January 2011

The grim and vivid account which follows may strike some of our readers as a frightful fantasy. Unfortunately it all took place, detail for detail, in the year 1911. Since we believe, as this magazine regularly testifies, that the good in our past generously outweighs the bad, we never shrink from chronicling cruelty and rascality. Yet we might hesitate, even so, to print this unusually ugly story of racial violence long ago if it did not lay bare so much that lies dangerously hidden in the folk memory of the white man and the black, if it did not help in some way to explain some of the bitterness and guilt which presently afflict the two races, if it did not admonish us so powerfully—if, in short, good did not sometimes spring out of evil.

In this country there are no classes in the British sense of that word, no impassable barriers of caste.… Our society resembles rather the waves of the ocean, whose every drop may move freely among its fellows, and may rise toward the light until it flashes on the crest of the highest wave.

—James A. Garfield, 1873

In this country there are no classes in the British sense of that word, no impassable barriers of caste.… Our society resembles rather the waves of the ocean, whose every drop may move freely among its fellows, and may rise toward the light until it flashes on the crest of the highest wave.

—James A. Garfield, 1873

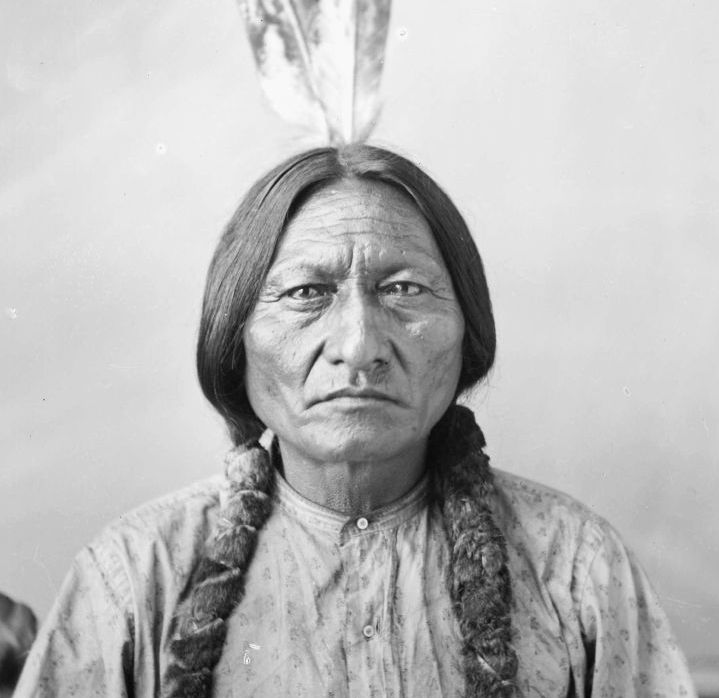

If Sitting Bull had not put his faith in a miracle, in the fateful winter of 1890, the American struggle with the Dakota Sioux—the last big Indian “war”—might have faded into a peaceful if pathetic accommodation between conqueror and conquered. But a miracle seemed the only refuge for the great old chief in that bitter season of a bitter year; and he thought he saw one coming.

When news of the destruction of Big Foot’s band at Wounded Knee reached the Pine Ridge Reservation, the Sioux under Red Cloud—after Sitting Bull the most influential of the Dakota chiefs—immediately fled into the Bad Lands. What follows is an excerpt from the memoirs of Lieutenant Charles W. Taylor, who commanded a company of Indian scouts during the final negotiations.

Additional troops had been hurried from a distance and a cordon practically established around the Bad Lands. … Through the scouts, daily touch was kept with the hostile camp and all that transpired there. Messages began to come but all were ignored except those directly or indirectly from Red Cloud. This wily, experienced warrior recognized the uselessness of further resistance, and acted accordingly. …

The Battle of Germantown, on October 4, 1777, was a confusing affair. Washington’s troops struck a surprise blow at the Philadelphia suburb, overrunning the enemy outposts at dawn before sleepy British grenadiers could figure out what was happening. In the morning mist two units of the heavy American attacking force mutually mistook identities and wasted a good deal of ammunition on each other; and General William Howe himself, riding hastily out from Philadelphia, wrongly assumed that nothing but a rebel scouting party was involved—until a few rounds of American grapeshot began to “rattle about the commander in chief’s ears,” as one of his officers put it.