Throughout his working life, Thomas Easterly’s St. Louis acquaintances knew him as “the daguerrean,” a title that reflected the man’s stubborn espousal of the first photographic method known in America. Long after his colleagues had adopted newer techniques, Easterly stuck by his belief in its superior qualities. “Save your old Daguerreotypes,” he urged, “for you may never see their like again. … By no other process can so perfect and durable a likeness be produced and every unprejudiced artist will bear testimony to what we assert.”

January 2011

During November of 1896 the United States experienced its first publicized UFO flap, and it is perhaps not surprising that it should have occurred in California. After all, Erich von Däniken would have us believe that the prehistoric petroglyphs in Inyo County represent interplanetary flight; Fray Geronimo Boscana, the missionary at San Juan Capistrano, described a “two-tailed comet” overhead in 1823; and in 1883 the scientist John J. Montgomery began his heavier-than-air experiments by putting a glider into the air over the sun-browned hills of Otay Mesa, south of San Diego.

All this, though, was pretty small change compared with the arrival of “The Great Airship.”

Human beings have been traveling in circles for an astonishingly long time. In A Pictorial History of the Carousel , Frederick Fried tells us that a Byzantine bas-relief of about A.D. 500 depicts people swinging about a center pole in baskets, and by the middle of the eighteenth century, a lot of going around was going around in Europe, as people dizzied themselves on everything from simple man-powered merry-go-rounds to elaborate handcrafted carousels whose motive power was equine.

“There is in the western country a very extraordinary missionary of the New Jerusalem. A man has appeared who seems to be almost independent of corporal wants and sufferings. He goes barefooted, can sleep anywhere, in house or out of house, and live upon the coarsest and most scanty fare. He has actually thawed the ice with his bare feet.

“He procures what books he can of the New Church; travels into the remote settlements, and lends them wherever he can find readers, and sometimes divides a book into two or three parts for more extensive distribution and usefulness.

“This man for years past has been in the employment of bringing into cultivation, in numberless places in the wilderness, small patches (two or three acres) of ground, and then sowing apple seeds and rearing nurseries.…”

Americans are a counting nation. They like figureslarge figures such as the gross national product, industrial production, consumer spending, consumption of energy, even measures of economic activity in such arcane areas as the production of brooms, brushes, and pickles. Especially do our people like to count themselves. This has been going on for a long time, serially in every year ending in zero since 1790. There is more to this than a mere quirk of national character. Statistics as an instrument for ensuring political equality are imbedded in the United States Constitution, which requires that political power be apportioned according to population. That is the primary historical and legal reason why we count ourselves every decade with a margin of error that has been thinned down to 2.5 per cent and is expected to fall still lower in 1980.

After reading an interview with General Gavin in a newspaper, a major who had fought in the Huertgen Forest wrote the general the following letter:

December 26, 1978

Dear General Gavin ,

… I was S-3, 2nd. Bn. 121 Inf., 8th. Div., and my outfit was the only one to secure the village of Huertgen, and hold on to it .

On a windy day on North Carolina ‘s Outer Banks, seventy-six years ago this month, two men in business suits coaxed the first powered aircraft into the sky, controlled it for a perilous 59 seconds, and changed the world we live in. Wilbur and Orville Wright ‘s breakthrough is here recounted by a veteran airman, Harry Combs—who first soloed in an open cockpit biplane when he was fifteen—with the novelist and aviation historian Martin Caidin. The article is excerpted from their forthcoming book, Kill Devil Hill: Discovering the Secret of the Wright Brothers , to be published by Houghton Mifflin in December. Our story opens when the Wright brothers, having worked all year on a new flying machine, return to their sandy island testing site in the fall of 1903.

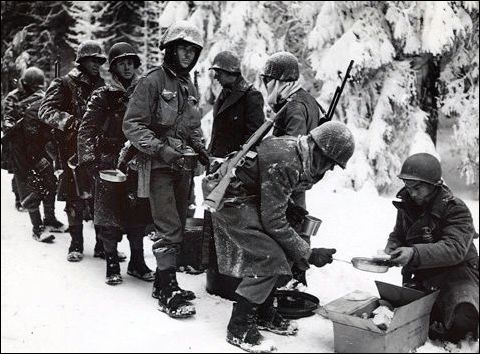

The Battle of the Bulge came to an end in the closing days of January, 1945. The combat divisions were immediately redeployed to resume the offensive into Germany, and the 82nd Airborne, which I commanded, was ordered into the Huertgen Forest, a densely wooded area astride the Siegfried Line, just inside the German border. In the fall of 1944 there had been many grim stories in the Stars and Stripes , the army newspaper, about the fighting in the Huertgen. We were not looking forward to the assignment.

Eight million words. Seventeen thousand pages. Fifteen thousand illustrations. Six linear feet. One hundred and seventy-eight pounds. …

The statistics are daunting. Marshaled together, the one hundred and fifty hardcover volumes of AMERICAN HERITAGE now outstretch by thirteen inches Dr. Eliot’s celebrated five-foot shelf. They contain more than sixteen hundred articles. Some are about titanic achievements and tragic struggles, some about lost minor arts. But all are about our history.

“We are the nation’s memory.” Oliver Jensen has written of the magazine he helped create a quarter of a century ago this month. A national memory is a lot like a human memory; is, in fact, made up of the same mixture of the vast and the trivial. Some events stand out in high relief—illuminated, say, by the fierce blaze of an artillery barrage or the flickering of a torchlight parade—while most are quieter: the trip to the beach in the old Hudson; sledding in the side yard under a cold, bright sky; the early morning jostle of milk bottles being delivered.