January 2011

After six months of war, a parade or demonstration barely ruffled the surface of downtown Barcelona. Whenever bands and crowds occupied the Plaza de Cataluna and lightly shook the surrounding buildings with anthems and vivas , only a few clerks at the United States consulate abandoned their desks for the windows. The reason for these disturbances was ever the same: the volunteers of the International Brigades were arriving from France, or Catalan troops were departing for the front. But on January 6, 1937, Mahlon F. Perking the consul general, who watched the crowd teeming below, spotted an object that had never before appeared in the marches and rallies. Coming up the street was the flag of the United States. Behind it ambled sixty men in 1918 doughboy uniforms. They were lined up in four-front squads with their leader out in front, a .45 automatic strapped to his hip. The United States Army in Barcelona? Impossible!

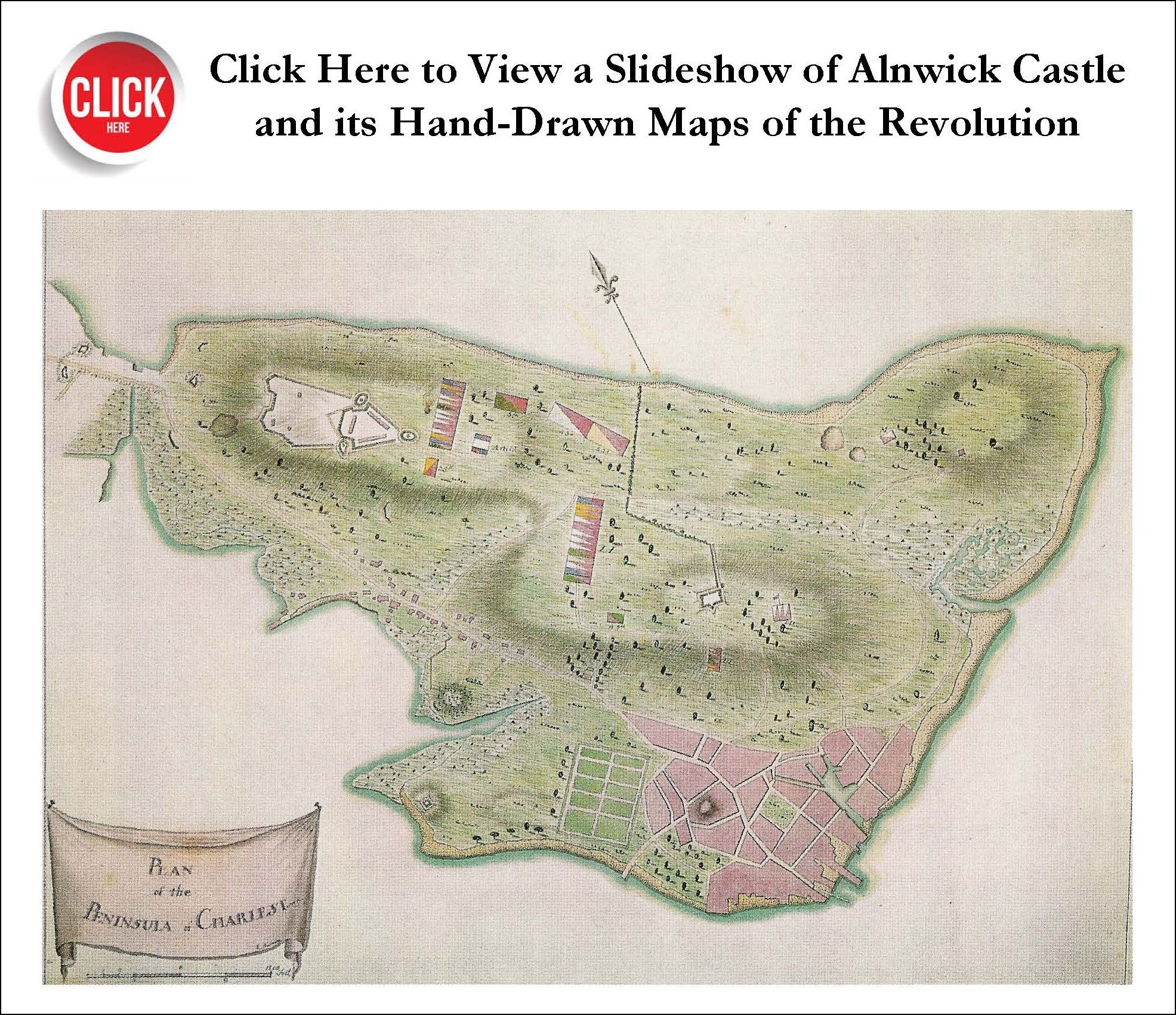

The maps which the authors of the accompanying article discovered in Alnwick Castle have been there, almost untouched, ever since 1777, when Earl Percy brought them back from his tour of duty in America. It is extraordinary to find in one place such a large number—over fifty—of Revolutionary War maps covering many major battles and drawn soon after the events by the best British military cartographers of the time. The present Duke of Northumberland- seen at right in his library with a few of the maps—has a lively appreciation of family history: he has visited the United States and walked over some of the ground his distinguished ancestor fought upon, and he has had Earl Percy’s maps properly catalogued at last. With his kind permission A MERICAN H ERITAGE reproduces for the first time, on the next six pages, some of the most notable treasures of the collection.

These are rare publicity stills from some of the most important films ever. made. The films are significant either because they were the creations of great directors and writers, or because they featured memorable acton and actresses. But never again will these flickering images be projected upon the silver screen. Why not? For the answer, turn to page 34.

We stood beside the billiard table in a richly beautiful room in Alnwick Castle, hesitating for a moment before opening the great portfolio which the Duke of Northumberland had laid out for us. On the walls shone the mellow beauty of Titians and Tintorettos. Outside the high windows the great park rolled upward to the hills of the border country. The Duke spoke encouragingly. “My ancestor was one of the commanders of the British troops in Boston in 1775,” he said. “He liked maps. His collection has been here in a black box ever since he came home, until I put it into this portfolio. Do you care to look at it?”

