Previously unknown, a map drawn by Lord Percy, the British commander at Lexington, sheds new light on the perilous retreat to Boston 250 years ago this month.

-

Spring 2025

Volume70Issue2

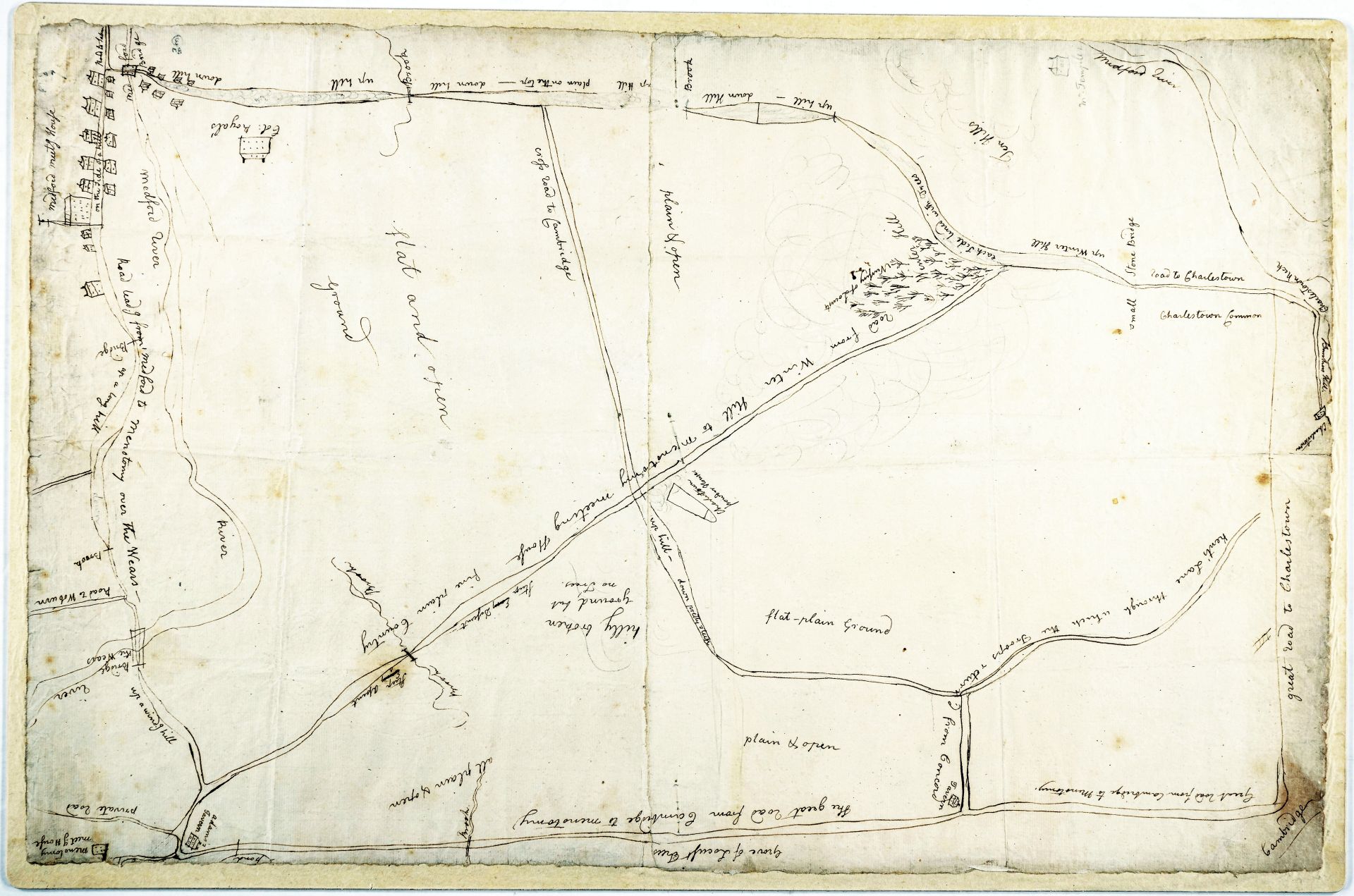

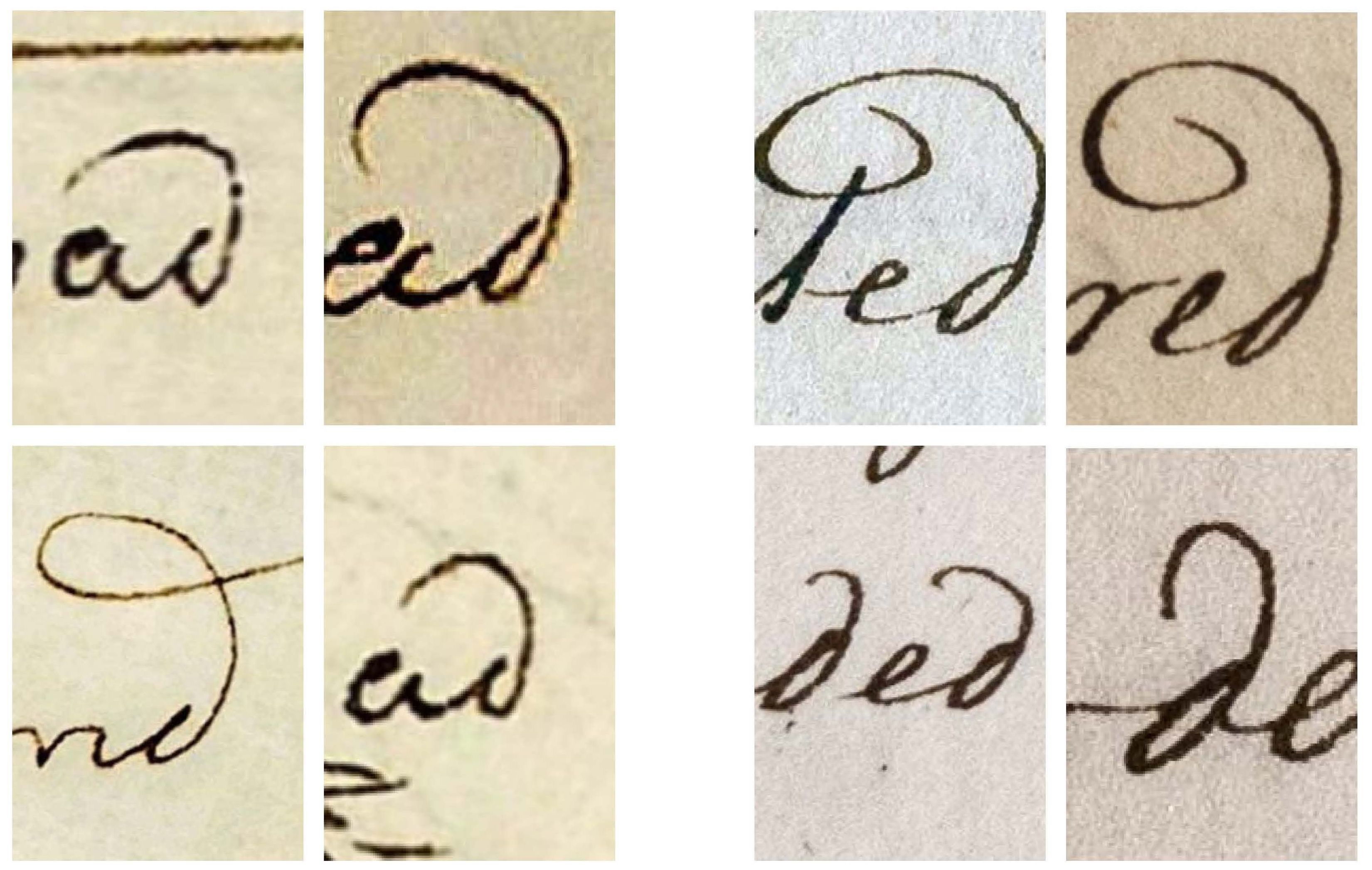

I could scarcely believe what I was seeing. Despite generations of research and hundreds of books on the American Revolution, here was a critically important, yet previously undocumented treasure—a detailed map of the retreat of British troops from Lexington drawn by Lord Hugh Percy himself, the general who commanded those regiments.

Sketched within hours of the first significant armed conflict between Britain and its upstart colonies 250 years ago this month, the faint but detailed drawing appears to be the first record of the first battle of the American Revolution.

