The funeral of Samuel Colt, America’s first great munitions maker, was spectacular—certainly the most spectacular ever seen in Hartford, Connecticut. Jt was like the last act of a grand opera, with thrcnodial music played by Colt’s own band of immigrant German craftsmen, supported by a silent chorus of bereaved townsfolk. Crepe bands on their left arms, Colt’s 1,500 workmen filed in pairs past the metallic casket in the parlor of Armsmear, his ducal mansion; then followed his guard—Company A, izth Regiment, Connecticut Volunteers—and the Putnam Phalanx in their brilliant Continental uniforms.

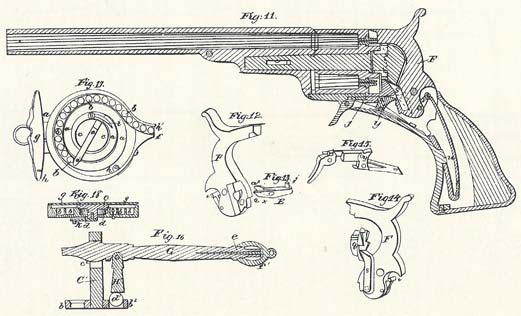

Samuel Colt's design for the Colt Paterson Revolver was patented on August 29th, 1839. Colt enjoyed a domestic monopoly on revolving firearms well into the 1850s.