January 2011

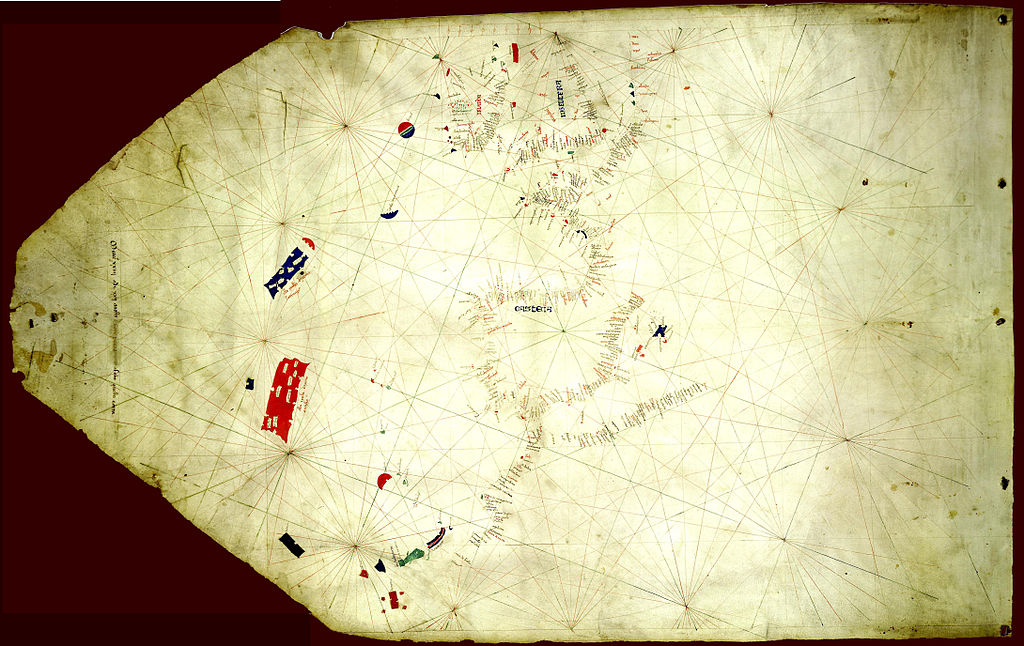

Editor's Note: The last issue of AMERICAN HERITAGE reported the publication in Europe of an ancient map giving evidence that the Western Hemisphere was discovered by Portuguese explorers before Columbus. This map, whose history and meaning are discussed in the following article, is here reproduced in color for the first time in the United States.

A few years ago Bill Mauldin drew a cartoon to commemorate an unsung hero: a gardener at Hyde Park who had firmly resisted the temptation to write his memoirs of President Roosevelt. Undoubtedly Mauldin’s gardener was indeed a hero to a reading public wearied and bewildered by the apparently endless outpouring of memoirs and diaries about Roosevelt and the New Deal. In the ten years since Roosevelt’s death, the number that have appeared is so large that it bids fair to rival the quantity on Lincoln and his administration.

From the President down, most of the New Dealers had a keen sense of history, and many of them were ambitious to record their roles in the stirring events of their times.

Musical Americana

Songs and ballads closely connected with American history bring the past to life on recent long-playing recordings. Three new releases from Folkways (117 West 46th Street, N.Y. 36) continue the series of historic music started with Ballads of the American Revolution .

After having been in storage for nearly a century, an important and invaluable collection of furniture, paintings, silver, jewelry, and over 85,000 manuscripts of the Livingston family has been acquired by the New-York Historical Society. Included are the personal papers of Chancellor Robert R. Livingston, who, as Jefferson’s minister to France, 1801-04, negotiated the Louisiana Purchase and, with Robert Fulton, promoted the first successful commercial use of steamboats. The collection, presented by Mr. and Mrs. Goodhue Livingston, has never before been available to historians. “The Liberties of America are an infinite stake,” wrote Alexander Hamilton in a letter of June 28, 1777, to Chancellor Livingston. “We should not play a game for it, or put it upon the issue of a single cast of the die,” he adds, justifying Washington’s tactics. “Living in our capital [New York] is become so very expensive, and what its worse . . . it is become fashionable. Surely this must be very pernicious,” laments Robert Livingston, Third Lord of the Manor, to his son Walter on April 6, 1785.

What is history, anyway—a sober recital of names and dates, with weighty analyses of economic forces and political trends woven in, or a simple attempt to introduce the past to the present in understandable human terms? The answer, probably, is that it is both; but it must be remarked that the professionals have left the second field wide open and that the amateurs occasionally come in and do a job that might otherwise be ignored altogether.

Thus we have Arthur Loesser, a first-rate concert pianist by trade, who doubles in brass (so to speak) as music critic for the Cleveland Press , writing Men, Women and Pianos , with so much wit, perception and general clarity that the result is a genuinely first-rate examination of the habits, customs and emotional and industrial development of European and American society over the last two centuries.

The essence of an historic tragedy is that although we can see it coming we know that nothing can possibly be done to avert it. It is the result of a whole chain of events, and the chain can be extremely loose; it could be broken anywhere—by sheer accident, by the action of someone possessing just a little foresight, by any one of a dozen things which could so easily happen but somehow do not. In the end the tragedy occurs, in spite of logic and probability. We know it is going to happen, but until the moment of catastrophe we hope, in spite of what we know, that the story will turn toward a happy ending. It never does—and history goes on to some other tale.

It is this built-in quality of suspense and growing doom that lends a peculiar flavor of excitement to Jim Bishop’s excellent new book, The Day Lincoln Was Shot .

No American ever stands very far from the sea. Back of every one of us there is a long ocean voyage. Except for full-blooded Indians, all of us came here by ship. No matter how far inland we may go or how long we may live there, we carry with us a racial memory of the wonder and peril of the empty sea—the feeling that all certitude has been left behind, and that what lies ahead is incredible wonder and the bright chance of a new world. Probably no single thing in the American consciousness lies deeper than this.

So there is in our heritage—as there is in the heritage of no other people on earth except the Australians, who are quite a bit like us in many ways—a sharp dividing line, a point at which the men and women whose blood we carry cut themselves off from all of the old ways and went west to take a long chance.