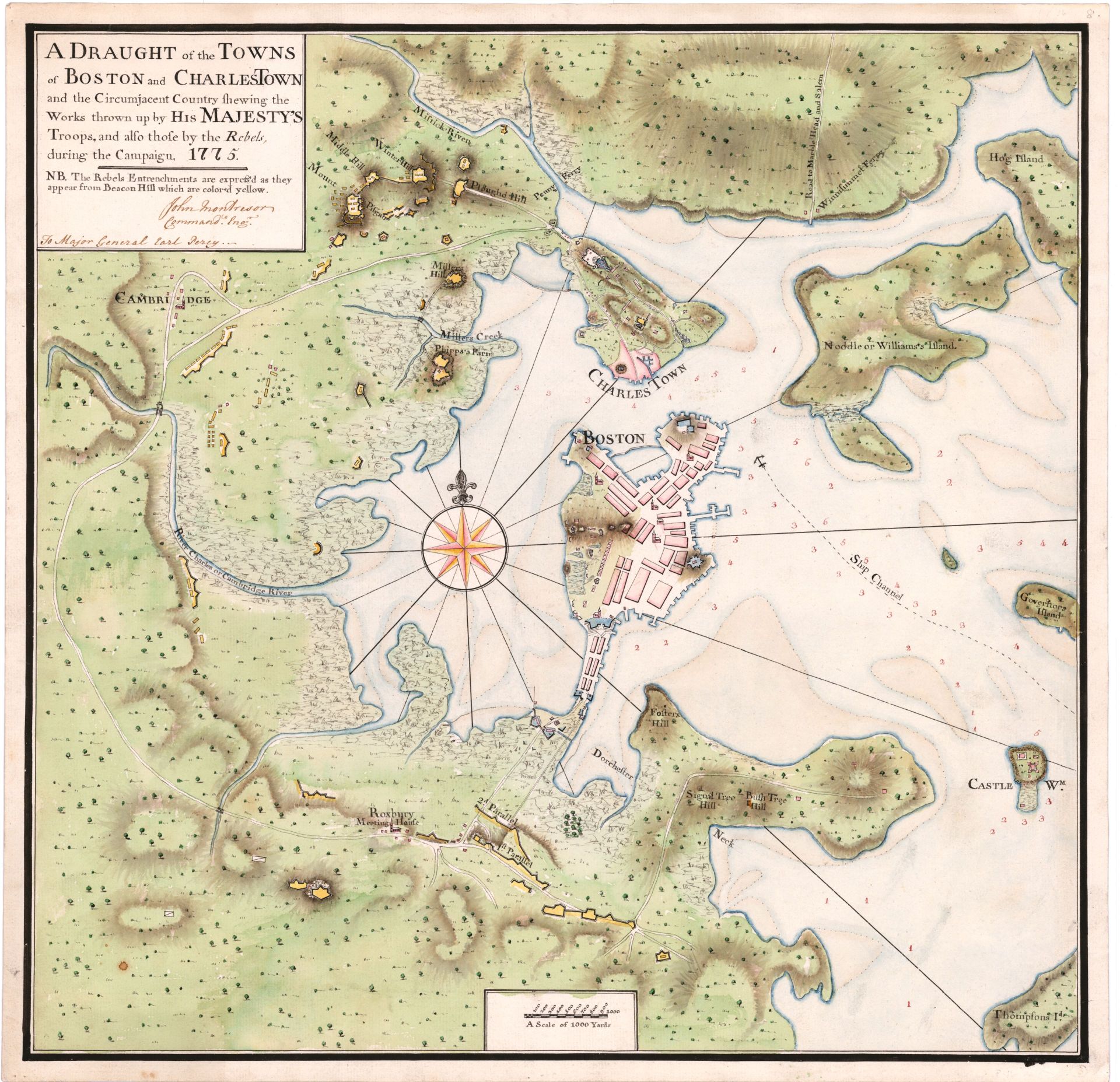

The map rested on a long table with an array of other extraordinary maps of the Revolution, many of them meticulously drawn and colored by hand. A team from American Heritage was deep in the interior of ancient Alnwick Castle near England’s Scottish border, talking with Ralph Percy, the 12th Duke of Northumberland and a direct descendant of General Lord Percy, about the dozens of maps his ancestor brought home from the American War of Independence. They had been stored for over two centuries in a wooden box, but the Duke's father had seen they were taken better care of. The wealth of hand-drawn maps would make any historian swoon.

“They are quite extraordinary,” the Duke said. “My father was very proud of them.”

