An astonishing saga of endurance and high courage told by a man who lived through it

-

February 1988

Volume39Issue1

Editor's Note: This is a true story of a boy and his family living on the high prairie in an adobe house in eastern Colorado and the tragic events that occurred in March 1931. This essay by E.N. Coons of his recollections of the snowstorm won a Western Heritage Award from the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in 1989 for outstanding magazine article of the year.

A good dobe house was something to be proud of, warm in winter and cool in summer, with walls sixteen inches thick. We had just built ours. We plowed up a strip of prairie soil about fifty feet wide by 200 feet long and twelve inches deep. Then we put in water enough to make a mudhole and rode horses back and forth until the dirt was sloppy. We added to that slop two or three wagonloads of wheat straw, then took six or eight horses and walked them back and forth until the straw and mud were mixed real good. Then we built molds of boards and shoveled the mud straw mix in, and when the mud dried we had big dobe blocks two feet long, sixteen inches wide, and six inches thick. The wind and hot sun baked them hard as bricks. Then we laid the big blocks of dobe in place with more mud, and after the house had settled and dried out, we plastered the walls with lime and sand, making a smooth surface inside, then painted it with lime, water, and color mix. Now this was our home where this story all began.

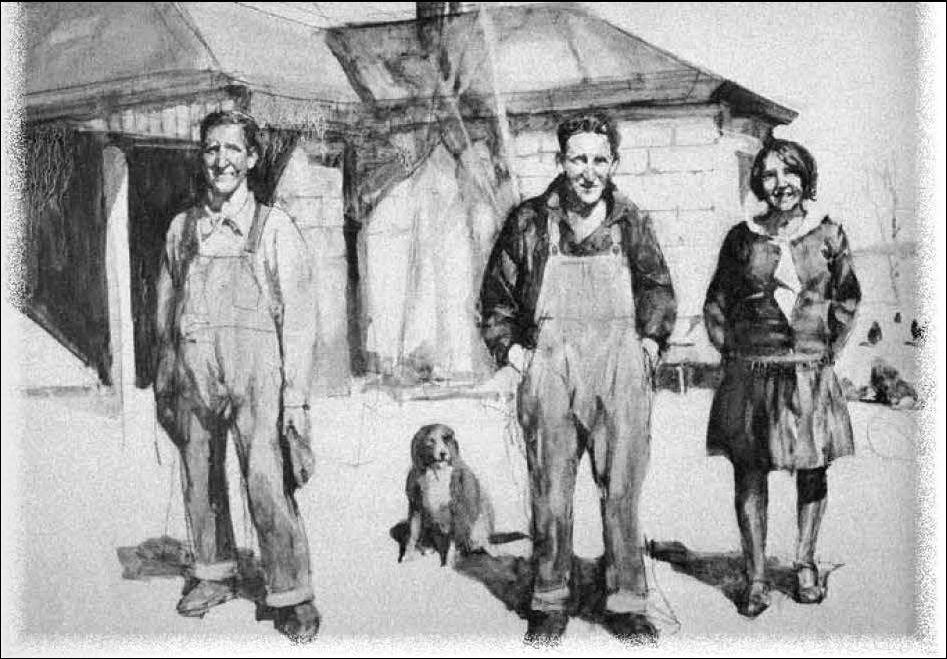

The family consisted of Dad, born 1885, who was a pioneer of the Old West and very rugged; Mama; and three children: Edna, twenty; Ethel, fourteen; and myself, Elbern, eighteen.

On the morning of March 28, about 6:00 A.M. in 1931, Mama got up early as usual and told us all to get up. We didn’t want to because we had worked hard the day before getting some ground ready for the garden and cutting out the milk cows from the range cattle so we could turn them out onto the range, for feed was running short; but we all climbed out of bed. It had been cold, but now it was like spring; there was a soft breeze from the south with a fine mist. You could stand out in that mist, throw your chest out, and say, “Boy, at last winter is over.” You could hear birds singing. It was about sixty-five degrees, and what a beautiful morning!

Ethel, Dad, and I went out to the barn and did all the chores. We were milking about 15 cows by hand, but it didn’t take too long, about an hour. We brought the milk to the house and ran it through the cream separator. By that time Mama had breakfast ready.

Mama was a good cook, if I do say it. We had rabbit sausage, whole-wheat pancakes, and homemade syrup. Mama was talking in the Czech language — her folks came from Czechoslovakia — saying, “You better get down to the table and fill your gut, for we have a long day ahead.” She did not know then just how long it really was going to be. So we all sat at the table, and Dad and Mama decided maybe Dad and I should go to Lamar, about sixty miles, and get seed and supplies for spring planting.

Dad said, “Kids, we are going to have an early spring and a good year this year.” We were all in high spirits. Going shopping was going to be quite a treat, for it had been four or five months since our last shopping trip. So I hurried around and got the car ready, filling the tank with gas out of a barrel.

All at once, Mama said, “It’s getting colder.” We looked out at the thermometer, which was kept hanging on the wall just outside of the door, and sure enough, the temperature had started to drop. We did not have a radio, but we all knew something was coming, for the cows in the corral were milling around and seemed to be getting restless, and that meant a change in the weather.

