At one point in the sad, oddly bland autobiography he wrote in his prison cell, Charles Chapin recalls fondly the reporters who served under him when he was city editor of the New York World: Barton Currie, Will Inglis, Cupid Jordan, Jimmy Loughboro, Joe Brady—”and a lot of other bright chaps, for whom I have always felt a deeper affection than they perhaps credited me with.” That circumspect remark is the only indication he gives that all those men hated his guts. They worked for him because he paid them top salaries, and because he ran the city desk of the best newspaper in America. But they hated him all the same. “I never saw or spoke to a member of the staff outside the office. …” he wrote. “I gave no confidences, I invited none. I was myself a machine, and the men I worked with were cogs.”

Every December 21, Farmington, Maine, erupts into its annual winter festivities in hectic observance of Chester Greenwood Day. At the age of fifteen, Chester Greenwood (18581937), a local boy, fashioned a pair of muffs to protect his ears from the cold while skating. He later perfected the design, and at nineteen received a patent for what he insisted on calling Greenwood Ear Protectors. Whatever he chose to call them, what Greenwood had done was to invent earmuffs, and for more than sixty years he made it his business to manufacture and sell them.

Some observant Anglophiles have Owritten in to take issue with one of the captions that accompanied “When Does This Place Get to New York?” in our June/July, 1979, issue. That caption identified “Queen Mary herself” on page 87 visiting the Queen Mary . Not so, these readers point out. The visitor in question (see photo at right) is in fact the then Queen Elizabeth, consort of King George VI, and the mother of today’s Queen Elizabeth II.

In our June/July, 1978, issue we ran a short article having to do with Mark Twain’s invention of a “self-pasting” scrapbook, then followed it up with a “Postscripts” feature in the February/March, 1979, issue that emphasized Twain’s willingness to write promotional letters for the use of the scrapbook’s manufacturer, the Slote & Woodman Company. Now, Robert Daley of the Burbank Studios of California sends along yet another promotional squib put out by the author of Huckleberry Finn : Certificate Messrs. Slote, Woodman & Co.:

