Recent rehabilitation of this important site at the Gettysburg battlefield provides a much improved experience for visitors.

-

Fall 2025

Volume70Issue4

In one of the most dramatic moments of the Civil War, Union soldiers at the battle of Gettysburg rushed up Little Round Top just ahead of Confederate troops who had the same idea: capture the position that commanded a view of nearly the entire battlefield where 165,000 men were struggling to kill each other.

Earlier that afternoon, at about 3:30 PM, Gen. G.K. Warren, chief engineer of the Union army, had climbed the hill and was shocked when he saw the position was largely undefended. Confederate troops were moving forward from woods just below him. If the rebels seized Little Round Top, they could outflank the line of Union troops that stretched for two miles north along Cemetery Ridge.

“I saw that this was the key of the whole position,” Gen. Warren wrote later.

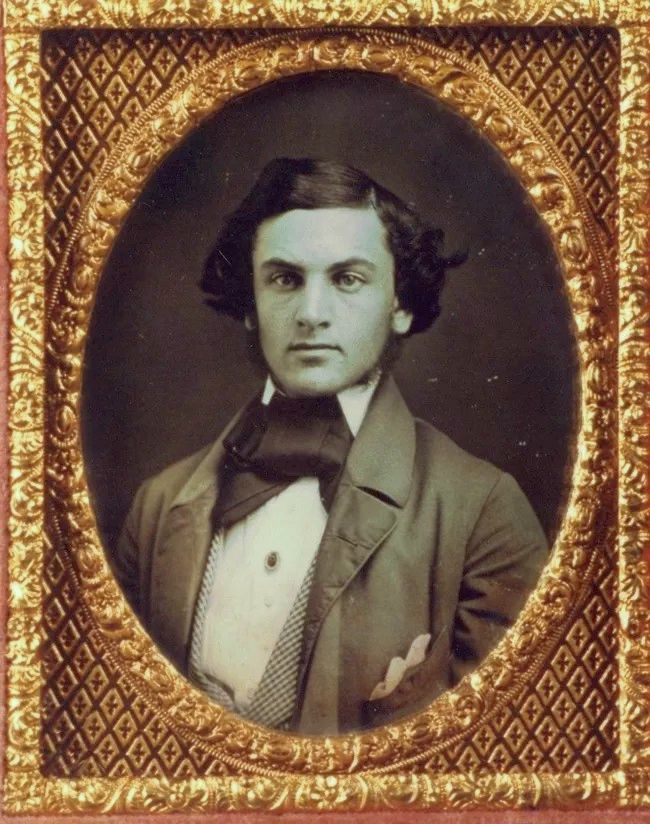

An officer sent by Warren encountered a brigade of the 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry and informed them what the general had discovered. Acting without orders, their commander, Gen. Strong Vincent, quickly moved his 1,300 men to the top of Little Round Top. Vincent was a former ironworker who had studied law at Harvard and proven himself in two years of fighting in Virginia. Promoted after his superiors were killed or resigned, he was made brigadier general at the age of 26. Recently married, Vincent wrote his pregnant wife Elizabeth just before the battle that, “If I fall, remember you have given your husband to the most righteous cause that ever widowed a woman.”

Vincent moved his men into position among the rocks as the Confederates approached. When the men on his right flank appeared to be wavering, he jumped on a large boulder and ordered them, “Don’t give an inch!”

One of the regiments under Vincent's command, the 20th Maine led by Col. Joshua Chamberlain, has received much of the fame for the defense of Little Round Top, but there is no doubt that the efforts and bravery of Vincent were critical in the eventual Union victory. Vincent impressed on Chamberlain the importance of his holding the position on the brigade's far left flank.

The 20th Maine withstood attack after attack from the 15th Alabama Infantry until finally, with his men suffering many casualties and running low on ammunition, Chamberland famously ordered a bayonet charge. He and his courageous men stopped the attack, captured 101 Confederate soldiers, and saved the Union's left flank and possibly the battle. Chamberlain was later awarded the Presidential Medal of Honor, elected governor of Maine, and served as president of Bowdoin College.

Around this time further north on the hill, Gen. Vincent was badly wounded. He was heard to say, “This is the fourth or fifth time they have shot at me, and they have hit me at last.” Vincent was carried to a nearby farm where he passed away five days later.