Now it’s about 8:00 A.M. on the 28th. Edna was teaching a small country school about one and one-half miles northwest of our farm, and Mama told her to dress extra warm. I heard her say, “It might get bad.” Ethel was a pupil at the same school, but Mama said, “You’d better stay home with me today, for if it was to turn bad, I would be alone with all these chores to do.” So Ethel stayed home. Mama must have known something was going to happen.

Dad said, “We better get started and get back before it turns too bad.” Even though we had our woolen underwear on and I was about to roast, Dad said, “Brother, let’s take our overshoes, our felt boots, and sheepskin coats.” (The family always called me “Brother.”) Mama packed our lunch in a big flour sack. She also put in two extra pairs of homemade mittens and our pullover masks. As we got in the car, the soft breeze from the south had stopped, and it was calm as could be. This was a bad sign, since a bad blizzard is much like a tornado, with the calm just before the storm.

We went about 20 miles, and suddenly I began to get cold. By this time it had started to snow. I looked back and I could see a big ugly black cloud coming from the north. “Maybe we better turn back,” I told Dad, but he said, “No, we better go on, for it probably will blow over in a couple of hours.” I was getting colder by the minute, and it had started to snow faster. We went on, and as we entered Lamar, the temperature had reached thirty below zero. Lamar is only about three thousand feet elevation, and our farm is about four thousand feet. So, we were not feeling the impact of what was happening at home, for we lived on the upland prairie and Lamar is on the Arkansas River.

We ate our lunch, which was about frozen, and wondered how Edna, my sister, was going to get home from school afoot.

We loaded up our car with seeds and some dried fruit that came in 25-pound boxes — dried apples, raisins, prunes, and figs. We didn’t buy meat, for we had beef, goat, and jackrabbit. But we left behind a lot Mom had ordered. While at the store Dad looked out and said, “Look at that snow!” While Dad was looking at that snow, somehow my girl friend popped into my mind, I didn’t know why. We had gone to a Charlie Chaplin movie a couple of days before, but for some reason I kept thinking about her (later I found out why), but then I looked out and it was blowing so hard it looked like fog. By this time, we had the car filled with gas, and bought two extra cans and had them filled, and that took about the last cent we had. The man charged us ten cents a gallon for the gas, and just the day before it was nine cents; but we had to have that gas, for we knew if the snow kept coming, it would soon start to drift.

We finally got started for home. We got along pretty good for about fifteen miles, to the little town of Granada, about five hundred people. We drove up to a filling station and stopped. A man came out and asked where we were headed. When we told him, he said, all excited, “They are having a man-killing blizzard where you are going. You better put some real heavy chains on that car or you are not going to get very far.” How right he was.

By that time, it looked pretty bad and the snow had started to drift, so we put on truck-type chains. Now this was about 4:00 P.M. We filled up with gas once again and started on our way. We had about five miles to go to get out of the lowland and start up on the plateau country, while the storm was raging at 30 below zero and the wind had reached about seventy-five miles per hour, which made a chill factor of about 101 below.

As we got higher, the snow and drifting got worse. We had about eight miles to go from Granada to the small town of Hartman. We finally reached Hartman, about two-thirds of the way up to plateau country, which is miles and miles of flatland, no trees or rocks, no hills; only every four or five miles there would be a prairie dog town. We made our way east of Hartman about two miles. By this time it was 7:00 or 8:00 P.M., with snow drifts four feet high and still coming.

It looked like hell on Earth, and we kept thinking about what might be happening to the folks at home. We would have to run into each snowdrift, back up, and hit it six or seven times to get through, and just as we would get through one, here would be another. By this time we both were about exhausted.

We just sat in the car and talked it over, motor running all the time, knowing if the motor died, we would also freeze to death, and all of a sudden I saw a faint light up ahead and to our right. I said to Dad, “Look, do you see that light?” By that time it had gone out, and a second later it appeared again. We thought it must be a farmhouse.

We knew by now there was no way we could go much farther, so we inched ahead about a hundred feet, and there we were—right in front of a house! We left the engine running and locked arms with one another so as not to get lost if the light went out again.

The light would go off and on every second or two, because the storm was so intense; the snow was like talcum powder, driving right up our nostrils. We could hardly breathe. We had rags the size of big bandannas around our faces, pulled up close to our eyes, trying to keep our faces from freezing and at the same time trying to keep that awful fine snow from freezing our lungs. Walking in the wind was almost impossible.

It seemed like we would never reach that light, when all at once we stumbled and fell onto the porch of a house. We knocked on the door, and a man came and opened it. The first thing he said to us was, “Get yourselves in this house before you freeze to death!” We told him who we were and where we were trying to get to. “Well, you can’t go nowhere in this,” he said, and told his wife to get us some dry clothes and supper. So there we were for the night of March 28.

In the meantime, before we undressed, he put his fur coat and sheepskin mitts on and we all three went out and got our car off the road. As we stepped back on his porch, he looked at his thermometer, and it read 31 degrees below zero.

We stayed all night at this man’s house. Happened to be a dairy. Next morning, we got up about 4:30 on the 29th to help the good man feed and milk his cows, about thirty head. After breakfast, at 6:00 A.M., we looked out and no car could be seen. A drift had completely covered it up.

The dairyman said, “Let me harness my team of big horses and pull the car out of that drift and get it started.”

