That egg hunters might wipe out the Atlantic loggerhead (Caretta caretta caretta), second largest of the world’s five species of sea turtle, has been a concern for more than a hundred years, or at least ever since the best cooks in Charleston and Savannah began producing pastries from the loggerhead’s leathery-shelled eggs. Thousands were collected each year along the open beaches of the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida—wherever the female turtle lumbered ashore in the full moon of the spring tide to bury over one hundred ping-pong-ball-sized eggs. Time and again the female loggerhead returns from her wanderings on the high seas to deposit eggs on the same stretch of beach, perhaps even returning to the place where she herself was hatched.

January 2011

Presently if you buy a carton of nationally advertised soft drinks you pay from 8 to 14 cents more per carton than if you purchased them in returnable bottles. In addition you will sooner or later have to buy extra garbage trucks to haul them off, or to have them picked off the highways, or perhaps to buy a new tire for your car. I have mixed emotions about them. As a retailer selling them for 61 cents per carton, I make 7 cents. I make 8 cents when I sell a carton of returnable bottles for 51 cents, and the extra 1 cent does not cover the extra costs of handling the bottles. So, as a retailer, I prefer to sell the throwaway bottles. As a citizen, I wonder if they are not one more thing that will in the long run cost more than the convenience is worth. Can you imagine Claytor Lake full of throwaway bottles? Even cans eventually rust. What’s your opinion? L. E. Wade — A box in Wade’s Supermarket’s ad from the April 10, 1969, Christiansburg-Blacksburg (Virginia) News Messenger

“The immediate issue is environmental management. The price runs against our grain. … It includes a social ethic fur the environment; control of the world’s population; willingness to foreswear profits, pay greater taxes and higher prices, reduce the material standard of living, sacrifice certain creature comforts, revise social priorities, and raise sufficient public opinion against principal industrial offenders to compel change. …”

The traveller who leaves Maine on Route 6 and enters New Brunswick at Centreville encounters a curious monument beside the road only fifty feet inside the Canadian border. It is a large concrete slab, ten feet tall and tapering toward its flat, unadorned top. A plaque on its face bears the following inscription:

THIS INTERNATIONAL

MONUMENT

SYMBOLIZES THE BEGINNING OF THE CITIZENS’ WAR ON POLLUTION IN WESTERN NEW BRUNSWICK AND EASTERN MAINE, AND MARKS THE SITE WHERE AROUSED CITIZENS BUILT AN EARTHEN DAM TO STEM THE FLOW OF POLLUTION FROM THE VAHLSING INC. COMPLEX IN EASTON, MAINE

9 JULY 1968

THIS DATE MARKED THE BEGINNING OF

OUR WAR ON POLLUTION

THE WAR CONTINUES

Where once a deep covering of snow meant a world of muffled sound and privacy, it now provides, in more and more parts of the country, a limitless speedway for some one million snowmobiles. The machines, which whine like chain saws, are charging into back-country forests and across frozen lakes heretofore unrcachable in winter except to a few intrepid wilderness enthusiasts, and so, not surprisingly, they are stirring considerable furor among conservationists throughout the country.

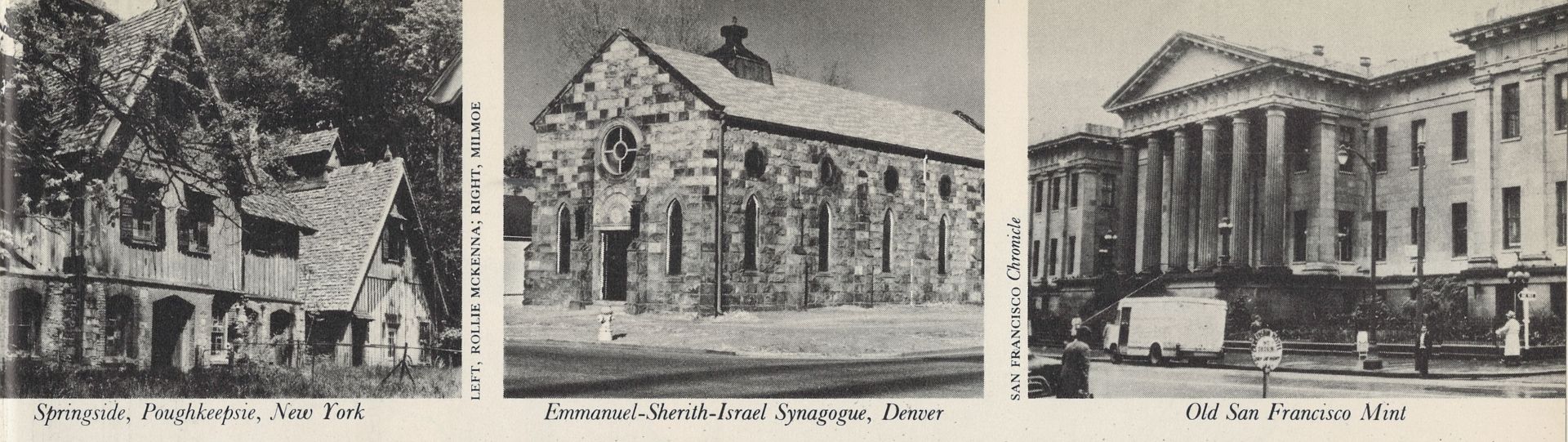

There are places on this earth, in Europe particularly, where conservation is taken to mean the preservation of the notable works of man as well as nature. Magnificent old railroad stations and churches, public buildings, historic houses, architectural landmarks of all kinds, are valued for their beauty or for the memories they evoke, for the sense of continuity they give a place, or, often, just because they have been around a long time and a great many people are fond of them. But here in America we don’t — most of us, anyway — seem to feel that way.

What may come as a surprise is that this swell swoop has been going on for over a century. It was just about a hundred years ago that a relatively unsung hero named Tommy Todd, of Howland Flat, California, was clocked at fourteen seconds for 1,806 feet from a standing start—which averages out to well over eighty-seven miles an hour. Since this was at a time when even crack express trains hadn’t made eighty miles an hour yet, there is every reason to think that Tommy was the fastest man alive in 1870.

For one brief, ten-day period in his life Thomas Alva Edison kept a diary—a most surprising document, personal, fanciful, witty. His spelling and punctuation were erratic, but he wrote in the elegant calligraphy he had taught himself for transcribing Morse code. His wife had died in 1884, and after a lonely year Edison had fallen in love again, in the summer of 1885. He was thirty-eight years old at the time, had three children, and was already famous. It is not known exactly why he decided to keep a diary, why he stopped so abruptly, nor where he was when he began it. Probably he wrote it for Mina Miller—who was to become his second wife that fall—while he was visiting his friends the Gillilands, near Boston, although the first few pages refer to events in New Jersey. The whole diary will be published in facsimile next month by The Chatham Press, with an introduction by Kathleen McGuirk. A MERICAN H ERITAGE here presents, also in facsimile, the first entry of this charming document, for July 12, 1885.