Since her untimely death in 1963, the legendary country music star—and the first female to be inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame—continues to inspire new audiences and artists.

-

Fall 2025

Volume70Issue4

On August 21, 1961, Patsy Cline hobbled into producer Owen Bradley’s Nashville studio to record a new song written by an up-and-coming songwriter named Willie Nelson. Just two months earlier, Cline had been thrown through a windshield in a horrific car crash. She was left with a dislocated hip, broken bones, and a deep gash across her forehead. After over a month in the hospital, she was still sore, often short of breath, and walking with crutches. Cline’s gift for song was undeniable, but it was her grit—matched by few in country music—that carried her forward. Both were on full display in the studio.

At first, she struggled with Nelson’s famous phrasing, finding it unique and impossible to emulate, and her injuries made the high notes difficult to reach. That day, she managed only to record the backing track. But then, when she came back to the studio on September 15, something had shifted. Cline stopped trying to mimic Nelson’s demo and let her own aching, tender voice take over. With one raw and emotional take, she sealed “Crazy” into music history. Surrounded by Nashville’s finest musicians and backed by The Jordanaires, the song sold millions. More than that, it lifted Cline into an entirely new stratosphere as an artist.

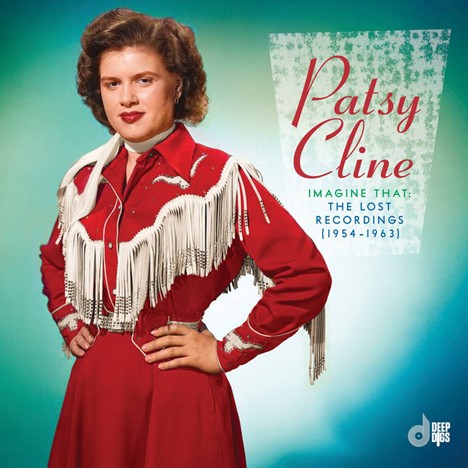

Every note that Cline ever sang carried heartache, longing, and resilience. She captivated audiences in a way few artists have. Years after her death in a plane crash in March 1963, Cline’s legacy was reintroduced to new generations in 1980, when Loretta Lynn’s biopic Coal Miner’s Daughter featured Beverly D’Angelo’s convincing portrayal of Cline. Five years later, she became the focus of her own biopic, Sweet Dreams, with Jessica Lange bringing her story to life. In the decades since, her records have continued to sell, and her influence has shaped country music. In 2025, the release of Imagine That: The Lost Recordings once again proved why she remains the gold standard for female country artists.

Cline’s unyielding resolve was forged in early childhood hardships. Born Virginia Patterson Hensley on September 8, 1932, in the small town of Winchester, Virginia, she was the first child of Hilda Virginia Patterson Hensley, then just 16, and Samuel Hensley, a 43-year-old blacksmith. Her childhood, while not entirely unhappy, was marked by constant upheaval. Her parents’ turbulent marriage and her father’s frequent job changes kept the family in a near-constant state of relocation. By the time she was 16, they had moved 19 times.

While her father worked as a boilerman at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Cline would listen to the big bands playing on campus, and she spent hours trying to mimic the girl singer. During her early teens, Hilda and Sam separated, and Hilda returned to Winchester, where she rented a home and raised Patsy, Samuel Jr., and Sylvia on her own. Seeing her mother’s immense responsibilities and hardships, Cline left school to work and help support the family.

Searching for ways to make money, the teenager turned to singing. In the mid-1940s, country-western music was not popular in Winchester, but Joltin’ Jim McCoy had a country radio show that aired every Saturday. Cline made sure to tune in religiously. One day she walked into his office and asked to perform on the radio program. After a quick audition, he hired her as a weekly singer. Soon after, she began performing popular country and pop tunes at local bars and supper clubs.

In the years that followed, Cline took on whatever work she could find—slitting chickens’ necks at a meatpacking plant, cleaning Greyhound buses, and helping out at a local drugstore—but her passion was always singing. She steadily built a reputation through radio and local television appearances, and in 1948 she traveled to Nashville to perform on Roy Acuff’s WSM-AM Dinner Bell radio program. Back home in Winchester, Cline joined bandleader Bill Peer and his group the Melody Boys.

