The literature pants harder and harder to keep up with the proliferation of innovations, but, with a gun to my head, this is for the general reader looking for a short list of books that are technically sophisticated, yet highly readable.

January 2011

Growing up in a family with many members who earned their living on Wall Street, and with many ancestors and relatives who had done the same, I—as might be expected—very early heard stories of business that I found as fascinating as the tales of military action I was soaking up at the same time. The novelist Thomas Hardy explained that “war makes rattling good history,” but it was James Gordon Bennett, the founder of the New York Herald, who explained why business makes the same. Since the Industrial Revolution, with all its new opportunities, Bennett wrote in 1868, “Men no longer attempt to rule by the sword, but find in money a weapon as sharp and more effective; and, having lost none of the old lust for power, they seek to establish over their fellows the despotism of dollars.” The workings of democracy, of course, prevented any despotism from developing, but the battles for success and dominance in the marketplace can be as exciting as any battle for political or military dominance.

In 1800, the United States was an underdeveloped nation of just over five million people. It was a society shaped by immigration, but immigrants from one country, Great Britain, made up around half the population. Although some pioneers had moved west of the Appalachian Mountains, America was preeminently a sea-coast settlement. A prosperous nation, it still lagged far behind England, which was industrializing furiously. And, with only 10 percent of its people living in towns and cities, it was thoroughly agrarian.

“Popular culture” is not the opposite of or the alternative to something called “high culture.” It is not degraded, debased, simple, or undisciplined. Nor is it defined primarily by its mass appeal or commercial values. It is not the size of the audience that is important, but its diversity. In its productions and performances, popular culture brings together into the public space a variety of social groupings: women and men; adolescents and the aged; ethnics and “natives,” white, black, brown, and yellow; rich, poor, and middling; urban and suburban; the over-educated and the newly literate; the established and the recently arrived.

At its best, popular culture is exuberant, sometimes ecstatic; it overflows its formal boundaries; bends, breaks, and reconfigures genres; is often naughty, seldom “nice,” and usually vulgar (but in the largest sense of those words). It can be fun and frightening, engaging and enlightening, acerbic and celebratory. But it is, above all else, a shared or public culture, with its own particular politics.

No one has ever come up with a satisfactory count of the books dealing with the Civil War. Estimates range from 50,000 to more than 70,000, with new titles added every day. All that can be said for certain is that the Civil War is easily the most written-about era of the nation’s history. Consequently, to describe this ten-best list as subjective is to stretch that word almost out of shape. Indeed, my association with two of the ten may be regarded as suspect. My reply is that this association made me only more aware of the merits of these titles.

In a nation of immigrants, picking ten books about the immigrant experience is no easy task. One could plausibly argue that any book about post-Columbian America concerns the immigrant experience. So, I established a few basic guidelines in order to make the job a little more feasible. Some of these, I think, rest on pretty solid ground. I have not, for instance, included any books on slavery. While slaves were certainly immigrants of a sort, their brutal and coerced journey is so different from other immigrant narratives that I think their stories properly belong in a collection of works on the African-American experience.

Other delineations were more subjective. I have not included any accounts of the Plymouth Plantation or Jamestown or the Quaker colony in Pennsylvania. The early colonists were the first immigrants, of course, but their experiences were also fundamentally different from those of everyone who came after them, being stories of conquest and expansion, rather than of adaptation and assimilation.

Americans have always envisioned a west. When they won independence from England in 1783, the west lay just beyond the Appalachian Mountains, a west celebrated in the adventures of Daniel Boone. Then, people began to thread through the Cumberland Gap to make new homes there. Boone felt crowded, so in 1799, he moved across the Mississippi River to take up residence in Missouri.

Only four years later, President Thomas Jefferson bought Louisiana from Napoleon, and the west suddenly leaped the Missouri River and left Boone behind. Gradually, this west yielded its contours to Lewis and Clark, explorers, mountain men, and covered-wagon emigrants. Its boundaries expanded as the war with Mexico and diplomacy with England transformed the United States into a continental nation. By mid-century, popularized by the California gold rush, a geographical west had fixed itself in the American mind: the plains, mountains, deserts, and plateaus that separated the Missouri River from the Pacific shore.

The assignment—to select 10 books suitable for a lay reader that cover American history between the Constitution and the 1850s—sounds easier than it is. There are tens of thousands of books on the period, which saw massive economic, social, and political change, an extension of the United States from the Mississippi to the Pacific, and a series of crises leading to the Civil War. Clearly, my list will have to be idiosyncratic, favoring titles that I have read and loved, that seemed to work well with my students, or that my friends and colleagues praise.

Over the years, moreover, I have come to suspect that comprehensiveness is a recipe for dullness: looking closely at parts of the past is often a better way to understand it than trying to master the whole story. I also prefer accounts from the time over books by historians because they speak more directly to the mind and inspire the imagination. But putting mini-histories in context and interpreting documents requires some knowledge of the period, which gets back to the comprehensiveness problem.