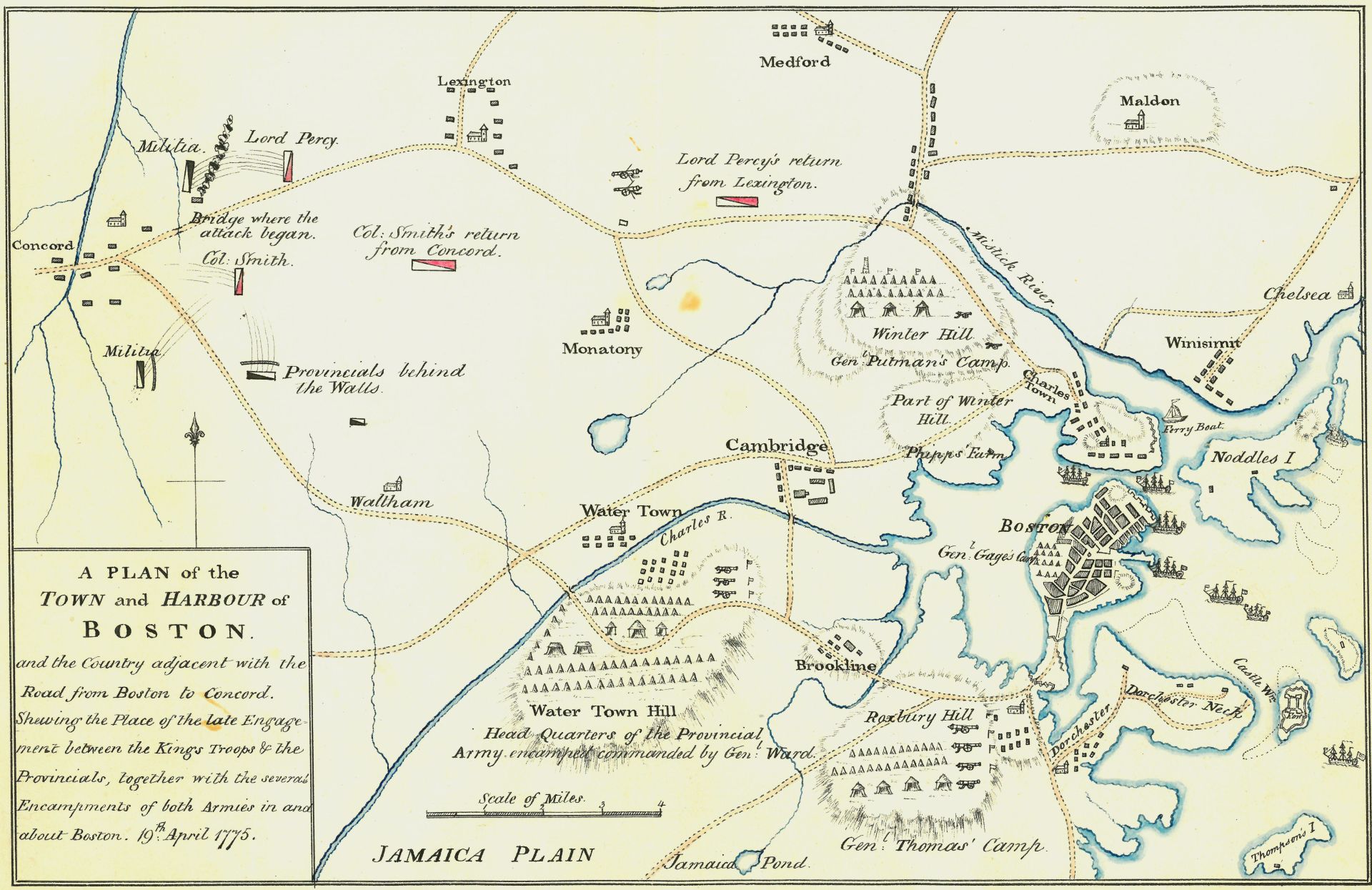

A second map, dated April 19th, 1775, and hand-drawn by one of Percy's engineers, showed "the Place of the late Engagement between the King's Troops & the Provincials." It has numerous symbols for military units with labels such as "Militia" and "Provincials behind the walls" with thin lines of musket fire pouring out at "Col. Smith" and "Lord Percy." As is often the case with records created just after engagements, it includes numerous small errors.

On that morning in 1775, General Percy rushed with his reinforcements from Boston to support the King’s beleaguered troops who had marched to Concord in the middle of the night to destroy Colonial military supplies and, if possible, capture Sam Adams and John Hancock. General Thomas Gage, Royal governor of Massachusetts and commander of British forces in the colonies, had issued his top secret orders after receiving instructions from the King and Prime Minister Lord North to be more firm with the colonials after the Boston Tea Party.

Gage had told almost no one about the Concord raid, not even Percy, his second-in-command, until hours before. Lord Percy decided to take a walk in civilian clothes on the streets of Boston and was surprised to discover that word had gotten out. Speaking with a group of local men gathered on a corner, he learned that they already knew about the supposedly secret mission.