The car was completely full of snow inside and under the hood. The snow was packed so full the fan could not turn. We dug out the snow with our sheep-skin mitts and shovel until we got the engine clean. The man put his big horses to the car with a chain, and we finally got it started, after pulling it about two hundred feet through snow twelve inches deep.

By this time, it was about eight o’clock. We tried to pay this man, but even to mention pay was almost an insult to him, for he said we might have grave things ahead. So we thanked him, and off we went.

The storm at this time seemed to be letting up a bit. We still had about thirty miles to go, and getting started about eight, we had in mind getting home by twelve o’clock, which would give us about four hours to make thirty miles. But no such luck. As we started out, you could hardly see ten feet at a time. We figured taking the back road, where there was no fence, would help us, because the snow had blown off in places. We were making about five or six miles an hour to start, hitting snowdrifts four or five feet high, plowing right through them. Sometimes it would take three or four tries to get going again. All this time we were going east, which made the drifts cross our path. We fought them for four hours and got only about fifteen miles.

When we were climbing to higher country, our road turned north, so now we were facing into the storm. Visibility got worse by the minute. Under the car, around the wheels and all, snow had driven in so hard that we had to get out, take tire tools, and dig out so the wheels could turn.

Visibility was almost zero. We had trouble at times seeing the hood ornament. The car was a 1928 Chrysler Imperial four-door sedan, and it sure must have been a good one, for the punishment it took, words could never tell. As we inched along in low gear, my dad would say, “Go right,” or, “Go left,” as he noticed a fence post now and then. We were at nerve’s edge, trying to stay between two lines of fence posts. You could clear your throat and spit out, and the spit would freeze before it hit the ground.

We had kerosene in our car for anti-freeze, and by this time the stench of the motor was about to get to us, for if anyone ever abused a car, we did. It had quit snowing by now, but the wind was blowing so bad you would never know. It was whipping that snow like a sandstorm, blowing it right into our clothes. Our car by now was almost full of snow, for Dad would roll the window down, trying to see a post or something to guide us by.

As we inched north, he remarked, “Now, if we can get across the ravine”—a dry creek called Horse Creek, about a mile ahead—“we could make it home by dark.” About one o’clock we finally reached the creek, which was a deep ditch across the road. We could not see at all but could feel the car going downhill, so we stopped, left the car running, got out, locked our arms together so as not to get lost from each other, and tried to see what was ahead before we got stuck for good. We had left the lights on, but they were not visible over thirty or forty feet.

We could see a drift about sixteen feet high, almost like a knife blade, across the road. No way could we get on top or walk around it, for that would have been suicide, we knew. Only one chance left: Drive through it, punch a hole in it. This drift was about sixteen or eighteen feet through. We knew this was life or death, for if we stopped in that drift, we would soon suffocate.

So, we drove up to the drift, about five or six miles an hour, and punched a good hole. We backed up and hit it again, and again. We were doing the impossible, but this was the last barrier, we thought, for this was flat country, and this creek was the only one in thirty miles. We figured the drift could not be over twenty-five feet thick at the most, so after punching a hole about ten feet, we backed up on dry road, about a hundred feet, where snow had blown off, and hit that hole wide open. Very foolish, but in desperation we tried it. It worked. The snow had blown clean on the north side of the big drift, giving us footing to keep going.

Tears almost came to our eyes, knowing we were headed home. So here we go. Dad would say, “Right.” I would go right, and then he would say, “Go left,” and I would go left. And then he’d say, “Go right,” and I would go right. So the next three miles we would go like this. As we went north, we came to a turn or correction line in the road, which was a long curve. The road was built up at this point, and we made it okay by feeling our way around the curve by the rise in the road. The wheel would get close to the edge; I would pull back. If you’re not able to see where you are going, it’s not easy. We got around that curve and headed north again.

Going got a little worse, more snow, larger drifts, and by this time we were a lot more tired. Here it was 3:30 P.M., the same day we left the dairy, and we had ten miles yet to go. Because I was getting awful tired and nervous, the right and left driving got to me. Dad said, “Go left,” I went right, and off in the ditch we went, in snow four or five feet deep. In no time the car was covered over with snow. Here we sat, like in a dungeon, being buried deeper by the minute.

By this time, it was about four o’clock, and all hopes of getting home were lost. So there we sat in the car, not knowing exactly where we were, the engine dead, and knowing that staying there meant freezing to death. So my dad, being an old-timer and raised in the north country, said, “Brother, did you see the big corner post back there, a quarter of a mile, on the right side of the road?” I told Dad I believed I had. That corner post was the end of a fence for us to follow, and facing a blinding storm made us wonder just where we were and just how far we had gone for sure since we sighted the corner post; but we knew the country and almost every post in the country, and a big one was a landmark. There was no timber in this country, nothing but bald flatland stretching for miles and miles, only the stars at night and wind by day to guide you. Now, as we both knew, the wind never changes directions once a man-killing storm strikes. The wind that had caused us so much hell for almost two days all at once became our guiding light, for now that fierce wind might help us to find our way. If only we could muster enough strength to endure the cold.

The big corner post made all the decisions for us. We walked for about fifteen minutes arm in arm, for unless we had our arms linked together, we could not see each other most of the time. We knew getting separated meant only one thing, lost and dead, and when one of us fell down, we would stop right there and get our bearings again before going on. We could not see much over two to four feet. We knew we had to get somewhere pretty soon.

