Two hundred years ago, the conflict in which the U.S. seized the Deep South from its Native inhabitants was a turning point in American history, but it is largely forgotten today.

-

Winter 2024

Volume69Issue1

Editor’s Note: One of the most respected historians of the Civil War and America’s westward expansion, Peter Cozzens has written 17 books and recently published the third volume of his trilogy about the Indian wars in the United States. This essay consists of vignettes adapted from A Brutal Reckoning: Andrew Jackson, the Creek Indians, and the Epic War for the American South. The previous two books in the trilogy looked at the wars in the Old Northwest and the American West. The latter book, The Earth Is Weeping: The Epic Story of the Indian Wars for the American West, won the Gilder Lehrman Prize for Military History.

The War of 1812 was going badly for the United States in the summer of 1813. British forces menaced the Eastern Seaboard and had repelled American attempts to seize Canada. There were rumors of planned Indian uprisings west of the Appalachians, perhaps abetted by the British.

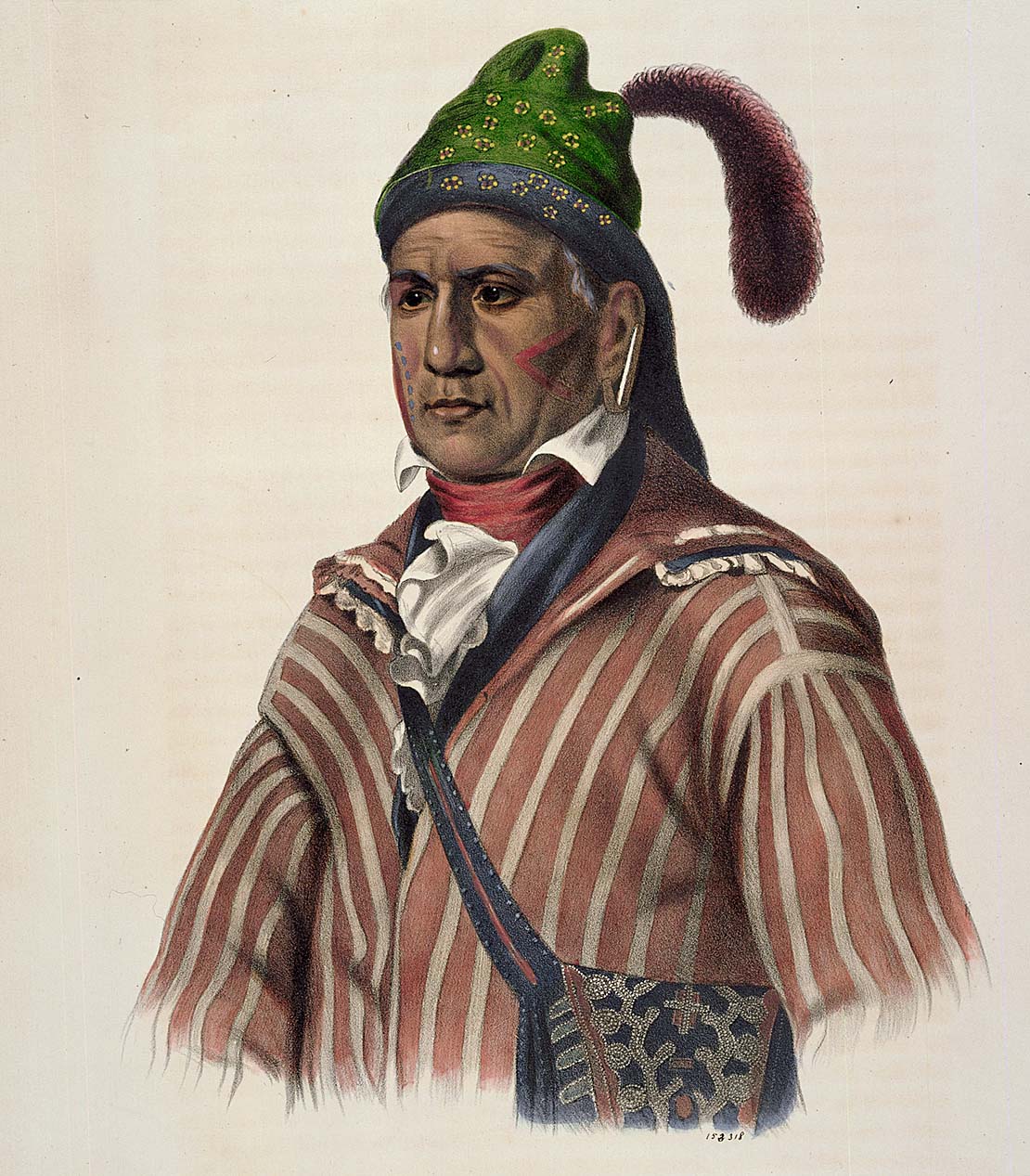

Those reports would soon prove true, and the horrific combat that followed would end up largely eliminating the Indian presence in the Deep South. A dispute that began as a civil war among Creek (Muscogee) factions became a ruthless struggle of the Native population against American expansion. Not only was the Creek War the most pitiless clash between American Indians and whites in U.S. history, but the defeat of the Red Sticks — as those opposed to American encroachment were known because of the red war clubs they carried — also cost the entire Creek people as well as the neighboring Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Cherokee nations their homelands.

