Blazoned in huge black letters across page one of the December 4, 1941, issue of the Chicago Tribune was the headline: F.D.R.’S WAR PLANS! The Times Herald, the Tribune ’s Washington, D.C., ally, carried a similarly fevered banner. In both papers Chesly Manly, the Tribune's Washington correspondent, revealed what President Franklin D. Roosevelt had repeatedly denied: that he was planning to lead the United States into war against Germany. The source of the reporter’s information was no less than a verbatim copy of Rainbow Five, the top-secret war plan drawn up at FDR’s order by the Joint Board of the Army and Navy.

January 2011

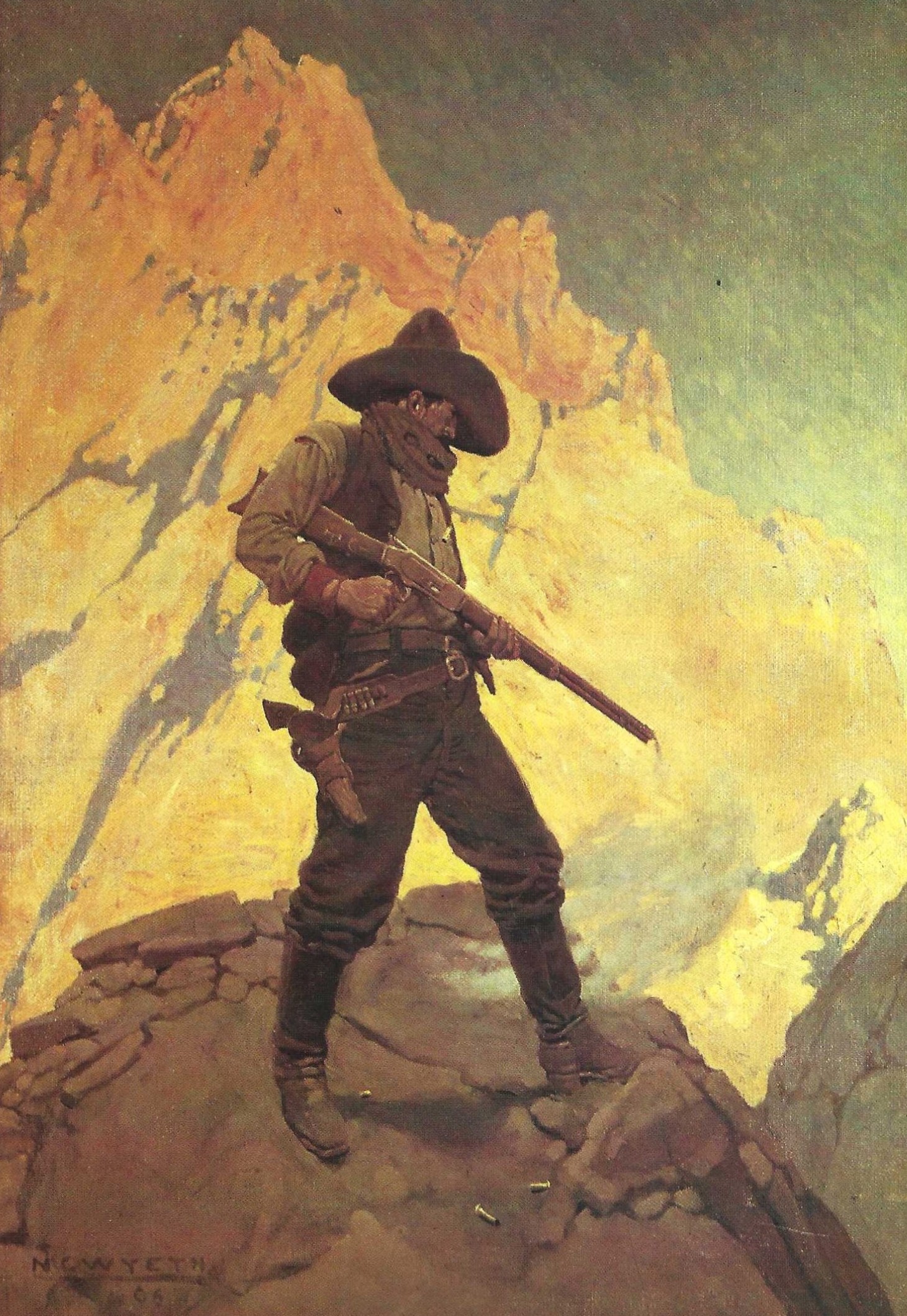

Each of the twelve months that rolled past since the last Winter Art Show has brought its freight of marvelous pictures to our editorial offices. Many we put in the magazine; many more we could not, and of these we have again selected some favorites. As with our earlier art shows, each of the pictures has something to reveal about the American past—whether it be the feel of the suburban dusk in Indianapolis fifty years ago, or the still, waiting hours before the mortal work began at Gettysburg.

The arresting portrait at left is by an artist with impressive ancestry—Ellen Day Hale, descendant of Nathan Hale, daughter of Edward Everett Hale, and great-niece of Harriet Beecher Stowe. Born in Boston in 1855, Ellen Hale studied art there and in Paris, becoming known for her vivid colors and powerful execution. After 1904 she moved to Washington, D.C., where she sketched President Theodore Roosevelt. This confident young woman holding an ostrich fan is the artist herself, at age thirty.

In 1892, when the statesman John Hay was building his house in Washington, D.C., he commissioned a pair of stained-glass windows from the artist John La Farge. Although he was quickly overshadowed by Tiffany, La Farge was America’s greatest innovator in the medium: the first to use opalescent glass and the first to translate flat Japanese design into windows. For the Hay House, La Farge created a peacock window and one of windblown peonies. His watercolor sketch for the peonies shown here is even lovelier than the final version.

Alson Skinner Clark was born in Chicago in 1876, and studied in New York under William Merritt Chase, some of whose easy authority he brought to this study. We don’t know to whom this immaculate house belonged, but the sheen on the floor suggests the presence of many servants—which is also borne out by the date, 1915. A few more months, and America will be in the war that began the process by which many such scenes of gleaming tranquillity were dispelled forever.

Thomas Worthington Whittredge was a member of the Hudson River school known for his affection for what he called “homely scenery.” After studying in Europe, he did most of his painting in the East, particularly the Catskills. But beginning in 1866, Whittredge made three trips to the West. His Wagon Train on the Plains, Platte River , above, its subject overwhelmed by the vast empty spaces, is as eloquent in its way as the mountains of his contemporary Albert Bierstadt.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper reported on December 6 that all the ailanthus trees on the nation’s Capitol grounds were being uprooted and carted off. “The odor had become so offensive,” Leslie’s explained, “that the removal was necessary.

On December 12 Japanese bombers sank the clearly marked U.S. gunboat Panay and three Standard Oil supply ships in China’s Yangtze River, killing two Americans and wounding thirty. At the time, Japan was at war with China, and the American vessels were on the Yangtze to evacuate American officials. The news of the sinkings angered Americans, and Secretary of State Cordell Hull demanded redress. The incident ended when Japan apologized, promised full indemnity, and agreed to punish those responsible.

Being a Westerner is not simple. If you live, say, in Los Angeles, you live in the second-largest city in the nation, urban as far as the eye can see in every direction except west. There is (or was in 1980—the chances would be somewhat greater now) a 6.9 percent chance that you are Asian, a 16.9 percent chance that you are black, and a 27 percent chance that you are Hispanic. You have only a 48 percent chance of being a non-Hispanic white.