Some historians suspect that Gen. Gage’s beautiful and charming wife, the American-born Margaret Kemble Gage, may have tipped off her friend Joseph Warren about the coming attack. Margaret was known to have sympathies with the colonial cause. (After the fight at Lexington, she was sent back to England, and by some reports, Margaret and her husband remained estranged, but no hard evidence supports the possible intrigue.)

Sensing trouble for the raid on Concord, Gen. Percy departed Boston around 9:00 on the morning of April 19 with four regiments under his command, including the King’s Own, the Royal Irish, the Royal Welch, and Percy’s Fifth Foot regiment. They marched quickly the fourteen miles to Lexington, and on arrival were shocked to meet with Col. Smith’s men returning from Concord with many casualties. Percy immediately set up a defensive line east and west of Munroe's Tavern, and his two cannons fired to hold off the rebels.

After regrouping and treating the wounded at Munroe Tavern, Percy led the combined force of about 1,700 British regulars on the long road to Boston. There was persistent harassment from the Americans, as thousands of militia swarmed toward the fighting from all directions. To deal with the militia shooting from behind rocks, trees, and houses, Percy assigned flankers to try to clear the areas around the main forces marching on the road.

The day after the conflict, Percy wrote his father that he marched out to a town in the country and met the returning troops, who had been “sharply attacked & surrounded by the Rebels, having fired away almost all their ammunition. I had the happiness, however, of saving them from inevitable destruction, & arrived with them at Chastown, opposite Boston, ab' 8 o'clk last night, not, however, without the loss of a great many, having been under an incessant fire for 15 m[ile]s.”

