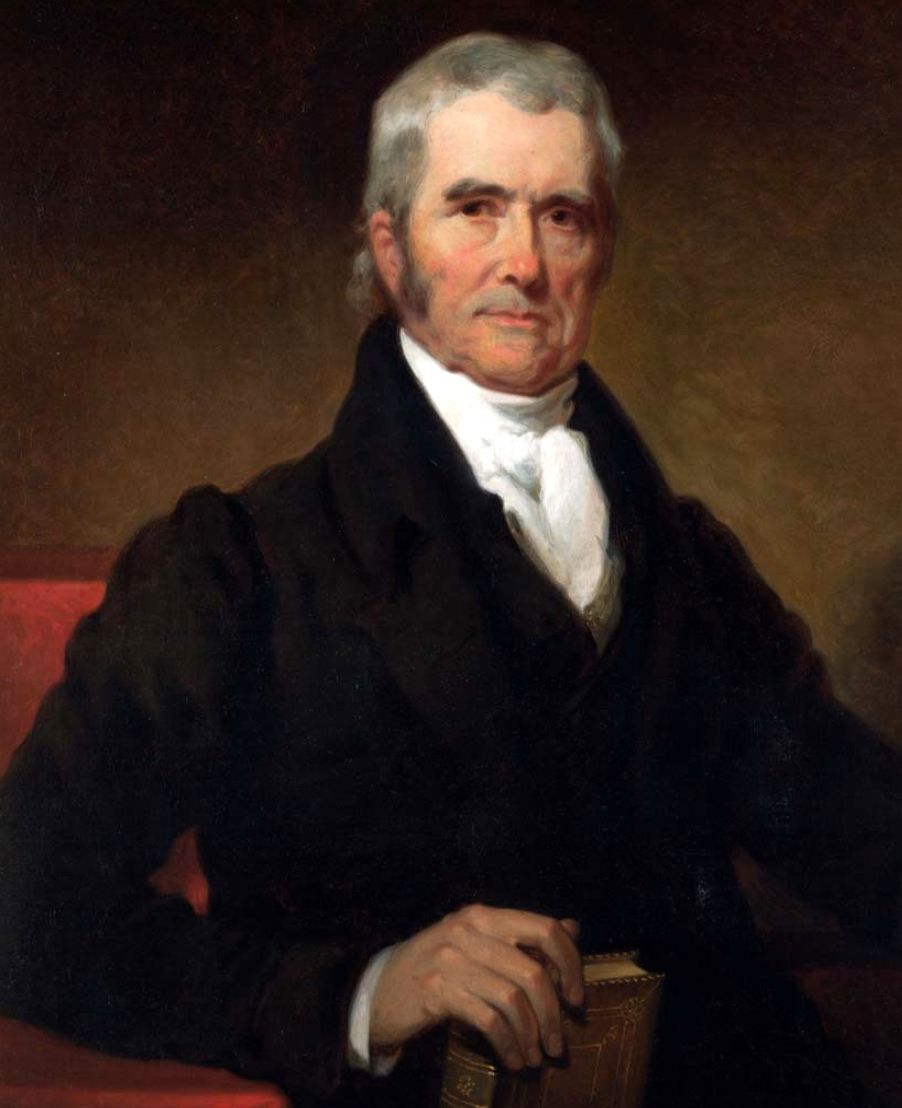

On the grounds of the Ewa Plantation School just west of Honolulu stands a bronze statue of a young Abraham Lincoln with ax in hand, forearms rippling after splitting logs. Fifteen years before Hawaii became a state in 1959, school officials unveiled this statue, a symbol of Lincoln’s popularity in Hawaii during the American Civil War, when many Hawaiians enlisted in the Union Army and Navy despite the kingdom’s official neutrality.

Strong anti-slavery sentiment motivated some to serve in African American military units, supporting the Union cause against the seceding slave-holding South. These views, plus Lincoln’s personal relationship with Hawaiian ruler, King Kamehameha IV, strengthened Hawaiians’ affection for the American president.

In 1865, shortly after Lincoln’s assassination, the Honolulu newspaper Ka Nupepa Kuokoa expressed the sorrow of the Hawaiian people at the death of what it called the “people’s friend.” It argued that “no parallel for this great crime can be found in the world’s history since the Crucifixion.”

On this Lincoln’s birthday, as in years past, Ewa’s students will wreathe the statue in leis.