Hilda recognized her daughter’s talent early on and wholeheartedly supported her ambitions. The two shared a bond so close that, as Cline’s daughter Julie Fudge remarked in a recent interview, they were more like sisters than mother and daughter. Hilda was her fiercest champion, always driving her to performances and handcrafting elaborate Western outfits that awed audiences. The painstakingly made ensembles rivaled the glamorous designs of famed tailor Nudie Cohn. Stars like Hank Williams, Little Jimmy Dickens, and Porter Wagoner wore his creations. Cline understood that image carried power, and even with little money, she was determined to look every bit the star she dreamed of becoming.

In 1953, Patsy married Gerald Cline, whose family ran a prosperous business. She longed for the stability the marriage seemed to promise, but it quickly became clear that their visions for the future were at odds. Gerald wanted a conventional wife and had no interest in having children, while she dreamed of both a family and a singing career.

Determined to push forward with her music, in 1954, she signed with Four Star Records under Bill Peer’s management. The contract, however, was stacked against her. Cline earned only 2.34 percent of profits and was restricted to recording songs from the label’s publishing catalog. This was a setup designed to benefit Four Star’s owner far more than its artists. Soon after, Four Star struck a leasing and distribution deal with Decca Records, giving Decca control over her recording sessions and the power to choose her producer.

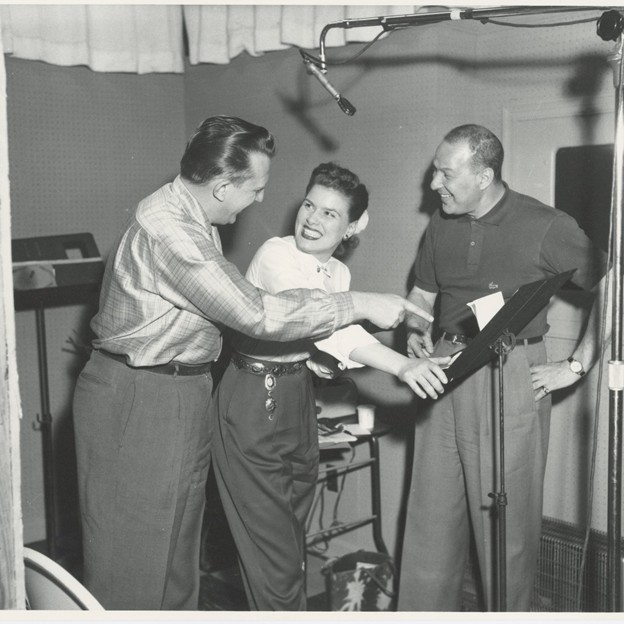

Decca executive Paul Cohen initially brought in producer Owen Bradley to help with Cline’s recordings, and when Cohen left the label’s country division in 1958, Bradley became her full-time producer. Cline’s first release under her new contract, “A Church, a Courtroom, and Then Goodbye” (1955), fell flat commercially, but Bradley saw something in her that Four Star never had. He recognized not only her potential but also her relentless drive, and he was ready to give her the time and attention she had long been denied.

Cline involved herself in every stage of the recording process, from lyrics to final takes. On two Four Star recordings cut in New York in April 1957— “A Stranger in My Arms” and “Don’t Ever Leave Me Again”—she was even credited as a songwriter under her given name, Virginia Hensley. Though not a prolific writer, she was never shy about speaking up to adjust a word or reshape a phrase to make a song feel authentic to her.

Bradley recognized Cline as a powerhouse vocalist with extraordinary range, but he also knew her style did not sit neatly within traditional country. Influenced by pop singer Kay Starr, her voice carried a smooth, polished tone that sounded more at home in New York’s studios than Nashville’s honky-tonks. By the late 1950s, however, the music world was shifting. Rock ’n’ roll was dominating the charts, and Cline’s rhinestone Western outfits and material were beginning to feel dated. Her records struggled to gain traction, and it was clear that the genre itself needed to evolve.

Bradley and other leading Nashville producers began reshaping country music into something new: the Nashville Sound. They swapped steel guitars for lush string arrangements and added sophisticated harmonies from groups like The Jordanaires and the Anita Kerr Singers. It was smoother, more cosmopolitan, and it offered Cline the perfect setting to showcase her unique blend of power and polish.