Now, we were pretty sure that corner post was a northwest corner of Andy Reinert’s ranch and that his small frame house was about a half mile east of it. We talked about how to stay alive by breathing in through our nose and out the mouth, so as not to freeze our lungs. We also talked about keeping our blood stirred up by swinging our arms and bending over and back again, so as not to let our blood start freezing in our veins. By now the snow had driven into our clothes, making exercise a strenuous task. Our masks were frozen stiff, for our breath would freeze and make solid ice over most of our face. We would walk east or sideways to the wind for about a hundred yards, then stop, stand still, unlock arms, and swing our arms so as to get our blood going again.

Then we’d turn south with the wind to our back. That way we would be going straight south again, and by doing that, we would not miss the fence that went east from that corner post. As planned, we ran right into it. Russian thistles, or tumbleweed, some as large as a washing machine, grow in the summer, and when frost comes they break loose from the ground and the wind starts them to rolling across the prairie. If a fence happens to be in their path, it stops them, making high piles, so when snow comes blowing, they fill with snow, and you have a very high drift. So, here we were behind a big pile that had built up on the fence, and snow had drifted about six feet high, so the fence was hard to follow. Thank God most of the drifts were on the south side of the fence and we were trying to go east on the north side!

But there was one catch to it. How were we going to know when we got to Andy’s ranch? We kept tapping the fence every five or six feet or so. We knew he had a gate in that fence that led to his house, but if for some reason the gate was closed, we could walk right by and not know it, so we had to keep watch and keep tapping the fence to make sure this did not happen. It was still twenty-five to thirty degrees below zero, and the wind had not let up yet, about seventy to seventy-five miles per hour. Icicles four to six inches long hung down from our mouths.

As we continued east, tapping the fence, Dad jerked my arm and stopped. He leaned over and shouted, “No fence!” So we figured we had reached the barbed-wire gate that was open and that led to Andy’s shack, but leaving that fence meant losing our security and giving us a feeling of being lost if luck did not come our way. We knew if we missed that shack by 20 feet, we could go on and on.

So, what next? We knew that Andy’s shack was about a hundred yards or so south of that gate, so we locked arms again and went south. I could not see my dad most of the time. We walked south and felt ourselves climbing up a steep grade. We knew the ground was level, so we kept on climbing higher and higher, and all at once we both fell, about 12 feet. The snow had drifted around the shack and left about three feet all around the house, and that is where we found ourselves.

We picked ourselves up and felt around the house to the east side, knowing the door was on the east. I knocked on the old wooden handmade door, and Andy opened it. The first thing he said was, “Don’t knock on the door, get the hell in here, and how in the hell could you live out in that storm?”

We told him our story, and his wife got us something to eat and a shot of good whiskey. Then, Andy asked if we would help kill his cattle, which were freezing to death or suffocating, for snow turns to powder and gets in the lungs. So we grabbed ball-peen hammers and put over a hundred out of their misery. We would knock them in the head, and they never fell. They just froze to death standing up. He wanted to kill those cattle at a time when they could not feel anything, for if any had lived, they would never be able to walk again. As we went through the hundred head, some had their tongues hanging out; that meant the powdery snow had already closed their nostrils and they had tried to breathe through their mouths. We never stopped to hit them; they were already dead. I saw two or three big bulls in that bunch, but their fighting days were over.

And then, as we were finishing killing cattle, a rancher rode up and said, “Come quick! I found the lost school bus, with the kids all dead!” He was in his wagon with a big team of horses. He was shouting with all the power he possessed, but at first we didn’t understand what he said. He bellowed out again, “Come quick!” We all ran to him, thinking he might be crazed by the cold. When he came closer, we could see who it was. He was covered with ice, and the neck of a bottle was sticking out of his fur coat. The poor man had his eyes almost froze shut. It didn’t take long to realize something very bad had happened. We wondered if he could take us back to the bus, as he was crying, “My kids are in there!” At this point no one knew there was a bus lost, for Andy did not have any kids in school. This was now about 5:00 P.M. on the 29th. It was getting dark, getting colder, not snowing so much, but still blowing. The man in the wagon was almost frozen, and his speech was blurred from exhaustion, for he had been lost himself, hunting for those children all night and all that day and stumbling on to them by chance.

We ran in the shack, picked up some corn-shuck mattresses, and beat those horses over the back to get to that bus as quick as possible. It was a little over half a mile. We drove the wagon up to the north side of the bus, for the snow had drifted high on the south side. The door of the bus was also on the south, making it almost impossible to get to. We noticed a broken window as we drove up. We got to the door, finally, by frantically digging it out with our hands and feet but noticed it was not latched. There was a cold silence; only the howling wind could we hear. As we opened the door, there was a boy slumped over the steering wheel, no coat, and just able to moan. We found out later he had given his clothing to the younger ones. We grabbed him and slid him out the door. The rest were huddled together with arms and legs frozen stiff. We frantically took them to the door. As I looked back to the corner, I almost fainted, for inside that bus I found my girl friend, delirious and almost frozen to death. The message I was receiving back at the store the day before really meant something, but I did not know it then. Her legs and arms were froze, her face a pale blue. She could barely roll her eyes and could speak no more. She was almost at life’s end. I grabbed her gently but as fast as I could and pulled her to the door, for snow had packed in over three feet deep in the bus. I knew she went to that school, but she normally rode a horse to and from school. The look on her face and the rest of the children, no man can explain, for the snow had blown in and packed so hard you could barely move them. It was a horrible sight and feeling, and why did this have to happen? Three of the kids were dead, and the rest were delirious and frozen near death.