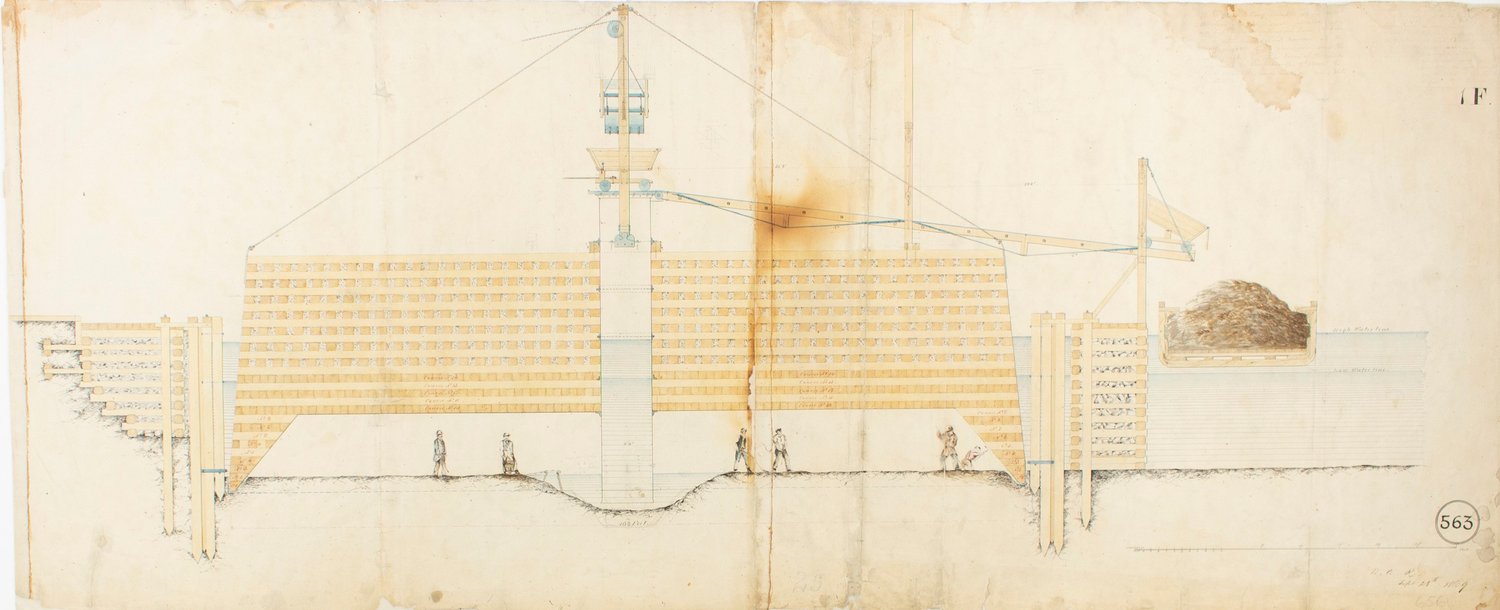

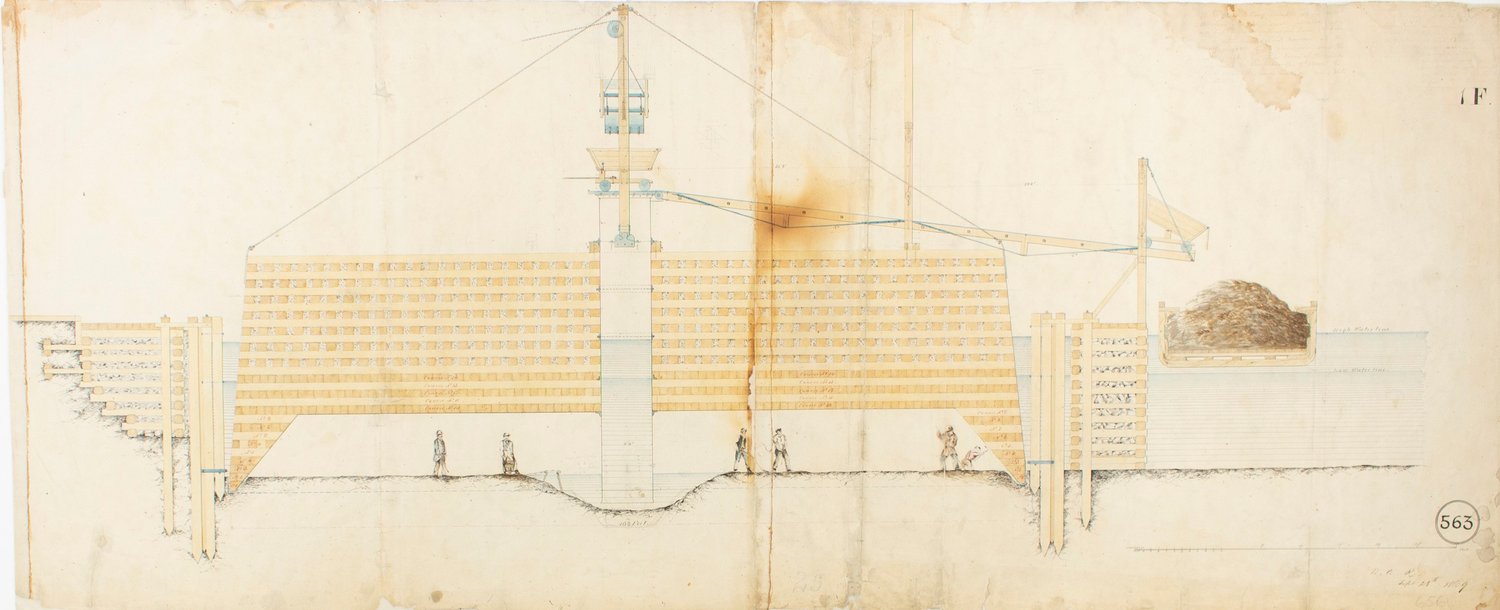

The excursion steamer Eastland was known as “the crank ship of the Lakes” to the men who worked her. Built for speed—she had to make the 170-mile round trip between Chicago and Grand Harbor, Michigan, twice a day—she had a lean, graceful hull and tall, heavy superstructure. On July 24, 1915, after twenty-five hundred people had crowded aboard, she capsized at her dock in the Chicago River. Eight hundred and thirty-five died.

Among those who witnessed the tragedy was Mrs. Eva L. Burchill of San Jose, California, who sent us this picture of the deadly ship on her port side, and this reminiscence:

“When I saw the boat it was lying on its side. The river was crowded with small boats and people were being plucked from the water. I saw this from an elevated train crossing the river bridge.

Since 1913, U.S. Capitol antiquarians have had a small embarrassment on their hands. It was in that year that a handsome bronze bust was discovered squirreled away in a room under the Capitol building’s crypt in Washington, D.C. You don’t throw something like that away, obviously, even if you have no place to keep it; even, in fact, if you don’t know who the bust is supposed to represent. And so far, no one does, though, as the New York Times reported on July 17,1979, “hundreds of people have studied it, some becoming convinced it was of Thomas Jefferson, Hans Christian Anderson, Abner Doubleday, or even George Washington.” Well, there it sits, on top of a filing cabinet in room HB28 of the Capitol building, under the watchful eye of researcher Florian Thayn. If any of our readers can provide clues, we will be happy to pass them along.

by Cassie Brown

Doubleday & Co. Charts, photographs, and sketches by a survivor 391 pages, $12.95

On the night of February 18,1942, two hundred and three young American sailors drowned, suffocated in oil, were battered to death on rocks, or died of exposure in one of the worst—and least publicized—disasters in U.S. naval history. No enemy action was involved. Three vessels, the destroyers U.S.S. Wilkes and U.S.S. Truxtun and the supply ship U.S.S. Pollux , ran aground in a storm on the south coast of Newfoundland. There were one hundred and eighty-five survivors, and they owed their lives to the extraordinary gallantry of the people who lived in two small nearby villages.