No other Indian conflict in our history so changed the complexion of American society as did the Creek War. The collapse of Red Stick resistance in 1814 led inexorably to the Indian Trail of Tears two decades later, which opened Alabama, much of Mississippi, and portions of Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee to white settlement. That, in turn, gave rise to the Cotton Kingdom, without which there would have been no casus belli for the American Civil War.

White provocations in Creek territory were considerable. Poor Georgians of limited prospects, with boundless hatred of Indians, and undisguised scorn for government treaties were naturally drawn to the frontier. In the spring of 1794, an armed rabble built stockades on the west bank of the Oconee River border and declared themselves an independent nation. Georgia militiamen defied their governor and struck deep into the Creek confederacy.

President Washington knew that treaties alone, no matter how honestly negotiated, offered only a brief respite from the intermittent violence. He had advocated a policy of fair, government-regulated trade with the Indians, supplemented by a program to promote their “civilization” – in other words, to convert them into American-style small farmers. But few Creek men favored abandoning the hunt in favor of ranching and planting, traditionally the work of women.

A divide increasingly grew between the Lower (or eastern) Creeks, who tended to accept farming, and the Upper (or western) Creeks, who resented the Georgian despoliation and the spread of cattle and hog ranching and cotton farming on their lands.

See “Tecumseh and The Prophet at Tippecanoe” By Peter Cozzens

In 1811, the Shawnee war chief Tecumseh, co-leader with his brother Tenskwatawa (the Prophet) of a vast Northwestern Indian alliance, visited the Creeks. Tecumseh urged them to join his pan-Indian alliance. He said that the Prophet promised that the ‘‘Master of Life had taken pity on his red children and wished to save them from destruction,” provided they return to communal living. Indians who accumulated “wealth and ornaments” would “crumble into dust,” but those who shared their possessions with fellow believers would die happy.

The Master of Life (or, as the Creeks knew him, the Master of Breath) insisted that the Indians shun the Americans, who were the by-products of the foam and scum that rolled onto the coast of the Great Salt Lake (the Atlantic Ocean), usurpers of Indian land despised by the Master of Life.

The Shawnee Prophet said further that the Master of Life “in his wrath would assist the Indians in the recovery of their lands and country, which he had made on purpose for their special use.” Most Creeks initially rejected the Shawnee brothers’ appeal, but it took hold with the growing faction of militant traditionalists known as the Red Sticks. A Creek civil war ensued, and war with the American interlopers appeared inevitable.