Four of us grabbed kids like they were bales of hay. It took about two minutes to load a wagonload of 17 frozen kids. There was not a word spoken, for we all knew what was ahead and what had to be done. We covered them up and climbed in the wagon. Then we headed back to Andy’s shack, which was a little over half a mile away. The horses were big and strong, so the rancher never spared the whip.

Back at the little ranch house were Andy’s wife, who was expecting their second child, and their two-year-old son. Andy said, “I’ve got to get my wife and kid out of here quick,” for on that bus were a sister and a brother of his wife, and we were bringing them to the house not knowing if we could save them or not. So about that time a neighbor showed up, and he bundled up Andy’s wife and son and took them about four miles east of Andy’s house. That left the empty house with four men and seventeen frozen children. As we were carrying the children into the house, two more died in our arms. We took them to the back room and laid them on a pile of snow, for snow had blown in and had covered the floor.

It looked like a hopeless case. All men, no medicine, no phone, no way to get help, and not much experience with freezing and dying children. The house had six inches to a foot of snow on the board floor. Snow had blown in through the cracks. By this time three or four fathers and ranchers, who had been hunting all night and all day for the kids, had come. One of the fathers found his only child, a boy, dead. He also had been hunting all night and day for the bus, only to find his son at Andy’s house in the back room. But what a hero he was! This man worked all night along with all the rest and up to about noon the next day, when everyone started the search for the bus driver. Finally, he collapsed in the snow and was taken to a hospital with pneumonia and did not get to go to the funeral of his only child.

In desperation we started rubbing the kids down with snow. We cut the top of a fifty-five-gallon barrel out and filled it with distillate—what’s now called diesel fuel. We stripped the kids, one by one, and put them in the barrel of distillate, trying to draw the frost out and get circulation going again, and keeping the temperature as high as possible in that shack, which was about forty to fifty degrees, using cow chips as fuel.

Some of the kids started to come to and began to ask where the driver was. We fed them warm water and potato soup. We had kids laying on horsehides, saddle blankets; anything that was loose on both ends, we used it. Kids would scream with pain as the frost started to come out. We would grab snow off the floor and rub their arms and legs. We knew this had worked in times past, for every man there, including myself, had experienced frozen feet or hands before.

We had to get a doctor and news to the outside world fast! Everyone was frantic, so here is what we did. This was now about six or seven o’clock at night on the second day. Some of the men raced by horseback and got three or four old cars at a large ranch nearby that belonged to ranch hands that worked there, and chained them bumper to bumper. They started out for a phone and help at Holly, Colorado, thirteen miles away. They had to go back the same road Dad and I had come up that same day. They had to go with the wind, or south. They also had to go through the same high drift that took Dad and me so long getting through, and the deep dip in the road. By using that many cars, it worked like a bulldozer, and the back cars pushed the front car right through all the drifts. In about an hour they reached a phone.

In the meantime, while they were gone, Andy and I went back with a team of horses to the bus for the dead we had left. It was dark, and the moon started to show through the clouds, and as we drove along, still about twenty below zero, the wagon wheels would sing that crunching noise made by running over the frozen snow. It was not a very pleasant mission, but it had to be done. When we arrived back at the bus, we backed the wagon up to the open bus door. Andy looked in and turned his head and said, “Elbern, can you go in and get those kids?” What Andy saw inside that bus was a little boy with blood frozen on him from his head to his waist. As we found later, the children had slapped each other in desperate attempts to keep everyone awake. I told him to hold the reins of the team and I would go. Inside, the bus was half-full of snow and the children frozen together. One was a girl of fifteen, who died on her birthday; one girl, seven, turned out to be the driver’s daughter; there was a boy about eight years old. I pulled them apart, put them in my arms, and carried them out and laid each down in the wagon, which had bundles of feed at the bottom. Then we both got in the wagon and drove slowly back. The fathers were still all there, taking care of the children, working feverishly to save each one, but the families at home did not know what was going on. Someone had to go and notify mothers and families.

So, me being the youngest in the bunch and raised to be a good horse-rider, they picked me for the ride at about 10:00 P.M. that night, to spread the word to the mothers at home. Andy said, “Go out and saddle up that brown cutting horse and ride the route and tell the wives and families what has happened and who is dead and who is alive.”

I didn’t relish the idea, but be strong I must. The storm had slowed down, still drifting and twenty to 25 below zero. My first thought was I never saw this horse before. So four or five men jumped up and said, “Let’s help that poor boy get started on his way.” We grabbed our coats, our masks over our faces, and headed for the barn.

Getting to the barn was not easy, but when we got the door open, the snow had packed so tight in the barn and so high the horses were above the door, and no way could we get in the barn or get the horses out. Several horses were kept in the barn at all times day and night so as to have transportation if needed, for the horse was the trusted way to travel. About once a week they would go out on the range and drive in several more and exchange. That way they had fresh horses and also allowed the others the exercise of the range. Because horses like to fight, they were always kept in stalls or separated from each other. Inside the barn they were standing on that packed snow, six feet deep. They were hanging themselves on their halter ropes, and no way could we get them out the door. So there was only one thing to do.