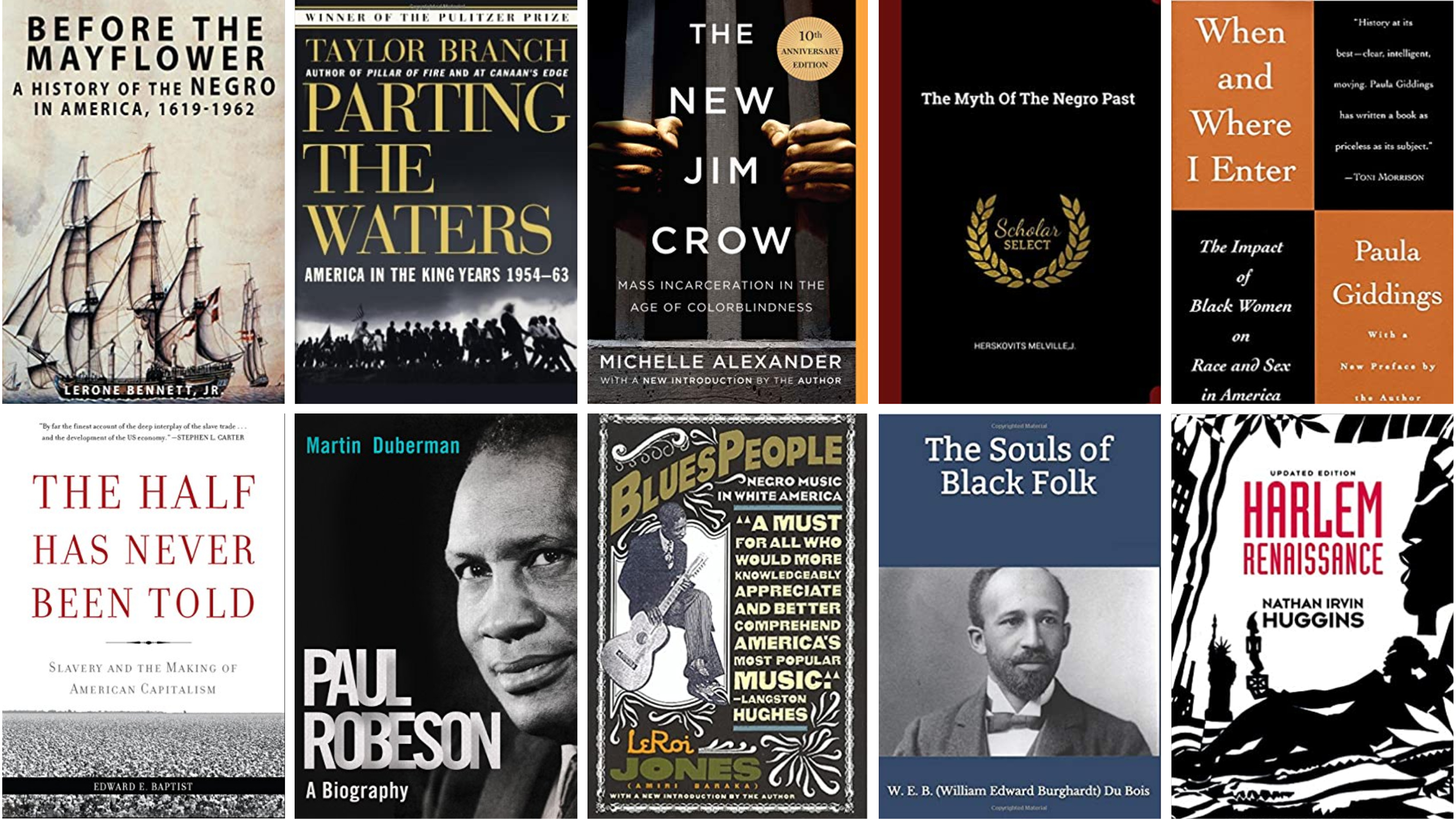

Editor's Note: Amid nationwide protests over racial injustice and a resurgent Black Lives Matter movement, understanding the experience of African Americans in the U.S. is more relevant than ever. So we asked Gerald Early, Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters in the African and African American Studies Department at Washington University in St. Louis, to recommend his favorite books on the history of black America. What follows is a definitive collection of U.S. black scholarship, from one of the subject's preeminent experts.

I’ve been fighting the war of the American Revolution (on paper, that is) off and on since 1962, and my research has included journals, diaries, letters, newspapers, and books on nearly all the campaigns. For the list that follows, I have assumed that a reader is interested in the overall story of the Revolutionary War. (Books about specific campaigns or battles are far too numerous to include.) These are books I have found informative, enjoyable, and, in some cases, worth reading again and again. They are old friends, and, though a number of them were published some time ago, they are reliable.