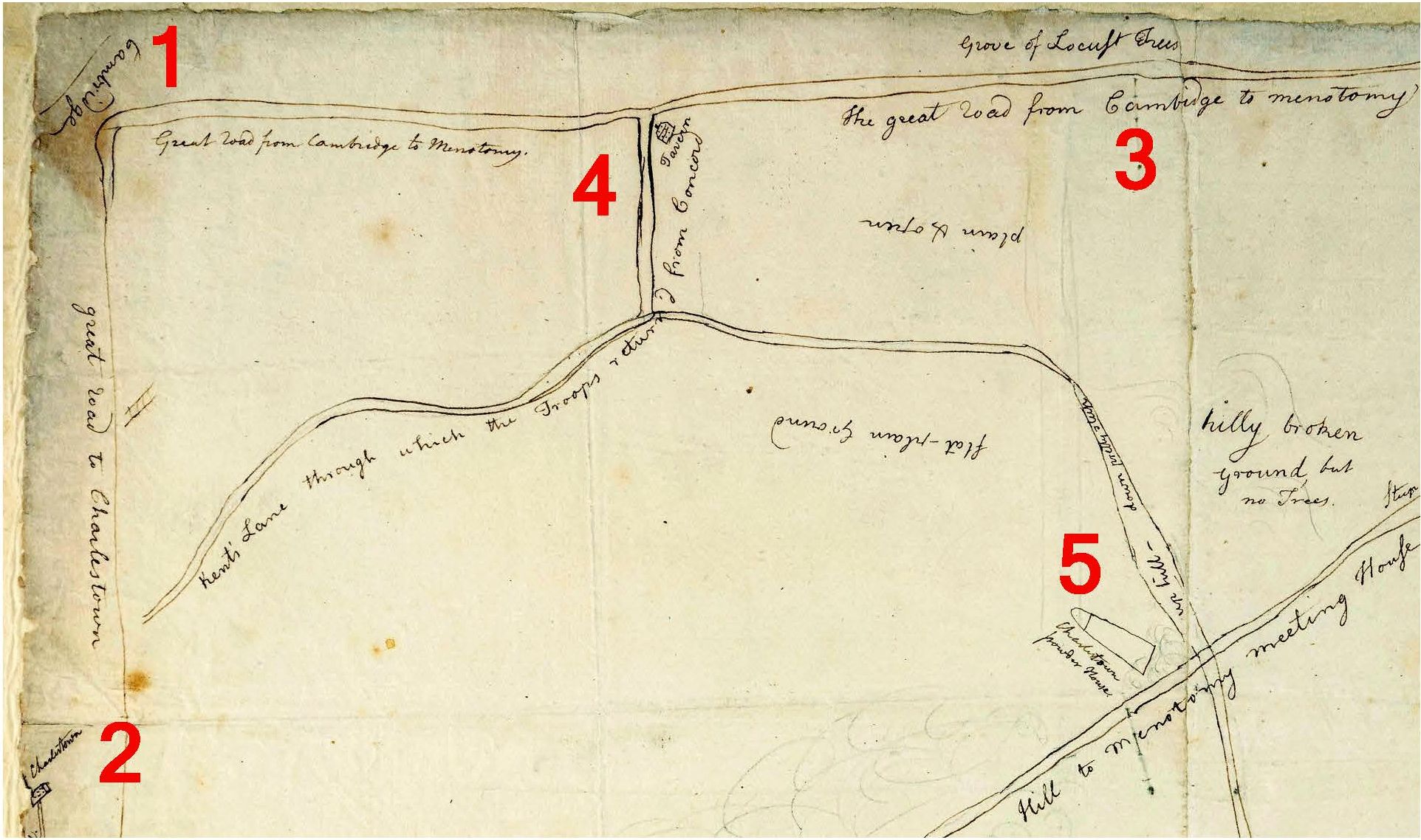

On the newly found map, Percy had drawn his route from Lexington to Menotomy and back to Boston. “He's sketching the line of march,” observed local historian Michael Ruderman, studying the new Percy map. “It's the theatre of battle, the hostile territory he had to travel during the afternoon. And he's sketching the landmarks that were significant to him like the Old Powder House tower that he passed on his left."