In recent years, Little Round Top has suffered from its popularity. Large crowds of visitors were impacting the site, signs and trails were confusing, and extraneous trees and vegetation blocked the view. Many “social trails,” the pathways through bushes and off the authorized trails, were marring the site and causing erosion.

The National Park Service closed the area for nearly two years to undertake a major rehabilitation, aided by the Gettysburg Foundation, American Battlefield Trust, and National Park Foundation.

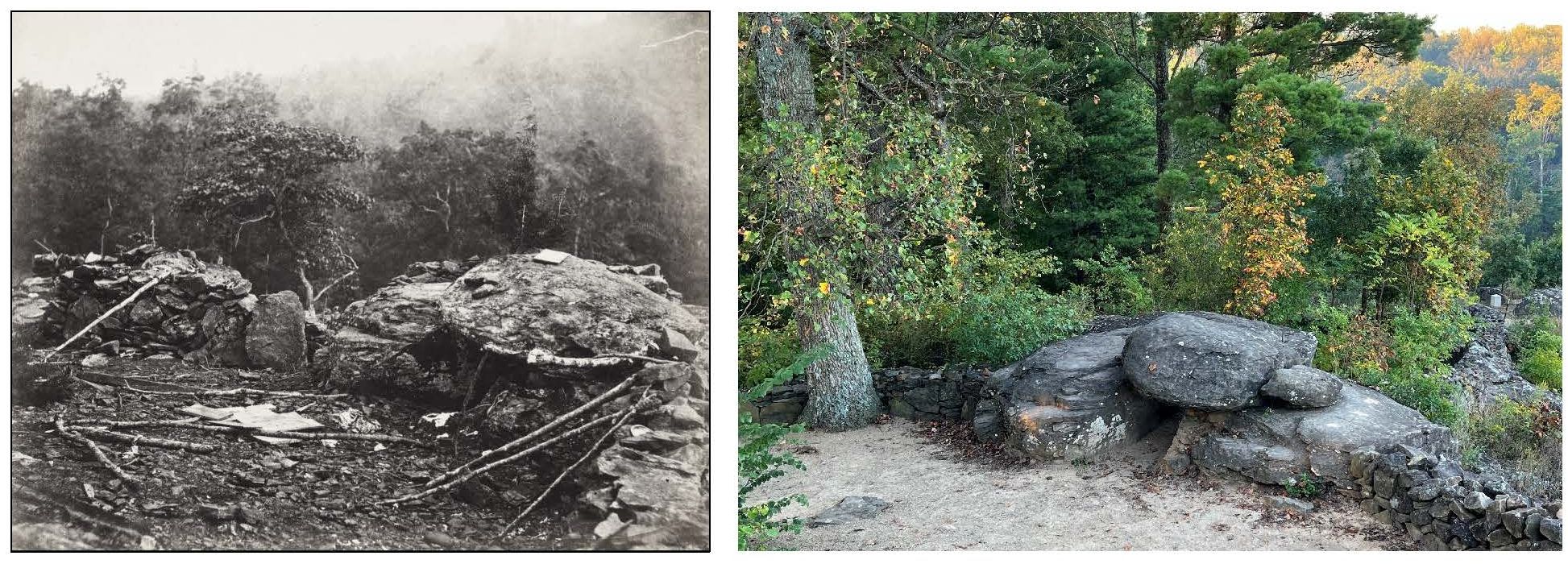

The $12.9 million project addressed problems with parking, accessibility, erosion, and vegetation. Key improvements included stabilizing trails with durable, locally sourced aggregate, reconstructing breastworks, improving visitor access to monuments, and adding new interpretive wayside signage, all while aiming to restore a more natural, forested appearance to the site.

Monuments were cleaned and protected, and the landscape restored to be more like its Civil War appearance, including rebuilding breastworks with original stones and re-establishing forest cover. Workers removed excessive concrete and granite and created a more of a natural, wooded appearance by planting native grasses and trees.

The project also added 19 interpretive exhibits. The attractive and informative new signs help visitors connect with the historical significance of the site.

Years after the battle of Gettysburg, Joshua Chamberlain observed that, “In great deeds something abides. On great fields something stays.”

There are few places where the power of place can be felt so keenly as Little Round Top, and we owe a vote of thanks to NPS and its partners for the good work they did in making that possible.