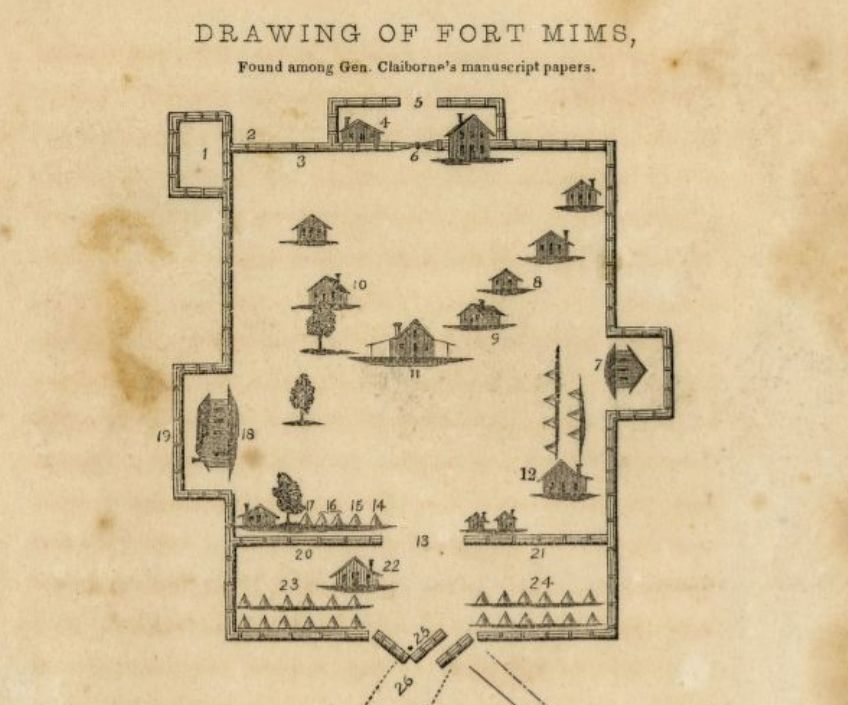

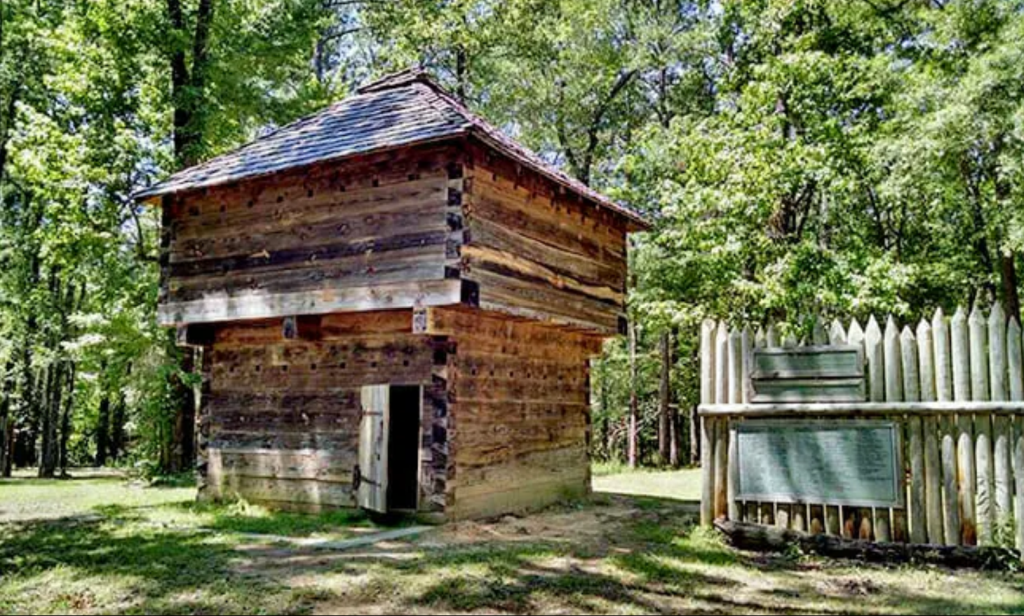

Massacre at Fort Mims

By the summer of 1813, threats of Red Stick attacks led white and mixed-race (métis) settlers and militia on the western fringe of the Red Sticks country to construct wooden stockades and blockhouses near settlements, and many families sought protection in those fortifications. On August 30, at the hastily constructed Fort Mims, about forty miles north of present-day Mobile, Private Nehemiah Page of the Mississippi Territory Volunteers woke up in his tent with a hangover as first light washed the eastern sky above the forest. As drummers beat reveille into his throbbing skull, everywhere he looked, there were people – 400 men, women, and children packed inside the one-and-a-quarter-acre stockade.

Private Page had gotten drunk the night before to celebrate the completion of the fort’s only blockhouse. It was not much of an achievement, but it provided as good an excuse as any for the 28-year-old militiaman and his comrades to drink.

On his way to roll call, he passed teeming settlers, slaves, and scampering dogs, then fell into a straggling line of 146 volunteers and local militiamen. Slapping at the swarming mosquitoes, he declared himself present. Then, he staggered outside the open eastern gate and dropped down to sleep in one of Sam Mims’s stables. There were no drills scheduled that day and no patrolling or sentry duties.

As the sun climbed higher, the heat and humidity rose apace, and the fort’s commander, Major Daniel Beasley, did nothing to animate the garrison. Unlike Private Page, who merely nursed a morning hangover, Beasley was drunk. With a bottle by his side, he composed a rambling letter to his commanding general complaining of the unreliability of the militia, but bragging that he had “improved the fort and have it much stronger than when you were here.” As for the rumored Red Sticks, the soldiers were “anxious to see them.”

The morning dragged on. At 11:00 a.m., Beasley directed a drum beat to summon the fort’s tenants to witness the punishment of a slave who had dared to claim that he had seen Red Sticks in the woods. Soldiers and families gathered about the whipping post. Someone struck up a fiddle. The unfortunate young man embraced the post and awaited the lash strokes. Drummers lifted their drumsticks.

Pounding horse hooves interrupted the flogging. Drawing rein at the fort’s east gate, James Cornells shouted to Major Beasley that he had just seen a dozen warriors in the woods, evidence enough that the long-feared attack on Fort Mims was at hand. The befuddled Beasley waved Cornells off; he must have “only seen a gang of red cattle.” To which the incredulous man replied, “That gang of red cattle would give him a hell of a kick before night.” Fuming, Beasley stammered an order for his immediate arrest. Cornells galloped away in disgust, the drums beat, and the lash cracked on the unfortunate boy’s bare back.

In a ravine just east of Fort Mims, 730 Red Stick warriors rose in unison from a tangle of cypress and tupelo-gum trees and surged toward the fort. The rhythmic tramping awakened Private Page. Peering through a gap in the stable’s hewn logs, he glimpsed a sobering sight – hundreds of men, painted black, red, or a mix of red and black, each stripped to his loincloth, from the back of which dangled a severed cow’s tail. Some warriors carried muskets, others bows and arrows, but all brandished the distinctive curved, red war clubs of the Red Sticks. Their moccasin-muffled footfalls growing firmer, they dashed past Page to cover the final hundred yards to the open east gate. The lone sentry, intently watching a card game, had his back to the attackers.

The instant the last Indian passed the stable, Private Page sprang out and ran toward the Alabama River. He never looked back.

Thirty yards separated the sprinting warriors from the east gate before a startled sentry discharged his musket and darted into the tent-filled ground occupied by Mississippi Territory Volunteers. Recumbent or seated, the unsuspecting volunteers struggled to their feet. Most of their muskets were unloaded; many were stacked carelessly about the yard. Sword in hand, a suddenly lucid Major Beasley shoved his way toward the gate. A Red Stick war club ended his effort, and he slumped to the ground, having achieved the heroic demise he desired.

