Walter Cronkite , news commentator: Shortly after the turn of this century a woman who represented herself as a genealogist advertised for anyone bearing the name Cronk, Kronk, Kronkhite, Cronkhite, or several other variations to get in touch with her immediately. She claimed to have knowledge of a longlost will in the Netherlands leaving a considerable estate to the seventh son of the seventh son of one of the original Krankheidt settlers of Manhattan. The ensuing excitement culminated in my grandfather calling a meeting of something he formed called the “Krankheidt Heirs Association.” The convention was held in St. Joseph, Missouri, and, as family lore has it, was a rousing conclave of misfits until it disbanded in confusion when the “genealogist” skipped town with the accumulated registration fees.

January 2011

Librarian of Congress, presidential confidant, Assistant Secretary of State, winner of three Pulitzer Prizes and the Medal of Freedom, distinguished Harvard professor—and incidentally, lawyer and football player—MacLeish was a twentieth-century Renaissance Man, as revealed in this last interview with him

Archibald MacLeish was two weeks shy of ninety when he died this spring. He was born on May 7,1892, in Glencoe, Illinois. His father, a Scottish immigrant boy from Glasgow, in the prescribed Horatio Alger manner founded the successful Chicago department store, Carson, Pirie, Scott & Company and was also a founder of the University of Chicago. MacLeish’s mother had been the young president of Rockford Institution—later Rockford College for Women—when she married. From the start, education played a large part in MacLeish’s life.

For the first time in its twenty-eight-year history, A MERICAN H ERITAGE has opened its pages to advertising. We thus join such publications as National Geographic, Smithsonian , and Scientific American —as well as the overwhelming majority of all American publications—in making a business decision that fortifies our future and takes the burden of increasing costs off the necks of our readers. It is amazing that A MERICAN H ERITAGE was able to hold out for so long, but there is a limit to the price a publisher can charge a subscriber for a magazine, especially one like this, which is physically luxurious and which depends for its existence on writers, illustrators, and photographers of the highest level of excellence.

Just inside the late Pliny Freeman’s 180-year-old barn in Old Sturbridge Village, I recently watched a gray-haired gentleman eyeing with evident disgust a bucket of wormy apples freshly picked from the Freeman Farm’s cider orchard. “Why don’t you spray your trees?” he asked a grimy youth who wore the garb of a New England farmer of 1830 and who helps work the Freeman Farm as if it still were 1830. “We can’t spray the trees,” explained the young man. “It wouldn’t be authentic. They didn’t have sprays in 1830.” The visitor shook his head testily and stalked off in a mild huff. A past with wormy apples was plainly no place for him.

In a special section AMERICAN HERITAGE considers the peculiar glories of the American newspaper. Included are a scorching interview with the Washington Post ’s Ben Bradlee on the use and nature of power—his own, his paper’s, and the government’s; Robert Friedman’s history of the ever-embattled First Amendment; David Davidson’s celebration of the special qualities that made the old World the one paper every newspaperman wanted to work for; an insider’s view of the barbed charms of the country newspaper, revealed by a man who ran one—until he couldn’t stand it any longer. Rockefeller Center … On the fiftieth anniversary of the most successful building complex of the twentieth century, we look at John Wenrich’s soaring, romantic architectural drawings—works of art in their own right- that prefigured the great urban space. Andersonville …

The American press: its power and its enemies …

New England snobbism is based on a regional reverence for that which is old. And as John Gould once wrote, “It takes considerable art to be snobbish without appearing so.” Thus the perfection of a devastating little sign you will see as you enter or leave the old shipbuilding town of Thomaston, Maine. It reads, “Thomaston, 1605.”

Simple. No need to explain that a certain George Weymouth of England founded the town fifteen years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth. In fact, if such an explanation were included, the sign would lose its effect. By becoming informational, it would no longer demonstrate that specific brand of snobbism peculiar to New England.

PIKE COUNTY, KENTUCKY: A fuse that wound back through disputes over a $1.75 fiddle and a stray hog to the well-remembered violence of the Civil War days touched off its charge on August 7. In the midst of Pike County election-day festivities, Ellison Hatfield opened the most famous feud in American history by stirring from a drunken slumber, first to insult Tolbert McCoy and then to attack him. Tolbert and his brother drew knives and started stabbing Ellison; a third McCoy brother shot him.

Ellison, fearfully wounded, was borne away. When word reached Anse Hatf ield, head of the West Virginia clan and to one contemporary “six feet of devil and 180 pounds of hell,” he and his kin rounded up the three McCoys and held them prisoner. Two days later Ellison died; the Hatfields brought the three boys to within sight of one of the McCoy’s cabins, tied them to papaw bushes, and pumped fifty rifle bullets into them.

NEW YORK CITY: On September 2 headlines in The New York Times trumpeted the not wholly unexpected climax to a series of giddy events: “Walker resigns, denouncing the governor; says he will run for the mayoralty again, appealing to ‘fair judgement’ of the people.” The governor denounced was Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had, three years earlier, authorized an investigation into the corruption of the city government of New York, flourishing in the dark shadows cast by Tammany Hall. Walker called the investigations “un-American” and hinted that his opponents were in league with the “Socialists.”

To the left, a blonde, lit by a battery of spotlights, sings into an oddlooking microphone. A pianist accompanies her. To the right, an average American couple stares at a box where, mirabile dictu , the image of the blonde appears. The figures are marionettes, the year 1932, and it is an image of television and the future of America.

The photograph, sent to us by Duncan G. Steck of New York City, was made at the Century of Progress exposition in Chicago. It shows part of a display predicting “the future of television,” created with eerie prescience by the G. & C. Merriam Co., in whose archives the picture has lain for some fifty years. Little is known about the photographer, Albert Duval.

Seven years later, when the New York World’s Fair featured live television broadcasts by NBC, Merriam boasted of its foresight in a company magazine: “It is rather remarkable, we think, how closely that interpretation resembles the latest photographs of actual television broadcasting practice. ” And so, indeed, it has come to pass.

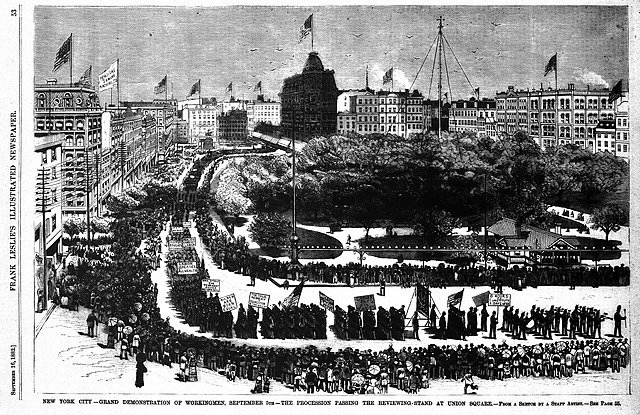

On the morning of the first Labor Day, a century ago, William G. McCabe, who was riding downtown to lead a workmen’s parade through the streets of New York City, found himself in a philosophical frame of mind: he was prepared for the worst kind of failure and convinced that whatever happened could only be for the better. Although McCabe was the grand marshal, the preparations had been made by a committee, and he thought the arrangements were “almost a case of suicide.”