January 2011

Sun Valley Resort (1-800-786-8259; www.sunvalley.com ) offers a wide range of accommodations and packages, from rooms at the lodge and the inn to condo apartments with full kitchens, and a variety of restaurants; the finest, the Lodge Dining Room, serves, among other things, fresh Idaho trout and an extraordinary rack of Idaho lamb. Ketchum is also full of good places to stay and to eat; for instance, the Ketchum Korral Motor Lodge (1-800-657-2657) has log cabins where Hemingway used to stay in the 1940s before the lodge opened for the season. The best restaurant in town, by general acclaim, is the Evergreen (208-726-3888), which often makes lists of top eating places nationwide.

In the last quarter-century, the American steel industry—once the very symbol of American economic power—has undergone wrenching change. While steel production has declined somewhat (from 131.5 million tons in 1970 to 105.3 million in 1996), employment in the steel industry has declined much more. There were 457,000 workers in the industry in 1975. Thirteen years later, there were only 169,000. Today there are 162,000.

This painful example of the “creative destruction” of capitalism resulted from two factors. The first was that lower shipping costs (and, often, disguised government subsidies) made it increasingly possible for foreign-manufactured steel to compete with domestic steel in the open American market. Even more important was the spread of “mini-mills,” which process scrap steel instead of iron ore and use electricity to power their furnaces. They were able to produce many kinds of steel far more cheaply than the oldline steel mills dating from the Carnegie era.

It all seemed familiar: the sobering headline, the quick survey of responses from Washington and other capitals, then the solemn editorial assessments of the meaning of it all. Last spring, India—showing what Secretary of State Madeleine Albright called “reckless disregard for world opinion"—conducted underground explosions of five nuclear “devices,” that euphemistic shorthand for bombs. Then Pakistan, despite entreaties and threats of U.S. sanctions, responded with five blasts of its own, claiming that India’s action left it little choice. The meaning was all too clear: India and Pakistan were opening an apparent nuclear arms race, just when the world was breathing easier after the end of the Cold War.

It is a phrase so high-concept that it ought to be the title of a movie, or at least the slogan for a marketing campaign, the ultimate coming attraction. Never mind Intolerance or Citizen Kane, the real Movie of the Century would be a will-o’-the-wisp, always just about to be revealed, a hundred years in the making, cast of millions, coming soon to a theater near you. What drove movies in the past was anticipation of what the future held. In the years when Hollywood was actually producing a fairly steady flow of good-to-great movies, there was scarcely time or inclination for a backward glance.

This engaging article about Warren G. Harding released me from a near lifetime of shamed silence. When I was a child, my grandmother told me that I was related to President Harding; sixth cousin twice removed, she said I was.

Early in the school year, in hopes of securing the admiration of my fellow third graders, I announced to them my important connection to Warren G. Our (nasty) teacher, Mrs. Rosenfeld, overheard me and, smiling sweetly, said, “Of course you know he was the worst President we ever had.” I hardly ever spoke of him again. But as I grew older (and witnessed several Presidencies), I wondered: Was Harding that bad?

August 28, 1915, was Lillian Anthony’s last day of work as a bookkeeper at the United Shoe Machinery Corporation, in Beverly, -Massachusetts. She was leaving, her daughter-in-law, Shirley N. Boothroyd, explains, to marry Frank Boothroyd, an electrician for United Shoe, and her co-workers had prepared a party for her. Lillian bears a dusting of confetti, and the workaday oak desk is festive with gifts, among them a most prescient one, a pair of identical china dolls.

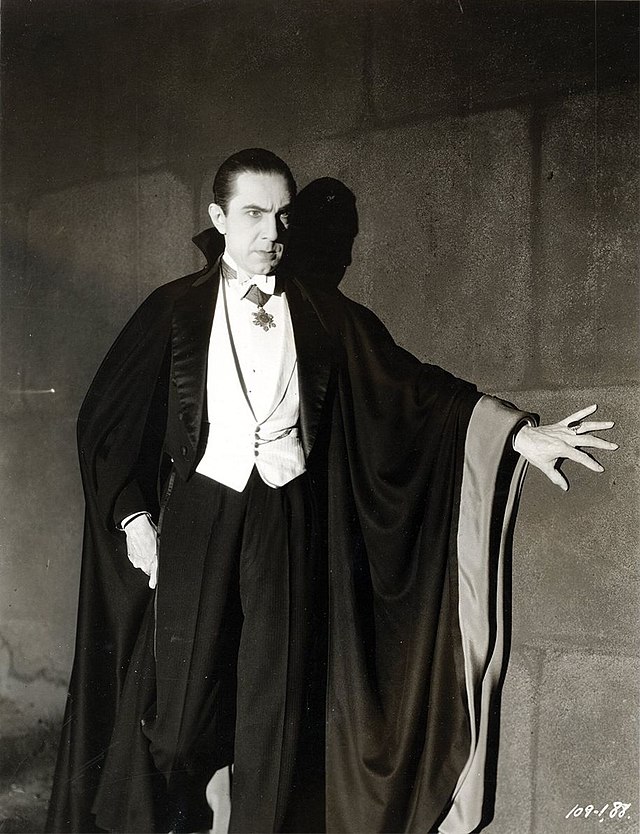

It is hard to believe now, but there was a time when moviegoers did not know about vampires. Didn’t know you do them in with a wooden stake through the heart, didn’t know a ray of sunlight is injurious to their health, that they sleep in coffins all day, and go about at night as bats and wolves. Didn’t even know they drink the blood!