We ran back to the house, got crow-bars, and took enough roof off the barn so we could get the horses out through the roof. I found the horse I thought Andy was talking about. The saddle covered with snow was hanging on a peg up close to the roof. I took it down, but it was frozen stiff. I thought to myself, Maybe I better go bareback and leave the saddle at home, but, thinking again, With my clothes frozen stiff, how would I get on that horse without a saddle? I cleaned most of the snow off and put it on his back, noticing he had powerful front shoulders and legs from being used as a roping horse. He sure was the animal I needed and I said to myself, You don’t know what is ahead of you.

It took about five minutes of blowing my breath on the bit before I could put it in his mouth, for if it’s not warmed up, it would stick to his tongue. I then led him out and started to get on, but no way. The saddle was frozen, and he was in no mood to be ridden. So I led him about a quarter of a mile and at the same time got my own blood going again. I thought, Now is the time to pile on, for I had about fifteen miles to go and time was running out.

I turned him around and around, and about the third time around, on top I went, and away we went! Now thinking, What am I going to say, and how am I going to say it? But as I drew closer to my first stop, I said, Be strong and get going, five more stops till morning. I told my story as brief and fast as possible, and they wanted to go right then, but I told them everything was being done possible, and a house twenty-five feet by 25 feet barely holds seventeen children lying on a snow-covered floor and at that time about ten men. There was room for no more.

The horse proved to be an animal of strength, plowing through snowdrifts so deep he could not stand at times and fell to his knees. Despite the twenty-degree-below temperature, he began to sweat, and the sweat made long icicles, which made him look like a snowman with ice crystals hanging under his belly, adding extra weight he did not need.

I was pushing him to the limit. The storm was blowing over now, but the wind was fierce. Now I had one more stop to make, but it was going to be the hardest of them all, for it was about four miles from the last stop I had made and was a house built underground. I could easily miss it, for snow probably had covered it up. I took my bearings with the North Star and kept the wind to the side of my face, for this was close to midnight and no fence to follow. I looked to the sky, and there was a big star shining right in the direction I wanted to go. My horse by now was getting awful tired, so I got off and walked. While I walked, there were a lot of memories crossing my mind, for this was the house of the bus driver I was headed for. The driver and his wife liked to dance, so every two or three weeks the whole country would gather at this place to square dance.

There wasn’t much entertainment going on out on these bald flats, so the dance was a big hit. My dad, sister, and myself played harps for several years at most dances in the country. We got to know these people real well, and this was going to make my job even harder. These people were from the South and had never seen a storm like this before. I also knew this woman was softhearted and a hard worker. They had moved here a couple of years before and bought their 160 acres of land for twenty cents an acre, which was the going price at that time. They dug their house underground, for lumber was scarce and hard to get. This lady worked alongside her husband with pick and shovel, making the house, thinking, Now we have a house of our own, and now here I come riding up in the middle of the night with news that it’s all over.

I had to get back on my horse, for I was not making very good time walking. I almost rode past but noticed something sticking out of the snow, and sure enough I had hit it on the nail. I got off my horse, tied him to a post, and stumbled two or three times around the house, trying to find a way to get in, for snow had all but covered it. Finally, I saw a little upright building that looked like an outside toilet. I dug the snow from around the door. It was dark, snow was blowing, and it was about twenty below zero. I was about frozen myself, for icicles were hanging down and around my mouth. It was labor just to talk. I thought, My God, maybe they, too, are frozen.

I kicked the door hard several times, and at the same time this poor woman was trying to get the door open from the inside. She had stuffed the cracks with rags to help keep the cold out. Between her and me we finally got the door open. She asked me in. She did not know what had happened. She was calm, but cold and hungry, and was cradling her baby in her arms.

It was awful hard to tell her what was going on, keeping in mind she was all alone in this world. Her husband and daughter had already frozen to death, but she did not know. That was what I was there for. How do you tell her? I thought. We talked a few minutes. She sat down by a cold stove and said to me, “Where is my husband and daughter?” I began choking back tears. I told her what happened. You can imagine what was going through her mind. She paused a minute, looking to the floor, and then said, “Elbern, I don’t have hardly any food and nothing to burn in that stove, so I better go with you.” And when it began to sink in what I had said, she broke down and cried. I tried to console her the best I could. Finally I told her if she could hold out till morning, someone would come after her.

Then I headed back to the ranch where the children were. It was then after midnight. I saw my horse was getting awful tired. His shoulders began to tremble, so I got off and walked. I could walk on top of the snowdrifts, but he would break through. In places he would go belly deep and I would be standing on top. All the time I kept wondering what was going on at home, but I thought, Look what those poor kids and parents are going through at this point!

I got back to the ranch about 1:00 A.M., unsaddled my horse, and turned him loose among the hundred head of dead cattle, all standing up. Those cows, calves, and bulls looked like ghosts in the night. Well, I asked myself, is there anything more can happen? And there was.

You can imagine what it looked like inside the house. There was water, mud, and slush all over the floor, snow still three feet deep in the corners, and that many people in there made a foul air. Tin plates and forks and spoons on the floor in the muck. Some tried to feed themselves, but their frozen arms would not work and could not hang on to anything.