With her refined sound, Cline put aside her Western “Patsy Montana–style” outfits for a sleek cocktail dress when she appeared on CBS’s Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts in January 1957. There was one problem: the rules of the show barred family members from serving as a contestant’s talent scout. Her mother, Hilda, was set to fill that role, and rather than step aside, the two were determined to find a way. Quietly, they worked around the obstacle, and because their last names differed, they slipped through unnoticed.

That night, Cline delivered a riveting performance of “Walkin’ After Midnight” and won the competition. With her prize money, she paid off her mother’s mortgage in Winchester, and when the song was released as a single, it raced up the pop and country charts, marking Cline’s first big breakthrough.

As her career finally began to find its footing, her marriage to Gerald Cline unraveled, and by 1956, the two went their separate ways. That same year, she met 22-year-old Charlie Dick. He was lively, fun-loving, and carried a toughness shaped by his own hardships. Like Cline, he had grown up without a father and left school early to help his mother make ends meet, and the two quickly connected over their shared love of music. In the fall of 1957, Cline and Dick married in a small ceremony at Hilda’s home.

Her performance on Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts had introduced Cline to millions, and audiences were eager to hear more. In 1958, she released several Decca singles, including the easy-going “Come On In” and the spiritual ballad “Dear God.” None managed to chart, but that year still brought joy with the birth of her first child, Julie, in August. The following year, with the help of Charlie’s military checks, the young couple finally had enough money, and it was time to chase her dreams in earnest. They moved to Nashville, determined to make her ambitions a reality.

When Cline arrived, Nashville’s music scene was still very much a man’s world. Women were expected to play supporting roles rather than headline their own shows. Kitty Wells had broken barriers with “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels” (1952), but even she stayed within the industry’s limits for female performers. Cline was different. Years of struggle had given her a fierce self-assurance, and she refused to be pushed aside. She had fought too hard to let any manager or record label dictate her future.

Artist Mandy Barnett, who later portrayed Cline in the musical Always…Patsy Cline, put it simply: “She wasn’t just along for the ride—she knew what she wanted, and she made it happen, which was rare for women in country music at that time.” In a male-dominated industry, Cline spoke out for equal pay, demanded respect, and supported other women finding their place. She encouraged friends like Loretta Lynn and Dottie West, proving that her success was never just about herself.

Even after establishing herself in Nashville, Cline remained in a discouraging business arrangement with Four Star. It had been three years since her last hit, and as guitarist Harold Bradley later admitted, “Ninety percent of the records we made with her were flops. The songs were not good, and they were trying to make them into something better than what they were.” Cline kept busy with Opry appearances and package tours, though the constant travel often pulled her away from her family.

By January 1960, her contract with Four Star had ended, and she was free to pursue a new deal. With new manager Randy Hughes guiding her, she wasted no time approaching Bradley at Decca, asking for $1,000 to start fresh. Bradley readily agreed. That same year, she also realized a lifelong dream when she became a member of the Grand Ole Opry. After years of pushing and trying, Cline’s career had turned the corner.

She worked seamlessly with Bradley at Decca, and for the first time, she was surrounded by songwriters who believed in her. Rising talents like Harlan Howard, Hank Cochran, and Willie Nelson were eager for her to cut their material, knowing she had the rare ability to take a lyric and live inside it. “She had this incredible way of making every song feel personal, like she was living in it, not just singing it,” said Barnett. “She was also able to be both tough and vulnerable at the same time, which is part of what makes her music timeless.”

That blend came through in “I Fall to Pieces” (1961), written by Howard and Cochran. At first, Cline was not eager to record it, and when the single was released, it struggled to gain much traction. But slowly, it climbed the charts. In the studio, Bradley had paired her with The Jordanaires to give the song the polish of the Nashville Sound. Cline worried their vocals might overwhelm hers, but Bradley urged her to trust him. The result was a smooth balance, with her voice being front and center, lifted by harmonies that only magnified the ache in the song.

The June 1961 car accident had nearly ended Cline’s life and career, but in August, she was back on the Opry stage and in the studio recording “Crazy.” At home, she and Charlie Dick operated as a team, with Dick caring for their children, which now included son Randy, while also helping steer her career. When Dick first heard Willie Nelson’s demo of “Crazy,” he immediately knew it was the perfect fit for his wife. Released in October, the single shot into the top ten on both the country and pop charts and went on to become the most-played jukebox song of all time.