War whoops, musket fire, the screams of frightened women and children, and the yelping of dogs blended in a terrifying cacophony. Gun smoke hung low and thick in the humid air. Although the Red Sticks owned most of the outer wall, too few warriors entered the fort to decide the struggle. At 3 p.m., the Red Sticks withdrew several hundred yards to tally their losses and decide their next move.

Later that afternoon, the battle resumed with greater fury. Warriors cut a jagged hole in the split-pine posts along the southern wall. They shot flaming arrows through the gap toward the Mimses’ kitchen and smokehouse. Both caught fire. A wind sprang up. Blowing embers set the house ablaze. “Then it was,” recalled the surgeon Dr. Thomas G. Holmes, “that horror and dismay was to be seen in every face in the fort.”

With boundless bloodlust, Red Sticks cut down fleeing settlers in their tracks. “The way that many of the unfortunate women were mangled and cut to pieces is shocking to humanity, for many of the women who were pregnant had their unborn infants cut from the womb and lay by their bleeding mothers,” Dr. Holmes remembered. All the women, he continued, “were stripped of every article of clothing; not satisfied with this,” the Red Sticks “scalped every solitary one, taking the skin of the whole head so as to make many scalps.”

Starting a bonfire, warriors tossed both the dead and the wounded into the flames. There were occasional acts of kindness amid the carnage. When the Mimses’ house went up in flames, the métis (or mixed-race) teenage Susan Hatterway, whose white husband lay dead, took a four-year-old métis girl in one hand and a black slave girl in the other and said to them, “Let’s go out and be killed together.” To Hatterway’s amazement, no one molested them. On the contrary, one bloodstained, begrimed, and war-paint-covered warrior beckoned anxiously to her. She recognized him as a family acquaintance. Claiming the three as his prisoners, the compassionate Red Stick eventually took them to Pensacola, where he turned them over to mutual friends.

By 5:00 p.m., the Battle of Fort Mims – and the subsequent Red Stick massacre of noncombatants – was over. No one can say with certainty how many perished that day. The death toll among the fort’s occupants was likely between 250 and 300. The Red Sticks spared at least half of the slaves, to be placed in Creek bondage, sold, or adopted. Red Stick dead probably numbered at least 100. Regardless of the precise total, they suffered significant losses. The war party quit the smoldering ruins of Fort Mims, made camp in the surrounding forest, and started for home at sunrise the next day, plundering neighborhood plantations on the way.

The gunfire from Fort Mims had been plainly audible at Fort Stoddert, perched on a bluff above the Mobile River about seven miles away. Watching smoke rise on the horizon, Judge Harry Toulmin held Major Beasley’s buoyant morning letter in his hand. A week later, armed with the lurid tales of survivors, he wrote General Ferdinand Claiborne the obvious conclusion: “The massacre at Mims will long, I trust, prove a useful lesson to the people of this country. It will teach them in language of awful solemnity that courage without caution is of little avail.”

Elsewhere in the territory, the families of Ransom Kimbell and Abner James had quit the stifling confines of Fort Sinquefield for the cooler and roomier Kimbell cabin a few miles from the post, though they were aware of the danger. At 3:00 p.m. on September 1, Ransom and Abner were standing outside when a Creek war party stormed the cabin. Unable to help, they were forced to leave their families to be slaughtered and make for Fort Sinquefield.

The attack was over in a matter of minutes. Bursting into the cabin with war clubs in hand, Red Stick warriors crushed skulls and scalped the occupants, then vanished. Fourteen mangled bodies bore mute testimony to the butchery.

That night, a cool rain fell. The drops revived a badly wounded daughter of Abner James. Finding her one-year-old son still alive, she hobbled off toward Fort Sinquefield. A burial party discovered them the next morning, shivering in a hollow log.

Sixty people occupied the rectangular palisade near Samuel Sinquefield’s log cabin. Despite the risk of attack, the morning of September 2 found nearly everyone outside the stockade. An oxcart loaded with the Kimbell and James dead had creaked up the trail at dawn. The men hastily interred the corpses, but lingered for a graveside service. Escorted by two or three guards, nearly two dozen women washed clothes at a spring on low ground 275 yards southwest of the main gate. The guards had stopped halfway downhill, seated themselves on a log, and drowsed.

As the mourners dispersed, someone called the grieving Ransom Kimbell’s attention to an odd rustling in the forest, saying, “Look yonder, what a fine gang of turkeys.”

The Red Sticks had chosen excellent camouflage. The approaching gaggle of birds was actually warriors stooped low; their heads encircled with upright turkey feathers and cow’s tails dangling from their shoulders. Unable to catch the burial detail, they whirled toward the women at the spring.

A quick-thinking mounted volunteer gathered the fort’s dog pack, and with the sixty snarling canines, charged the astonished warriors. The dogs grappled with the Red Sticks long enough for all the women to enter the stockade, except for one who, pregnant and exhausted, fainted just short of the gate. An exultant warrior sank a tomahawk into her skull, ripped off her scalp, and slashed open her belly.

