January 2011

The QE2 will make twenty-four transatlantic voyages through the rest of 1996. For information call (1-800-221-4770). Each year, in the spring and the fall, a number of other ships (including several Cunard vessels) offer “Repositioning Cruises,” taking them from European waters to the Caribbean Sea or the Pacific coast. This allows passengers, often at very favorable prices, to sail the Atlantic (generally following a calmer, southerly route) on voyages made up of long, leisurely days at sea and few or no ports of call. Call the following lines for details: Sun Line (1-800-368-3888), Royal Caribbean (1-800-327-6700), Royal (1-800-227-5628), Radisson Seven Seas (1-800-285-1835), Silversea (1-800-722-9955), Costa (1-800-462-6782), Crystal (through travel agents only), Holland America (1-800-426-0327), Princess (1-800-568-3262), Seabourn (415-391-7444).

For those who did not have the means to spend their days in deck chairs and their nights under gently swaying chandeliers, the Atlantic passage had a very different meaning. One such was Karl S. Puffe, who was born in 1858 in a small town in a corner of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire that now belongs to the Czech Republic. He married a childhood sweetheart, Pauline Weidlich, in 1881. A hard time followed. “For the next ten years,” writes his grandson Forster D. Puffe, “my grandmother gave birth to three daughters and five sons, of whom six died in infancy, two in one week. During that same period my grandfather also buried both his parents and his wife’s widowed father. Those heartbreaking experiences coupled with his family’s difficult living conditions made him decide to begin a new life for his family in America.

IT’S SAID THAT FLANNERY O’CONNOR WAS THE first graduate of a university writing program to stake a claim to major-writer status. Dinesh D’Souza is a similar figure for the intellectual policy-journalistic training-and-support network that the conservative movement created in the 1970s. He was an enfant terrible at the Dartmouth Review, the earliest of what is now a substantial string of outside-endowed campus conservative magazines; worked in the Reagan White House; and, in 1991, published Illiberal Education , one of the formative attacks on “political correctness” in universities. He is now a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., and a lecture-circuit stalwart. There are plenty of conservative intellectuals around, but he’s arguably the only one to have been groomed from birth (well, freshman year in college) and have gone on to write big, ambitious books.

While fully and freely admitting that my knowledge of the field is not much greater than George M. Cohan’s, I will say that a great many CD-ROMs look pretty feeble to me. They are so widely promoted as the path to the future that every enterprise seems to be straining to cast its information beneath that gleaming surface, and often enough the result is: a stupid and complicated way to consult an encyclopedia; a stupid and complicated way to look up batting averages; a stupid and complicated way to plan a vacation.

I did not say any of this during meetings over the past months with the people at Byron Preiss Multimedia, who were assembling a CD-ROM that would bear our name, American Heritage: The Civil War—The Complete Multimedia Experience, but my heart was honeycombed with doubt. Then, last week, I saw the result of our long collaboration, and I was both impressed and chastened.

A rich variety of fences is one of the many charms of the American landscape: the wooden rail fence of the rural Midwest and South and the picket fence of the town, crude barbed wire surrounding prairie fields and ornate iron palings protecting village lawns, the New England stone wall running through abandoned farmland grown back to forest and the chain-link barrier screening weed-infested lots in the downtown fringe. Another classic American type is defined not by form but by function. Yet because its form follows its function with a rigor that Louis Sullivan would have admired, it is as easy as the others to recognize. Its purpose is summed up in its name: the spite fence. It is meant to irritate and to harm, blocking the light and air and obstructing the view from the windows of a neighboring house, making that property’s occupation less pleasant and its rental or resale less lucrative. A spite fence presses as close to its target building as property boundaries will allow, ideally fitting roof-high against it as snugly as the side of a packing crate.

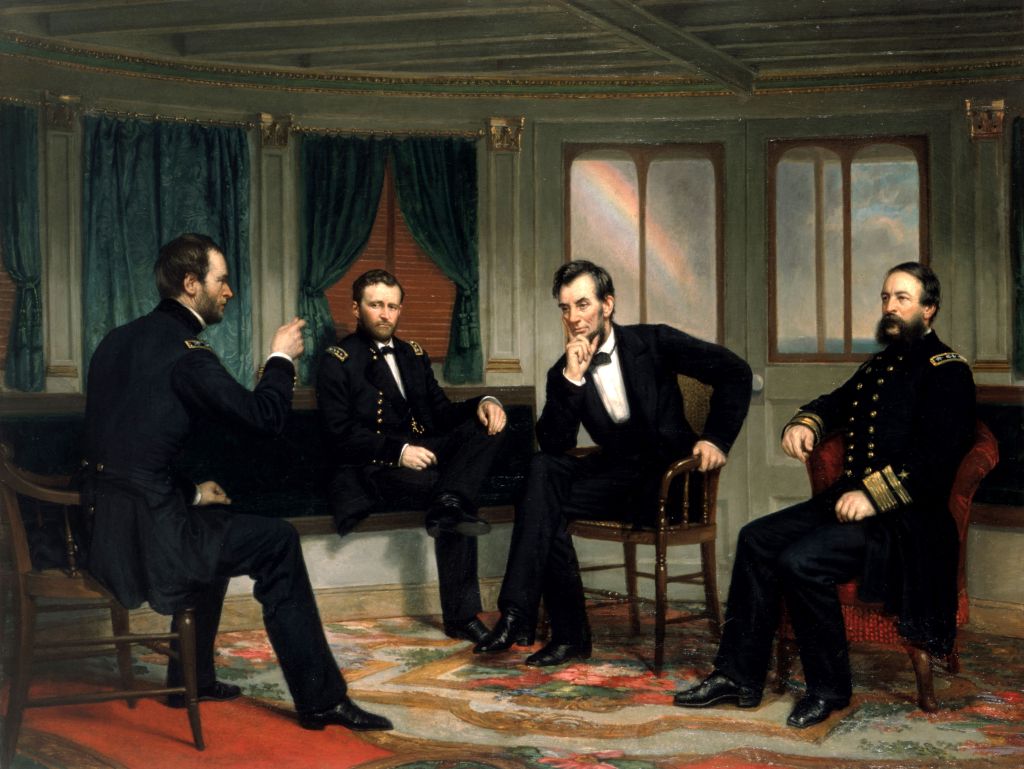

From the moment he was first inspired to paint it, George Peter Alexander Healy harbored huge ambitions for the canvas he entitled The Peacemakers. The artist longed for it to be universally embraced as “a true historical picture,” cherished as the emblem of sectional reconciliation following the Civil War.

It was not to be. At least not until now, thanks to an unexpected renaissance in its reputation, one inspired by another president, another artist, and another painting. It may sound unfathomable, but credit George Bush with thus giving Abraham Lincoln an image boost this year.

I love America. I wonder how many Englishmen can say that. Most of us know it too little to feel strong emotion one way or the other. New York, Washington, San Francisco, Los Angeles, the Florida holiday resorts—that is the America of most English people. My America is larger altogether. I have visited, for reasons that will emerge, thirty-two of the fifty states and most of Canada as well, and I have been making those visits for nearly forty years. In an idle moment I counted up not long ago the number of U.S. Immigration Service entry stamps in my passports and found nearly fifty. “Boston,” the first one says, in a passport from which a schoolboy face stares back at me.