Cline’s momentum only grew in 1962. In January, Hank Cochran’s “She’s Got You”—a fusion of jazz-pop styling and country heartache—hit number one on the country charts. She sold out concert halls, toured tirelessly, and made history as the first female country artist to headline Las Vegas with a 35-night run at The Mint Casino. The family traveled together, and daughter Julie later recalled the thrill of riding llamas during their time there. With Cline at the forefront and the Nashville Sound reaching a wider audience, country music was once again in the mainstream spotlight.

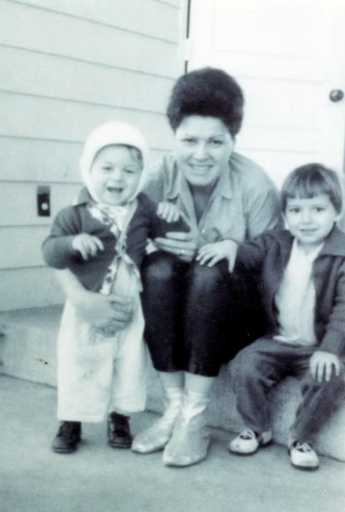

For the second year in a row, Cline was voted the most popular female singer in country music. That summer, she traveled to Los Angeles to appear at the Hollywood Bowl alongside Johnny Cash. Her resolve had carried her from smoke-filled bars to making history on some of the world’s most celebrated stages, a journey that underscored just how far she had come. Back in Tennessee, she and Dick settled into what they proudly called their “dream home” in Goodlettsville. Behind the spotlight, life there was ordinary for the family. Julie remembers her mother unwinding with crayons and coloring books, keeping one for herself while setting aside a Barbie-themed version for her daughter.

Unfortunately, Cline’s happiness at home was brief. In March 1963, she performed at a benefit concert in Kansas City. Just two days later, the plane carrying her back to Nashville crashed near Camden, Tennessee, killing Cline, her manager and pilot Randy Hughes, along with fellow Opry stars Cowboy Copas and Hawkshaw Hawkins. The news sent shockwaves through Nashville and beyond. She was laid to rest in her hometown of Winchester. An estimated 25,000 mourners gathered to pay their respects.

On April 15, “Sweet Dreams”—the haunting ballad Cline had performed at her final concert in Kansas City—was released and climbed to number five on the country charts. Later that year, she returned to the top 10 with her recording of Bob Wills’s “Faded Love.” In 1967, Patsy Cline’s Greatest Hits was issued, and it went on to become one of the best-selling albums by a female country artist, surpassing 10 million copies and remaining on the charts for an astonishing 722 weeks.

Charlie Dick became the guardian of his wife’s music, overseeing new releases and working to introduce her songs to new generations until his passing in 2015 at the age of 81. And in 1973, Cline’s influence was formally recognized when she became the first solo female artist inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame, cementing her place as one of the genre’s defining figures.

Cline’s story continues to be carefully carried forward by those who knew her and by the many still moved by her music. Today, her daughter Julie Fudge serves as Chief Administrative Officer of Patsy Cline Enterprises, working to honor her mother’s memory and dispel the myths that have surrounded her life. Fudge acknowledges that because of Cline’s untimely passing, she has taken on an almost storybook status. “But even so,” she insisted, “her story should be true. The truth is better than any script that can be written.”

The girl from Winchester who once dreamed of hearing her voice on the radio lived to see that dream soar far beyond what she imagined. “I have gotten more than I asked for,” she once said. “All that I ever wanted was to hear my voice on record and have a song among the Top 20.” Instead, she carved her place in history.

Like that day in 1961 when she limped into Bradley’s studio on crutches—bruised, battered, but unwilling to let pain silence her—Cline met every challenge head-on. She broke barriers, demanded respect, and opened doors for artists from Loretta Lynn, Dolly Parton, and Reba McEntire to today’s artists Kacey Musgraves and Mickey Guyton.

“She was real,” said Fudge. “Her voice was a natural, beautiful voice. She was honest. She was bold. And she has become legendary, almost mythical.” Cline turned hardship into art and sorrow into song. Her recording of “Crazy”—enshrined in the Grammy Hall of Fame and the National Recording Registry—remains one of the most celebrated country songs of all time. Her music still soars, a testament to the grit, grace, and voice that secured her place as one of the most legendary figures in American music history.