More than two hundred miles to the west, panic gripped the Natchez District, and thousands of residents descended on the territorial capital of Washington amid rumors that Red Stick war parties had come within a day’s ride.

In the Tensaw region north of Mobile, General Ferdinand Claiborne saw little hope in resisting the 3,000 Red Stick warriors he supposed lay ready to batter his defenses. He advised Governor Holmes that, without reinforcements “the whole country promises to be destroyed.”

Judge Toulmin also despaired. “I daily look for accounts of fresh attacks and further massacres, and I know no part of the country that will be safe,” he wrote to the governor. “Without immediate and effectual succor from Georgia and Tennessee, the whole country on the waters of the Mobile River will be laid waste and abandoned.”

Judge Harry Toulmin did his best to ensure that the entire nation shared the horror and outrage that gripped the area. A week after the fort’s destruction, he penned a long and graphic letter to a North Carolina editor that dwelled on the slaughter of white women and children.

Reprinted throughout the United States in October 1813, the letter had the desired effect. Fort Mims became a national rallying cry for vengeance against the Red Sticks. Total war was to be the price they would pay – complete and unsparing retaliation.

There was just one catch. The U.S. government had neither the troops nor the inclination to promptly and adequately respond to an Indian conflict on the southern frontier. The 1812 war with Great Britain, now in its second year, had evolved into an exhausting slugfest along the Canadian border in which neither side had gained a clear advantage, and to which both nations dedicated most of their available manpower. A British naval squadron prowled Chesapeake Bay and terrorized towns on the eastern shores of Maryland and Virginia, but failed in its goal of diverting American forces from Canada.

The American settlers living in the areas west of the Appalachians, primarily the Tennessean militia under generals Andrew Jackson and John Coffee, would largely be on their own to confront the Red Sticks, and, over the next six months, would fight half a dozen major battles against them. Usually, they fought together with Cherokee and Lower Creek allies, including Chief William McIntosh, the son of a Scottish trader and a Creek mother, who allied himself with the United States, distinguished himself in several battles, and was commissioned a brigadier general in the Army volunteers by Andrew Jackson.

On November 3, 1813, a force under General Coffee surrounded the Red Stick village of Tallushatchee and killed every warrior they could find, as well as some women and children. David Crockett claimed that “we shot them like dogs.”

A week later, Jackson led his army into a similar rout of the Red Sticks at Talladega. Although, during the winter, many of his men deserted because of enlistment disputes, Jackson fought the Red Sticks at Emuckfau (January 22, 1814) and Enitochopco (January 24, 1814), where he escaped a near-defeat.

Red Stick casualties from these battles totaled several hundred, but it would soon be far worse for them at a place they called Tohopeka, which the Americans referred to as Horseshoe Bend.

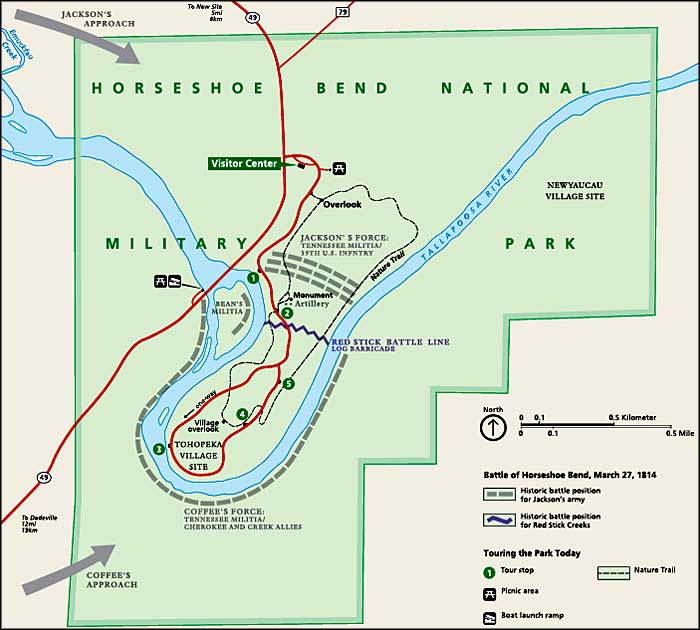

Slaughter at Horseshoe Bend

Late into the night of March 23, 1814, candles burned at the headquarters of Andrew Jackson’s Tennessee volunteers. The general dictated an order to be read to the troops before daybreak the next day, with the prospect of “avenging the cruelties committed upon our defenseless fellow citizens by the infuriated Creeks,” although, in fact, few atrocities had been committed on Tennessee soil by the Red Sticks. Nonetheless, Jackson continued, “our borders must no longer be disturbed by the war-hoop of the ruthless savage or the cries of the suffering victims.”

Harking back to Fort Mims, he exclaimed, “That torch which they lighted up on our frontier has blazed and must blaze again in the heart of their nation.” Having worked himself and presumably his soldiers to a fever pitch, Jackson enjoined them nevertheless to be merciful. He also warned, “Any officer or soldier who flies before the enemy without being compelled to do so by superior force and actual necessity shall suffer death.”

