.