A number of readers have written us to celebrate the fact that we have lately taken to running our articles all in a piece, rather than “jumping” them to the back of the issue. Apparently many people appreciate not being forced to rummage around in the lost-and-found region of the back pages, and we plan to continue this new policy whenever possible.

January 2011

The cover of our February, 1977, issue inspired, amoner others, the following letter from the Honorable Thomas F. Butt, probate judge of the Thirteenth Chancery Court of the State of Arkansas: “Surely, surely, your make-up staff reversed the negative on the reproduction photo of Speaker Joe Cannon. Surely ‘Uncle Joe’ was not left-handed; surely, the national flag behind the speaker was not incorrectly hung, in actuality. Properly hung, the starred union of the flag should be at its upper right quarter rather than in the upper left quarter as shown in the photo. I suspect this letter will be about the 4,004th such communication inviting your attention to this apparent error.”

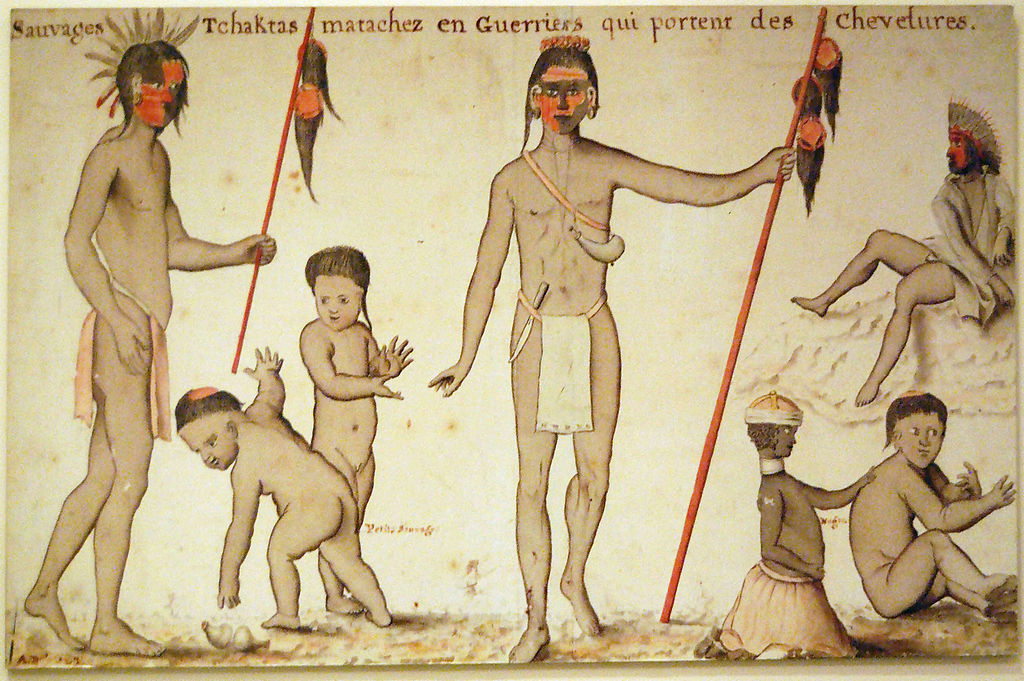

In “Who Invented Scalping?” an article in our April, 1977. issue, James Axtell argued that—contrary to recent revisionist notions—Europeans did not teach the Indians how to scalp. The Indians, he said, had learned it all by themselves and had practiced it long before Europeans inflicted themselves on this innocent continent. Additional evidence to support Mr. Axtell’s theory has since come to us from Douglas Owsley and Hugh Berryman, anthropologists at the University of Tennessee, who furnished us with the photograph above and a description of what happened to the skull’s former owner:

“The human skull shown in the picture is that of an adult male American Indian who was scalped. The bones of this individual [who died in about A.D. 1300] were recovered during an archaeological excavation of the Arnold site in Williamson County, Tennessee. … Cuts in the bone (visible in the photograph) extend across the forehead in the approximate location of the hairline. Two or three strokes with a sharp stone knife were all that was required.

The idea of urban renewal has traditionally been predicated on the superficially reasonable assumption that the best way to handle crumbling blight is to pluck it out—raze it, tear it down, get rid of it—and build something better: shopping malls and office complexes, say, or apartments and town houses, civic centers and sports arenas.

Abraham Lincoln is generally considered to have been the best writer of all our Presidents. But like any other writer, it took him a while to get there. As an example, we offer the following excerpt from remarks he delivered to the Illinois House of Representatives on December 26, 1839, a speech that derived its emotional character from the dire conviction that Van Buren Democrats might ultimately bring ruin to the Republic. In his conclusion, the thirty-year-old Whig became nearly unhinged:

Abraham Lincoln is generally considered to have been the best writer of all our Presidents. But like any other writer, it took him a while to get there. As an example, we offer the following excerpt from remarks he delivered to the Illinois House of Representatives on December 26, 1839, a speech that derived its emotional character from the dire conviction that Van Buren Democrats might ultimately bring ruin to the Republic. In his conclusion, the thirty-year-old Whig became nearly unhinged:

Samuel Thomson’s course of treatment was benign compared to the calomel-and-bleeding methods prescribed by regular physicians. But it, too, could be overdone, as it clearly was in the case of one Jona Sherburn of East Randolph, Vermont, a sufferer from rheumatism. In the summer of 1841 Sherburn took his pains to Dr. Jehiel Smith, founder and proprietor of the Thomsonian Infirmary and Insane Asylum. Dr. Smith claimed he could cure apoplexy, epilepsy, vertigo, cholera, smallpox and chicken pox, rabies, gout, leprosy, venereal diseases, diabetes, cancer, and rheumatism—to name just a few ailments. Apparently patient Sherburn did not know of the dubious reputation Dr. Smith had already earned in Strafford, Vermont, twenty miles away. Dr. Smith had left there in 1836—precisely why, no one knows. But before he departed, friends had found it necessary to write testimonials to his character and to attest that they believed “all the evil reports in circulation about him to be entirely false.”

Americans have always assumed that scalping and Indians were synonymous. Cutting the crown of hair from a fallen adversary has traditionally been viewed as an ancient Indian custom, performed to obtain tangible proof of the warrior’s valor. But in recent years many voices—Indian and white—have seriously questioned whether the Indians did in fact invent scalping. The latest suggestion is that the white colonists, in establishing bounties for enemy hair, introduced scalping to Indian allies innocent of the practice.

If the orange was the tangible, edible symbol of all that California was supposed to be, then the single most ubiquitous and effective means ever devised by the citrus growers of the state to get their message across was the label pasted on the sides if wooden crates that swelled with packed fruit. In such labels, industry, art, and symbol became one, and on these and the following pages we offer a definitive selection. From the beginning, the California citrus-crate label defied all attempts at taking it too seriously. It was an art form as inadvertent as it was handsome, and had about it an insouciant confidence, an agreeable sassiness, that made it seem content to remain just what it was: uncomplicated, forward, and cheerful.