In the predawn twilight of March 25, 1814, Jackson’s troops each drew 24 rounds of ammunition and an eight-day supply of rations consisting of bacon, jerked beef, and “bread stuff.” At 5:00 a.m., the army melted into the dark and trackless wilderness leading to Tohopeka, 52 miles to the east. Holding back 450 men to garrison Fort Williams and a strong guard at Fort Strother, Jackson took the field with 3,200 soldiers and allied Indian warriors, giving him a solid three-to-one superiority in numbers over the Red Sticks.

With their barricade before them and the Tallapoosa River behind them, Chief Menawa’s warriors waited confidently. Women and the elderly tended to their daily tasks, children played, and dogs darted among the log cabins tucked in the horseshoe-shaped bend of the Tallapoosa River. Its waters were high and ran fast from recent rains. Canoes fringed the near bank. In the unlikely event that soldiers breasted the barricade, the canoes would provide a rapid means of escape for Creek noncombatants.

Few warriors, however, intended to abandon the place, no matter what the outcome. They intended to fight or die defending the Red Stick doctrine. That bold spirit characterizes Creeks to this day. “It is part of our ethos as a people that we see those Red Stick warriors taking a last stand,” explains a prominent tribal citizen. “That piece of information is handed down: We take the last stand. We call ourselves Este Maskoke Ispocogees: ‘the last people.’ We take ‘last stands’ and pull together in moments of extreme danger. And that is what they were doing at Horseshoe Bend — pulling together.”

Not that the Red Sticks saw a literal last stand in the offing. They had had seven months to prepare their defenses, time they put to excellent use, creating the most imposing Indian-built fortifications the American army would ever confront. A 350-yard-long wall of thick pine logs, stacked five or six high, and held in place with upright pine posts and props, zigzagged across the neck of the hundred-acre peninsula.

In some places, the breastworks rose to a height of eight feet; nowhere were they less than five feet high. Sharpened stakes protruded diagonally upward from ground level toward potential attackers. Clay chinking filled gaps between the logs. Two rows of firing ports were cut in the logs at regular intervals, permitting defenders to shoot standing or kneeling, while protected from return fire. To ensure that the attacking soldiers would be easy targets for their own fire, the Red Sticks cleared portions of the ground to their front.

Nothing in the armed hordes with which the Creeks had wrestled at previous battles suggested that white soldiers possessed the wherewithal required to storm breastworks. The Red Sticks could not know that their nemesis Andrew Jackson had assembled a real army, well-disciplined and determined to fight.

The Creeks also took comfort from the divine hand that lay gently over Tohopeka. Their tribal prophets, whose incantations grew louder as Jackson’s Tennesseans drew nearer, assured them that the village and its defenses rested on consecrated land that was impassable to white men.

Conferring with his confidant General Coffee, Jackson devised a simple but ingenious plan — theoretically, at least — to attack the Creek warriors, with the help of 500 Cherokee allies and William McIntosh’s hundred Lower Creeks, who opposed the militant Red Sticks. Coffee and his men were to ford the river three miles southwest of Tohopeka and throw a cordon around the far bank of the horseshoe-shaped bend to prevent escape. Jackson, meanwhile, would march directly against Tohopeka with the infantry and the artillery company, batter gaps in the breastworks with his two cannons, and launch a grand bayonet charge against the weakened defenses. The Red Stick peninsular refuge would become an inescapable trap.

Or so Jackson thought, until he saw the barricade stretched before him. “It is impossible to conceive a situation more eligible for defense than the one they had chosen, and the skill which they manifested in their breastwork was really astonishing,” he later told General Pinckney. “It extended across the point in such a direction that a force approaching would be exposed to a double fire, while they lay entirely safe.”

Jackson waved his two cannons forward to an open knoll a mere eighty yards from the nearest stretch of the breastworks to begin the task of splintering the Red Stick defenses. Along with the blue-coated Regulars and Tennessee Militias, Jackson mustered just under 2,000 fidgety infantrymen.

Behind their barricade, a thousand fiercely festooned warriors howled and mocked their opponents. In language colorful and obscene, English-speaking Red Sticks taunted the soldiers to attack. Most were painted for battle. The colors black and red predominated. Some warriors stripped to their breechcloths; others sported linen shirts. Nearly all wore leather leggings. Those lacking muskets clutched bows and arrows. The warriors also tucked war clubs and tomahawks in their belts for use, in the unlikely event that any soldiers lived long enough to scale the barricade.

The cannoneers trained their pieces on the center of the barricade. At 10:30 a.m., the guns boomed their smoky greeting. Their light-caliber balls bounced off the massive pine logs. Subsequent shots had no greater effect. Jackson seethed: “Such was the strength of the wall that it never shook.” A few of the small three-pound balls embedded themselves in the clay chinking between logs, but the two-gun barrage on the barricade “had no effect to demolish it or to drive the enemy from behind it,” confessed Colonel William Carroll.

The Creek warriors clearly had the upper hand. Eleven artillerymen crumpled around their cannons. On the forward slope of the high ground behind the barricade, in plain sight, three Creek prophets waved cow-tail banners, chanted and danced, delighted that the Master of Breath blew the force from the Tennesseans’ cannonballs before they had struck.

An hour passed, and then another. Old Hickory seemed to be out of ideas. Unwilling to risk a charge, he simply continued the cannonade.