Now my job was to carry cow chips to the potbellied stove until morning. About 2:00 A.M., an hour after I got back to the ranch, the first doctor arrived with a caravan of six or seven cars, from Tribune, Kansas, twenty-one miles away. It took about five hours for that caravan to reach the little ranch house. On arriving about 2:00 A.M., the drivers found no shelter, for the little ranch house would hold no more. But they thought of that before leaving home, and they brought with them loads of quilts and blankets, expecting the old cars and the sky above to be their hotel rooms. A doctor from Holly came, bringing medicine and another nurse, making the shack more crowded than ever. By this time the children were all coming to, crying, screaming, needing to go to the bathroom, which was buried in snow out in the yard. The children still could not walk, so we had to carry them.

As soon as the doctors were there, they went right to work. They said, “Let’s get these kids to a hospital quick!” But “How?” was the question. When morning came, help started to pour in from everywhere.

A big cabin plane came roaring in from the west. I never saw such excitement. It circled a time or two, and we rushed out to signal where it could land. It was from Denver, and then a smaller plane came in from Lamar, sixty miles away. Just north of the ranch lay 160 flat acres, so both planes landed, bringing doctors and nurses. When the planes arrived, the doctors and parents were already preparing the children for the trip to the hospital. The children had to be carried about a quarter-mile through knee-deep snow, but there was lots of help. Two people would lock hands together, and two more would place a child in their arms, and so it went. They all got to the planes about the same time.

We loaded all the children on both planes, wrapping them in quilts, blankets, and heavy coats, for the smaller plane had an open cockpit. We bid them good-bye. The pilots had been keeping the engines warmed up all this time, for it was still fifteen below zero. Then one of the pilots warned everyone to get out of the way, for he was in a hurry to get moving. He wound the motor and headed into the wind, spraying snow like a storm, and the other followed, and in 45 minutes they were at the hospital.

Now, we still had to find the bus driver. By this time there were 150 people from everywhere, so they decided to walk about a hundred feet apart and cover the ground they thought he might have walked. So, after the children were off and gone, we all lined up and took a one-half-mile-wide path, going all directions from the bus.

As we walked, I noticed a man on a horse coming in the distance. He seemed to be in an awful hurry. He rode up to me and said, “I hate to tell you this. Your sister also perished at her schoolhouse, back home.” My dad was about fifty feet from me, so I called him over and told him the news I had just heard. I looked at my dad and he looked at me. We both said, How could this be? For she had been taught from the time she was a little girl not to trust those awful storms. Dad always said, “Kids, I have seen people freeze to death before,” and he cautioned never get out where you can’t get back. It was almost more than we could take.

We dropped out of the manhunt and went back to the ranch. There were a lot of people milling around the yard. We told them what we had heard, and everyone was eager to help. By this time they had let the horses loose in the corral, so we rounded up four big work-horses, dug the harness out of the snow, put the one team to a wagon, and trailed the other two. We took a big rope along to pull the car out.

It was completely covered with snow. We dug down, and it took all four horses to pull it out. The car was packed so full of snow inside and under the hood that it took an hour to dig out around the engine. We pulled the car back to the ranch house where all the children had been and set a fire under the engine to thaw the ice and snow. Finally, we got it going. Dad and I then got in and started for home. By this time there were tracks everywhere, so traveling was much easier, but in some places the wind had drifted the tracks shut, making our progress very slow and hazardous.

There were no graded roads in that area. The only roads were ruts, the result of wagons and old cars traveling in the same tracks for years. They would grind into the earth, and the wind would blow away the dirt, making a deep rut, and that is what we had to avoid if we expected to reach home.

So, we thought if we went east and took the prairie where the snow was not very deep, we could finally make it. But, between where we were and home, about ten miles, there were three or four drift fences, erected for the purpose of keeping cattle on the range from straying. The gates in them were where the ruts were, so in order to keep going, we had to get up speed enough to drive right through those drift fences.

We were in a state of shock. Nothing seemed too big for us to handle; we had only one thing in mind: Get home and fast! The posts were about 16 feet apart, so the first fence we came to, Dad said, “Give it hell,” and right through the fence we went. At one point, one of the barbed wires came across the head-lights, one across the radiator, and the third right across the windshield. We hit that fence full speed ahead at about twenty-five miles per hour. We had the car in low gear for the power that we had to have to snap all three wires at the same time and not stall. There still were three more to drive through. As we came to each fence, we drove right through. The last mile was good going. It was awful cold, but the snow had stopped. We could see the house by now and braced ourselves for the worst.

As we pulled up to the house, the door opened and Edna came out to find out where we had been. Dad and I both started to cry, and my sister said, “What is the matter?” And after gaining composure, I said to her, “You are supposed to be dead!” We were so overjoyed we could hardly talk. We’d had no sleep or rest for two days and one night. How the rumor got to the man on the horse no one will ever know. What did happen was that the man who was so concerned about my sister turned out to be my brother-in-law six months later. After the driver of the school bus was found, this young man showed up at our house on the same horse in the middle of the night, to find his bride-to-be living and well.

My sister, as it turned out, had kept her children in her schoolhouse about thirty hours, until the storm was over, and saved all, and that is why she was home to greet us when we returned from our ordeal.