We stood beside the billiard table in a richly beautiful room in Alnwick Castle, hesitating for a moment before opening the great portfolio which the Duke of Northumberland had laid out for us. On the walls shone the mellow beauty of Titians and Tintorettos. Outside the high windows the great park rolled upward to the hills of the border country. The Duke spoke encouragingly. “My ancestor was one of the commanders of the British troops in Boston in 1775,” he said. “He liked maps. His collection has been here in a black box ever since he came home, until I put it into this portfolio. Do you care to look at it?”A favorite story on Long Island concerns a man at Westhampton Beach who received in the mail on September 21, 1938, a barometer purchased a few days earlier in New York. He found the instrument’s needle pointing down near 28 degrees, at the section of the dial marked “Tornadoes and Hurricanes.” He shook the barometer and banged it with his fist, but the needle refused to move, so he rewrapped it, enclosed a note of complaint, and carried it to the village post office. Soon after he mailed it, his shorefront house was demolished—by hurricane.

It is unlikely that such a barometric warning would be disregarded today on Long Island or along the New England coast, where there have been several hurricanes since 1938. But in that year such storms were almost unknown in the Northeast, and the Weather Bureau didn’t bother much about tracking coastal disturbances north of Virginia, assuming that storms moving up from the Caribbean would blow out to sea at Cape Hatteras, as most of them indeed do.

The Mississippi River w;is W both boon and bane to midnineteenth-century St. Louis. It was an obvious blessing as a trade thoroughfare to the sea; but the same Mississippi, broad and deep—and unbridged—was keeping vital east-west rail traffic from the city. St. Louis businessmen fumed as Chicago’s industrial boom was abetted by several river-spanning bridges in northern Illinois. St. Louis needed a bridge and would have to choose its architect with great care.

Astonishingly, St. Louis turned to a man who had never in his life built a bridge; in fact he had never been formally trained as an engineer, although he was famous for his engineering feats. The self-taught genius was James Buchanan Eads, and his career up to the time when he undertook the great St. Louis bridge was already an amazing American success story.