General Coffee had had no trouble getting his men into position undetected by the Red Sticks before the artillery barrage began. His U-shaped line rested on a wooded bluff a quarter mile from the Tallapoosa. Unknown to the warriors who manned the barricade a mile to the north, or to the noncombatants who clung to their cabins during the cannonade, escape was now impossible.

The stalemate at the barricade annoyed the Cherokees as much as it did the Regulars. Unlike the soldiers, however, they had no intention of standing still. Watching the Creek women and children dart about their village, safeguarded by only a handful of fighting men, the Cherokee corporal Charles Reese and two other warriors swam the swollen, 120-foot-wide Tallapoosa and brought two canoes back across the river. Other Cherokee warriors piled into the two canoes and paddled to the far side of the river to engage the Red Sticks in the rear.

It was noon. Like Jackson, the Red Stick Chief Menawa faced a tactical dilemma. His warriors were holding their own against the Cherokees, but they needed help to retake the village and rescue the women, the children, and the elderly trapped behind Cherokee lines. Reluctantly, Menawa detached warriors from the barricade to meet the threat to his rear. Others, concerned for the safety of their families, broke away of their own accord.

Jackson finally realized that he had no alternative but to charge. The cannons had fired 70 rounds, to little effect, and eleven gunners lay wounded on the knoll. Cherokee audacity had attenuated Menawa’s front line. Further delay would gain Old Hickory nothing.

At 12:30 p.m., Jackson gave the necessary orders, and the 14-year-old drummer boy of the Thirty-Ninth Infantry beat the long roll. Officers barked out final commands, the men straightened their ranks, and then the blue-coated regiment surged forward. A West Tennessee militia company and a scout detachment squeezed into the front line to the left of the Regulars. Several companies of East Tennessee militiamen fell in on the right.

“Never were men more impatient for a charge than those by whom it was now to be made,” recalled Major John Reid. “The least deliberation must have convinced everyone that many must fall in the perilous undertaking, but no one deliberated. It was a moment of feeling and not of reflection.”

Agony and death awaited them at the barricade. Wherever they were able, soldiers thrust muskets through loopholes that emptied when Red Sticks withdrew their weapons to reload. Warriors, in turn, regained the apertures when the soldiers reloaded. Occasionally, soldiers and warriors wrestled their weapons through the same loophole. Rushing the breastworks on foot with his men, Major Lemuel Montgomery fired his pistol through a vacant loophole, killing an Indian. A return shot through the same opening wounded the major. Hoisting himself to the top of the barricade, he turned, waved his hat, and urged his men to scale the works. A musket ball crashed into Montgomery’s skull, cutting short a promising life.

Private James Love crossed the barricade first. As he leaped to the ground on the Red Stick side, a hurled tomahawk caught him in the chest and split apart his ribs. He survived, but bore a huge scar for the rest of his life.

The fight was bitter, but brief. Cheering Regulars rapidly punched gaps in the sagging Red Stick ranks. On the extreme right of the regimental line, Ensign Sam Houston climbed the barricade with his platoon. He slashed at Red Sticks with his sword until a barbed arrow buried itself in his right groin. Hobbling about exhorting his men, Houston kept on his feet until the warriors retreated to a log-roofed redoubt beside the riverbank. Then, bleeding and helpless, he sank to the ground.

No one attended to Chief Menawa. He lay unconscious amid a heap of slain warriors. Six musket balls had perforated his body. When he recovered, the leader found himself weltering in blood, his hands clutched firmly about his musket. The battle had swept past, but continuing shots and rippling volleys told him that the killing was far from over. Rising slowly to a seated posture, he saw a soldier pass nearby. With deliberate aim, the man fired. A ball plowed through Menawa’s mouth from cheek to cheek, carrying away several teeth. He slumped back amid the dead.

After the collapse of the barricade, the Battle of Horseshoe Bend degenerated into a five-hour slaughter that ended only with nightfall. Despite Jackson’s general orders before the battle in which he called for restraint, atrocities and needless deaths abounded.

Separated from his parents, a small Creek boy ran about the village bewildered until a soldier crushed his ’skull with the butt of his musket. An officer upbraided the man for his barbarity. “Oh, it is all the same,” replied the murderer. “He will make an Indian someday.”

The old died with the young. A wizened man whom one scout guessed to be at least 90 sat on the ground in the village, busily pounding corn in a mortar, apparently oblivious to the carnage and the crackling of burning cabins. Most of the scouts ignored the harmless and perhaps dementia-plagued man, but a soldier killed him in cold blood. He did so, he told his disgusted companions, “so that he might tell his people at home that he had killed an Indian.”

When it became apparent that the battle was lost to them, few Red Stick warriors bothered to fight on. Notwithstanding their pledge to make a last stand at Tohopeka, most were reluctant to die needlessly. Unaware that Coffee’s riflemen lined the timbered far bank, nearly 300 warriors leaped into the Tallapoosa, hoping to swim to safety. Some shoved logs into the water, to which they clutched while crossing.