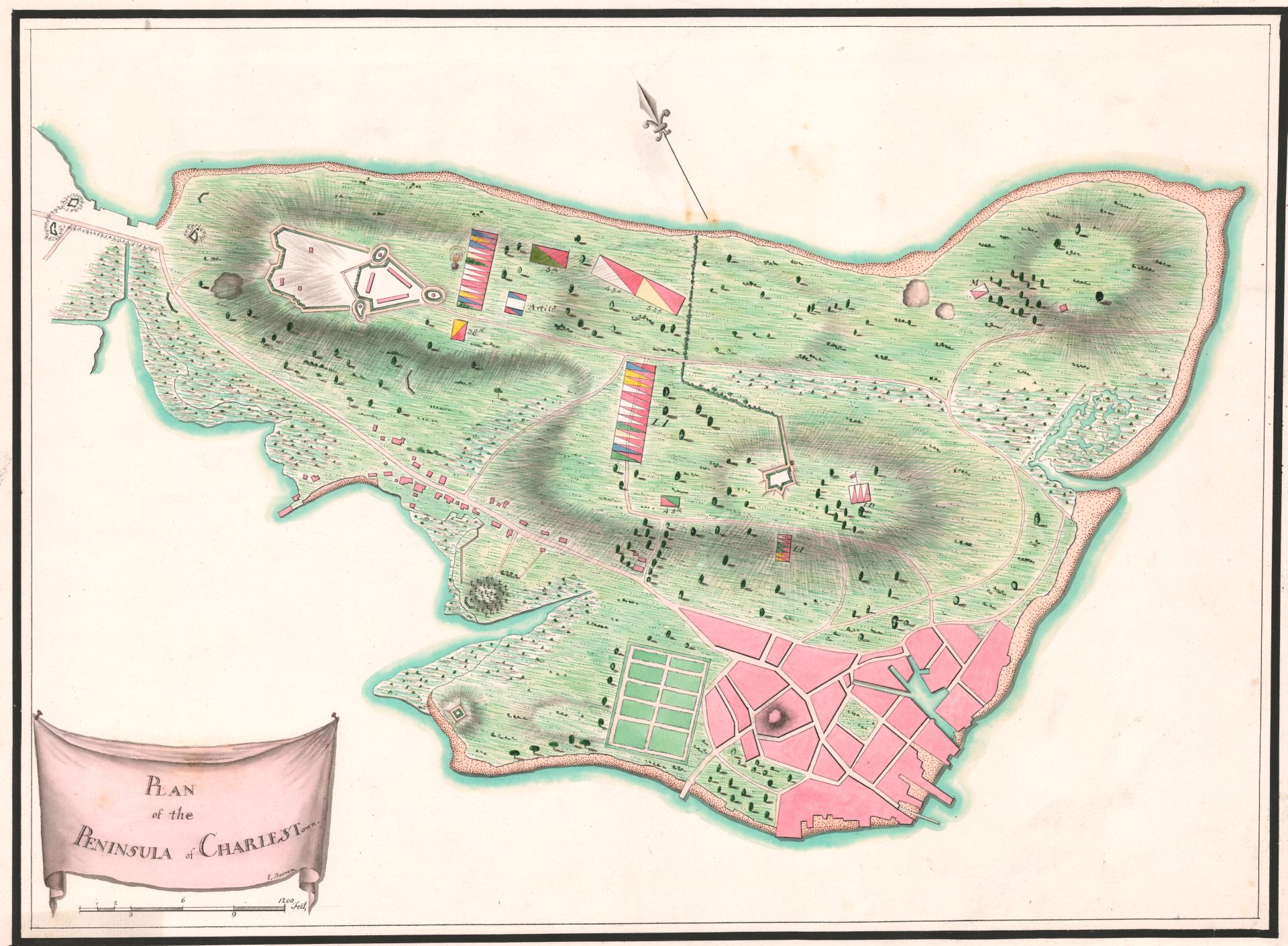

Percy averted an even greater disaster by marching his 1,700 men by an unexpected route. Rather than continuing straight to Cambridge, he took a left turn to head to the Charlestown neck, where the ships of the Royal Navy could protect his force with their guns and ferry him across the Charles River, back to Boston.

For nearly 250 years, the maps lay forgotten in a box with dozens of other maps of Revolutionary war battles and encampments brought back by Gen. Percy. As the son of the First Duke of Northumberland, he was heir to Alnwick Castle, one of the oldest castles in England. Today the castle welcomes half a million visitors a year, having gained in popularity after serving as a filming location for the Harry Potter movies.

In the Sixties, an earlier team from American Heritage had discovered and catalogued the maps. Chris Hunwick, curator of collection today, told us they still used the catalogue developed at the time by William and Elizabeth Cumming, who wrote about their find in our August 1969 issue.

Who was the man who amassed this extraordinary collection of maps? David Hackett Fischer described Percy in his book, Paul Revere's Ride:

Lord Percy came by his sympathies for the colonists naturally. His father had voted against the Stamp Act in Parliament, and Percy himself was skeptical about the Crown's handling of the colonial discontent.

The letters in Alnwick Castle provide a fascinating look into the perspective of the British leadership early in the Revolution. Percy had left for his posting in Boston in April of 1774. While waiting at a harbor in Ireland for his troops to catch up, he wrote to a friend that he had been given command of eight regiments. “I fancy severity is intended,” he worried. “Surely the People of Boston are not Mad enough to think of opposing us.”

An hour after arriving in Boston on July 5, 1774, Percy wrote his father that, “I have the misfortune, for I must think it so, of commanding the camp here. The people, by all accounts, are extremely violent & wrong headed, so much so that I fear we shall be obliged to come to extremities.”

A few months later, he worried in a letter to a friend that, “Our affairs here are in the most Critical Situation imaginable; Nothing less than the total loss or Conquest of the Colonies must be the End of it. Either indeed is disagreeable, but one or the other is now absolutely necessary.”

Matters grew even worse after colonials dumped tons of tea in Boston harbor in December. On April 8, 1775 Percy reported to his cousin that, “Things now every day begin to grow more & more serious.” He hoped that the recent addresses in both Houses of Parliament had “convinced the Rebels (for we may now legally call them so) that there is no hopes for them but by submitting to Parliament; they have therefore begun seriously to form their Army & have already appointed all the Staff.”