After we pulled ourselves together—we were still in shock, I suppose—we drove back that same afternoon to the bus, just to take a second look and take some pictures. We heard growling. Inside the side door was a mongrel dog, a small one, and it turned out to be the pet of the little girl who had been the first one to die.

The dog had come some six miles to that bus, and he was guarding a beret he had found that belonged to his little mistress. He guarded it until he himself froze to death. How the dog found the bus, only God will know!

Later we found out everything that had gone on in the bus. Many kids came to their schools on horseback or in buggies, but this particular school had a 1929 Chevrolet six-cylinder bus. When the storm began, the teacher and the bus driver decided home was the best place for the children, but the driver didn’t much want to start, thinking maybe it might get worse before he could make his rounds. But against his better judgment they loaded the kids, twenty in all, and started to take them home. The kids rejoiced, thinking, No school, we are going to have a vacation for a few days! and all climbed in the bus, singing and happy as larks. Some started to eat their lunches, for they had a long ride home.

It then was about nine o’clock the first day. As he left the school, the driver soon realized he could not see where he was going. He looked back, and the schoolhouse was out of sight. He knew a graded road running north and south was about a mile to the east, and he thought with luck he would hit that road and follow it. But instead, he went in circles, around and around in what is known as Dead Horse Lake. No water in it.

The storm by now was at full speed, visibility was zero, and snow was beginning to turn to powder. The temperature had dropped from sixty above to close to zero. The driver could not see a thing, all landmarks went out of sight, and he asked the kids to look for something they might recognize. The driver decided he would try and get back to the schoolhouse, for he knew he had not gone very far.

He started up again, and as he circled the lake bed, his turns got bigger and bigger until he came to the outer edge, and in his last circle he went straight across the road he was searching for. The front wheels made the bar ditch, but the back ones did not. The engine was only running on three or four cylinders, and it died for good right there.

The kids started to clap their hands in joy and hollered, “We made it!” for they always crossed a ditch getting in and out of the schoolyard, and they thought they had got back where they started. But the driver knew better and told the kids, “No, we are somewhere else, and lost.” That scared the kids, and they started asking, “Now what are we going to do?” The driver told the kids, “I will dump the water out of this cream can”—a ten-gallon can they had hauled water to the school each day in—“and build a fire.” So he tore the seats out and got a fire going inside the bus. There they sat all day and temperatures dropped to thirty below zero, and it wasn’t long till the bus started to fill up with snow. Things started to look bad, and the driver told the kids, “Keep moving, or we all are going to freeze.” He told the kids stories and tried to keep them close to the fire. They burned up all the seats; then they burned their books.

Still no help. By this time, about nine hours had passed, the kids had already eaten most of their food but had no water, so they licked a little snow now and then to soothe their throats. For the past several hours, all whooped together in hopes someone might be passing by and hear them. They were freezing to death and knew it. Night was coming on, and the children began to get tired. The driver tried in desperation to keep the kids from going to sleep. He would watch every child; but his hands became so numb, and his mind became slower and slower. Knowing what was taking place, he asked some of the older children to rub each other’s faces and legs and arms. That seemed to be the only and last thing that could be done before death set in. He even coaxed them to fight, to get their blood stirred up.

One of the kids broke out a window on the north side, letting snow by the bucket fall in. The bus soon filled up. That made moving about worse by the minute. They had no light; they could not see one another, snow blowing in and kids tramping it down till it was about three feet deep in the bus. Keeping those kids on top and not trampling the small ones was almost impossible. This went on all night, and still help was not in sight. Some of the kids heroically gave their coats to others. They prayed to give them strength to hold out till morning. By morning, when it was just light enough to see, the driver tried to rally the children but noticed two would not move. They were already frozen stiff. One of them was the girl fifteen years old. She died holding her sister on her lap. The other was the boy about eight. The kids pulled them to the back of the bus and laid them on top of one another, facedown, for the oldest girl froze with her eyes open and the kids thought she was staring at them. That scared the rest, and panic set in.

Now day broke, and still no help. Snow had blown in so deep their heads were about to touch the roof. The driver said, “I’m going for help; pray for my return,” and reached down and kissed and hugged his daughter. The kids that were still able to speak begged the driver not to go, for two of the older children had just got back from crawling on their elbows and knees for about a hundred feet down the bar ditch and could hardly get back. But he knew staying there any longer would help none. He turned and almost fell out the door. He never saw them again. He was found the next day about two miles south of the bus in a wheat field, both hands cut to the bone by barbed wire, trying to follow the fence. This was a brave man.

After he left and before the kids became delirious, they looked out and saw our car and screamed, “Help has come!” But to the sorrow of all, we left the car, not knowing that we had come within two hundred feet of hitting the bus broadside.

I have often wondered why we could not have traveled that extra 200 feet. We might have been able to save two more children.

I attended the funeral of all six. They were buried in a row, as airplanes flew overhead and dropped petals of flowers, while the choir sang “From Every Stormy Wind That Blows.”

Just 200 feet north of where our car went in the ditch is a marble monument that marks the spot where these courageous children lost their lives.

I had to grow up real fast in that thirty-six hours of hell and can still see those frozen faces. The only nice thing I can say is, we lost almost everything we owned, but we all lived through it. We could start over.