Those who took to the river never had a chance. Rifle shots hit the heads of swimmers. Those clinging to logs “would drop like turtles into the water,” a rifleman recalled. Several corpses came to rest against the riverbank; others vanished beneath the water. Many more floated downriver. No more than 30 warriors escaped the battlefield, most of whom waited until nightfall to swim the river. By then, concluded one of General Coffee’s troops, “the Tallapoosa might be truly called a river of blood, for the water was so stained.”

Warriors who chose to honor their pledge to make a last stand on the peninsula fought and died until just two apparent clusters remained: the Red Sticks who had taken refuge in the log-roofed redoubt in the ravine near where Sam Houston had been wounded, and a second cohort that clung to the riverbank beneath an overhanging bluff.

General Jackson tried to halt the carnage. Dismounting and sheltering himself behind a large oak tree, he told a Muscogee-speaking scout to call on those in the redoubt to surrender. They replied with musket shots. A ball glanced off the tree near Jackson’s’ head and struck the scout in the shoulder. That ended Jackson’s peace overture, and the slaughter of Red Stick remnants continued deep into the night.

Jackson would eventually break the back of the Red Stick resistance at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. At least 850 Red Stick warriors died defending their families and way of life against Jackson’s army, a Native death count never exceeded in the two centuries of conflict between American Indians and the expanding American republic.

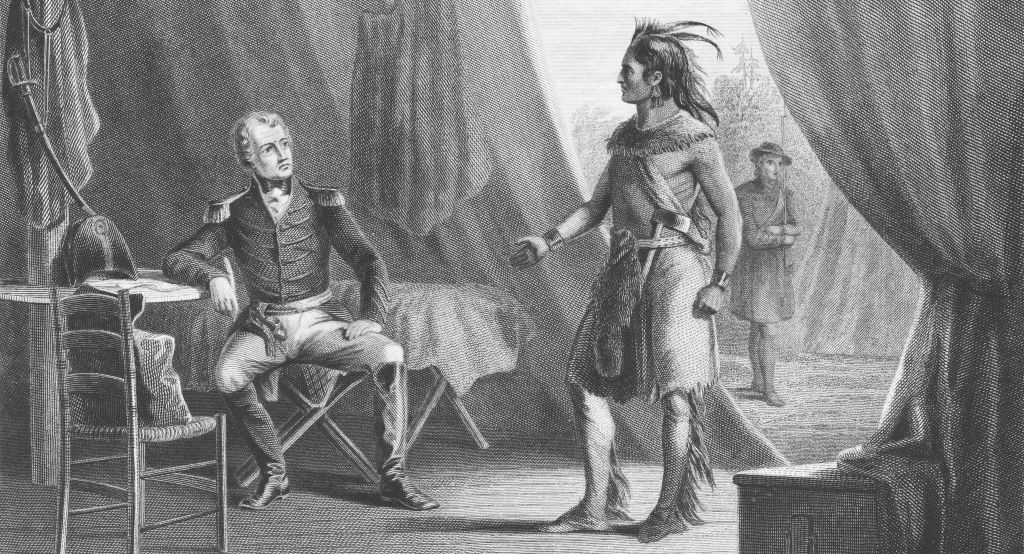

The Creek War thrust Andrew Jackson into national prominence. He began the conflict as a general in the Tennessee militia whose political star seemed on the wane. His’ victory over the Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, the climactic action of the Creek War, won him a major general’s commission in the Regular army and command of the vast military district that embraced New Orleans.

Without the Creek War, Jackson would never have had the opportunity to beat the British at the Battle of New Orleans and become the most celebrated general to emerge from the War of 1812. But did he really deserve the accolades and the promotion that came after Horseshoe Bend? Before that battle, his combat performance against the Red Sticks had been mixed, at best. At Horseshoe Bend, it was not Jackson but, rather, his Cherokee and friendly Creek scouts acting on their own initiative — the very men he would later expel on the Trail of Tears — who won the battle for him.

Jackson commanded only some of the militia that invaded the Creek nation during the war. But he alone possessed the will to see the conflict through.

While commanders from Georgia, the Mississippi Territory, and eastern Tennessee abbreviated their campaigns because of chronic supply shortages, enlistment problems, Red Stick resilience, and the relative indifference of a U.S. government locked in war with Great Britain, Jackson persevered.

Enfeebled by a festering gunshot wound and severe, chronic diarrhea, and plagued by inconstant superiors, Jackson demonstrated fortitude and courage rarely witnessed in American military annals. He brooked no dissent, treating his own sometimes-recalcitrant troops with a harshness that astonished the militiamen and volunteers. Jackson displayed unbridled ambition, an outsized sense of honor and duty, and periodic cruelty that were extreme, even in the context of his times.

Andrew Jackson and his fellow expansionists reckoned the cost of the fighting relatively small. In appropriating the Indian lands of the Southeast, however, the young republic inadvertently sowed the seeds of the American Civil War. The conquest of the Creek country reinvigorated a faltering slave-based cotton economy by injecting it with highly fertile soil on which to prosper under white plantation owners. The few score slaves of dispossessed wealthy Creeks and Métis had produced comparatively little in times past. But, by 1860, one of the two highest concentrations of cotton production in the antebellum South was on former Creek land.

Brutality in the Deep South did not end with the Creek War and the Trail of Tears. It was simply replaced by the horrors of what white Southerners euphemistically called the “peculiar institution.”