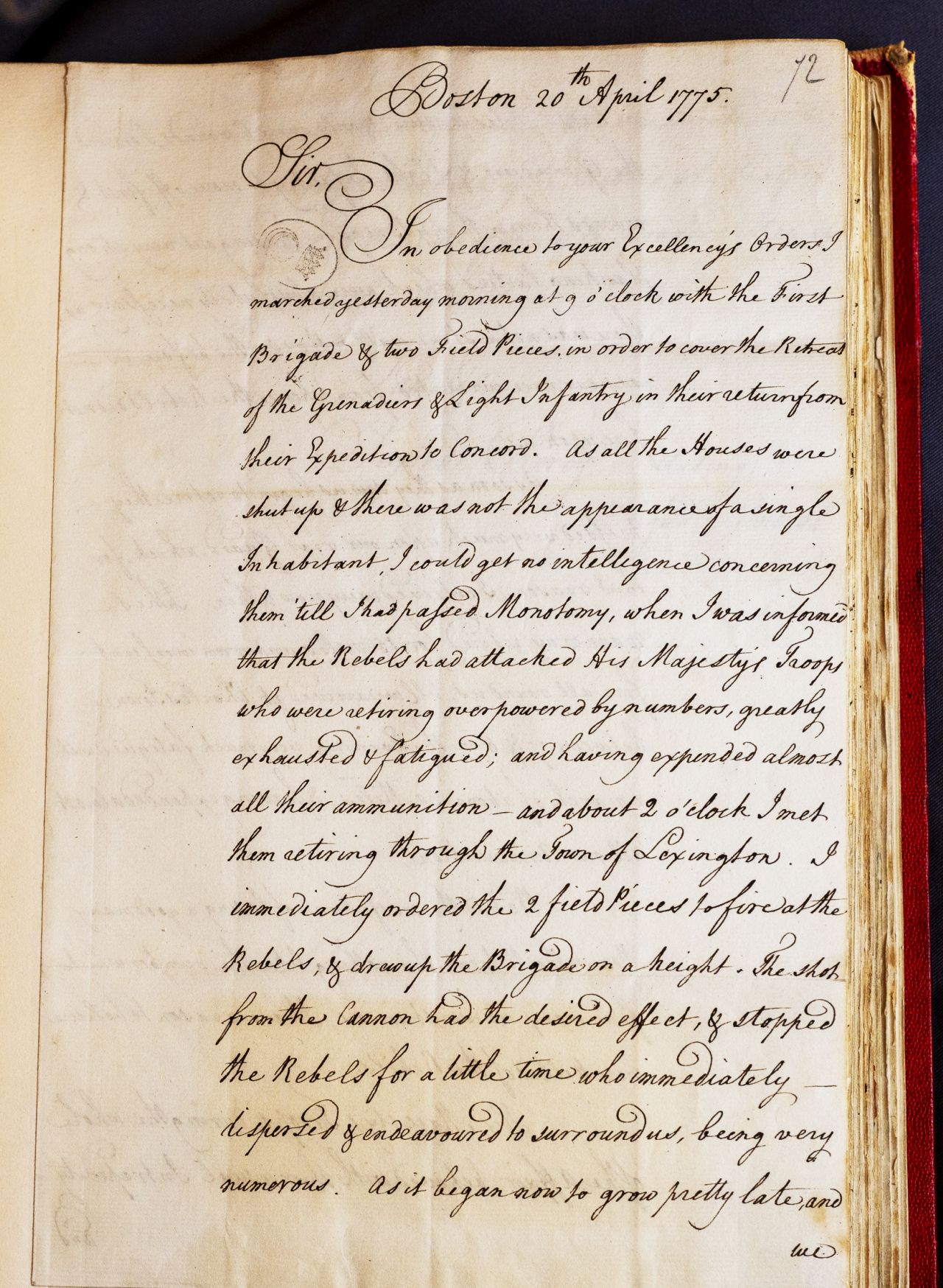

Nine days later, Percy would find out how serious the rebels were. Among the treasures in Alnwick Castle is a handwritten copy of Percy's report to his superior, Governor Gage, commander-in-chief of the British forces in America at the time. On April 20, the day after the battle, Percy wrote,

The refusal of the rebels to fight a traditional European-style battle greatly frustrated the British. “There was not a stone-wall, or house... from whence the Rebels did not fire upon us,” he told Gage.

Later that day, Percy wrote to his friend, General Harvey, adjutant general in London. “Whoever looks upon them as an irregular mob, will find himself much mistaken.”

The Americans, he observed, “have men amongst them who know very well what they are about, having been employed as Rangers agst the Indians & Canadians, & this country being much covd w. wood, and hilly, is very advantageous for their method of fighting.”

Percy's rescue of Col. Francis Smith's panicked troops retreating from Lexington averted what could have been a much worse disaster. But still the British forces that day suffered an estimated 73 killed, 174 wounded, and 53 missing.

For the next two years, Hugh Percy would serve his King honorably, fighting the rebels at Newport, Long Island, and other clashes. He led the British forces in their attack on Fort Washington, capturing nearly 3,000 Americans and dealing them the worst defeat of the war.

Despite his promotion to lieutenant general in 1777, Percy resigned and left the Colonies, provoked by the new commander-in-chief General William Howe and frustrated with the way the British generals were conducting the war.

Returning to England, Percy remarried, had nine children, and inherited the family’s titles and land in 1786. He spent the rest of his life overseeing his vast properties and trying to improve life for the tenants and farmers. He took command of the Percy Yeomanry Regiment in 1798 when Napoleon threatened to invade.

Percy died suddenly in July 1817 from the “rheumatic gout” that had plagued him in his later years. The old general was buried in the Northumberland Vault in Westminster Abbey.