How George Washington Designed the Cabinet as the Most Important Governing Tool

No president ever leads alone. Moments of crisis tend to emphasize the people surrounding the president and offering support or guidance.

Cabinet officials should be the president's most important advisors. Ideally, they bring diverse perspectives, experiences, and expertise that inform decisions in moments of chaos. In fact, President George Washington created the cabinet to provide support when faced with constitutional dilemmas, domestic insurrections, and international crises. The cabinet precedents he established have largely guided his successors, and they determine whether a president is remembered by history as a success or failure.

You won’t find the word "cabinet" in the Constitution. The founding document did not create the cabinet, nor did any legislation form the institution. In fact, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention explicitly rejected several proposals for a cabinet.

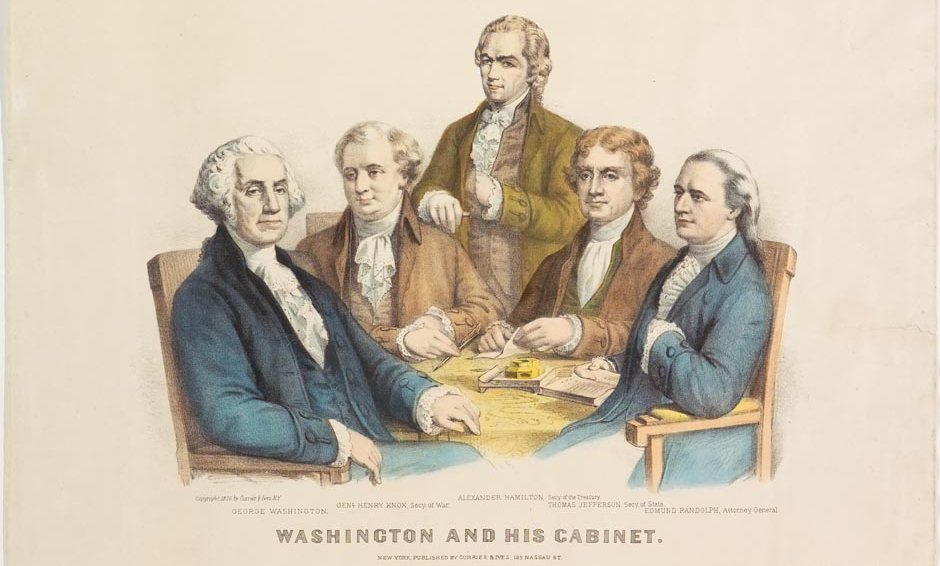

After his inauguration, Washington initially followed the options outlined in Article II, Section 2, but he quickly discovered that they were insufficient to burdens of governing and explored other alternatives. On November 26, 1791, two-and-a-half-years into his presidency, Washington convened the first cabinet meeting. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of War Henry Knox, and Attorney General Edmund Randolph gathered in Washington’s private study in the President’s House on Sixth and Market Streets in Philadelphia to discuss possible treaties with France and Great Britain.

[See also George Washington Invents the Presidency,

by Joseph J. Ellis in the Winter 2020 issue]

Washington selected these secretaries, and their eventual successors, very carefully. He weighed three criteria. First, like all presidents, he wanted a personal relationship with them. It’s hard to take someone’s advice when you don’t know or trust them.

Second, he wanted secretaries that had expertise, knowledge, and experience that were different than his own. Washington intended to ask for their advice and follow it — they needed to know what they were talking about. For example, Jefferson had extensive diplomatic experience, while Washington had only left the country once to go to Barbados as a teenager. Similarly, Randolph had legal training and practice, and was widely regarded as one of the top legal minds in the country. Washington had little formal schooling and depended on Randolph’s constitutional interpretations.

Washington selected cabinet secretaries that would encourage other citizens to emotionally invest in the new nation.

Third, Washington used cabinet appointments to represent the different geographical and regional interests in the new nation. When Washington took office in 1789, the states were barely held together by tenuous economic and legal bonds. He selected secretaries that would encourage other citizens to emotionally invest in the new nation. Jefferson stood for the southern, elite plantation owners who owned hundreds of enslaved individuals. Hamilton spoke for the northern, urban mercantile merchants and traders.

Since then, presidents have generally followed this example. They have also expanded who deserves representation in the cabinet to include people of different races, genders, religions, cultures, and more.

While some turnover is to be expected, Washington and his successors sought to provide as much continuity, stability, and institutional knowledge as possible. John Adams even went so far as to keep Washington’s secretaries in office for the first few years of his presidency. While Adams struggled to control Washington’s secretaries, other presidents have had more success with this model. President Franklin D. Roosevelt managed the American war effort with Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Secretary of Navy Frank Knox—both Republicans that had served in the Taft and Hoover administrations. Jefferson had the least cabinet turnover in history.

The cabinet secretaries serve as some of the most visible public representatives of the president and the executive branch. Their successes bring acclaim and their failures or scandals tarnish the president’s reputation. Accordingly, Washington distanced himself from scandal whenever possible. In 1795, he dismissed Edmund Randolph after Secretary of Treasury Oliver Wolcott, Jr. and Secretary of War Timothy Pickering accused him of selling state secrets to the French.

While these accusations were based on faulty information, Washington barely gave Randolph an opportunity to defend himself. Instead, he ended a decades-long relationship, prioritized the reputation of the government, and ensured he could not be accused of favoritism toward his former friend.

Washington’s successors have generally followed his lead and with good reason. An effective cabinet seamlessly helps the president pursue his or her agenda, while a problematic cabinet can imperil an administration.

Lindsay M. Chervinsky, Ph.D. is a historian and author of The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution (Harvard University Press, 2020). She is on Twitter @lmchervinsky.